According to Apple, the premiere episode of Masters of the Air, the "sequel" to Band of Brothers and The Pacific, was the most-watched debut ever on their streaming platform. Which is proof that there's a robust audience for these technically cutting-edge but dramatically old-fashioned World War Two dramas, produced by Steven Spielberg's Amblin and Tom Hanks' Playtone.

It's hard not to see the appeal in a world full of moral equivalence and antiheroes so compromised they'd be called villains in a different era. None of these shows deny that war is hell; they go out of their way (with the assistance of top dollar digital and practical effects) to immerse us in the horror and violence but remain steadfast that this awful war was worth the cost, given the brutality of our enemies.

In the lead-up to Masters of the Air, there were reasonable concerns that the "evolution" of Hollywood in the fourteen years since HBO aired The Pacific would inject a good deal of retrospective handwringing into the story of the Eighth Air Force and its bombing campaign over Europe, but the new show was remarkably free of it – defiant, even, that despite the terrible toll in civilian casualties, it was justified by defeating Nazi Germany.

For history buffs and war film aficionados, it was difficult not to remember Twelve O'Clock High (1949), a film whose thinly fictionalized plot overlaps substantially with the history dramatized in Masters of the Air. It's certainly worth contrasting two very similar stories, one told when its audience would be full of veterans of the war depicted, the other when those veterans have effectively vanished.

This film begins with a sentimental journey. Harvey Stovall (Dean Jagger, who won an Oscar for the role) is visiting present-day Britain, and chances upon a toby jug in the window of an antique shop. The owner assures him it's nearly worthless, but Stovall insists on having it wrapped carefully. When we see him next he's on a train, then on a bicycle peddling along a country lane that takes him to an abandoned airfield.

Wandering the overgrown runway next to a boarded-up control tower, his memory draws him back to just a few years previous, when he was a deskbound major with the 918th Bomb Group, waiting for B-17s and their crews to return from a mission. One plane comes back damaged and does a belly landing on the field and everyone rushes to help the crew out of the plane.

We take it for granted that a war film will be bloody; with horror movies leading the way, effects crews in movies have pioneered anatomically explicit violence. And within minutes of bringing its audience back to the early days of America's air war in Europe, Twelve O'Clock High makes us imagine the kind of terrible things you might witness in the aftermath of a battle.

An airman crawls out, distressed, then turns to vomit over the wing of the plane. The men take out another man on a stretcher; his leg is broken, but that's not the worst of it – someone says that they can see his brain, that his skull was blown open by a 20mm shell.

Another crewman asks what they should do with the top turret gunner's arm, left behind after he was bailed out over France in the hope that he'd survive long enough to end up in a French hospital. Stovall asks for a blanket from the ambulance to wrap around the severed limb. A modern film would present all of this to its audience as a grand guignol.

(Remember the soldier whose leg was blown off during the D-Day scene in Saving Private Ryan, or the one searching for – and finding – his missing arm? The men staggering around on fire? The young soldier calling for his mother while holding his intestines with both hands?)

We hear about, but don't see, the terrible wounds after the offscreen air battle in Twelve O'Clock High, which is in black and white in any case. You might presume that taste and discretion and the Production Code would require this, and that you didn't need to be explicit when your audience would include men and women with vivid recent memories of such things. Or that a modern audience is so far from this kind of violence that they need to have their faces rubbed in it.

In either case it's clear that the filmmakers want us to leave civilian life and imagine a time and place – just recently, or decades past – when violence and death seemed to be the focus of most of mankind's energy.

The 918th is a unit in crisis: casualties are mounting and Major General Pritchard (Millard Mitchell), commander of the 8th Bomber Command (based on Maj. Gen. Ira Eaker, first commander of the real-life 8th) thinks that the problem is Col. Davenport (Gary Merrill), head of the 918, who's been overcome with an "overidentification with his men."

Discipline is lax both on the base and in the air; fatal mistakes are being excused by Davenport, who not only sees but feels the stress his men are experiencing early in the experiment that was "daylight precision bombing" by the U.S. Army Air Force. His loyalty to his men is reciprocated in kind, but they're still dying faster than other bomber groups in the 8th, and after talking to Davenport, Stovall and other men, Pritchard decides to relieve Davenport and replace him with the general's assistant chief of staff, Brig. Gen. Frank Savage (Gregory Peck).

Davenport and Savage are friends but very different men, and the 918's new commander begins by demoting air crew who he considers underperformers, putting the worst of them together to crew one plane piloted by Col. Gately (Hugh Marlowe), which he has renamed Leper Colony. He closes the officer's club and puts the whole group on training missions; in response all of the pilots put in requests for transfers, which Savage asks Stovall, a lawyer in civilian life, to delay passing up the chain of command with military red tape.

