The marvel of Katharine Hepburn's enduring stardom is how secure it is now, two decades after her death and three after her last film performance – especially compared to her early years in Hollywood, when audiences were having a hard time figuring out if they liked her at all.

From her first role in George Cukor's A Bill of Divorcement (1932), Hepburn's appeal with the moviegoing public had a one step forward, two steps back momentum. She'd go from a hit like Alice Adams (1935) to a string of flops like Sylvia Scarlett (1935), Mary of Scotland (1936) and Quality Street (1937).

It was at this point that she took a role in Stage Door, the 1937 comic drama where director Gregory La Cava laid out how it was possible for democratic America to sympathize with the blue-blood Hepburn and her essentially privileged characters. Her Terry Randall, the slumming debutante trying to get a break on the Broadway stage, needed to go over big before it was possible for her to secure her status with roles in Bringing Up Baby and Holiday (both 1938), The Philadelphia Story (1940) and Woman of the Year (1942), and beyond that to Adam's Rib (1949), The African Queen (1951), Pat and Mike (1952) and Desk Set (1957), by which point the Hepburn persona had become beloved and not just tolerated.

The film begins at the Footlights Club, a theatrical boarding house for women on the fringe of Manhattan's theatre district, where the simmering background hum of wise cracks and cattiness is suddenly broken by a fight between Linda (Gail Patrick) and Jean (Ginger Rogers) over a pair of stockings. They're roommates, but the hose that Linda has "borrowed" from Jean for her date with her sugar daddy, Broadway producer Anthony Powell (Adolphe Menjou), forces Linda to relocate to another room after Jean emerges triumphant from their fracas.

This is when Hepburn's Randall makes her entrance; she inquires about lodging and ends up taking Linda's place, bringing with her three massive trunks and as much class baggage. Even before they're made to share a room, Jean and Terry verbally spar with each other, Rogers mocking Hepburn's arch mid-Atlantic accent – the American version of what Britons knew as Received Pronunciation.

The two women spar verbally, sizing each other up and making quick decisions about what they're seeing. "I see in addition to your other charms you have that insolence generated by an inferior upbringing," Terry tells her new roommate. "I use the right knife and fork, I hope you don't mind."

"All you need is the knife," Jean retorts.

Cattiness is abundant in the banter between the women staying at the Footlights Club, but none of them act like they have an edge in privilege. Even Linda, with her gowns and furs and dinners out with Powell, knows that she'll be back to sharing lamb stew at dinner with the other girls sooner or later. But Terry represents another class, an interloper in a place full of women like Jean and Judy (Lucille Ball) who pay the price of crushed feet and boredom for a free meal and drinks with bumpkins visiting the big city. (Jack Carson appears briefly as Mr. Millbank, a lumberman from Judy's Seattle hometown who shakes Jean's hand like he's pumping water from a well.)

Class is at the heart of the conflict between Terry and Jean, and it's their resolution of this conflict – really the whole dramatic arc of the movie – that's ultimately the gift Rogers gives to Hepburn in Stage Door. Hepburn's Terry is more than a bit insufferable; taking in the room she'll be sharing with Jean, with its shabby old furniture and windows that look out over massive blinking marquee letters, she delivers a line in that impeccably Hepburn manner: "I've always longed to live in an atmosphere like this!"

What's unspoken is that even if many of the other girls had come from atmospheres much worse, they probably never longed to live anywhere like the Footlights Club, which is more a purgatory than a destination.

Writing about Hepburn's dilemma when she made Stage Door in The Runaway Bride: Hollywood Romantic Comedy of the 1930s, Elizabeth Kendall speculates that to RKO, "her puzzled studio, Hepburn must have seemed like an aging elder daughter, too old-fashioned for the suitors at the box office."

