Jacques Tati's career looked like it was over when he started filming Trafic in the spring of 1969. Playtime (1967), his masterpiece, had bankrupted him so utterly that he had to sell his family home and the rights to his previous films. He had lapsed into periods of depression and thought about giving up, but somehow managed to cobble together what would turn into an unwieldy co-production with partners in Holland and Sweden who would ultimately abandon him in despair or anger.

Playtime is part of that small group of films that were savaged by critics and flopped in theatres, only to redeem themselves with the passage of time. It was the most ambitious, controlled film Tati ever made, shot in 70mm on a specially constructed set known as "Tativille", built on land leased from the city of Paris – a set so large and complex that it required its own power plant. All of this was necessary because Tati found it difficult to control traffic and crowds filming at Orly airport.

Coming after Playtime, Trafic looked like a step backwards – Tati himself admitted that it could have been made between Mon Oncle (1958), his much-loved Oscar-winning third feature, and Playtime. In mood, however, it's the work of a man who has been through it all and has martialed his last heroic reserve of energy for one last statement. Or as David Bellos wrote in his book Jacques Tati: His Life and Art, "perhaps the most lasting impression of the whole film is of the exhausting experience of having spent a couple of hours by the side of a motorway."

Tati said that his research for Trafic involved two hours one Sunday morning on a highway overpass watching cars leave Paris. And it's with cars that Tati starts his picture, the camera following sheets of metal being pressed into door panels at the DAF auto plant. A subsequent scene is unmistakably Tati: in a vast exhibition space about to host a car show, we watch men in suits walk across the floor where booths for exhibitors have been laid out with pieces of string.

The string is invisible to us, looking down on the space from a balcony or concourse in this wide shot, so all we see are men in suits stepping with an irregular bird-like gait, lifting their knees high like storks. This undisguised joy in the strangeness of human activity in urban settings is what made Jacques Tati at his peak so beloved – a universally praised figure in French cinema when its nouvelle vague was represented by self-styled revolutionaries like Jean-Luc Godard.

After setting the scene in an automotive world Tati finally introduces Mr. Hulot, his most famous creation. This awkward everyman, an envoy from petit France as much as Father Brown or Captain Mainwaring represent "Little England", has managed to migrate from the technologically befuddled outsider status he'd occupied since Monsieur Hulot's Holiday (1953) to a position as draftsman and designer at Altra, a Parisian automaker whose latest product is a Hulot-designed camper kitted out with every modern convenience (albeit in the least expected places).

Hulot's task in Trafic is to get their camper through France and Belgium to the big auto show in Amsterdam, and at the last minute they get loaded up and set out in a convoy of three cars – the first a van loaded with most of their booth for the show as well as their salesman and owner, then the truck containing the camper and finally a little yellow 1967 Siata Spring driven by Maria, their fashionable American PR woman (played by American fashion model Maria Kimberly).

Hulot sets off in the Siata with Maria, a friend of the gadfly son of the company's owner, but moves to the truck when it has the first of a series of breakdowns just a few miles outside Paris. The owner and the salesman make it to Amsterdam in time to set up half their booth and spend the rest of the film waiting for Hulot, the truck, the camper and Maria.

Like all of Tati's films, there's not a lot to Trafic on paper. For not the first time he had dragged his feet before producing a written treatment to show his Swedish partners, and as Bellos wrote, only ended up showing them "an outline only six pages long, an untitled, unattributed and, frankly, rather scrappy piece of work."

The Altra camper is a callback to another Hulot vehicle, the decrepit Amilcar of Monsieur Hulot's Holiday, but the camper creation – built on a Renault 4L chassis – never hits the road and barely moves without being pushed. "It remains throughout no more than an idea of a car," writes Bellos, "a universal dream of a self-contained world that is nonetheless unmistakably French – the electric grill hidden beneath the front bumper is custom made for steak-frites ('with a garnish of loose chippings', quipped one reviewer) and the striped-canvas awning is just like the beach furniture of Les Vacances..."

We see ingenuity as characters adapt to the hours they spend in their vehicles; Maria's tiny yellow runabout can barely fit her luggage and her woolly little dog, Piton, so she stores her wide-brimmed sun hats in the compartment for the spare tire attached to the trunk.

After Tati created Hulot for his second film, the character and his subsequent films increasingly depict the man-child passively in conflict with a world modernizing far too quickly. The inference – and Tati never denied it – was that something human was being lost as the world became more like the assembly lines that were producing its consumer goods.

First there was the Villa Arpel, the impeccably modernist and wildly uncomfortable house of his sister and her husband in Mon Oncle, every gadget and surface designed to baffle or frustrate both its occupants and their visitors – none more so than Hulot himself, who lives in a tiny apartment built as an afterthought on the roof of a tenement building on the border of the Arpel's new suburb.

