My dear friend Kathy Shaidle was fond of saying that The Who were "better than that stupid band you like." So it only follows that Quadrophenia, the movie they produced about the British youth subculture where they started, is better than anyone else's youth subculture movie.

So – better than Trainspotting, Suburbia, Singles, American Graffiti, The Wanderers, Reality Bites, Dazed and Confused, This is England, Jubilee, Rude Boy, Northern Soul, Absolute Beginners, 24 Hour Party People, Performance, Backbeat, Control, That'll Be the Day, Velvet Goldmine, Stardust, Young Soul Rebels, Rebel Without a Cause, The Wild One, A Hard Day's Night, Sid and Nancy and Endless Summer?

Perhaps. It's certainly a film that revived the long-dead subculture it was about, though that might have been simply a matter of timing and luck.

It's definitely proof of my maxim that there's no such thing as a "period movie," since every movie, no matter when it's set, is really about the time it was made. And Quadrophenia, a 1979 movie based on a 1973 concept album based on events that happened in 1964 (or 1965), is really about being young in the late '70s and nostalgic about being young around the time you were born.

Which is quite an accomplishment, and I'm sure Pete Townshend wouldn't agree, but hear me out.

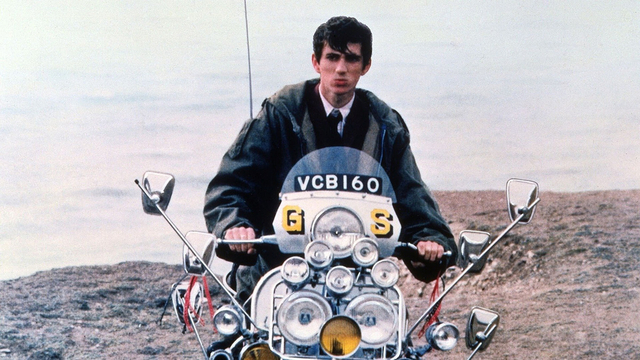

We first see Jimmy Cooper (Phil Daniels) at dusk, silhouetted by light on the water as he walks toward the camera. After an abrupt cut we see him ride through nighttime London on his Lambretta scooter as "The Real Me" by The Who blasts from the soundtrack. Fans of the Who's double album would know that the song introduces the hero and his split personality – a diagnostically dubious "double bipolar" disorder that will trouble Jimmy through the whole story.

The scooter and his US Army surplus parka make Jimmy as a Mod – a British subculture that had already transformed itself once or twice by 1964 (or 1965; everyone argues about when the film is set) and would do so at least one more time before subsiding into the catalogue of British youth subcultures that wax and wane but never quite disappear. Jimmy is an everyman, or more particularly an everymod – indistinguishable from the small army of sharply dressed young people who filled London and the UK's smaller cities around the time the Beatles had their first big hits.

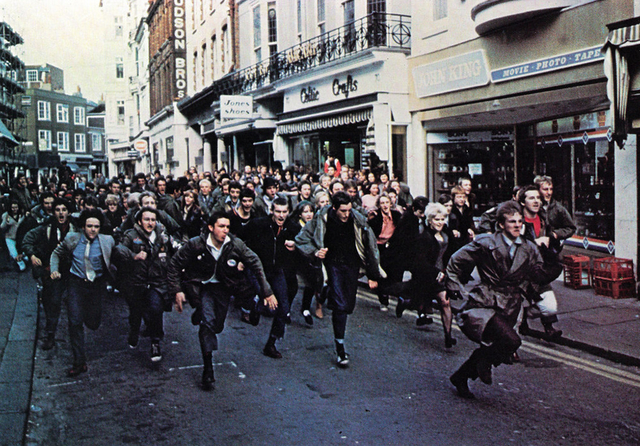

It was a big ask to introduce Jimmy and his tribe without much context, at least for American audiences who (with the exception of diehard Who fans and '60s music obsessives) knew the word as an adjective, not a noun. British audiences, however, would have known what they were looking at right away, as many had vivid memories of the height of Mod infamy when they fought running battles with leather-clad, bike-riding "Rockers" in seaside towns like Margate and Brighton.

(In the press conference scene in A Hard Day's Night (1964) Ringo is asked by a supercilious journalist if he's a Mod or a Rocker. "Um, no, I'm a mocker," he replies, though truthfully he was only recently something more like a Teddy Boy, a slight precursor of the Rocker, while his fellow Beatles had styled themselves as Rockers in full leathers, though they lacked the requisite motorbikes. A deft parry by the drummer, who was asked the same question by Ready, Steady, Go! host Cathy McGowan while they were making the film, and likely the beginning and the end of most Americans' knowledge of Britain's great youth subculture rivalry at that time.)

