When the poet W.H. Auden called the years leading up to World War Two "a low dishonest decade" in his poem "September 1, 1939", you have to wonder if this was simply a case of perfect hindsight. Were sensible people really living for years with the near certainty that another war was on its way? If so, it must have been intolerable; if not, it would explain a lot.

Proof of this dismal mood is actually abundant even in entertainment – like Alfred Hitchcock's 1935 thriller The 39 Steps, one of the director's earliest and greatest successes. It's the story of a man who accidentally stumbles onto proof that a foreign power is actively conspiring to gain advantages in peacetime that will benefit it immensely with the coming of war – a war that it's intent on winning.

Screenwriter Robert Towne famously said that "all contemporary escapist entertainment begins with The 39 Steps." It's certainly true that every movie or TV show about a hero pursued all over the map by implacable enemies had its form codified by Hitchcock while he was still a British director, a few years from moving to Hollywood. But you have to wonder – just how "escapist" is a film predicated on the audience accepting that war was on its way, sooner or later?

The film was based on a novel by John Buchan, the Scottish writer and politician who would, as Lord Tweedsmuir, become governor general of Canada that year. The first thing Hitchcock did was to change the setting of his story from early 1914 to the present day, maintaining the same sense of looming menace that made Buchan's book topical when it was published in 1915.

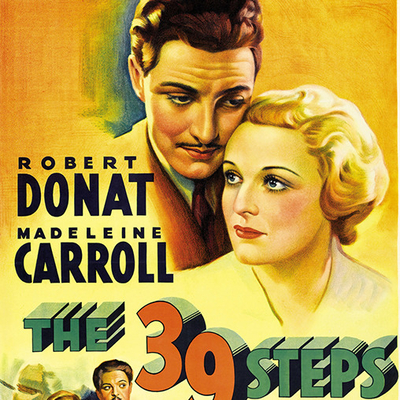

The film begins with Richard Hannay (Robert Donat) taking in the acts at a London music hall. He watches as Mr. Memory (Wylie Watson) is introduced – a man gifted with total recall who commits fifty facts a day to memory. Hannay is a Canadian, we learn, when he asks Mr. Memory what the distance is between Winnipeg and Montreal.

Heckling from the balconies leads to brawl at the bar, which turns into a stampede when somebody fires a gun and starts a stampede out of the hall. Hannay chivalrously helps a woman (Lucie Mannheim) navigate the crush to the street outside, where she brazenly picks him up, suggesting they go to his place.

Their subsequent banter has Hannay assume she's some kind of prostitute, which she neither confirms nor denies (she calls herself a "freelancer") but as soon as they're at his flat she hugs the walls, afraid of being seen by some men waiting on the street outside, who begin ringing Hannay's flat from the phone booth.

She speaks with a German accent and says her name is Annabella Smith (though they both know it's not her real name) and she confides to Hannay that she's an agent-for-hire, currently in the employ of the British and in possession of intelligence about a foreign spy ring that has stolen secret plans for a warplane engine. The men outside are muscle, in the employ of a master spy whose identity can only be confirmed by a missing joint on his pinky finger. She needs shelter for the night before heading to Scotland to meet someone.

That's as much as he learns before she staggers into his bedroom later that night, a knife in her back and a map of Scotland in her hand, with a remote spot called Alt-na-Shellach circled. Hannay evades the men outside by telling the milkman making his morning rounds that he needs to slip out after an assignation with a married woman, and that the men waiting outside are her brother and husband. The milkman appreciates the situation and lends him his coat, hat, horse and cart.

(It's typical Hitchcock that a whole lurid world of louche sexual behaviour is presumed to underpin a morally upright one – must be there to allow characters the leeway to act in the extreme situations of his films.)

On the run from the law he gets a ticket on the Flying Scotsman to find out just what Annabella Smith was killed to conceal. When policemen board the train and begin searching for him he spots an attractive blonde with glasses (Madeleine Carroll), barges into her compartment and kisses her. He tells her who he is but pleads his innocence; she turns him in to the police anyway and he makes his escape as the train passes over the Forth Bridge just outside Edinburgh.

Traveling by foot across the highlands, pursued by police and hounds and overhead by an autogyro (technically the weakest shot in the film), he finds refuge for the night with a crofter (John Laurie) and his much younger wife (Peggy Ashcroft, who would go from the set to playing Juliet opposite John Gielgud's Romeo at London's New Theatre). Despite guessing his identity she intuits his innocence, but her stern husband presumes a flirtation and gives Hannay away to the police; his wife gives Hannay his coat and lets him escape out a back door.

Hannay makes his way to Alt-na-Shellach and the home of Professor Jordan (Godfrey Tearle), who hides him from the police. Presuming he was the contact Annabella was traveling to see, he tells Jordan the whole story, but admits he doesn't know the identity of the ringleader of the spy network, only that he's missing half his pinky. Jordan nonchalantly holds up his hand to reveal his truncated digit, and after offering him the chance to kill himself, shoots Hannay point blank.

