There's a movie out now that imagines modern America in the grips of a civil war. It is, as far as I can tell, a wholly logic-free bit of fantasy (California and Texas uniting as a rebel front!), with a script that hits its ideological touchstones like a piledriver. It's an election year, so expect more of the same, but it's worth comparing this First World fever dream of social collapse with a story grounded in a very real, recent, historical moment.

The Dancer Upstairs (2002) begins with four people driving at night along a country road. They're listening to Nina Simone – a recording of a concert where Simone is taking a (customarily) long time to introduce a song. One of them complains, but the man in glasses in the passenger seat says that she's getting ready to sing. A lone policeman steps out into the road to flag them, but the woman behind the wheel coldly swerves and guns the car, running him over. His flashlight is caught in a car's wheel, its light and sparks from the road flashing as they drive around a curve, away from the body on the ground.

The next scene begins on another country road in the middle of a misty, overcast morning. Titles over the picture tell us that we're in "Latin America", and that it's "The Recent Past". A truck with the same four people pulls up to another checkpoint, choosing to stop this time. Rejas (Javier Bardem), a police sergeant, asks for their papers and notes that the man in the glasses has only temporary I.D. with no picture. He invites him into their little barracks and office where they chat while Rejas fills out new paperwork for him.

The man says he's a labourer but he doesn't look like one. While they chat the woman who we'd seen driving in the previous scene gives a bribe to Rejas' colleague. The man asks Rejas if his colleague has always been corrupt; Rejas smiles to himself and says that he can't speak for always, but certainly for the three years he's worked with him, and in any case this is his last day: he's been promoted. Rejas takes a Polaroid of the man in front of a distant, snow-capped mountain range, but while he waits for the photo to develop the group jump back in their truck and speed away.

The Dancer Upstairs is the only feature film (so far) directed by the actor John Malkovich. It's based on a novel by British writer Nicholas Shakespeare, whose father had been ambassador to Peru in the mid-'80s. It might be set in an unnamed South American country, but the details place the story firmly in Peru in the '80s and early '90s, when the Sendero Luminoso or Shining Path, a Maoist guerilla movement, began bringing its terror campaign from the countryside into the capital city, Lima.

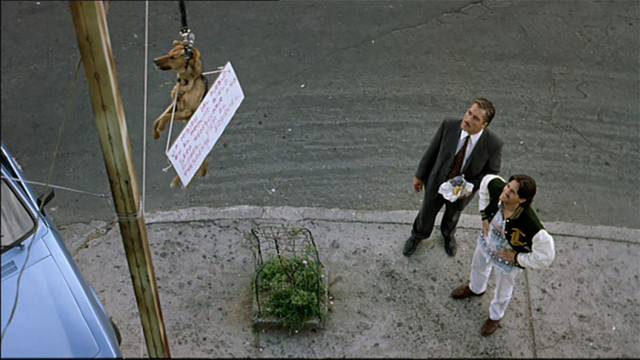

After a five year break the story rejoins Lt. Rejas in "the capital", where he's assigned to security details protecting diplomats. He and his partner Sucre (Juan Diego Botto) come across a dead dog hanging from a telephone pole, a stick of dynamite stuck in its throat and a sign around its neck saluting "President Ezequiel". Rejas inquires if there's any information on Ezequiel, just before the city is suddenly full of dead dogs hanging from poles, decorated with signs quoting obscure passages from philosophy and the Bible and Ezequiel's name.

Rejas comes from humble origins, of mixed race in a country where Quechua-speaking natives are at the bottom of the social ladder. His father had been a coffee farmer until the military confiscated his land during a coup. He became a lawyer with a prestigious firm and defended a young woman who was raped by the country's current president – a case that was dropped when her family was threatened and she fled to Miami. Disillusioned, he left the law and joined the police, paying his dues by being stationed in a remote checkpoint.

Worried that the government will step in and reverse the fragile progress the country's made toward democracy, his boss assigns him and a small team to find out what they can about Ezequiel. They determine that years' worth of unexplained bombings and assassinations all over the countryside, attributed to student radicals and cartels, were the work of Ezequiel's group, who have now moved their campaign into the capital.

