There's a sharp and hilarious little scene about halfway through Pietro Germi's 1964 comedy Seduced and Abandoned. The chief of police in a small Sicilian town turns from his office window to a map of Italy on the wall. He stares at it for a second, then covers the island of Sicily with his hand. He does this a few times, nodding with approval every time his hand deletes Sicily from Italy.

I can guarantee you that an Italian audience, whether in Palermo, Rome, Venice, Genoa or Milan, would have burst into helpless laughter at this bit of business.

Well, maybe not in Palermo. And definitely not in 1964.

Seduced and Abandoned is an Italian film, though an Italian would tell you that it's a Sicilian film, as there was no other place in all of Italy where every outlandish plot twist could plausibly occur in rapid succession. And as a comedy it delivers plenty of laughs (though you'd have to be Italian, and even more of a certain generation to get them all), but as it draws to a close it reveals a spine of steel, and a cruelty shared by the best satire, then or now.

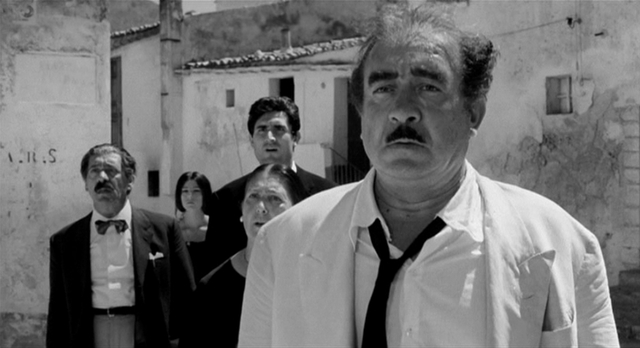

The film begins in the middle of a hot Sunday afternoon in the household of Don Vincenzo Ascalone (Saro Urzi) and his family. Everyone has succumbed to the torpor of a typical afternoon and doze fitfully, sweating in their beds. Everyone except Peppino Califano (Aldo Puglisi), the fiancé of Matilda Ascalone (Paola Biggio), and Agnese Ascalone (Stefania Sandrelli), Matilda's sister and the beauty of the family (though her mother thinks she's too skinny).

With his two-tone shoes and little moustache, Peppino is your classic spoiled Italian son, accustomed to getting what he wants – and what he wants on this torrid afternoon is Agnese. Nursing a crush on her sister's fiancé, Agnese allows him to seduce her amidst the laundry hanging in the courtyard balcony, as Peppino presses himself on the girl muttering "What are you making me do?"

In the aftermath of what's basically statutory rape – Agnese is just on the wrong side of sixteen – the two are painfully awkward with each other; Peppino begins avoiding the Ascalone home and Agnese stops eating, devoting herself to prayer every minute of the day, sleeping with rocks under her bedsheets as penance.

But this is the kind of secret that can't be covered up, especially as Agnese is pregnant, and the rest of Germi's film is devoted to the increasingly desperate efforts of Don Vincenzo to make Peppino pay for his actions and salvage his family's honour. Because honour and family are the targets of Germi's comedy, and specifically how they obsess the inhabitants of small Sicilian towns where Vespas and Fiats share the dusty streets with horse carts.

Pietro Germi was a Genoese actor who began writing and directing films after World War Two, making a string of dramas and crime pictures until he had a huge and unexpected success with Divorce Italian Style in 1961. A black comedy like Seduced and Abandoned, it starred Marcello Mastroianni as a Sicilian nobleman living in reduced circumstances (like so many of his class), who falls in love with his 16-year-old cousin (also played by Sandrelli).

Since divorce was illegal in Italy, his only way out of his marriage is an "Italian style" divorce – killing his wife in the throes of passion. Murder in cold blood would mean a life sentence, whereas an honour killing in a fit of rage invited a nominal sentence under both Italian law and Sicilian custom.

His mostly inept attempts to engineer both an affair for his wife and a plausible opportunity for her murder are told with the same fantasy sequences and cascade of unintended consequences that Fermi would rely on for Seduced and Abandoned. The films – along with the subsequent 1966 film Signore & Signori (titled The Birds, the Bees and the Italians in English) – would comprise an informal "honour trilogy" and shift the rest of Germi's career to comedies.

