Gene Hackman played his last movie role twenty years ago, in a dud of a political satire called Welcome to Mooseport co-starring Ray Romano. Since then, he has written four novels (in addition to one he co-wrote before retiring) and narrated two television documentaries on the Marine Corps. In 2008 he appeared in an episode of Diners, Drive-Ins & Dives on the Food Network. Late last year photos were published of him eating in a Wendy's parking lot and fueling up at a gas station in his Santa Fe, New Mexico home, looking every one of his 93 years.

He looked like he was enjoying himself – like a man who had snuck out of the house to enjoy a chicken sandwich without telling his wife. Or at least he looked like a man who was grateful he hadn't taken a role in No Hard Feelings or The Marvels. Articles on Hackman have speculated that poor scripts and the dismal state of franchise-frenzied Hollywood motivated his retirement, the former actor has been discreet, saying it was for health reasons.

Still, after two Oscars and a filmography that includes Bonnie and Clyde, The French Connection, The Conversation, Superman, Mississippi Burning, Hoosiers, Unforgiven, Crimson Tide and The Royal Tenenbaums, there has to be some regret finishing your career with Welcome to Mooseport.

When director Arthur Penn's Night Moves was released to good reviews but poor box office in 1975, Hackman had the misfortune to follow it up with another flop, Lucky Lady – a period comedy directed by Stanley Donen where he co-starred with Liza Minnelli and Burt Reynolds, which was called "strident, forced hokum" by Variety and "ridiculous without the compensation of being fun" by Pauline Kael in the New Yorker.

Hackman could have packed it in at this point, and left Hollywood to race sportscars or renovate houses. But he knew that another decent script was on its way – if not a French Connection at least a Reds or A Bridge Too Far. It was the kind of career that could balance out the occasional All Night Long – a flop that lost its money mostly because casting Barbara Streisand bloated its budget. But we don't talk about Lucky Lady or All Night Long anymore, just as nobody remembers Welcome to Mooseport.

We do, however, still watch Night Moves, either as a hallmark of '70s neo-noir films (a robust genre that includes Chinatown, Klute, The Long Goodbye and The Friends of Eddie Coyle among many others) or as a film that functions like a time machine back to the moral slough that was the '70s.

It is, after all, a film whose poster carries the tagline "Maybe he would find the girl... Maybe he would find himself."

Hackman plays Harry Moseby, a private detective who was once a pro football player, famous for a great play during a losing game in 1962 with the Oakland Raiders. He's a modern guy who drives a 1967 Ford Mustang in "lime gold" – the kind of car a pro football player might have been given but never bought for himself.

He's not above asking for money from his wife, who has an apparently flourishing antiques business while Harry works out of an old office straight out of the Sam Spade playbook, complete with painted letters on the pebbled glass door. The only modern-looking thing in the office is his Code-a-Phone 700 answering machine, which will have some significance later in the story.

Harry's wife Ellen (Susan Clark) wants him to leave his business and take a job working for a big data-driven agency run by his friend; she calls his job, even his lifestyle, "a joke." He discovers that she's having an affair the night he goes to meet a client instead of going to see Eric Rohmer's A Night at Maud's with her. (Hackman has a famous line of dialogue comparing a Rohmer film to watching paint dry – an offhanded criticism that has followed Rohmer's films around ever since.)

He sees his wife leave the theatre and get in another man's car – a Mercedes coupe with the vanity plate "SUMTOI". (That has got to make the sting of infidelity even worse.) Harry tails them and traces the man to his house the next day. Marty (Harris Yulin) is a tasteful kind of guy despite the vanity plate, with a Malibu beach house full of art in a style we'd call "shabby chic" today, but which just signaled middle-class bohemian in the '70s.

Harry confronts Marty, who seems to know a lot about him; apparently he's a major topic of pillow talk between Ellen and Marty. Marty, who listens to classical music and walks with a cane, expects the tough guy ex-football player to get violent, but Harry is unable to take it to that level, even ashamed that it's expected of him. The two men act like they could have been friends in a different situation; apart from cheating with another man's wife, Marty seems more decent than Harry's actual friends, as we'll learn later.

The job Harry preferred to the Rohmer comes from Arlene (Janet Ward), a former actress who admits she had looks but little talent, but who struck it rich when she married a movie producer with a fondness for biblical epics back in the '50s. They had one daughter – Delly (Melanie Griffith), short for Delilah.

You can't help but speculate if screenwriter Alan Sharp based the husband on independent moguls like Samuel Bronston (King of Kings, The Fall of the Roman Empire), Frank Ross (The Robe, Demetrius and the Gladiators) or Sam Zimbalist (Quo Vadis?, Ben Hur). Everybody in Harry's world appears to be in the business or Hollywood-adjacent. Perhaps even Marty is a failed novelist who came west and ended up writing scripts.

Arlene's marriage to the mogul didn't last, especially after she cheated on him with Tom (John Crawford), the man who would become her second husband. She got nothing in the divorce but Delly got everything in the mogul's will, including a trust fund, a house and money, on the condition that Delly still lives with her mother.