Jimmy defines himself as a Mod, and his Mod friends comprise the most vital part of his world as he's bored with his job and dismayed by his family. Director Franc Roddam, fleshing out the very cinematic story painted by Townshend in the Quadrophenia album – which came with sound effects on the records and a gatefold booklet illustrated by photographer Ethan Russell, shot in and around the band's Battersea recording studio with local kids playing roles – filled the screen with an astounding young cast whose subsequent careers on film and television are a testament to his instincts.

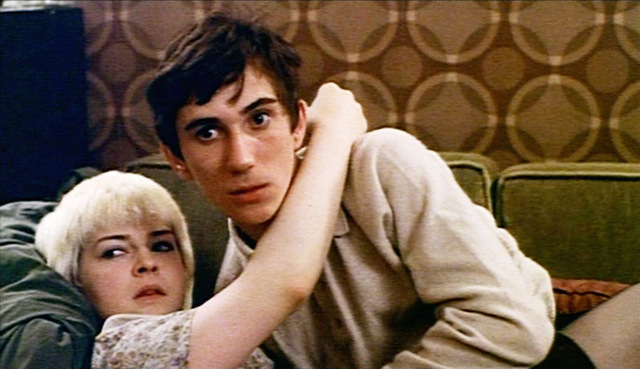

There's Dave (Mark Wingett), Jimmy's friend and eventual rival; Chalky, played by the wonderfully expressive Philip Davis; Monkey (singer Toyah Wilcox), who nurses a crush on Jimmy; Spider (Gary Shail), the youngest and most naïve member of the gang; and Ferdy (Trevor Laird), their resident drug dealer. Jimmy is infatuated with Steph (Leslie Ash), who's casually involved with Peter (Garry Cooper), a slightly older Mod whose family is adjacent to organized crime, though she's openly flattered by young Jimmy's attentions.

While most of them live with their parents, they have discretionary income and ambitions that their parents could never have imagined. They have mobility thanks to cheap imported Italian scooters they lavish with decals, headlamps and mirrors, and jobs that allow them to buy tailored clothes, spend nights in cafes and clubs, and weekends in pursuit of thrills, fueled by amphetamines. They're the first generation free from national service, and in Harold MacMillan's "You've Never Had It So Good" Britain, a whole new economy has evolved to serve their needs and wants, much like their American counterparts.

As Julie Burchill, a particular favorite of Kathy's, wrote in Damaged Gods: Cults and Heroes Reappraised:

Mod represented the raised expectations of the most intelligent and metropolitan of working-class youth. Mod was the gap between full employment and unfulfilled aspirations, the missing link between bomb sites and Bacardi ads. The earliest Mods were besotted with all things continental – to them Modernism was a package tour of the soul.

The original Mods of the late '50s had fetishized Italian design, French movies and American bebop; subsequent iterations had moved on to Tamla Motown and finally British bands like the Kinks, the Who and the Small Faces in search of something edgier and more danceable. And these younger Mods had found an enemy worth battling in the leather-clad Rockers.

Mods were the first generation of British youth who didn't look to Britain's wartime allies, the Americans, for evidence of the good life, but the continent that their fathers regarded as the home of battlefields and recent enemies. Europe was the future, and for an aspirational subculture intent on escaping the past, the Rockers embodied the past, with their love of "old" American rock and roll (it had been six whole years since Elvis entered the army Jerry Lee Lewis brought his underage wife and cousin on a UK tour; five since Buddy Holly died) and British motorcycles like the Triumph and the BSA. They were dirty where the Mods longed to be clean, and looked for all the world like troops press-ganged to defend the world of their parents – a world the Mods were dying to escape.

Or at least that's how Mods are explained today, or explain themselves in retrospect. Like most youthful social movements I doubt if that much philosophy or calculation was in play at the moment of genesis.

Thankfully Phil Daniels' Jimmy isn't tasked with articulating all of this, which would be an unfair burden; most of it is inferred and can be learned in the copious criticism and literature that's sprung up to explain both Mods and the film. His Jimmy is like most young people – confused and even incoherent, years from being able to explain what he really wants, with language acquired through experience and hindsight.

The marvel of Daniels' performance is watching the emotions well up and contort the actor's face and body, his eyes on stalks, constantly searching for threats, friends and affirmation. His Jimmy has the kind of personality that a drug like speed does no favours, though I've always wondered if Townshend's insistence on mental illness being the source of Jimmy's torment isn't a misreading of a painful but reasonable response to a society that gives someone like Jimmy very few options on the menu.

