The American West was a myth even while it was still being settled, so it's not surprising that western movies were always understood as fantasies, whether they were shot on a soundstage or on a dusty, sun-baked location, with cowboys in shiny spurs and embroidered shirts or covered in the filth of the trail.

"There's something fantasy-like about an individual fighting the elements," as Clint Eastwood said. "Or even bad guys and the elements. It's a simpler time. There's no organized laws and stuff."

In their book The Western From the Silents to the Seventies, George Fenin and William K. Everson call the western a "state of mind" and write that "the frontier is, in fact, the only mythological tissue available to this young nation. Gods and demigods, passions and ideals, the fatality of events, the sadness and glory of death, the struggle of good and evil – all these themes of the western myth constitute an ideal ground for a liaison and a re-elaboration of the Olympian world, a refreshing symbiotic relationship of Hellenic thought and Yankee dynamism."

Which is a mouthful, to be sure, but it helps explain why the movie genre closest to the western is science fiction. There's a case to be made that both genres can't share a resurgence at the box office; basically you never see them together in the same room. And it's why the best westerns can feel like a dream, though not necessarily a good one.

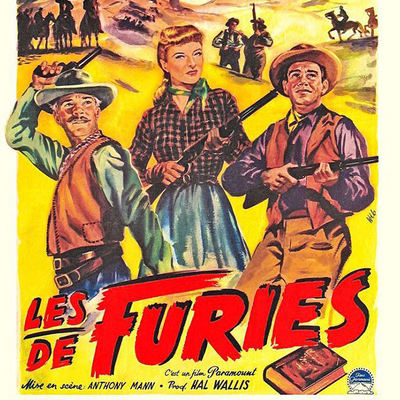

The Furies (1950) is a western whose title comes from Hellenic myths – an inspiration for Fenin and Everson's theoretical musing, no doubt – and whose plot has been described as Freudian, about a woman with an Electra complex (those Greeks again!) set on a vast, dusty ranch in the New Mexico Territory.

T.C. Jeffords (Walter Huston) is the owner of The Furies, a spread that runs from horizon to horizon where he's the lord and the law. The first person we meet onscreen is his son Clay (John Bromfield), who sees a light on in his late mother's room as he rides back to the family hacienda. The room has been preserved as it was when his mother died, but he finds his sister Vance (Barbara Stanwyck) there, wearing her mother's dress and jewels as she prepares for their father to come home.

Quick dialogue between the siblings establishes that while he might be T.C.'s son, Vance is the heir, a woman of immense will, proud that her father has never beaten her; whether physically or emotionally isn't specified and doesn't seem to matter. Male primogeniture has been suspended in this wild place, though Clay doesn't seem terribly bothered about it. He's the least tightly-wound character in the whole picture, and after his imminent wedding to the daughter of another big rancher he effectively disappears from the story.

When T.C. arrives home from San Francisco, he's brought along a banker from the big city, a representative from the Anaheim Bank, who he's asked to advance him a hundred thousand dollars. The old man introduces the banker to his family and his household, which includes his accountant Scotty (Wallace Ford), a convicted embezzler, and El Tigre (Thomas Gomez), his sinister ranch whip hand, a onetime hero of the Mexican Revolution who fled the country when he got too fond of hanging men.

T.C. is a huge admirer of Napoleon Bonaparte and so much a law unto himself that he's his own bank, issuing printed I.O.U.s emblazoned with a Latin motto and the picture of a girl riding a bull – his own currency, which he's dubbed "TCs". Clay brings them up inopportunely when his father is negotiating with the banker, though their existence doesn't seem to bother him as much as the squatters that have made their homes on The Furies.

The banker is going to deny the loan after T.C. accedes to Vance's insistence that one family, the Herreras, are not to be evicted, but the old man plays the card he's had up his sleeve and blackmails the banker, who fell into the honey trap T.C. set for him with Chiquita (Movita Castaneda), his housekeeper.

It goes without saying that T.C. has made a lot of enemies, among them the Herreras, who lived on the land before he arrived. The other is Rip Darrow (Wendell Corey), whose father was cheated out of his ranch, now the best part of The Furies, before being killed by T.C. in a duel. He's a professional gambler who runs the Legal Tender, a saloon and casino in the nearby town, and gatecrashes Clay's wedding celebration, defying the old man and catching the eye of Vance.

Rip and Vance have a brief romance despite T.C.'s disapproval, but he makes a bet with her that Rip is more interested in his money than her. He wins the bet when he offers the gambler half of the money he got from the bank – money that he was going to give to Vance along with her chance to run The Furies – to leave the ranch and never come back.