Which she doesn't; just sixteen, she took off with her "freak" erstwhile boyfriend Quentin (James Woods) for a film set in New Mexico, where she hooked up with a cocky stunt pilot named Marv (Anthony Costello) who had also slept with her mother.

"There's nothing like having a mother and a daughter," Marv tells Harry when the detective visits the set. "It gives you a kind of perspective, you know what I mean?"

This is what characters in a film like Night Moves consider a deep thought; it's not a judgment on the film itself, but a way of understanding how painfully it evokes the '60s moral hangover that was the '70s for anyone who had the bad luck to live through it, and especially if you were a young person.

Harry's guide on the New Mexico set is Joey (Edward Binns), boss of the stunt crew and another old friend who moved in Arlene's orbit and might have been one of the men who, as Harry is told while trying to hide his unease, dangled little Delly on their knee. He has a theory that the girl is out for revenge on her mother by sleeping with her former lovers; this hunch leads him to the Florida Keys, where Delly's stepfather Tom is living the low-rent Margaritaville lifestyle with his younger girlfriend Paula (Jennifer Warren), running boat and airplane charters and capturing dolphins for the pet trade.

Tom is a friend of Joey's and Delly is there, but there's an immediate spark between Harry and Paula, who fills the femme fatale role in this neo-noir, albeit one who wears denim and frosted lipstick instead of figure-hugging gowns. Tom seems to get along fine with his stepdaughter, but he's eager for Harry to get her back to Los Angeles.

"I want that kid the hell out of here," he tells Harry. "I get pretty foolish with her. Well, you've seen her. God, there ought to be a law." Harry responds that there are.

Griffith was just sixteen when Night Moves was shot, and it's fair to say that like Delly, she was growing up fast. (Warner Bros. waited until the actress was eighteen to release the film thanks to an underwater nude scene. You have to wonder just how that logic works.) She was the daughter of actress Tippi Hedren and grew up in a house filled with the big cats from her mother's animal sanctuary. (This was the basis of Roar (1981), where Griffith and Hedren co-starred in a film directed by Hedren's second husband, Noel Marshall.)

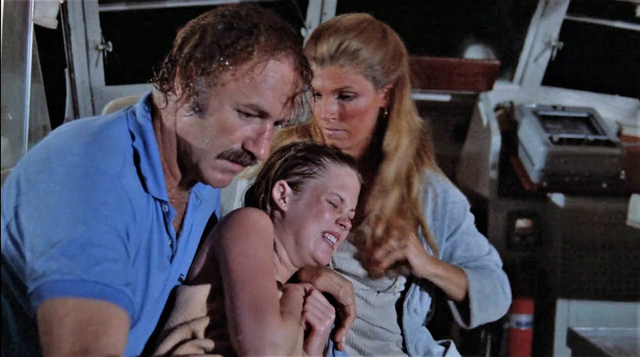

She met 22-year-old actor Don Johnson when she was just fourteen and married him in 1976. The marriage lasted six months (though they'd remarry again in 1989) and Griffith started dating Ryan O'Neal, who was sixteen years older. Like Scott and Warren, Griffith is topless in Night Moves, though the film makes a point that Harry's interest in Delly is strictly (and sadly) paternal. He's the only person who's both kind and appropriate with her, comforting the girl when she has a nightmare after they discover a body in an underwater plane wreck.

When writing about another '70s film, The Ice Storm – albeit one made in the '90s – I recalled that, from the perspective of a young person, the decade presented a non-stop spectacle of adults making bad choices and trying to tell us they'd make sense when we were older. (They didn't.) All while taking an inappropriate interest in us while the culture at large broke with precedent and played cheerleader. In case you were wondering why, nearly a quarter into the new century, sex seems utterly broken.

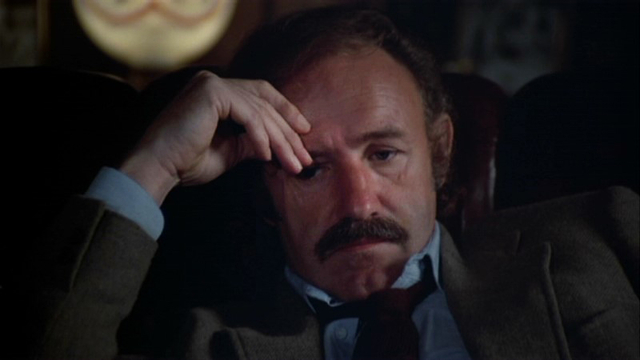

In essays about Night Moves, Hackman's Harry is framed as embodying a crisis in masculinity in the '70s. He's a manly man, whose brief fame in the NFL attracts other, even more manly men to him – like Joey, with whom he seems to share an easy night out after filming until the stuntman suddenly slams a younger man's face into his table when he knocks over their drinks. Harry acts embarrassed by the casual violence that's expected from him and struggles to express feelings for which he has no vocabulary.

"Harry Moseby is a character who both fills the Sam Spade mold while also being constructed in opposition to it," writes Madison Brek on the Film School Rejects website. "To simply call him the antithesis of characters like Spade would be misleading; he still maintains masculine authority and traditional noir eroticism. But where Spade's masculinity is reactionary, Harry's is progressive. It is a masculinity that has space for vulnerability, one that is not built upon a violent and threatening presence, and most importantly, one that relates to the women of this story as people rather than sex objects or reductive film noir archetypes of women."