Daniels almost didn't get the role; he had just returned from filming Zulu Dawn, a prequel to the 1964 classic Zulu, and had contracted an illness in South Africa that left him weak, his tongue coated in a green fuzz that Roddam found revolting. He was up against John "Johnny Rotten" Lydon for the part, who Toyah Willcox helped coach through what everyone agrees was a very good (though sadly lost) screen test. And he might have got the part if the film's insurers hadn't objected vehemently to casting the former Sex Pistol, just in time for Daniels to recover and deliver the audition that got him the part.

(I can speak for both me and Kathy here, I think, in wanting the chance to visit the alternate universe where Lydon played Jimmy, if only for a couple of hours.)

Roddam copied the immersive rehearsal process of directors like Mike Leigh by giving his core cast scooters and having them hang out during pre-production, making them a little gang, with Who bassist John Entwistle introducing them to old Mods (many then in their thirties!) to get lessons on dancing, riding and fighting.

The result was a film that, despite many, many well-documented lapses in strict historical accuracy, has a lived-in feel, the dynamics between characters well established, even with peripheral cast members or ones that have only two or three scenes, like Ray Winstone's Kevin, an old childhood friend of Jimmy's.

They meet in a public bath, one of the last in London during filming. (The galvanized tin tub hanging by the back door of Jimmy's home is a cue that their two-up/two-down backing on to the railway tracks has rudimentary plumbing at best.) When Kevin starts singing Gene Vincent's "Be Bop a Lula" in the next stall, Jimmy retaliates with "You Really Got Me" by the Kinks. A scrub brush tossed over the partition nearly brings them to blows but they recognize each other and meet up afterward at a pie and mash shop, where Jimmy is shocked to see Kevin in full Rocker leathers.

Kevin had been in the army, stationed in Aden – another dismal chapter in the shrinking of Britain's empire – but chafed under the discipline and got himself discharged. Visiting Jimmy in his garden shed one night where he's working on his scooter, they talk about why their choice of clothes and conveyance seems to have put a barrier between them. Kevin says they're all the same, but Jimmy disagrees:

"Look, I don't wanna be the same as everybody else. That's why I'm a Mod, see? I mean, you gotta be somebody, ain't ya, or you might as well jump in the sea and drown."

It's as far as he can articulate the most important choice he's made in his life so far, but it only makes sense to Jimmy, who is still unaware that he has more options than have been presented to him. Jimmy thinks there's something essential in Kevin's decision to be a Rocker. "I never realized," he tells Kevin in the pie shop.

"What, am I black or something?" Kevin asks.

"You ain't exactly white in that sort of get-up, are you?" Jimmy responds, to which Kevin responds with a considered shrug. The exchange will trigger younger viewers today, but it beautifully portrays people explaining their reactions when they're struggling to find the rhetoric nothing in their life has provided.

Winstone would have perhaps the richest career of all the film's young cast (he had just starred in Alan Clarke's Scum, which was often shown on double bills with Quadrophenia at the time, and his career highlights include Nil by Mouth, Sexy Beast, Cold Mountain and The Departed) and his scenes with Jimmy give us a glimpse of a real friendship that might have spared the young Mod a lot of torment. Kevin becomes a victim of random Mod street violence one night in Shepherd's Bush Market, taking a beating that Jimmy instigates but is unable to stop when he recognizes his bloodied friend.

The film is peppered with great little performances. Everyone, and especially the cast, has taken a shot at Sting, just on the verge of stardom with The Police, playing the Ace Face – the Mod trendsetter who mostly just glowers and grimaces through his scenes. But keep an eye out for Timothy Spall, later a regular in Mike Leigh films alongside Philip Davis, as the projectionist at the advertising agency where Jimmy works as a mail boy.

Mod had the rare distinction of admitting that, despite its strict but evolving standards on clothes, hair and music, its essential stance was inchoate – a wide-eyed, incoherent reaction to an overwhelming world embodied in the Who's first big hit, "I Can't Explain". (It might be why Mod never embraced any particular politics or party – a rare feat in British youth subcultures.)

When the band debuted it to their fans at the Goldhawk Club in 1964 after appearing on Ready, Steady, Go!, it went over so well they had to play it over and over again. Mod legend Irish Jack Lyons, one of their most devout fans (and rumoured to be an inspiration for Jimmy), went backstage to tell Townshend that he had written an anthem that summed up everything the movement was about.