Hitchcock economically cuts to Hannay alive, in the office of the local sheriff while he tells the story of his escape from Jordan's house, after a prayer book in the crofter's coat stopped the bullet. The sheriff is sympathetic until reinforcements arrive, when he tells them to arrest Hannay and that the professor is one of his closest friends. They get a handcuff on him but he escapes by jumping out a window and into the street, eluding the police long enough to blunder into a political meeting, where he's mistaken for a renowned Liberal politician booked to speak in support of a local candidate.

Donat was Hitchcock's first choice for Hannay – he'd seen the actor onstage in Shaw's Saint Joan, and in a double role in James Bridie's now-forgotten A Sleeping Clergyman, where he was taken with Donat's "queer combination of determination and uncertainty." He'd recently had screen success with Alexander Korda's The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933) and The Count of Monte Cristo (1934) – highlights in a movie career made sporadic by chronic asthma.

Donat's Hannay is a prototype of the Hitchcock hero – diffident and a bit aimless until galvanized by events that usually overtake him out of nowhere, where he reveals ingenuity and even bravery that nobody would have suspected, the hero least of all. His performance is a dry run for Cary Grant in To Catch a Thief and North by Northwest, with the same abundant charm and useful appeal to the opposite sex (like the crofter's wife, a city girl marooned in the country).

Buchan had conceived Hannay as a practical man of action eager to escape the torpor of predictable middle-class life; a mining engineer, soldier and spy who would be the main character in five novels. What he did not conceive was much of what Hitchcock, his wife Alma, screenwriter Charles Bennett and humorist Ian Hay (hired to contribute oddball characters and comic banter) added to his story.

Above all was a romance – entirely missing from Buchan's novel – with Pamela, the blonde from the train, who shows up in the audience when Hannay begins improvising his speech and brings back two men she presumes to be policemen to arrest Hannay. They're really Jordan's muscle, and they take Pamela with them as they drive through the darkness to rendezvous with the local elements of the 39 Steps – the name given to the spy network in the movie. (In Buchan's book they're actual steps.)

They handcuff Hannay and Pamela together, much to our hero's amusement, and they're shackled together when Hannay manages another escape, dragging Pamela with him through the gorse and burns until they come across a convenient tavern and inn, where Hannay threatens to shoot his unwilling hostage if she doesn't maintain the fiction that they're newlyweds whose car has broken down.

Carroll wasn't Hitchcock's first choice for Pamela, but she was a big star in the UK, and her offscreen personality was the opposite of her cool and haughty one onscreen. This made her perfect as Pamela, the first of Hitchcock's "icy blondes" whose recurring roles in his films would become key to future decades of critics psychoanalyzing the director's abundantly kinky and perverse subtexts, and his own (often inappropriate) on-set behaviour.

In his book Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, Patrick McGilligan describes how the director put off introducing his co-stars until the first day of shooting, where he handcuffed them together in preparation for shooting their escape through the moors, then made a big show of losing the key, wandering off for what some witnesses said was hours.

While his assistant went off to find the director, "the stars fidgeted, then grew flustered, then developed the very problem Hitchcock had imagined: how to go to the bathroom. They were annoyed with Hitchcock, but also with each other – and before long they were acting not unlike their characters."

This abrupt introduction would help create the abundant sexual chemistry for the film's most risqué scene, when the couple is alone together in their room at the inn and Carroll attempts to take off her wet stockings. Donat's hands wander all over Carroll's legs in a scene that would have been tame in a pre-Code Hollywood picture just a couple of years previous, and it's among the first of Hitchcock's coy sexual humiliations of his heroines.

Hitchcock's film is only 86 minutes long, and it's by far the most concise and fast-paced of all the big and small screen adaptations of Buchan's novel. The first remake was produced by the Rank Organization in 1959, with Kenneth More as Hannay in a contemporary Cold War setting, where plans for a ballistic missile are stolen by the titular spies, and More spends most of this leisurely comic retelling stealing clothes.

Rank would remake it again in 1978, returning the setting to Buchan's original one on the eve of World War One, with Robert Powell as Hannay. The title also reverted to a reference to actual stairs, though this time they're located in the clock tower of Big Ben, which would be the scene of an extravagant action sequence featuring Powell hanging from the clock's minute hand.

The BBC took a shot at Buchan's story in 2008, which was also set in 1914 and starred Rupert Penry-Jones as Hannay. Lydia Leonard played Victoria, a love interest roughly analogous to Carroll's Pamela except this time she was a suffragette and secret agent; the BBC obviously felt it was time to make Hannay share the screen with a girl boss who was every bit his equal.

With Hitchcock's original forming a template every subsequent version would pick and choose from Buchan's novel, though some elements remain consistent. Scotland is always Hannay's first destination, a wild detour that only serves to put our hero on a train, where he may or may not escape by climbing down a bridge that may or may not be the Forth Bridge.

It also allows the film to dive deep into comic Scots stereotypes, like an inept and hapless constabulary, or John Laurie's tight, hostile crofter. While on the run in the highlands, Hannay will be followed by some sort of aircraft, though in each version after the original it would be a real plane, and by the 2008 version it would carry machine guns and strafe Hannay.