When Tati returned in Playtime that high modernist world had built itself over his shambling old one. Hulot is caught in the wake of a group of American tourists who arrive at the airport, before subsequent episodes in the plotless but rigorously structured picture take them all through offices, an apartment building, a restaurant and a trade exhibition, before the climax at the Carousel of Cars, every episode designed and choreographed by Tati to show Hulot lost while everyone around him risks creating chaos if they depart from the linear, robotic routine demanded by this new world.

Trafic begins where Playtime left off, but the Carousel of Cars has metastasized into a densely-packed parking lot full of new machines outside the auto factory. We watch these cars move from their pristine, parked state to the roads – the alimentary canal that digests these machines, sometimes with nibbles, sometimes with devouring jaws. As Hulot travels north in the truck bearing the precious Altra camper, he keeps passing garages and junkyards and ever-larger dumps of ruined and discarded vehicles.

It's not a subtle message, and it would be fair to say that the success of Trafic depends on how much of a light touch Tati has when painting his picture of this world on the other side of Playtime's gleaming but fragile modernism.

In Playtime we watched as nearly everyone but Hulot strained to live up to the precision demanded by a steel-and-glass world. It's a fantastic product of the post-war, pre-Beatles boom. In Trafic, a very '70s picture, it's all starting to break down, starting with the listless, unmotivated workers at the Altra plant, through to the Dutch border guards who impound the truck and the camper, citing improper paperwork.

(You wonder where these bureaucrats of the frontiers went with the dawn of the borderless European Union, but centralization demands ever larger armies of bureaucrats to regulate, threaten and enforce. What would Tati have done with this byzantine technocracy? I'm certain that our lack of a modern Tati drawing circles around its kaleidoscope of absurdities is one reason why it has persisted far longer than it should.)

Tati was born Jacques Tatischeff, and his family history was full of the broadly written drama he did his best to avoid in his own work. His grandfather was an aristocrat, a general in the Tsar's army and a military attaché at the Russian embassy in Paris when he fell in love with a French woman. They had a son out of wedlock and shortly after the general died in a suspicious horse-riding accident.

Their son was kidnapped by his Russian family but his mother taught herself Russian and got a job in Moscow as a nanny, where she managed to kidnap her child back again, returning to France and seeking obscurity outside Paris, in a small village she hoped would be out of reach of the rich and powerful Tatischeffs. Or at least that's the story Tati was told as a boy.

Tati's father did his best to become as perfectly average a Frenchman as he could, the dramatic high point of his life his time as a cavalry officer in the army during World War One. Jacques himself seemed to embrace the unremarkable as a poor student at school, a dullard and a dreamer who dropped out at sixteen to work at his father's framing business.

Bellos quotes Tati later saying that "Modern life is designed for the top boys in the class, and I would like to defend all the others."

Tati's one talent was for mimicry and physical comedy, which he ended up turning into an act as a mime in French music hall, to some acclaim. But he said that he was so depressed watching older performers dye their hair and rouge their cheeks to appear younger that he began looking for an escape from the stage, desperate not to be doing his old mime act pretending to box and play tennis as a senior citizen.

What he found were the movies, which were booming in France during the years between the wars. After the Second World War, during which he briefly fought as a cavalry officer, he directed and acted in a 1947 short film, L'École des Facteurs, playing a comically inept postman character he created. He'd build a whole feature, Jour de fete (1949), around the character, and the film was a great commercial and critical success just when the French film industry, now in decline, needed new geniuses.

Hulot was born with his second feature, Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot, the story of a beach holiday where nothing much happens beyond the spectacle of the bourgeoisie, petit and otherwise, attempting to enjoy their leisure. "Tati," Bellos writes, "sought to celebrate leisure, not work, 'time out' and not his time 'in'."

Hulot is never a conventional hero in Tati's stories; he reacts to things and people and never initiates action. If Trafic has a motivating character it's Maria, the American PR woman, who zips back and forth across the roads and through the action in her yellow Siata, changing her wardrobe and inadvertently putting new obstacles in the way of Hulot, the truck, its driver (Marcel Fraval) and the camper.