"So Jack," Townshend remembered saying to his fan, years later, in what he recalls as a patronizing tone. "So you want me to write more songs for you about why you can't explain what it is you want me to explain, and I can't explain what it is that you want to explain?"

"That's it!" Irish Jack exclaimed.

(When Townshend brought out an autobiography in 2013, both Kathy and I had to read it. When we finished I remember telling her that, with respect to the book's title, Who I Am, I still hadn't an effing clue what that might be, even after nearly six hundred pages.)

Mod would evolve at least one more time, taking on a psychedelic dandy's wardrobe when bands like the Who and the Small Faces released songs like "I Can See for Miles" and "Itchycoo Park", but by the end of the '60s it was considered over, its energy and constituents dissipating into new subcultures like skinhead and suedehead, soul boy and Northern Soul. The aspirational ideal of Mod disappeared in response to decreasing economic opportunity, and these subcultures became ripe for political recruitment.

But like Rockers with their ton-ups and roadside cafes, and the Teddy Boys that would still inexplicably turn up at rock and roll revival concerts in the '70s, it never really went away, and when Roddam and his crew arrived in Brighton to film the riot scenes for Quadrophenia, an open call for extras produced 3,000 Mods and Rockers on their Vespas and Triumphs.

Quietly, beneath all the sound and fury of punk, a Mod revival had been building, its most visible avatar Paul Weller and his band The Jam coming out of Woking, the kind of working-class suburb that had always produced Mods. And this, dear reader, is where I come in.

In his book Mod: From Bebop to Britpop, Britain's Biggest Youth Movement, Richard Weight writes that the late '70s Mod revival "helped to anglicise punk rock, which had arrived from America, making it more recognisable, more palatable and ultimately more meaningful to young Britons with little knowledge of, or interest in, the intellectual radicals who fostered it from 1972 to 1976." He explains that:

"Over the next five years, Mod took several forms: it was an acknowledged influence on punk music and fashion during the cult's early, most controversial, phase from 1976 to 1979; from 1979 to 1982 it inspired a copycat Mod revival by working-class youths nostalgic for the optimism of the 1960s and disappointed by what they saw as the middle-class posturing of punk's shock troops. At the same time, a new subculture, Two Tone, emerged which fused the politics and style of punk and Mod to create the first truly multiracial youth culture on either side of the Atlantic."

Punk was supposed to revolutionary, but it also looked back hungrily at all the pop and rock music that came before prog rock and stadium tours and concept albums, drawing the latest in an endless series of lines in the sand. (And even John Lydon would admit his love of prog bands later.)

Think of Lydon stepping out in Teddy Boy drapes he got from Vivienne Westwood's boutique, or the Clash covering rockabilly cult hits like "Brand New Cadillac," their hair done up in impeccable greaser quiffs. Punk talked about year zeroes and destroying the past, but it also revived and revered its own pantheon of bygone heroes; it might have been the last real new beginning in rock music, while ushering in the "eternal now", where the whole of music history is up for grabs.

Quadrophenia was a lightning bolt for the Mod revival simmering under punk, galvanizing membership in the scooter clubs that never went away, inspiring new Mod bands (the Chords, Secret Affair, Purple Hearts, the Merton Parkas) that never went anywhere, and filling the shops and back page ads in the UK music press with nasty slim cut suits, two tone shoes, Harrington jackets and RAF bullseye t-shirts.

So by the time Quadrophenia opened in Toronto the audience at a nearly empty afternoon matinee at the Varsity Cinemas were treated to me and my high school pal Cadillac Bill standing up after the lights came up in our drainpipe jeans and army surplus parkas with Union Jacks sewed on the back. Yes, dear reader, for a year at least I was a teenage Mod revivalist.

I remember hearing a woman behind us stage whisper to a friend, "Didn't they learn anything from the movie?"

And it's true: Roddam's film is about the dangers of losing your identity in a group, and ends with Jimmy alone by the seaside, rejecting Mod, at the lowest point in his young life. But that didn't matter to me: like so many young people I was besotted by the style and music and aspirational optimism of Mod, and I knew exactly what Irish Jack was saying about "I Can't Explain."

But I'd sell the parka to a classmate a year later, spend my junior year as a Ted before embracing '40s jazz and a wardrobe I copied from film noir. A couple of years after that I was into hardcore punk. My youth was a whiplash journey through subcultures; I was insufferable and that's fine. Time had presented a working-class boy like me with so many more options than Jimmy, and by the time Mod broke big in my hometown, with scooter clubs in affluent suburbs like Leaside and North Toronto, I knew if I saw a subculture reaching out to embrace me, I'd start running in the opposite direction.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.