In the middle of the Depression her patrician persona was out of place and could have ultimately been fatal to her career. All the flops she got cast in show that RKO didn't know how to give this haughty child of wealthy progressive parents the common touch. Rogers, on the other hand, was "perhaps the most natural female democrat working in Hollywood in the thirties," according to Kendall. Putting them together as twin heroines in a story that didn't end with either of them married was a brilliant move by RKO producer Pandro Berman.

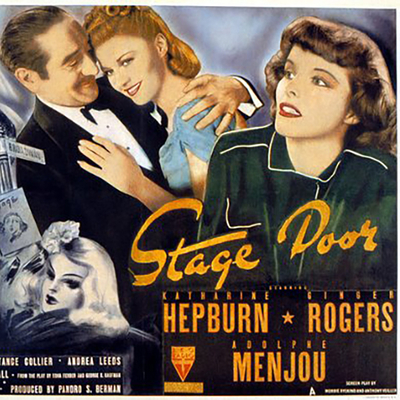

But if you never saw the posters advertising Stage Door, you might have a hard time picking out the heroines during the first ten minutes of the film. Because La Cava and screenwriter Morrie Ryskind (A Night at the Opera, My Man Godfrey, His Girl Friday) fill the Footlights Club with a group of actresses who compete for our attention from the moment the film starts.

Gail Patrick, who played Carole Lombard's spoiled sister in My Man Godfrey, would have been a sufficient foil for Rogers in any other film, and Lucille Ball as Judy is fantastic in the picture, which would finally showcase her after a career so far full of often uncredited roles in pictures like Murder at the Vanities, Top Hat, Roberta and Follow the Fleet. She has glamour and comic timing; it's baffling how RKO overlooked her for so long.

And even they have to compete with Eve Arden as the presiding wit in the Footlights Club, dispensing droll sarcasm non-stop while draping a limp white cat around her neck. Ann Miller, apparently only fourteen when the film was made, plays Jean's dancing partner with an unforced sweetness. And representing the older generation is Constance Collier as Anne, a has-been who carries her notices around in her handbag, constantly recalls the once-great days of the "theatah" and appoints herself Terry's acting coach (just as Collier had coached Hepburn in real life.)

And finally there's Andrea Leeds as Kay, the creative heart of the group, an actress who had played to rave notices a year previous but is unable to land a follow-up role. She's kinder and less barbed than her housemates, accepting Terry before anyone else does, but she's wasting away in the shadow of her success, starving herself and behind in her rent.

Leeds was the only member of the cast to get an Oscar nomination, but her Kay seems underwritten despite her crucial role in the story; she's there to suffer and represent all the real talent that falls between the cracks. She spells out her situation when she says that "there's nothing else I can do and no one to go back to." In a film where nearly everyone gets to crack wise at least once, Leeds seems like she's in a different picture.

Stage Door began as a play by Edna Ferber and George S. Kaufman, full of contempt for the movies compared to the creative purity of theatre. It seemed a perfect vehicle for Hepburn and after paying a steep $130,000 for the rights, RKO immediately set about pruning all the anti-Hollywood barbs from the story.

In the end not a lot remained of the play except for some characters' names. When Berman signed La Cava to a one-picture deal to direct the film, he began his (in)famous deconstruction of the script, relying heavily on improvisation and rehearsing his actresses on the set of the Footlights Club in the morning and writing new pages for them to try out in the afternoon based on what they'd come up with before lunch.

Like many of La Cava's pictures, there was no script for much of the shooting, and the question of whether Terry or Jean would marry Menjou's Powell remained a mystery till near the end. Hepburn was handed the lines for a crucial speech she gives after her Broadway triumph on a scrap of paper just hours before shooting.

The banter between the actresses in their rooming house was based on overheard conversations; it's worth noting that the characters played by Arden and Miller are called Eve and Annie. The women even used their own clothes for their wardrobe.

While the major conflict is between Jean and Terry, the balance of power remains in the hands of the men who the women rely on for meals and evenings out and jobs. They're mercenary by necessity, whether it's Judy and Jean enduring the boorish attentions of Seattle lumbermen or Linda and Jean accepting the favours of Powell in exchange for better clothes and food and perhaps a shot at stardom.

