In all the decades I've been going to New York City I've never been mugged once. I had a friend who was mugged within five minutes of getting off the bus his first time in the city. The thing is, I'm sure it never ruined his experience of New York. Quite the opposite – I think being the victim of a crime scarcely a block from Times Square added to his sense of the place, both as reality and myth.

I wouldn't be surprised if he felt sorry for me, missing out on New York crime in the perfect location.

It's hard to imagine a show like Law & Order and all of its spin-offs lasting as long as it has if it was set in, say, Tampa or Duluth or San Jose. It isn't that crime doesn't happen in these places; it's that crime in a smaller city is bigger news; criminals in New York have to compete to get attention, and given the city's size and density, you can be unaware of each week's headline malefaction – especially now that newsstands have effectively disappeared from the streets. Crime happens in New York, but depending on who you are and where you live, a new restaurant or a museum opening will seem more important.

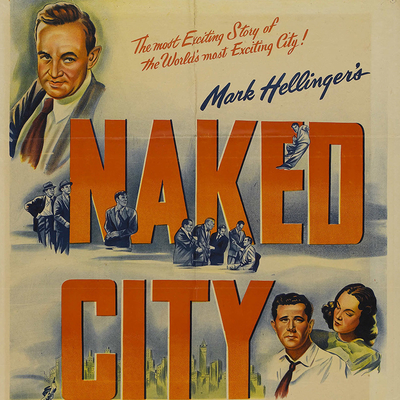

When producer Mark Hellinger and director Jules Dassin made The Naked City (1948), there was no hiding their intent on making a New York crime film, going out of their way to make the city – and not a backlot recreation – more than merely a setting. The film begins with the camera flying over Manhattan while Hellinger himself narrates in voiceover in lieu of opening credits, telling us that what we're about to see was filmed in the city itself, not in a studio, with the cast out on the streets.

"This is the city as it is," he says. "Hot summer pavements, the children at play, the buildings in their naked stone. The people without makeup."

The camera goes down into the buildings at one in the morning on a summer night, introducing characters without telling us if they'll be important later in the film. There' s a cleaning lady mopping a grand lobby, a newspaper typesetter and a DJ, society people playing cards in evening wear and a couple in a nightclub. And then the camera cranes up through the blinds of a darkened bedroom to show us a murder in progress – a blonde in a nightgown struggles as she's knocked out with chloroform by two men, one of whom decides he's not taking any chances, so he drowns her in her own bathtub.

This doesn't sit well with the other man, who we see next drunk on a pier by the river, complaining that he'll be judged by God for what they've done, but the other man knocks him cold with a piece of wood and dumps his body in the water. We have our crime, complete with accessory spare.

Hellinger was a fascinating man. He first made his mark as a teenager, organizing a strike in his Queens high school and getting expelled. He took a job as a waiter in Greenwich Village, which led to a career as an advertising copywriter, and then a gossip columnist for New York tabloids. He wrote sketches for the Ziegfeld Follies, plays and short stories, before writing the screenplay for Frank Capra's Broadway Bill (1934) with Robert Riskin, based on his own short story.

Hellinger kept publishing his syndicated column, while writing more stories that were turned into movies, like the Raoul Walsh gangster classic The Roaring Twenties (1939). He became a producer, first at Warner's., then at Fox and finally at Universal, where he had his own production unit, making made The Killers (1946) and The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947). The prison picture Brute Force (1947) was his first with Dassin, but The Naked City would be his last picture.

He died in 1947 of the congenital heart condition that had kept him out of uniform during the war. They renamed the 51st Street Theatre after him in 1949, but in 1989 it became the Times Square Church. Hellinger died at home after watching a final cut of The Naked City; you could say that the film's narration is his ghost.

As soon as the blonde's body is found the gears of justice begin to grind. Dassin's camera takes us to police headquarters and behind the door marked "Bureau of Telegraph" – the communications nerve centre of the NYPD. Jacks on a switchboard are plugged in to start each new gear turning – the hospital, the medical examiner, the technical research lab and finally the homicide bureau at the 10th Precinct.

(It's on West 20th Street according to Richard Alleman's New York: The Movie Lover's Guide, and still the 10th Precinct of the NYPD, though Alleman reasonably wonders why a Chelsea police station was tasked with investigating a murder that happened on the Upper West Side.)

The case is given to Det. Muldoon, played by that epitome of the Hollywood Irishman, Barry Fitzgerald. His second in command is Det. Jimmy Halloran (Don Taylor), until recently a beat cop in the Bronx, and before that a GI in Europe. The blonde's name was Jean Dexter – but not really; she'd changed it after escaping working class obscurity, got a job as a model in a classy dress shop but got fired for being too attractive to the clients' husbands. And she had a stash of expensive jewellery in her bedroom that's gone missing.

The first lead is a pair of men's pyjamas in the blonde's apartment belonging to a "Mr. Henderson" of Baltimore. The only problem is that everyone who saw him describes him differently. The prime suspect is Frank Niles (Howard Duff), a friend and sometime employer of the dead blonde; under examination he lies about everything from his war service to his business to his fiancée Ruth (Dorothy Hart), who had worked with Jean as a model at the dress shop. But he has an airtight alibi.

The movie started life as a story by Malvin Wald called Homicide – just in case you wanted to tie the film to another latter-day police procedural – and turned into a script by Wald and Alber Maltz. Around the same time Hellinger was given a copy of The Naked City, a book by freelance news photographer and renowned NYC character Weegee (real name Arthur Fellig). Weegee's book became the title of Hellinger's film and Weegee was hired as set photographer.