The Shining Path, led by the shadowy Chairman Gonzalo, reached the zenith of its terrorist campaign at the turn of the '90s, giving Peru a top spot among the unstable regimes of South and Central America, after Argentina, Chile, Guatemala, Nicaragua and El Salvador had held marquee positions, and before Colombia, Brazil, Argentina (again!) and Venezuela took over the headlines.

When Gonzalo was captured in 1992, in an apartment over a Lima ballet studio, he was revealed to be Abimael Guzman, an obscure and rather mediocre former professor of philosophy who had gone into hiding in the '70s, forming his Maoist guerilla group in the remote countryside of Peru, where he had hoped to build support among the indigenous population.

The victims of his group's terrorist campaigns were mostly the same Quechua-speaking natives, casualties of the Shining Path's reckless use of bombs – tied to donkeys and dogs and even chickens let loose in markets, or carried by children into hotels and government buildings. In a country like Peru where mining is a major industry, dynamite is far easier to acquire than guns.

Like Ezequiel in Malkovich's movie, Gonzalo issued no manifesto, made no demands nor put forward any spokesperson, and the group's victims were lost in the body count created in competition with rivals such as the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Group – just more bodies in some remote village or town, easily overlooked as the country attempted to rebuild after the latest military regime.

Malkovich became interested in the story of Guzman and Peru when he read Nicholas Shakespeare's "In Pursuit of Guzman" in a 1988 issue of Granta, in which the writer admitted his obsession with Shining Path, the inspiration for The Dancer Upstairs when it was published in 1995. The actor secured the rights and asked Shakespeare to work on the screenplay with him, but this was only the start of the film's long journey to the screen.

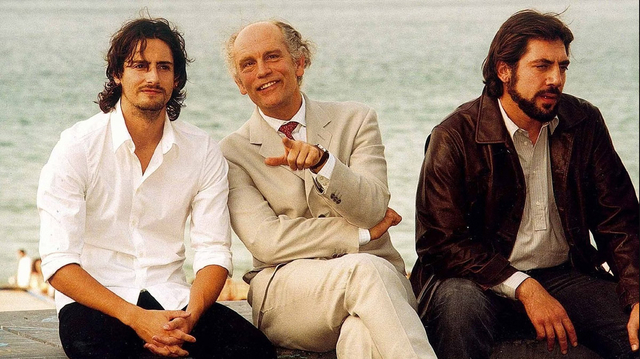

Bardem was originally his choice to play Sucre, and the early backers of the film insisted on a big name for Rejas, which was originally offered to Daniel Day Lewis. By the time it looked like the film was going to get made Bardem's English had improved and he had aged into the role of Rejas, but it was still three years between completing the picture and seeing it released and it might have languished in some vault if Bardem hadn't got an Oscar nomination for Before Night Falls.

By the time he was doing interviews to publicize the film, Malkovich talked as if he had nearly forgotten about The Dancer Upstairs, telling the Detroit Metro-Times that "it could come out and be forgotten five minutes later. I never worry about something I can't control," adding that "I think also it'll be a film that causes people to reflect and question rather than answer."

"Most films are things that answer," Malkovich said. "I don't have any answers."

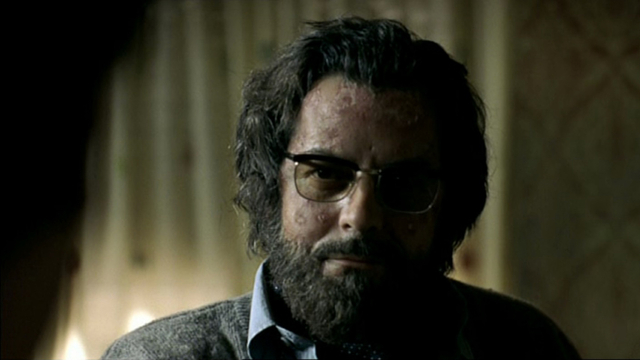

The big question asked both by Shakespeare and Malkovich's film is how someone like Guzman could bring a country to the edge of collapse. In "Guzman Found", an article he wrote a year after Guzman's arrest, Shakespeare echoes the chorus of people astounded at how unremarkable the man who described himself as the "Fourth Sword of World Communism" turned out to be when police videotaped him during his capture.

Guzman looked like "little more than a mollycoddled theorist who crumbled as soon as he entered the air." Talking with Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa, Shakespeare asked "How can he collapse like that after preparing a revolution so methodically for almost thirty years?"