Twelve O'Clock High was based on a book written by Beirne Lay Jr. and Sy Bartlett, who had both served on the staff of the Eighth Air Force in Britain, where Lay commanded director William Wyler when he was making his masterpiece propaganda film Memphis Belle. Darryl F. Zanuck at Fox bought their manuscript while it was still unpublished for a whopping $100,000 up front, and before their book even had a title.

The novel was inspired by real events: the 918th was based on the 306th Bomb Group (306 x 3 = 918) and Davenport on its commander, Col. Charles "Chip" Overacker, who was relieved by Col. Frank Armstrong, the model for Peck's Savage. Even the awful aftermath of the air battle and its wounded crew was based on an actual incident that won a Medal of Honor for 2nd Lt. John C. Morgan, the co-pilot of a plane damaged in a raid over Kiel in 1943.

(Even that Toby jug Stovall buys is based on ones that had their face turned to the wall of officer's clubs when bomb groups weren't scheduled for a mission.)

Until late in the film this aftermath is the closest thing to a battle we see in director Henry King's picture. Twelve O'Clock High is less war movie than drama, and mostly takes place on the airfield and Quonset huts of the 918th's base near the fictional village of Archbury, or in the more luxurious staff headquarters of the Eighth. It's more a story about the demands of command than the costs of war, which is probably why the film has held up so well over nearly eight decades.

Despite making more than a hundred films over a career that started in the silent era, King is the classic journeyman director, never associated with a personal style or a particular genre. He made the original silent version of Stella Dallas (1925) and In Old Chicago (1937), a "disaster musical drama" about the 1871 Great Chicago Fire (surely not a crowded genre) that was nominated for a best picture and won Alice Brady an Oscar for supporting actress.

King got in early with war pictures with A Yank in the RAF (1941) before making a movie out of John Hersey's A Bell for Adano in 1945. His career high point was probably the mid-'50s, when he made the melodrama Love is a Many-Splendored Thing (1955) followed by a movie version of Rogers and Hammerstein's downbeat musical Carousel (1956). He obviously appealed to Gregory Peck, who would work with him again on The Gunfighter (1950), David and Bathsheba (1951), The Snows of Kilimanjaro (1952), The Bravados (1958) and Beloved Infidel (1959).

You could see the attraction of an actor like Peck to a director like King, who did not draw attention to himself. Peck seemed embarrassed by films that forced him to raise his voice or throw shapes, though there are times in Twelve O'Clock High where I might have liked to see Savage show a bit more of whatever conflict was brewing beneath his unrelenting drive to inspire pride in duty instead of mere camaraderie in the men of the 918th.

"Consider yourselves already dead," he tells his men by way of a pep talk. (It's the same advice "super soldier" Capt. Speirs, as played by Matthew Settle, gives frightened replacement troops in Band of Brothers.)

Try to imagine Kirk Douglas in the role of Savage. Or if that seems too much of an overcorrection, perhaps Henry Fonda. John Wayne turned it down, but Clark Gable was interested, and Burt Lancaster, James Cagney, Dana Andrews, Van Heflin, Edmond O'Brien, Ralph Bellamy, Robert Preston, Robert Young and Robert Montgomery were all rumoured to be considered for the film. Every name suggests a completely different version of Twelve O'Clock High; I'd opt for the one with Lancaster.

Peck himself turned it down, but agreed to take the part when he met King. If I wanted to be harsh, I could say that Peck's best performance in the film is when combat fatigue reduces him to a catatonic state at the end of the picture. Cruel, perhaps, but nobody does catatonic better than Gregory Peck (except perhaps Gary Cooper).

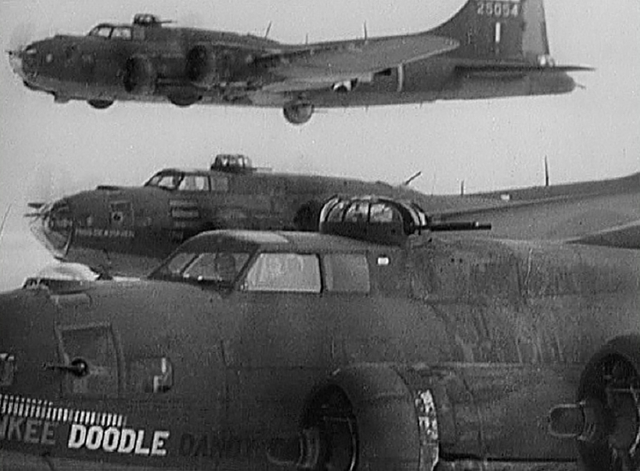

Avoiding scenes of air battles might have been a prudent move by Zanuck and King. It had only been four years since the end of the war but it took some effort to find enough airworthy B-17s to film when King settled on locations in Florida and Alabama, after scouting for them in early 1949, flying all over the country in his own Beechcraft Bonanza. We only ever see six bombers in the air during the film, but the producers managed to find a dozen for the picture, including the one that legendary stunt pilot Paul Mantz belly-lands at the beginning of the film, piloting the bomber solo for the crash.