There's no fondness in Germi's portrait of Sicily and Sicilians; the exasperated police chief – a Northerner for whom rural Sicily is a hardship post, played by Oreste Palella – is a stand-in for the director, along with the town's judge (Attilio Martella). The latter tries vainly to impose some rule of law, while the policeman is wiser, escaping to the countryside with his junior constable to lie under a tree when he realizes what kind of legal farce the families of Don Vincenzo and Peppino are poised to set in motion on the feast day of the town's patron saint.

"Sicily is ungovernable," wrote Luigi Barzini, author of The Italians. "The inhabitants long ago learned to distrust and neutralize all written laws." The characters in Germi's story will appeal to the law, but at no point will they act as if their lives are bound by it – or by truth. Or as the police chief declares when trying to take down a legal deposition: "This is Sicily! No could mean yes!"

Upon discovering the truth, Don Vincenzo forces Peppino to break his engagement to Matilda, and sets about replacing him as her fiancé with Baron Zappalà (Leopoldo Trieste), who we first meet trying to hang himself in a vast empty bedroom of his crumbling palace.

Zappalà could be the descendent of Don Fabrizio, the Sicilian aristocrat played by Burt Lancaster in Lucino Visconti's The Leopard, released just a year earlier. His father once had enough money to loan Don Vincenzo the money needed to buy the quarry that's made him part of the town's elite, but the debts he left Zappalà forced him to sell his portrait along with the rest of his patrimony and rent out the rooms in his family palace.

It's easy to imagine that the oversized antique furniture that fills the Ascalone's home might once have belonged to the Baron, and part of the bargain Don Vincenzo strikes with him is for new teeth to replace the ones he's conspicuously missing. He gets the aristocrat as a potential son-in-law for a bargain – basically dentures and a few home-cooked meals.

Which leaves the problem of Agnese and Peppino, which Don Vincenzo sets about solving with selective application of the law. Vincenzo frequently invokes a family connection when trying to get around bureaucracy or waiting lists – his cousin, a lawyer for some judge's brother. After bribing the local undertaker – the town's fixer and middleman – to find out where Peppino is hiding, this cousin (Umberto Spadaro) advises him to send his dimwitted son Antonio (Lando Buzzanca) to shoot Peppino; a crime of passion done to save family honour will get the customary nominal sentence.

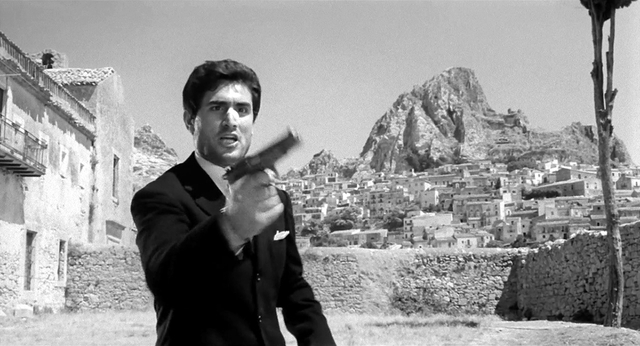

Germi spoofs Sergio Leone's showdowns and even the music of Ennio Morricone in the subsequent scene: Antonio walks past silent locals through a sun-baked town square to the monastery where Peppino is holed up, assisting his uncle, a priest, while he says mass - despite the young man admitting he's an atheist in an earlier scene. (What's really remarkable is that Leone's A Fistful of Dollars wouldn't come out until two months after Seduced and Abandoned. I have yet to read an explanation of Germi's prescient cinematic satire.)

But Don Vincenzo's plan goes off the rails when Antonio throws his gun at the fleeing Peppino instead of shooting him, just as the police chief and his constable show up to arrest them, sent by Agnese. This escalates the situation in the eyes of the law, and Don Vincenzo is forced to create an even more elaborate farce.

The sweating, bellowing patriarch is the protagonist of Germi's story, a clever man cursed with halfwit children. (Don Vincenzo is apparently unable to recognize the flashes of intelligence that Agnese shows; like all of his daughters she's just a problem meant to be solved with marriage.)

After the success of Divorce Italian Style, Germi was under some pressure to cast a big-name foreign actor as the lead and, like Lancaster in The Leopard, dub his dialogue in Italian. He apparently considered Earnest Borgnine, Rod Steiger and even Jean Gabin for Don Vincenzo, but chose Urzi – a wise decision confirmed when Urzi won the award for Best Actor at Cannes that year.