"Because he's a Peruvian intellectual," Vargas Llosa answers.

The police found two videotapes during their long search for Guzman, one of which is recreated for Malkovich's film. Shakespeare describes the man in one video as "a grub-fat, grey-bearded man in thick spectacles." In the other he's dancing like Zorba the Greek at a party "stomping on a floor strewn with flower petals and applauded by followers with moony-eyed faces as if gazing at a political baghwan. Again he appears to be insensible with drink."

Or as Sucre mutters to himself after the police lead Ezequiel away, he was "just a fat man in a cardigan."

Shakespeare based the character of Rejas on two men: Col. Benedicto Jiminez, who led the raid that captured Guzman, and Gen. Antonio Vidal, who led the search for Guzman for twelve years. But he added a love interest to the story – Yolanda (Italian actress Laura Morante), based on Maritza Lecca, the dancer who sheltered Guzman in the apartment above her Lima dance studio.

In the book and the movie, Yolanda is teaching dance to Rejas' daughter, and the beginning of an affair grows between them during the film. Rejas' wife is a beautiful woman who's saving up for a nose job; we see her nervously deliver a presentation about a trash romance novel to her book club and get involved with a cosmetics multilevel marketing scheme. She doesn't seem to have much in common with her reserved, intellectual husband, and we're led to presume that she thought she was marrying a lawyer and not a cop who's constantly worried that his paycheque will bounce.

Yolanda on the other hand is sensitive and artistic, able to talk about ideas with Rejas, who makes a point never to let her know what he does for a living. Hints are dropped throughout the picture teasing Yolanda's secret, like the Nina Simone she plays in her studio while choreographing a dance routine, but Malkovich is skillful enough to soft pedal them for viewers who might not know about Guzman and Lecca.

Shakespeare notes that Guzman's inner circle was full of women devoted to him with a religious zeal, and that many were ex-nuns or from devoutly Catholic backgrounds. It's a dynamic that plays out in a startling number of radical political groups whose most ardent followers resemble a cult. Guzman's followers "loved him as they had loved God, innocently, without the slightest doubt," Shakespeare writes.

He admits that he's obsessed with Maritza Lecca, who lived a double life without any of her friends and family suspecting that she was involved in a terrorist group, and not just as one of Guzman's enablers: she's presumed to have organized a bombing in Lima's Miraflores district at the height of Shining Path's terror campaign that killed eighteen people.

On the night of Guzman's capture her uncle, a famous Peruvian composer named Celso Garrida Lecca (Shakespeare describes him as a "fashionable Marxist") and his lover, dancer Patricia Awapara, decide to pay a surprise visit on Maritza, who was supposed to be performing as Antigone in a ballet written by Celso and choreographed by Patricia but had been missing rehearsals.

They end up getting caught up in the police raid and spend the night lying face down on the floor of Maritza's studio. When the police take off their masks Celso is shocked to find himself next to Peru's most wanted man. Even more disturbing are the wild-eyed women standing around Guzman punching the air with their fists and screaming "Viva Abimael!" at the police. One of them is his niece, her face "contorted with rage."

The best part of Malkovich's film is his depiction of a city threatened with revolution. Civic order is fragile and the government is apparently better at corruption than paying the wages of employees like Rejas. There are two shocking, bloody scenes that show the sharpest edge of the terrorist war on the regime.

A government minister and his wife are assassinated onstage at a pointedly pretentious performance art event, and an admiral and his staff are gunned down by a group of schoolgirls in kilts and white knee socks. This brings down the heavy hand of the government in the form of the sinister Calderon (Portuguese actor Luis Miguel Cintra), a character based on the outlandishly named Vladimiro Lenin Ilich Montesinos Torres, head of Peru's National Intelligence Service under president Alberto Fujimori.

He puts the army in charge of the hunt for Ezequiel, who proceed to declare martial law and curfews. It also brings the sort of brutal excesses Rejas and his boss feared, when a group of students rehearsing a play are abducted and disappeared. (In real life it was nine students taken from their residence and never seen again.)

There's a comic moment when Rejas' sexy blonde landlady flirts with him, begging him to tell her if there's going to be a revolution so she'll know what to wear. We hear car bombs going off all over the city, and fireworks burst in the sky during frequent blackouts. The rebels dot the sides of roads and the waterfront with flaming hammer-and-sickles. It feels like the country is being invaded from within, but the most chilling part of the picture painted by Malkovich and Shakespeare is that the enemy could be anyone, even your closest friends and relatives.