Hellinger and Dassin were so intent on their picture looking like a product of the real New York that they did something almost no one was doing at the time – they actually shot there. The studios had moved the city to their soundstages almost as soon as they'd moved west from facilities in Queens, New Jersey and elsewhere starting in the 1910s. Except for establishing shots and second unit footage, nearly every film set in and around Manhattan between the wars was shot on standing sets in Hollywood and Burbank.

But advances in movie technology and lighter cameras pioneered during the war made it possible to shoot on the streets of the city – though crowd control would be a constant problem during production. According to architect James Sanders, in a bonus feature included with the Criterion edition of The Naked City, 107 locations in Manhattan and the boroughs were used. There are a few obvious studio sets and rear projections, but for the most part the film uses real places from the midtown shopping district to Chelsea to the Lower East Side.

At one point during the endless leg work he has to do to investigate the murders, Taylor's young detective has a moment to stare out a window and admire the view, as almost everyone does when they're in some warehouse loft, high rise office or skyscraper with its collection of discrete panoramas. "There's your city, Halloran," someone tells him.

At another point near the picture's climax the detective has been disarmed and knocked unconscious by Garzah (Ted de Corsia), the killer, who gets ready to make his escape, taunting the cop prone on his tenement floor saying "This is a great big beautiful city. Try and find me."

Writing about Dassin's films in Somewhere in the Night: Film Noir and the American City, Nicholas Christopher says that The Naked City "was a model of the semidocumentary variety of film noir, in which New York City itself (photographed comprehensively in over one hundred different locations) is the focal point. As the critic Robert Ottoson points out, Dassin, who grew up in New York, exhibited in The Naked City 'an exactitude in depicting New York's tenements, office buildings, police stations, docks, bridges, and streets.'"

The Naked City frequently makes lists of classic film noir, but the picture is an uncomfortable fit with the genre. It's a crime film more than a noir, and one of the first clear models of a police procedural on film.

I like to joke that procedurals are what you get when you take a Sherlock Holmes story and remove the genius. The police procedural stresses that there's an order to be followed, religiously, when trying to investigate a crime, and respect must be given to the skills of the various professionals employed in the process, from crime scene photographers and fingerprint men to coroners and lab technicians. Fitzgerald's Muldoon is constantly cautioning his young assistant to calm down and be methodical rather than intuitive.

Which makes this kind of procedural inherently democratic in nature – distrustful of gifted minorities and arrogant rule-breakers and designed for the limited skillsets of the average man. Stamina is valued more than brilliance – never more so than during the chase scene at the film's climax.

One clear way that The Naked City departs from the classic noir is that its femme fatale is dead at the start of the story, the pictures heroes immune to her toxic charms. Jean was at the centre of a jewel theft ring, her most pitiful mark the doctor Halloran visits early in his investigation. Niles is her accomplice, a weak man accustomed to using everyone around him, but a poor criminal when things start getting tough.

The villain, Garzah, is glimpsed but only introduced near the end, when he goes on the run through his Lower East Side neighbourhood, familiar with every shortcut in this run-down but bustling part of the city. But he panics, killing a blind man's seeing eye dog with the gun he took from Halloran as he flees across the Williamsburg Bridge.

Unlike the Brooklyn Bridge, its famously picturesque neighbour downstream on the East River, Richard Alleman in New York: The Movie Lover's Guide writes that the Williamsburg Bridge "is usually a location for films that emphasize the gritty downside of New York City's mystique." In The Naked City it "provides a cold, erector-set-like setting..."

Unlike the Brooklyn Bridge its pedestrian paths are wide, while its lower levels are reserved for cars and subway trains. We watch a frantic, sweaty Halloran chase Garzah down the middle of its walkway, through the skipping ropes of children from the Lower East Side using the bridge as a playground.

In this way Dassin's film delivers the noir goods; in Somewhere in the Night Nicholas Christopher writes that characters' "innermost conflicts and desires are rooted in urban claustrophobia and stasis...Hence the obsessive emphasis on urban setting that are precarious and dangerous: rooftops, walkways on bridges, railroad tracks, high windows, ledges, towering public monuments (a Hitchcock favorite), unlit alleys, and industrial zones, not to mention moving trains and cars."

Cornered on the middle of the bridge, Garzah has nowhere to go but up, climbing the metal stairs in one of the bridge's towers, meeting his inevitable end there. Hellinger's narration delivers an epilogue, before using the famous words that would become a tagline when the movie inspired a TV series that ran on ABC from 1958 to 1963: "There are eight million stories in the naked city. This has been one of them."

Hellinger, narrating his film from the grave, gave himself some great lines: "Another day, another ball of fire rising in the summer sky. The city is quiet now, but it will soon be pounding with activity. This time yesterday, Jean Dexter was just another pretty girl, but now she's the marmalade on 10,000 pieces of toast."

At the end of the movie we see Fitzgerald's Muldoon pensively smoking his pipe on the roof of his apartment building with the city at night behind him. Niles broods in his jail cell while Ruth sits in the window of her bedroom on the Upper East Side. Halloran and his young wife wait for a subway train back to their home in Astoria, while Jean's grieving parents sit slumped on their worn wooden porch somewhere far away from the city's lights.

Hellinger muses on their loss, and the daughter "whose passion has been played out now. Her name, her face, her history has been worth five cents a day, for six days. Tomorrow a new case will hit the headlines, yet some will remember Jean Dexter. She won't be entirely forgotten. Not entirely, not altogether."

Hellinger's narration is the soft centre underneath the hardboiled exterior that finally elevates The Naked City to the ranks of great noir, despite its oddities. The picture did well at the box office despite what they say on the Criterion's bonus material, got an Oscar nomination for Malvin Wald and wins for Paul Weatherwax's editing and William H. Daniel's black and white cinematography. Most of all it tempted filmmakers back to New York City, leaving the backlot Manhattan streets out west to Seinfeld and Friends.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.