Nobody does political cynicism like the Italians. As a country it hasn't been crucial since the fifth century AD, but it knows more about how politics works – and more importantly how it doesn't work – than any other nation on the planet.

After refining Greek democracy into a workable system for a growing empire, Rome set about discovering all the ways government could corrupt itself, then descended into over a millennia of decline and division. The moment – brief, hopeful and doomed – when Italy struggled to reemerge as a national entity again is the setting for this week's movie, a remarkably intimate historical epic that flopped when it was released in North America.

Italians are both blessed and cursed with the certain knowledge that every law, proclamation, edict or speech issued by government is designed to obscure what government actually does from the citizen. As Luigi Barzini, author of The Italians said:

"Foreign diplomats in Rome disconsolately say, Italy is the opposite of Russia. In Moscow nothing is known, yet everything is clear. In Rome everything is public, there are no secrets, everybody talks, things are at times flamboyantly enacted, yet one understands nothing."

In 1954 a Sicilian aristocrat named Guiseppe Tomasi de Lampedusa (11th Prince of Lampedusa, 12th Duke of Palma) attempted to save himself from penury by writing a novel that would become a massive bestseller – though sadly not until a year after Lampedusa died. It wasn't long before another Italian aristocrat, Luchino Visconti de Modrone (Count of Lonate Pozzolo), took on the job of turning Lampedusa's book, The Leopard, into a movie, with backing from Titanus, an Italian studio, and an American one – 20th Century Fox.

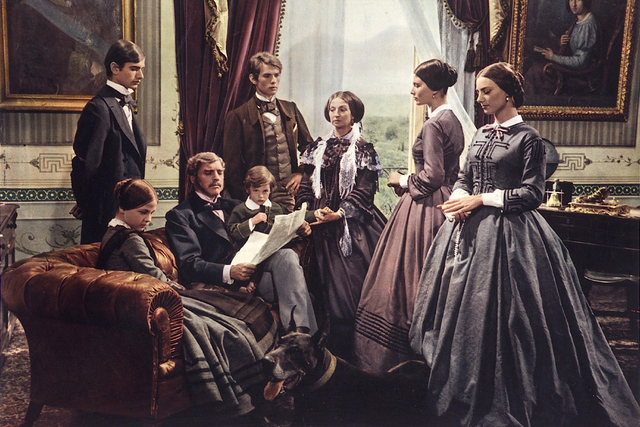

The film, released in 1963, begins as any historical epic should, with a widescreen camera slowly entering the gates of a sun-baked estate, tracking toward the great house along a dusty avenue lined with trees and weathered sculptures. The camera rests on the terrace, with its empty chairs and a table, before Nino Rota's soundtrack slowly fades to the sound of voices praying the rosary.

We resume floating through the hot air and afternoon light to a window, and a room where the family of Don Fabrizio Corbera, Prince of Salina (Burt Lancaster) kneel along with their household – a governess and a tutor and a collection of liveried servants – while the Corbera's chaplain, Father Pirrone (Romolo Valli) leads the prayers.

Shouting slowly builds in the background, but as long as the Prince remains kneeling nobody but a single servant has the nerve to get up and find out what's happening. When prayers finally end – at the moment Don Fabrizio decides, not Father Pirrone – we learn that a dead soldier has been discovered among the olive trees on the estate, an early casualty of the invasion of Sicily by Guiseppe Garibaldi and his army of republican Redshirts, intent on overthrowing Sicily's Bourbon king.

Garibaldi, a romantic hero, an Italian nationalist (though he was born in Nice) and a veteran of several forgotten wars in South America, was the essential figure, the military victor and ultimately the most notable victim of the Risorgimento – a conflict that reached its climax at the same time as the early years of the American Civil War.

Italy had been a collection of kingdoms, duchies, principalities, republics, Papal territories and city-states since the fall of the Western Roman Empire, invaded and conquered incessantly and usually run by foreign kings. Individual cities and regions in the north might have risen to wealth and prominence but the rural south was famously poor and backward – places like Sicily, where the Corberas are still wealthy and venerable under the rule of a weak Bourbon king, supported half-heartedly by the British.

Garibaldi's revolution, so long coming, has finally arrived – news that the Prince takes impassively while it sends his wife Maria (Rina Morelli) into hysterics. In any case no dead soldier or army of red-shirted fanatics will stop him from taking his coach – with Father Pirrone as an unwilling companion – into Palermo for a visit to his mistress.