"Harry still looks like a remarkably distinctive reimagining of the archetypal LA gumshoe," Jonathan Murray writes at Cineaste.com. "Eminently, enjoyably capable of both hard-boiled punch and punchline when matters require, Hackman also brings an intensely moving sense of physical and emotional fragility to proceedings.

Warren's Paula is probably the worst person he could meet at the best point in his life, and their attraction grows despite her inability to answer his questions with more than riddles, diverting him at one point by asking him where he was when Kennedy was shot.

"Which Kennedy?" he asks.

"Any Kennedy," she replies.

(Even if the film was playing in another room, you'd know it was a '70s picture just from this dialogue.)

Paula tells Harry that she's hiding with Tom in the Keys "convalescing from a terrible childhood"; she describes the standard trajectory of the fallen woman in the movies, from schoolteacher to waitress to stripper to hooker. She's with Tom because he's the only man she knows who gets nicer when he gets drunk.

You expect that Harry might find a way out of his crumbling marriage with Paula, especially after they sleep together, but he returns to L.A. with Delly shortly after, returning her to the chaos and neglect of her mother's house, intent on trying to repair his marriage. This leads to a scene where Hackman and Clark enjoy a post-coital fondue in bed. Once again, it's hard to imagine any single scene summing up the – there's no better word – ickiness of the decade in a snapshot.

Harry decides to leave the private dick business and packs up his office, where he accidentally turns on his Code-a-Phone to hear the first part of a message left by Delly, but he turns it off. It's a bad move: not long after he learns that the girl, who had taken a job doing movie stunts, has died in a car accident that left Joey, the driver, in a body cast. He suspects Quentin of fiddling with the car's brakes. Confronting him, he's told that the body in the plane out in Florida was Marv the stunt pilot; that was the message Delly had left him.

This sends Harry back to Tom's place in the Keys to try to solve the case – his last job – but it sends the story into the realm of both improbability and classic '70s paranoia. Way back at the start of the film, when Harry got the job helping Arlene find Delly, he was admiring a big piece of pre-Columbian pottery in a display case in the office of his buddy who ran the computerized detective agency. He was told that this once-worthless stuff sold to tourists was suddenly worth a fortune, and the film's finale reveals a smuggling operation run by Tom, Joey, Marv and Paula out of the Yucatan, flying pieces of Mayan artwork into the country.

The secrets and double-crosses coalesce into a conspiracy that leaves nearly the whole of the cast dead and Harry bleeding from a gunshot wound, alone on a boat turning in a slow circle out in the Gulf of Mexico. (Take that metaphor with you as you leave the theatre.) It's a late-arriving MacGuffin only slightly bigger than finding Delly, and it firmly places the film among the countless existential mood-pieces that sprawl across every genre of '70s movie.

"I want to know what it's all about," Harry insists to Paula, though he's forced to admit near the end that "I didn't solve anything."

The film's title is a pun that comes from Harry's obsession with chess. He shows Paula a classic strategy from a game played in 1922, where a chess master missed his opponent setting up his knight's moves leading to a checkmate: "He played something else and he lost."

I somehow avoided watching Night Moves for decades and assumed that the film's soundtrack would feature Bob Seger's hit single of the same name, which was on the radio constantly (and which didn't come out until a year after the film was released. Seger explained that the song was really inspired by George Lucas' American Graffiti.)

I was shocked to hear a jazz-funk score by Michael Small. (Small provided the scores for several pictures redolent of '70s paranoia, including Klute, Parallax View, Marathon Man and The Star Chamber. It turns out the sound of dread in the age of shag carpet and bell bottom slacks is thick with the bubbling tones of a Fender Rhodes electric piano.)

Hackman admitted in interviews that it would take the '70s for an actor with his looks to get a shot at leading man roles, though he always wanted to play the conventional swashbuckling hero in a big studio picture. His Harry Moseby is considered crucial in the pantheon of troubled men he'd make his specialty during the decade: "Pappy" Doyle, Harry Caul in The Conversation, Reverend Frank Scott in The Poseidon Adventure and Gene Garrison in I Never Sang for My Father.

My friend Ken Anderson, writing in his Dreams Are What Le Cinema is For blog, takes a dissenting view, saying that Hackman "seemed to be giving the same performance in film after film. It took Superman (1978) to shake some of the cobwebs off of his acting style. Mercifully, he's always an interesting actor to watch; intelligent and sensitive, yet always a kind of violent tension lurking beneath the surface."

And he's right – Hackman settled into a sullen torpor as the decade progressed, and it took Lex Luthor to bring out a manic energy as bracing as that "violent tension"; without the comic book villain it's hard to imagine later roles like FBI agent Rupert Anderson, Sheriff Bill Daggett, Harry Zimm or Royal Tenenbaum. It would have been nice to get another decade or two of that Hackman, but in the Hollywood of the new century, we can no longer have nice things.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.