Even Terry ends up unwittingly benefitting from the position of her father, the "Wheat King", who secretly backs Powell's latest play on the condition that Terry is made the star, hoping that it will flop and force her to give up her dream and come home. And even when she falls into this trap Terry has an edge over Powell; in a scene where he tries to seduce Jean in his penthouse apartment, Menjou shows off photos of his wife and son, humble-bragging that a sophisticated man like himself can be happily married and still go about a life of his own.

When he tries the same move on Terry, she notes that his wife is actually a model from a face powder campaign, while the photo of his son had been used for years to advertise the military academy her brother attended. Powell is forced to admit defeat and treat Terry as talent and not a treat. (This ladder of privilege was echoed in the salaries paid to the three stars, with Rogers getting a thousand dollars less a week than Hepburn, while Menjou was paid more than either woman.)

After excising the shots at the movies from Ferber and Kaufman's play, La Cava seems to presume that turnabout is fair play and paints a dire picture of the theatrical ideal produced by men like Powell, and the role that Kay longs to play, falling into despair when Terry is cast. The play is called Enchanted April, the sort of torpid, polite manor house drama where everyone has the same plummy mid-Atlantic accent, in which Hepburn is supposed to enter and utter lines like:

The calla lilies are in bloom again. Such a strange flower – suitable to any occasion. I carried them on my wedding day and now I place them here in memory of something that has died.

The line actually came from The Lake, a Broadway flop that Hepburn had starred in two years earlier. And right up until opening night Terry is awful – her delivery stiff, her manner unprofessional, obtusely protesting to the director and writer that acting isn't about emotion as much as logic, and that training is unnecessary.

It's baffling why poor Kay had staked so much on a role in such a stinker, but that's her task in the picture, where she leaves her sickbed to give a distraught Terry some advice and see the other girls off for opening night before the scene that won her that Oscar.

While the voices of her housemates echo up the stairwell, Kay's face takes on a faraway look. The voices give way to ones from her own opening night as she starts walking with grim purpose up the stairs and past the camera to the roof. The Production Code spares us the sight of Kay falling to the pavement like Ann Dvorak in Three on a Match (1932).

(Like so many movies, Stage Door presumes that suicide is an act of madness. This isn't at all consistent with what I've seen too many times: that it's often a calculated decision, made in the absence of any obviously strong emotion, and undertaken without any discernible warning. Despair doesn't have a flag to wave.)

Terry, who had made an enemy out of Jean by breaking up her liaison with Powell for her own good while taking the part everyone hoped Kay would get, redeems herself – first by taking all the grief and regret she feels after Kay's death and channeling it into Enchanted April, second by giving a curtain call speech protesting that she doesn't deserve the applause and that "I'm not responsible for what happened on this stage tonight."

(Great theatre, apparently, demands a blood sacrifice.)

This is enough to repair her budding friendship with Jean, and four months later Enchanted April is a hit and Terry is a star, though the newspapers report that the "eccentric" actress has chosen to continue living at the Footlights Club with Jean, Annie, Eve and the other women. As an ending it's defiant, satisfying and wholly ridiculous at the same time; but its lasting utility is letting audiences imagine the haughty, patrician Hepburn as a democrat worthy of the respect of someone like Ginger Rogers.

It's tempting to compare Stage Door with George Cukor's The Women (1939), but the later film has a spikiness that endures till the last shot, with little to make us imagine that even battling for recognition and parity in a world run by men is enough to create a persistent bond among women.

Some might even say that Cukor's film is the more realistic one, but this doesn't undermine the importance of Stage Door as the film that made it possible for audiences to overcome a reasonable distaste for what Katharine Hepburn represented and imbue her persona with what still seems, in the occasionally unflattering light, like an improbable common touch.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.