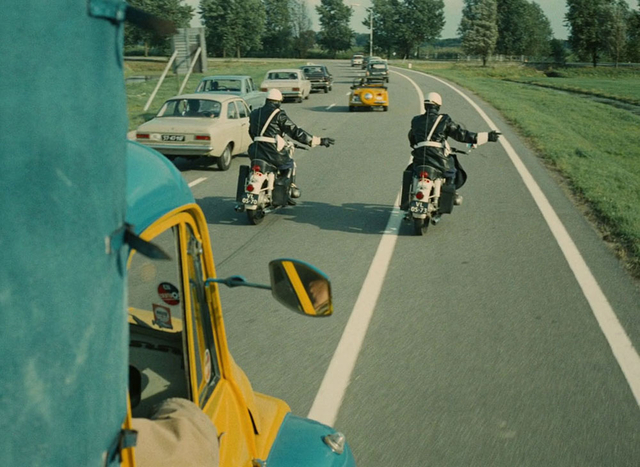

She's the reason they get impounded at the border, and it's her reckless driving that gets them into a massive traffic accident, a sequence that's the comic set piece of the movie. Trying to follow her as she speeds past a traffic cop at an intersection, the truck driver hits another vehicle, which sets a chain of collisions in action.

While the drivers remain mostly invisible behind the wheel, the cars take on personalities as they swerve, smash, careen and ricochet all over the road. One car is sent into an apparently endless spin, its tires digging a deep circle into the dirt, while a VW bug is forced off the road, the lid on its front boot snapping open and shut like the mouth of a Pac Man as it chases after a rolling hub cap.

The most futuristic car on European roads at the turn of the '70s was the Citroën DS, an engineering marvel with advanced hydraulic suspension that let it raise and lower automatically to deal with the indifferent state of French roads during its twenty-year production run. It was so advanced that service was famously nightmarish, and the few drivable examples left are either garage queens or museum exhibits, meant to be admired as objects, not machines.

Tati has a DS rise up on its front wheels as it brakes hard into the accident scene, but it was apparently easier to get the car to drive backwards on its front wheels so the shot was filmed backwards, with another car speeding past it in reverse, adding to the physically improbable chaos of the accident.

When every wrecked vehicle comes to a stop their drivers emerge and begin a ballet of stretching and twisting and bending as they check for injuries. A priest kneels at the back of his VW to tend to the engine, his motions copying the rite of the eucharist while a rolling hubcap mimics the sound of communion bells. Film buffs will recall that Godard had staged his own accident on the roadway for Weekend (1967); it's tempting to imagine that this was Tati's response to Godard's dogmatic nihilism.

The Altra truck and the camper inside are both damaged, which sends Hulot and Maria to the only garage they can find, in a sylvan spot by the side of a canal. The mechanic is competent but unhurried and by the time repairs are finished the Amsterdam auto show is over, and they arrive to find the owner sitting dejected by the remains of his booth, arguing with the organizer about the fees they paid for no apparent reason. Looking for someone to blame, the owner fires Hulot.

Tati's company went into receivership while he was making Trafic, and his Dutch partners pulled out when the money was gone, taking their cameraman and his equipment with him. Just at that point a Swedish TV crew arrived to film a documentary about the production; they were fans, and Tati convinced them to become his crew long enough to finish the picture.

Future director Lasse Hallström (My Life as a Dog, What's Eating Gilbert Grape, The Cider House Rules, Chocolat) was their cameraman until his youthful radicalism inspired him to speak too frankly with Tati during dinner one night. The director stormed out in a huff, leaving the Swedish crew to pay for the meal, and Hallström quit the picture. The crew's producer was given a quick overnight tutorial on operating the camera and shot the final day's footage with no protest from Tati.

Considering the film's troubled production history it's no surprise that Trafic has a slapdash, lurching feel that's either missing or minimal in Tati's best pictures. "For a film almost improvised as it was being shot," Bellos writes, "Trafic has a fairly clear and firm plot, and one which, in an obvious sense, also tells the story of the film's own making, and of the filmmaker's own fundamental flaw: his inability to do things on time."

Trafic opened in a cinema on the Champs-Elysées in April of 1971; a Renault showroom across the street put the Altra camper from the film on display in its front window. It got a mixed reception from critics, the most favourable reviews conceding that at least it was better than Playtime.

Bellos writes in his book that the "vaguely left-wing Nouvel Observateur thought the film ideologically suspect: its critique of motorcar culture was not harsh enough, it said, and its gentle comedy was more likely to reconcile people to cars than to make them give up on driving."

Tati would make one more feature, Parade (1974), for Swedish television, produced by the same man who had been pressed into service as cameraman for the last day of filming on Trafic. It was a tribute to old-fashioned circus performers – a variety show that featured Tati himself, not as Hulot, but doing his old music hall act, miming boxers and tennis players in his late sixties, just as he had feared he would as a young man. He died of cancer in Paris in 1982, just in time to see his reputation rehabilitate him from a commercial failure to an artistic success.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.