There's a nail-biting moment before the raid to capture Ezequiel when Rejas sees that his daughter is still waiting to be picked up after a lesson at Yolanda's studio, but his wife arrives late, chats with Yolanda, applies her lipstick in the rear-view mirror and begins singing along with the car radio, sending the policeman into an uncharacteristic rage.

He's still unable to imagine Yolanda's role until just after Ezequiel's capture; when she realizes his part in it all she beats him with her fists, spits at Rejas and screams "Viva President Ezequiel!" before being led away. After her trial, and the heavy sentence pronounced by a military tribunal, Rejas uses his new popularity with the public to negotiate more lenient conditions for her in jail, including books, writing utensils, blankets and a light in her cell.

Calderon extracts a heavy price from Rejas, but then admits that she already had access to pens and paper before handing him a letter from her. Shakespeare bases it on the one Maritza wrote to her mother after she tried to visit her in prison: "I am already dead," it reads. "I live only for the revolution."

I went to Peru in 2003, just after seeing Malkovich's film, as a guest of PROMPEX (now PromPeru), the government's trade and tourism commission. I was there to cover a mining trade show in Lima, which I found charming despite Shakespeare's description of it as "vile" and "this cancer of a city." I visited Cusco and Machu Picchu, discovered chifa (the country's blend of Chinese and creole cuisine), Inca Kola and pisco sours.

But it was hard to ignore the lingering shadow of Shining Path, by now reduced to a few hundred rebels holed up in the distant mountains of the country. The government of Alejandro Toledo was doing its best to let the world know that Guzman and the corruption that brought down Fujimori's government were firmly in the past, but I wasn't sure if anybody believed it.

Like most visitors from the Anglosphere I was brought up short by the sudden but frequent appearance of men in body armour carrying automatic weapons on wide city streets, and by the houses in well-to-do Miraflores, each one a little compound complete with motorized gate, its walls topped with razor wire or shards of broken glass.

Juan José, my patient host and minder from PROMPEX said that he'd heard about Shakespeare's novel but not the movie. We were in a car being driven around the wide road circling the Plaza Dos de Mayo in Lima as he said this, when I saw a street vendor approach the car, his inventory displayed on a big piece of cardboard; his specialty was DVDs and right in the middle of the board was a brand-new bootleg copy of The Dancer Upstairs.

In a documentary included as a bonus feature with the DVD of the movie, Malkovich says that he considers it "intellectually corrupt" to support terrorism, and that he thinks that the apparently intelligent people who do so "should read more – and not newspapers."

So it's chilling how casually people glibly state that revolutionary change is necessarily "born in blood," like the university professor talking to his students in a café, just before he's brought in for questioning by Rejas' men. They're just words until he's persuaded to recall the undistinguished but radical man he shared a faculty post with at a provincial university years earlier. Later we're told that the professor has disappeared – presumably to a safe place like Miami, but perhaps not.

We see how easily children are turned into Ezequiel's soldiers, and how his followers include a model and dancers like Yolanda. The abundance of women at the heart of groups like Shining Path is a fact that impresses Shakespeare. (Coincidentally several recent studies found that there's a growing political gulf between men and women in Generation Z, notably in countries like South Korea, China, Germany and the U.K., with women becoming more radical while men become more conservative.)

Malkovich ends the film with an uneasy note. Rejas rushes to his daughter's dance recital after meeting with Calderon, arriving to watch her – the only girl onstage dressed in red – perform the choreography we saw Yolanda work on earlier in the film, to Nina Simone singing "Who Knows Where the Time Goes."

The camera rests on Bardem's face as he gazes at his daughter with adoration, but as we watch an undeniable anxiety starts to register. You have to recall the words spoken by Ezequiel as he's being arrested by Rejas – a line echoing Guzman on the night of his arrest. He taps his forehead, expecting the policeman to execute him on the spot, but when he's told that isn't going to happen he keeps tapping, saying that "It doesn't matter if you shoot us – we live in history."

Or as Guzman himself told Antonio Vidal at the end of a terrorist campaign that left 26,785 people dead, "You can kill me, but this will live on."

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.