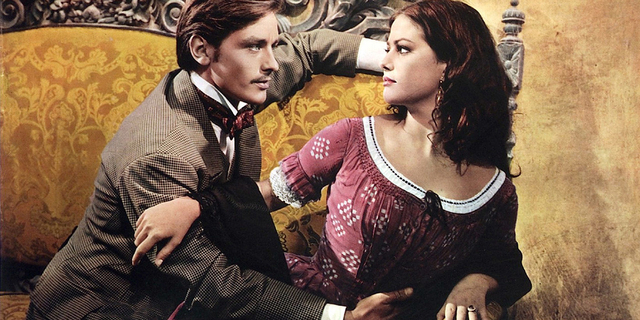

The next morning, as he shaves and ignores the priest's pleas that he confess his sins of the previous night, the Prince is joined by his nephew, Prince Tancredi Falconeri (Alain Delon). Tancredi is an orphan, the son of his late sister and her dissolute husband, whose family might be even more illustrious than the Corberas, though their fortune is long gone.

Tancredi is the Prince's favourite, more beloved than his own sons, which Visconti makes us understand when our first glimpse of Delon's face is in the Prince's shaving mirror. He's handsome and charming and has taken to idly toying with the affections of Concetta (Lucilla Morlacchi), the oldest Corbera daughter. And he's come to tell his uncle that he's off to join the Garibaldini in the mountains and help overthrow the Bourbon king.

The Prince is certain that despite all the shooting and fighting, nothing is really happening in Sicily except the slow replacement of the aristocracy by the middle class, for whom Garibaldi is simply a tool to accelerate their seizure of power and privilege. Tancredi's enthusiasm for Garibaldi might look like a young man's impulsive political idealism, but he tells his uncle that it's necessary if their class is going to survive.

"For things to stay the same," he tells his uncle, "everything must change."

When Luchino Visconti took on adapting The Leopard into a movie, his first choice for Don Fabrizio was Nikolay Cherkasov, the Russian actor who had played the protagonists of Sergei Eisenstein's Alexander Nevsky (1938) and Ivan the Terrible, Parts 1 & 2 (1944 and 1957), and his second choice was Laurence Olivier, who was unavailable due to either health or scheduling conflicts.

The casting of Burt Lancaster as the Prince was forced upon him by the film's producers, who needed a major star to guarantee financing. He was shocked by the choice of Lancaster, who he called an "American gangster"; the standouts among his most recent roles had been in Gunfight at the O.K. Corral and Sweet Smell of Success (1957), Run Silent, Run Deep (1958), The Unforgiven and Elmer Gantry (1960) and Judgment at Nuremberg (1961). His reaction spread through the rest of the production, so when Lancaster arrived in Italy for rehearsals he was met coldly; the director was particularly dismissive when he asked the actor to go through a scene where he had to waltz with Claudia Cardinale.

But Lancaster was a quick study, and he quickly overcame Visconti's doubts so much that the men became lifelong friends. The director went so far as to help Lancaster's research by rounding up a handful of Sicilian aristocrats still alive at the time (Lampedusa's death would have been a considerable obstacle) but in the end Lancaster decided that the best model for an aristocratic hero was the one he had in front of him every day – Visconti himself.

It's hard to imagine anyone else but Lancaster as the Prince now – even though the best version of the movie (the longer one released in Europe) is dubbed like every Italian film, with the voice of Corrado Gaipa coming out of Lancaster's mouth. (Gaipa would dub the voice of Obi-Wan Kenobi for the Italian release of the original Star Wars trilogy, Bagheera in The Jungle Book, Spencer Tracy in Guess Who's Coming to Dinner and Rod Steiger in In the Heat of the Night, among many other pictures.)

As Lampedusa makes plain in his novel, the Prince is a powerful, virile man, full of masculine energy that enhances his hobby as an accomplished amateur astronomist. It's the sort of role that the athletic Lancaster loved to play in films like The Crimson Pirate and The Swimmer, but he relaxes into Don Fabrizio, conveying his strength through elegance and economy of gesture – a stillness that stands out in the context of an Italian cast given to emoting with their hands.

Don Fabrizio keeps a mistress because his devout wife crosses herself every time he kisses her and, as he complains to Father Pirrone, they have had seven children "but I've never seen her navel!" ("She's the sinner!" he bellows at the priest.) He's only 45 when the movie starts but feels life moving fast and is given to persistent, morbid thoughts.

