One aggravating peculiarity of baby boomers – one of many, to be sure – was to imagine their parents and every preceding generation afflicted with a lack of self-awareness. From farm hand to Harvard man, they were all benighted rubes, overwhelmed by the speed of change and in thrall to authority and received wisdom. Irony was born out of thin air, in the smoky funk of a dorm room when someone put on a Lenny Bruce record after Rubber Soul.

While it's far from the most egregious error their cohort ever forced upon the world (Earth Day and the music of Jefferson Airplane were far worse) it's among the flimsiest, blown to ash simply by mentioning MAD magazine, the Ernie Kovacs shows that ran on NBC and ABC from 1956 to 1962, nearly every Looney Tunes cartoon produced after 1937, and the uneven but fascinating films directed by Frank Tashlin.

Listing Tashlin is a bit of a cheat since he worked at Termite Terrace between 1936 and 1946, making classic Looney Tunes like The Woods are Full of Cuckoos (1937), Plane Daffy (1944) and A Tale of Two Mice (1945). Before Tashlin, the other only director who began his career in cartoons was Gregory La Cava (My Man Godfrey, Stage Door, Fifth Avenue Girl). It's a tiny, select group that includes Tim Burton and Brad Bird.

Tashlin drifted into a job at Looney Tunes after working at both Fleischer and Ub Iwerks and drifted from there to writing gags for comedians like the Marx Brothers and Lucile Ball, punching up scripts for movies like The Fuller Brush Man and The Paleface before being drafted to finish The Lemon Drop Kid (1951), with Bob Hope, after director Sidney Lanfield left the picture.

He began working with Jerry Lewis on Artists and Models (1955) and had another hit in 1956 with The Girl Can't Help It, still considered among the best early rock and roll exploitation pictures. Tashlin had drifted from high school dropout to successful Hollywood director, complete with a signature style that would see him dubbed an "auteur" by French critics. It would be time for him to make a statement with his next movie.

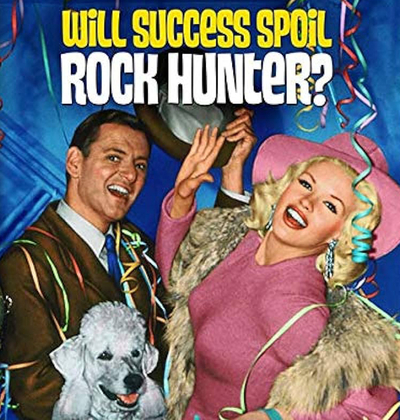

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? begins, like The Girl Can't Help It, by breaking the fourth wall. Tony Randall performs a one-man-band routine in the corner of the screen, playing along with the 20th Century Fox fanfare on drums, trumpet and double bass, before complaining about "the fine print they put in an actor's contract these days."

He sets up the picture and introduces his titular character – a writer working for a big Madison Avenue advertising firm – and while the credits roll we get a series of parodies of typical TV commercials from the time, all of them overpromising and underdelivering. The camera descends into the canyons of midtown Manhattan where we follow Rockwell Hunter into the offices of La Salle Jr., Raskin, Pooley & Crocket where he's a low man on the creative totem pole, ignored by the CEO, Irving La Salle Jr. (John Williams), and under the direct supervision of VP Henry Rufus (Henry Jones), who speaks in his own breezy, self-invented slang.

Hunter is guardian to his teenage niece April (Lili Gentle) and engaged to his secretary Jenny (Betsy Drake), though his scant wages and April's upkeep have deferred their nuptials indefinitely. Even worse, the agency is on the verge of insolvency with the imminent departure of Stay-Put Lipstick, its biggest client, and Rufus and Hunter are looking at losing their jobs if they can't come up with a Hail Mary pass by the client meeting the next day.

Enter the film's bimbo ex machina. April is the president of the midtown Manhattan fan club for Rita Marlowe (Jayne Mansfield), a pneumatic Hollywood movie star who descends on the city in a Lockheed Constellation airliner, after informing the press that she's looking for "seclusion" (unaware of what it means but suspecting it might be indecent). She's fleeing Hollywood after her Tarzanesque beau Bobo Braniganski (bodybuilder Mickey Hargitay, Mansfield's future husband) was caught with another blonde.