Rip tries to explain to Vance that his feelings for her had nothing to do with wanting to get compensated for what T.C. took from him, but she's still furious, so he takes the money and starts his own bank, its offices overlooking his casino floor, and even gets himself appointed as local agent for the Anaheim Bank.

Rip is just one point on the romantic triangle the wilful Vance is part of, the other being Juan Herrera (Gilbert Roland), oldest son of the squatter family that have built themselves a fortified clifftop homestead on The Furies. Vance and Juan are childhood friends, and their relationship has developed into something more ardent, though neither of them are under any illusions that it's worth pursuing under current circumstances.

But the triangle is really a square, the fourth corner being T.C. himself, with whom Vance has an unquestionably intimate, more than vaguely sexualized relationship. His daughter seems to be the only person, male or female, that the old man admires, his echo in flesh and blood, and he frequently asks her to scratch an old arrow wound on his back for relief. Even if you'd never heard of Freud your eyebrows would be raised by the scenes Stanwyck and Huston share.

On paper The Furies is pretty hot stuff, though Anthony Mann's stark direction and Victor Milner's stygian camerawork takes it to an austere place – more like the psychological drama King Vidor tried to make with Duel in the Sun (1946) before producer David O. Selznick took over and turned it into an infamously hypertrophied, heavy-breathing epic.

This isn't terribly surprising since both movies are based on books by novelist and screenwriter (The Postman Always Rings Twice, Pursued, Distant Drums) Niven Busch at the height of his career, whose wife at the time was actress Teresa Wright. Charles Schnee's screenplay takes the usual gang of liberties with the book, but the relationship between Vance and her father is there, in plain sight, in scenes like the one where Vance scratches her father's old wound, in the cartilage by his sixth lumbar vertebra:

"Vance had seen her mother do it too and now, almost without thinking, she put her hand up and rubbed her father's back. T.C. closed his eyes with enjoyment; then he nodded and patted her knee as if such intimacy between them were an everyday occurrence."

The Furies was made at a crucial point in director Anthony Mann's career. He had gone from theatre in New York to working for Selznick as a talent scout and casting director, shooting and editing screen tests. (The first actress he tested was Jennifer Jones, who became Selznick's longtime mistress and wife.) His first film, Dr. Broadway (1942), was inauspicious, and it was the first of a series of cheapies he produced on time and on budget before his first hit: the police noir T-Men (1947), made for Eagle-Lion, a British-American company that briefly took up residence on Poverty Row.

He went on to make Desperate (1947) for RKO and Raw Deal (1948) and Reign of Terror (1949) for Eagle-Lion, then got an offer to direct Devil's Doorway (1950), his first western, about a Shoshone native and Civil War hero played by Robert Taylor who become a victim of bigotry when he returns home. This led to a phone call from an old friend from the New York theatre scene, James Stewart, who asked if he was available to direct Winchester '73 after Fritz Lang had dropped out.

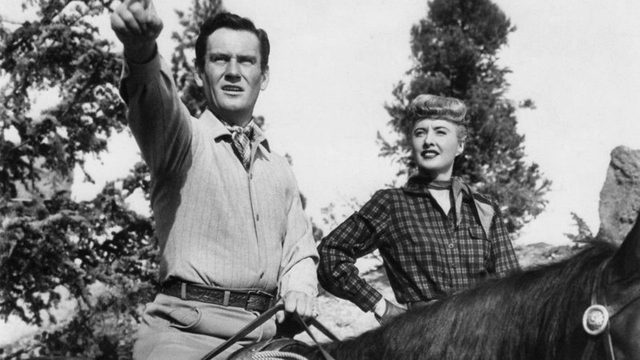

The actor and director teamed up for eight films, of which the westerns (including Bend of the River, The Naked Spur, The Far Country and The Man from Laramie) are considered classics, the non-westerns (Thunder Bay, The Glenn Miller Story, Strategic Air Command) less so.

The Mann-Stewart westerns are often prominent on lists of westerns that moved the genre on from franchised oaters, b-pictures and serials to more adult pictures made by major studios in the '50s – movies made by filmmakers (like Mann) who idolized John Ford, clearing the ground for Italy's spaghetti westerns and the morally unmoored new westerns of the late '60s and early '70s like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Jeremiah Johnson and High Plains Drifter.

These pictures are notable for sudden explosions of violence and a less-than-charitable take on men's motivations when they are beyond the reach of law and civilization. Stewart's characters go through a lot of physical punishment, enduring grievous wounds like a bullet through his hand from his own gun in The Man from Laramie. And they're usually driven by revenge: in Winchester '73 he wants to kill his own brother for murdering their father.