(Hitchcock himself would have another go at the plane and the man on the run in North by Northwest, which is just a thinly disguised but glamourized rewrite of his 1935 original.)

The luckless agent who implicates Hannay in the conspiracy might be male or female but they always die with a blade in them; in every film Hannay is called upon to deliver a madcap, improvised speech when his identity is mistaken. And in nearly every version the heroine is called upon to show some leg – even when it's made by the BBC. (Shockingly, the 1978 remake where Powell's Hannay sports an impressive head of permed hair is the most chaste of them all.)

But by returning to the 1914 setting of Buchan's story, the last two remakes lose the sense of geopolitical urgency that gave Hitchcock's original (and to a lesser extent the 1959 version) an added dimension. The stolen state secret in Buchan's story was Royal Navy defense plans; in Hitchcock's it's the plans for a silent aircraft engine, and it's missile plans in the 1959 film, every one reflecting how audiences imagined wars would be fought.

You could shrug and say it doesn't really matter; the object of Hannay's quest is just another one of Hitchcock's MacGuffins, tugged out of the hero's reach as it leads him on an ever more improbable but exciting adventure. And while that's true on paper, I can't imagine audiences in 1935 assuming the unnamed country sponsoring the spy network was anything other than Hitler's Germany, and that must have given the thriller an extra charge – a deeper black in the stygian shadows of Bernard Knowles' camera work.

When Buchan published his book in 1915 the First World War was in its first year, and his plot had all the plausibility of actual history. But the public had been willing to imagine a coming war with Germany as early as 1903, when Erskine Childers published The Riddle of the Sands, which told the story of a German invasion of Britain foiled by a low-ranking official in the Foreign Office on a yachting trip near Heligoland. As long as Kaiser Wilhelm was in power it looked like conflict was inevitable, though how catastrophic it would be was beyond imagining.

(Childers' book would be made into a movie starring Michael York and Jenny Agutter in 1979, a year after the second Rank remake of The 39 Steps; how does one account for all this nostalgia for the world just before the Great War just as Margaret Thatcher was coming to power? Write your answers below.)

Two years after Hitler took power it might have seemed to older people that history was repeating itself. Judging by the youthful embrace of pacifism– the Peace Pledge Union was founded in 1934 and actually reached its peak in membership in 1940 – it was popularly understood that war was on the menu, but that if you simply refused to order it might go away.

While PPU membership was never high, pacifism was a serious topic, and provided the political atmosphere that made appeasement official government policy. In their history of Britain between the wars, The Long Weekend, poet Robert Graves and journalist Alan Hodge wrote that "the phrase 'the next war' was used without any calculation as to who would be fighting whom...Most war and anti-war talk was now a fanciful discussion of the horrors and glories of 'the next war'." PPU members refused to take part in civil defense and ARP drills and protested legislation for air raid precautions.

When war finally came, the poet Stephen Spender wrote that "from the point of view of an anti-fascist like myself, those who actually conducted and fought the war were – with the exception of Winston Churchill – curiously unconcerned with the evil of Hitler...There was something magnificently arbitrary about Britain's reasons for fighting: it was not so much that Hitler was evil as that he had gone too far."

"The attitude reflected the mood of the British public. Four years in which the Nazis had been given all – indeed far more than that which was denied to the Weimar Republic – had led to increasing demands from Hitler and the increasing demoralization of our side which was the result of always giving way...It was very characteristic of the British, having given way all along the line, at the very end of it, when all seemed already abandoned, to say 'No.'."

In the year that The 39 Steps was released the Anglo-German Naval Agreement was signed, which was supposed to limit Hitler's navy to 35 per cent the size of the Royal Navy. He would ignore it almost immediately and denounce it by 1938, and in any case the real priority was the army and the Luftwaffe.

Pacifists might believe that war could be made to look unreasonable if you looked cross enough, and politicians might have thought that Germany had a reasonable limit to their demands if only they could find it, but the average person knew what was coming, and who would do the fighting and dying when it started. In the meantime it was pleasant to watch Donat's Hannay get the better of Hitler's spies and have some fun along the way.

A year later Hitchcock would make Sabotage, based loosely on Joseph Conrad's The Secret Agent (another novel, from 1907, that anticipated the coming European conflict) and set in the present. In 1938 he made The Lady Vanishes, a thriller on a train traveling through a Europe tensely preparing for war. Neither film mentions Hitler or Germany.

In March of 1939 Alfred and Alma Hitchcock were on a boat to Hollywood, and five days after Hitler invaded Poland he began filming Rebecca. He began work on Foreign Correspondent in the new year, and though U.S. Neutrality Acts prevented him from mentioning Germany explicitly in the picture, nobody was being fooled by the time the picture closes with Joel McCrae's American reporter broadcasting as bombs start falling on London:

"It's too late to do anything here now except stand in the dark and let them come as if the lights are all out everywhere except in America."

Even as the bombing started it was still possible to find a law or a politician trying to make you pretend nothing was happening.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.