(Germi would later cast Dustin Hoffman opposite Sandrelli in Alfredo, Alfredo (1972), his last film – a comedy about a timid bank clerk trying to divorce his domineering wife. As was the custom with Italian cinema at the time, not just Hoffman but Sandrelli had their dialogue dubbed.)

Don Vincenzo is advised by his lawyer cousin that Peppino's rape of Agnese will be nullified if he kidnaps the girl and gets her to agree to marry him: the marriage apparently making the rape and kidnapping disappear in the eyes of the law. This is laid out by Article 544 of the civil code – a legal statute so revered in Sicily that one character says children learn it along with their catechism.

After a Fellini-esque nightmare where Agnese enters a courtroom alongside the town whores and is forced to marry Peppino in front of a jeering, grotesque gallery of citizens and convicts, Don Vincenzo puts his master plan into action. He stage manages Peppino's parents as they plead for their son's liberty, loudly playacting his outrage at their affrontery in front of the whole town. He even arranges for Peppino to serenade his house at night, theatrically driving the young suitor off with a shotgun blast.

This is the set-up for the final bit of theatre: Peppino's abduction of Agnese. By this point, however, the girl no longer wants her seducer, though poor bovine Matilda has convinced herself that Peppino's serenade was actually for her and has to be sent away to visit relatives with her grandfather.

And Peppino no longer wants Agnese; he insists that it's his right to marry a virgin, despite being the one that took her virtue. But their wants and desires have to be sacrificed for family and honour, and the abduction is scheduled to take place in front of the whole town during the festival of its patron saint.

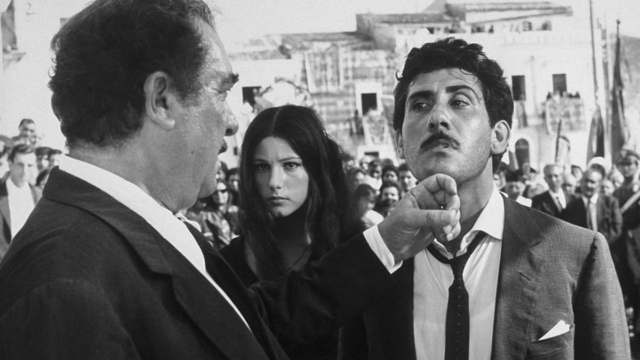

In Italian Cinema from Neorealism to the Present, Peter Bondanella writes that Germi "manages to recreate the oppressive atmosphere of the small Sicilian village" as his camera moves "through endless groups of staring, leering townspeople. Peer pressure, voyeurism, and repressed sexuality seem to constitute the basis of Germi's vision of Sicily: men aspire to seduce the women of the town, yet ridicule their friends who become cuckolds; people incessantly watch each other through windows or doors, from balconies and opera boxes, and in the streets; fathers subject their daughters to humiliating physical examinations by midwives to certify their purity..."

As Don Vincenzo's wife and their daughters walk to the town square in a line, dressed in black, the patriarch watches nervously from the door of a café. Agnese is one of the few people unaware of what's about to happen; the police chief and his constable have already escaped to the countryside, intent on taking no part in the ensuing legal farce.

Things start going wrong when Peppino's "accomplices" chase down the wrong sister. Outside the town after making their "escape" the prospective husband and wife are unable to hide their contempt for each other, but they turn around and play their parts nonetheless, driving back through the church procession to make a show of asking for Don Vincenzo's blessing. They invite their friends for a celebration and take their place on their balcony to watch the church procession.

But things go wrong the next day when everyone – the now-betrothed couple, their families, their lawyers and the town priest – all appear before the magistrate to get the charges against Peppino dropped. Agnese is unable to continue with the farce; she bites her fiancé's hand and the judge charges Peppino with not just rape but kidnapping.

This breaks the spell their performance had on the townspeople, who criticize the whole sorry show with a barrage of wild gossip: Peppino is impotent; Agnese is a whore, as are all of her sisters. This is too much for the Baron, who suddenly decides his family reputation isn't worth the price of a new set of teeth.

Agnese has a nervous breakdown after being chased through the streets by a crowd of young men; her father collapses and ends the film on his deathbed, unable to attend the inevitable but dismal wedding of his daughter; the Baron tries and fails to hang himself; poor Matilda has to enter a convent. The film ends with the camera panning in on Don Vincenzo's bust in the town cemetery, emblazoned with the words "Onore e Famiglia". In the end Germi makes us pay for every laugh in the picture.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.