Mann favoured Shakespearean stories, and The Furies was first of his several attempts to remake King Lear as a western. (He would try again in The Man from Laramie and Man of the West (1958), and despite getting closest with the latter, he was still planning one more shot with a picture to be titled The King when he died suddenly on location in Berlin in 1967.)

While T.C. is obviously Lear, Clay is no Cordelia, so Stanwyck's Vance becomes a combination of the good daughter and the bad ones. It's hard to imagine anyone else in the role; by this point in her career Stanwyck had made a specialty of troubled, wilful, difficult, defiant women who evolved out of the tough broads and femme fatales of her earlier career, in films like The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946), The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947), Sorry, Wrong Number (1948) and East Side, West Side (1949). Her role in Sam Fuller's Forty Guns (1957) would be a reprise of Vance Jeffords, as was Victoria Barkley in the TV series The Big Valley.

You could say that Stanwyck was busy creating a role that nobody else could play. As critic Robin Wood wrote in an essay included with Criterion's deluxe edition of the movie, "by the time in her career when she was making The Furies she scarcely needed a director, and despite Huston's splendid quasi Lear, she is the film's centre, a miscast Wendell Cory giving little challenge."

Despite her strengths Vance can't control the men in her orbit, her father least of all, and T.C. returns from San Francisco again, this time with a well-connected widow, Flo Burnett (Judith Anderson), who sets about forcing a wedge between Vance and her father. The old man gifts Flo the other half of his loan money from the bank, then announces that they'll be getting married in San Francisco, after which a hired man will take over running The Furies while Vance is sent on a grand tour of Europe to get some civilization.

This is more than Vance can stand, and she hurls a long pair of scissors from her mother's dressing table at Flo, scarring and paralysing the older woman's face. She flees to the Herreras for refuge while her father sets out with a posse to bring her back and get rid of the squatters once and for all. "She's a cancer to be cut out!" the old man bellows.

While the Herreras hold off T.C. and his men with battlements and boulders, Juan stops his marksman mother (Blanche Yurka) from picking off T.C. and agrees to surrender and leave The Furies forever. T.C. is willing to forgive the squatting, but not his theft of one of his horses; he tells El Tigre to hang Juan, who calmly walks to the noose knowing his death is the one thing that might snap the bond between Vance and her father.

Vance sets off on a journey of revenge, traveling all over the southwest and to San Francisco, buying up the TCs her father has strewn all over the country for pennies on the dollar. She even joins forces with Rip, who's just as eager to get revenge on T.C. but tells her that she's becoming monstrous in her anger, that "You're in love with hate."

The audience should, by this point, be fully on the side of Vance except that Mann lets Huston play T.C. as the only person in the picture who thoroughly enjoys being himself, with an almost indecent enthusiasm that Huston was built to portray. Unaware of his daughter's plan, he's in desperate straits when the bank calls in his loan; he asks if Flo will give back the money he gifted her, but the now-scarred woman tells him that if she's going to be alone from now on – she knows T.C. will leave her whether he saves his ranch or not – she'd rather be alone with the comfort of money.

The old man can't deny the wisdom of her position and toasts her before heading back to The Furies for one big round-up of all the cattle he can sell, unaware that even this last chance is a trap set by Vance and Rip. Mann indulges the character and lets Huston show off; the old man pulls off the herculean feat, almost falling asleep in the saddle during day-long cattle drives, then roping a rogue bull that had the audacity to be nicknamed The King; there will only be one King in The Furies, and T.C.'s legend is assured when one of the cowboys sings a song about him that's been going around.

And when he arrives at Rip's bank to discover that his daughter is the buyer for his cattle and is paying him with a box stuffed with worthless TCs, he admits defeat with a laugh, as if this humiliation was a test to see if she was worthy of The Furies. This takes the sharp edge out of Vance's revenge – but not out of Herrera's marksman mother's as she waits in ambush for T.C.

Endings are rarely satisfying, especially here as Mann and Schnee lose their nerve and leave Vance and Rip with a hollow and unconvincing hint that they have a future together despite all that's happened. The credits should have rolled a scant minute earlier, on a tragic scene that the film had nonetheless earned.

Huston's last line in the movie is "There will never be another one like me." Walter Huston died in his Beverly Hills hotel in April of 1950, three months before The Furies was released. The picture made $1.5 million at the box office but was still called a failure by Paramount. It lost to Carol Reed's The Third Man for best cinematography at the 1951 Oscars – a picture that didn't flinch when delivering its bleak ending.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.