Skipping school to greet Rita at Idlewild Airport, April accidentally overhears the name of the hotel where the star is staying. Rita and her personal assistant Violet (Joan Blondell) cook up a scheme to make Bobo jealous by fabricating a torrid affair with the first man they can find. Into this walks Hunter, who had cooked up an ad campaign for Stay-Put Lipstick featuring Rita at the last minute and needs to talk the star into signing an endorsement deal.

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? began as a play written by George Axelrod, author of the play Billy Wilder based The Seven Year Itch on, and writer of screenplays for Bus Stop, Breakfast at Tiffany's and The Manchurian Candidate. He would later write, produce and direct Lord Love a Duck (1966) and The Secret Life of an American Wife (1968).

Axelrod's play was produced by Jule Styne, directed by the author, starred Mansfield as Rita Marlowe and played on Broadway for a year, but when Axelrod's play about a fan magazine writer who makes a Faustian deal with the devil was purchased by Fox studio head Buddy Adler (to get Mansfield out of her contract with Styne) he gave it to Tashlin, who re-wrote it entirely, retaining only Mansfield's Rita.

Mansfield is remembered today as one of several knock-off competitors for Marilyn Monroe – nicknamed "the smartest dumb blonde" and the best regarded in a crowded field that included Mamie Van Doren, Cleo Moore, Kim Novak, Tina Louise, Carroll Baker, Barbara Lang, Joi Lansing, Sheree North, Barbara Nichols, Carol Lynley, Stella Stevens, Anita Ekberg, Greta Thyssen and Diana Dors. (Some of these actresses would transcend or escape the Monroe stereotype; many would not.)

Nobody would deny that Rita Marlowe represented precisely what Mansfield was – a facet of the Monroe archetype, which had a powerful hold on America's fantasy of the feminine ideal at the height of the postwar boom. Even Monroe herself would be pressed into playing a take on the archetype as The Girl in Wilder's movie version of The Seven Year Itch.

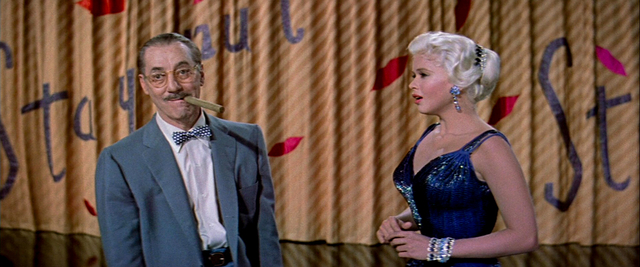

Mansfield's Jerri Jordan, the talentless gangster's moll in The Girl Can't Help It, was a character Monroe might have played if her star power had been slightly diminished, but Rita is a winking parody of Monroe herself, played with a breathy voice and non-stop wheezing squeals by Mansfield, accessorized by a poor poodle who gets his fur dyed in increasingly garish patches of colour over the course of the picture. And her girl Friday, Blondell's Violet, is a veteran assistant to movie bombshells going back to the silent era; Violet tells her boss that she used to be a looker herself, as Blondell was a pinup starlet in the pre-Code days, a variation of an archetype back when the ideal was Jean Harlow.

But Rita isn't a dummy; she shows glimpses of keen intelligence in the brief moments when she drops her bubblehead act. She knows how to manage the press, the studio and her image as well as anyone around her with a financial interest in it, and sets about moulding Hunter into the image of her "Lover Doll" as soon as he blunders into her scheme to make Bobo jealous, using him to play the whole of the machinery that's made her a star – studio, media and fans.

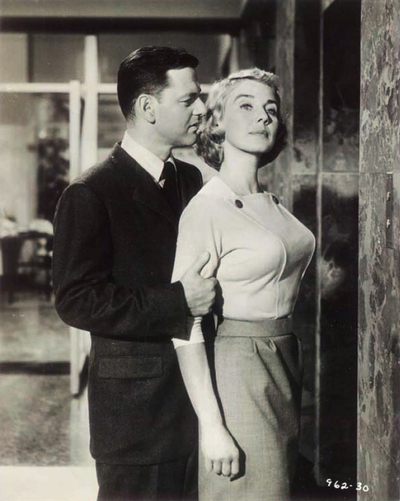

Randall's Hunter is the everyman – the lucky schmuck whose life is transformed with a kiss from the princess. It was a variation on the part played by Tom Ewell in The Girl Can't Help It, but Randall was an unusual choice by contrast with the hangdog Ewell.