(Combat footage shot for the picture would be recycled when ABC made Twelve O'Clock High into a TV show in the early '60s. I remember rushing home to watch it after school in the '70s, in a mid-afternoon block of shows that included The Rat Patrol, Combat! and Hogan's Heroes. I remember it being the dullest of the four shows.)

There are supposed to be less than a dozen airworthy B-17s in the world today, and Apple's Masters of the Air created theirs with digital effects, after building three replicas to film on the ground. Spielberg, Hanks and Apple had to deliver as much action as possible with their series (based on the book of the same name by historian Donald L. Miller), and they went to town with a crucial sequence in the third episode – the disastrous air raid on aircraft factories and ball-bearing plants in Regensburg and Schweinfurt on August 17, 1943.

This famously costly raid, handicapped by bad weather and worse timing, was a turning point for the Eighth Air Force and the 100th Bomb Group whose story is the focus of Masters of the Air (along with a subplot that takes in the Tuskegee Airmen). Sixty of the 376 B-17s that flew the mission didn't return, after delays and poor coordination and communication left them exposed to German fighter attacks for much of their time over Germany. The raid is also the basis for the key air battle at the end of Twelve O'Clock High that finally makes Peck's Savage snap under the strain.

King and his team worked within the considerable constraints of action filmmaking in 1949; there's no reliance on miniatures or obvious rear projection. They filmed as much as possible using their small squadron of salvaged and repainted bombers and cut it with actual wartime footage provided by the military. (The decision to film in black and white instead of colour was made to integrate the combat footage more seamlessly.)

With an obligation to satisfy an audience that expects real spectacle and the nearly limitless possibilities of digital effects, Masters of the Air presents the raid as a visual phantasmagoria – a dream (or nightmare) scene where the pilots played by Austin Butler and Callum Turner, the heroes of the story (based on real-life airmen Gale "Buck" Cleven and John "Bucky" Egan respectively) look out of their planes at a widescreen panorama of sky, clouds and destruction.

As flak explodes and German fighters rocket through the frame, bombers catch fire or explode, raining parts (and even men) past the windscreen of their planes. I can't speak for the realism of this scene; I don't think there are more than a few dozen men alive today who can speak to its accuracy. But the scene unfolds onscreen like a fever dream of aerial combat, and criticism of the series turned during this episode from mostly positive to loudly dismissive, with online catcalls about "atrocious" CGI extending to criticism of the story and acting.

A Forbes story on the reaction notes that the criticism might just be from a vocal and opinionated minority. (Which is a statement that you could apply to almost anything said on social media.) "This series is made for the same audience that enjoys the like of Avatar or the Marvel comic-driven superhero movies, all of which don't exist," said military vehicle history John Adams-Graf when interviewed by the magazine.

And he's right; audiences raised on battle scenes in everything from Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings pictures to Avengers: Endgame to Roland Emmerich's Midway are unlikely to be satisfied by the restraint in King's necessarily focused version of a disastrous air battle, or anything that doesn't fill the screen with epic carnage.

What I can say from with pure subjectivity is that Masters of the Air is nowhere near as satisfying as Band of Brothers, which depicted camaraderie in the face of horror and death far more effectively. It's not even as good as The Pacific, which was less successful at the task, mostly because it split our focus between three heroes over its ten episodes, none of which ever share the screen.

This might be a function of its subject: the peculiar thing about the air force in general and the Eighth Air Force in particular is how airmen's lives were divided between brief terrifying missions and long stretches on the ground, on base or on leave. The brutal casualty rate of Allied air crews in the European theatre might also have something to do with it: during the early stages of the bomber war they had a one in three chance of making it home after twenty-five missions.

It's still debated today whether "daytime precision bombing" ever really accomplished its goal, or if it was just a war of attrition: the trenches of World War One transplanted into the air. A lot of actors including Barry Keoghan (Saltburn, Dunkirk, The Eternals, Chernobyl), whose career wasn't nearly as high profile when he took a role in the series, just disappear from the series when their character is lost in action.

That all might be true. But I don't remember thinking that after watching The Battle of Britain (1969), and that was only a quarter the length of Masters of the Air. Though it did star Michael Caine, Robert Shaw, Christopher Plummer, Edward Fox and Ian McShane, and perhaps that's the problem – there's a measurable deficit of charisma in too many actors today. I found myself confused by so many young pilots sporting what looked like the same moustache.

The good news is that Masters of the Air improves with a subsequent viewing. The bad news is that it still isn't as satisfying as Band of Brothers after nearly a dozen. Even worse is that its nine hours, spectacular as they are, don't have a fraction of the drama of Henry King's austere wartime story about a man trying to convince the men he commands that their probable deaths serve a purpose they might not understand, in the service of a military doctrine that might not actually work.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.