Tony Randall had a sexual ambiguity that was hard to overlook in the '50s and '60s, as it was a huge part of his onscreen persona, playing second fiddles alongside Rock Hudson and Doris Day in Pillow Talk (1959), Lover Come Back (1961) and Send Me No Flowers (1964), and a similar role next to Yves Montand and Marilyn Monroe in Let's Make Love (1960). This epicene fussiness was embodied by Felix Unger in the TV series The Odd Couple, where much of the comedy was based on Felix being the platonic "wife" to Jack Klugman's boorish Oscar Madison.

On the scale of male movie stars ranging from merely asexual to coded as obviously gay, Randall was on the near side of Paul Lynde, in a neighbourhood that included Clifton Webb. He would end up playing an openly gay man in the early '80s on the NBC sitcom Love, Sidney, though little evidence ever emerged that the twice-married actor, a sophisticated man with a passionate interest in the arts who died in 2004, wasn't straight.

The big gag in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? is that the ectomorphic Hunter can become a heartthrob as viable as Hargitay's Bobo with the mere intimation of sexual proximity to Mansfield's Rita. Within a day of meeting her he's on the front page of every newspaper in New York; in a few days he's an international sensation, Rita's "Lover Doll", a sex symbol in his own right, chased by mobs of teenage girls, lusted after by women who had ignored him just a few days previous.

Much of the comedy in Tashlin's picture is about how the average American allowed their life and identity to be mediated by movies, press and television. While the whole world swallows the improbable fiction that Hunter is a charismatic alpha male, the women around him are moved to re-shape themselves in the image of Rita.

While he's able to persuade his fiancée Jenny that he has no interest in Rita beyond securing her lipstick endorsement, she nonetheless concludes that she needs to make herself look more like Mansfield, and starts a regimen of push-ups to increase her bustline that only renders her comatose from exhaustion, her arms stuck in position from the relentless exercise. (Hunter even finds his teenage niece in bed, frozen in the same attitude.)

The doctor he calls to check on his fiancée tells him that he's seeing this kind of thing a lot lately, and that it's total bunk – the only way to get those results is by doing a little shopping. (The first successful breast implants were still a few years in the future.) Not long after we see Jenny shopping for brassieres; she shows up for work with her new endowments and the breathy squeal to go with it.

The other target of Tashlin's satire, though, is the advertising industry and television, which in America was based around a group of privately owned networks that made their money with commercials and sponsorships. He took a jab at the huckster tone and perfidious nature of TV advertising in the credit sequence, and the juvenile inspiration for commercial jingles when Hunter pitches a campaign to Rufus based on chickens singing about lipstick to "Old McDonald Had a Farm".

In the make-or-break meeting the next day, Rufus' best ideas are a line of lipsticks flavoured with booze, and a national kissing contest pitched at children. He's utterly untroubled by the venal, even indecent nature of his ideas, and surprised when the CEO turns them down, scandalized.

Facing the likelihood that he and Hunter will lose their jobs, he imagines that he'll have no trouble finding another one; Hunter on the other hand will probably end up writing for fan magazines again, as talent has nothing to do with success in advertising. Elsewhere it's confidently stated that the great thing about advertising is that it requires no thinking.

Tashlin takes another swipe at TV in a brief intermission break halfway through the film, when Randall breaks the fourth wall again to congratulate the audience for coming to a cinema when they could have stayed at home with the technological marvel that is their television set. It's a throwback to Ewell's tuxedoed introduction to The Girl Can't Help It, where he flicks the edges of the screen to make it stretch to Cinemascope, then testily commands it to transform from black and white to Deluxe colour.

But when Randall starts speaking the screen shrinks till it's a little squat rectangle around the actor's head. The colour disappears and the picture goes in and out of focus, then loses its vertical and horizontal hold, becomes deluged in a blizzard of "snow" or fades in and out of a negative image. The sound stutters, then bursts into squalls of static.

Anyone over fifty remembers this as an average evening in front of your TV set, when weather, interference, weak signals, faulty wires or dying vacuum tubes sent you across the carpet to fiddle with the tiny tuning buttons on the rear or back of the set, or simply start slapping the side and top of the TV with your hand until the appropriate degree of abuse set things right again.

This peevish attack on TV was nothing new from Hollywood: It's Always Fair Weather (1955), the last film Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen made together, also mocks the race to the bottom on network programming, and the oily, insincere pitches of TV ad campaigns. Dan Dailey's ex-GI is an ad man from Chicago who hates his life and the stress of his job.

You didn't have to look far in the press, in quality magazines, or in movies or television to read or see complaints about how advertising had become both hectoring and omnipresent, all while consumer spending power had reached levels unseen in history. That we were becoming richer while the culture was actively conspiring to make us dumber was a complaint going back to the '20s, when writers like H.L. Mencken made misanthropy mainstream and made his reputation in the process.

(Randall's first major role on Broadway was newspaperman E.K. Hornbeck in Inherit the Wind – a character based on Mencken.)

But there's nothing highbrow about Tashlin or his movies. There were other movies and directors who drew inspiration from cartoons; the sight gags and physical comedy in Kelly and Donen's Singin' in the Rain come straight out of MGM cartoons made by Tashlin's Termite Terrace colleague Tex Avery.

Directors like J. Lee Thompson would match Tashlin's oversaturated, surreal style with pictures like What a Way to Go! (1964) and John Goldfarb, Please Come Home (1965), inspired by the success of Tashlin's pictures with Jerry Lewis. And Bob Fosse was squarely in Tashlin territory with Sweet Charity (1969), not to mention his choreography for Damn Yankees (1958), directed by Donen and George Abbott.

Tashlin's broad, silly, horny pictures are as much part of the zeitgeist of Hollywood before the boomers as any bruised melodrama by Douglas Sirk or the increasingly bleak westerns made by everyone from John Ford to Budd Boetticher. Something was souring in the land of plenty, but Tashlin had the unique set of skills to find it not merely funny but ironic.

So why does Tashlin's satire feel dated today – so much that many young viewers seem unable to perceive it as such? It might be because, despite his raucous tone, isn't an inherently cruel director, and his satire is edged with fondness – for the people in it, and for the hypertrophied culture that it's goofing on. There's plenty of what the kids today call cringe in the film, but little of the cruelty that's a condition for the best of today's comedy.

In an essay on the film, Jonathan Rosenbaum writes that Tashlin had to discard nearly all of George Axelrod's play because it simply wasn't compatible with his worldview: "Hatred for the mass market – best sellers, Hollywood, advertising – is something close to a constant in Axelrod's work. Given that Axelrod was himself entirely a creature of the mass-market, this invariably led to diverse forms of self-hatred, despite (or, again, perhaps because) of the fact that so many of his heroes were writers."

"The world-view of Tashlin, by contrast, is decidedly sunnier. Finding American culture ridiculous isn't necessarily or invariably equivalent to hating it; in Tashlin's case, on the contrary, it becomes a means for appreciating it."

There's a point at the end, after all of the characters get what they want without entirely convincing us it's what they need, when Tashlin lines them up for a curtain call that Rosenbaum calls "Brechtian". It's as if he's delivering the happy ending demanded by the studio while holding it at arm's length between thumb and forefinger.

As Rosenbaum writes, even when Tashlin "acknowledges being implicated in what he's satirizing, he's good-natured and relaxed about it – making his populism and optimism seem genuine rather than forced. He has a charming way of being devastatingly critical, affectionate, and hopeful at the same time."

The stridency and sham claims made by advertising in the '50s were broadly mocked; it would seem that nobody was being fooled. So it's not surprising that this doesn't resonate with subsequent generations, who have developed an abiding fondness for the more artful TV ad campaigns of their childhood, so much that cumulative weeks can be spent watching YouTube compilations of commercials from the '70s, '80s and '90s. You have to wonder who has the deficient sense of irony.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.