The first scenes Visconti filmed when cameras rolled was the battle between the Garibaldini and Bourbon soldiers in the rubble of Palermo, where Delon's Tancredi earns a minor wound that allows him to wear a dashing eyepatch for the next few scenes. There are no battle scenes in Lampedusa's novel, but Visconti knew that he had to deliver an action scene to justify marketing the film as an epic.

Master cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno (White Nights, Fellini Satyricon, Carnal Knowledge, Amarcord, All That Jazz, Popeye, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen) obliged with lavish widescreen compositions that look like paintings from the Italian impressionist Macchiaioli movement contemporary with the film's setting, or Gerolamo Induno's canvases of battles.

But no revolution will stop Don Fabrizio from taking his family on their annual summer retreat to their country seat at Donnafugata, where they live in the remnants of feudal splendour, in a grand house that dominates the town square more than the adjacent church. Visconti shows them making their slow procession through the countryside, Tancredi on horseback bullying his way through the Redshirt checkpoints, ending up in the place of honour at the front of the church for a celebratory mass, where Rotunno's camera pans slowly across the family covered in dust from the road, looking like beautifully preserved mummies.

But the future has arrived even in Donnafugata, in the shape of Don Calogera Sedara (Paolo Stoppa), the town's "big man" whose role as comic relief in the story in no way undermines his sinister capabilities. Sedara has been busy making himself essential to the new regime during the revolution, and thanks to careful but quiet acquisition of properties such as those confiscated from the Catholic church, is now as rich or richer than the Prince.

His newfound power is revealed in a mostly comic scene where he presides over the October 1860 plebiscite where Sicily was asked to decide to join the new Kingdom of Italy under the Savoyard Victor Emmanuel II. He's interrupted by the town's marching band repeatedly while trying to announce the results, which everyone knows to be a fraud: of 515 eligible voters, 512 voted yes to unification, unanimously.

Don Fabrizio has only two men in whom he can confide, one being Father Pirrone and the other Don Ciccio (Serge Reggiani), the organist at Donnafugata's church and the Prince's regular hunting companion. Both men are from humble or reduced circumstances, and both are recipients, directly or indirectly, of the Prince's patronage.

In the hills above the town after the plebiscite Don Ciccio rages about watching helplessly while Sedara and his cohort stole his vote. "I said black and they made me say white," he tells the Prince, who had made a very public show of voting for Sicily's annexation into the new Kingdom; he has taken to heart Tancredi's insistence that "everything must change" if he and his class are to survive.

But the most visible symbol of change in Sicily isn't Sedara but his daughter Angelica (Cardinale), a ravishing beauty who catches the eye of both Tancredi and the Prince when her father introduces her at a dinner the Corberas hold to celebrate the plebiscite.

By this point Tancredi has returned again, swapping his red shirt for the uniform of an officer in the new army of the Kingdom of Italy. The Prince wryly notes the change, but Tancredi tells him that it was essential to separate himself from the "rabble" surrounding Garibaldi, who were only good for looting and rape.

The Princess is outraged at Tancredi for betraying Concetta, but her husband reminds her that with his fortune split seven ways for dowries and patrimonies, the girl wouldn't have near enough money to support Tancredi in what everyone knows will be a brilliant career, even if she wasn't so painfully shy and awkward.

Angelica, on the other hand, will bring her beauty and the full force of Sedara's fortune, which he will be happy to spend to advance his family further in the new regime – which has turned out to be another monarchy and not the people's republic imagined by men like Garibaldi. At the end of the negotiations between Sedara and the Prince, Lancaster walks around his desk and picks up the little man from his chair, holding him in the air while he kisses his cheeks – then turning to grimace after he puts him down.

The Leopard plays out in three sections: a short early one to introduce the family and the history, the second at Donnafugata, which ends when the Prince is visited by Cavalier Chevalley (Leslie French). He's a nobleman from the north and a representative of the Savoyard regime who were the real winners of the Risorgimento which, once you sweep aside the dynasties and factions, was really just about the industrial north annexing the rural south to give Italy the heft and legitimacy to give it agency in the coming European power plays – a nationalist entity big enough to join the alliances of more powerful nations.

Chevalley is terrified to be in Sicily, with its reputation for banditry and barbarism – a reputation that the younger members of the family do nothing to dispel. But he's there to offer the Prince a seat in the new Italian Senate – a sign that the new regime is just a supersized version of the old one, after the turmoil in which "everything must change."

Lampedusa was a monarchist, and considered a reactionary in Italian politics, while Visconti was a self-proclaimed communist. (At one point Italy was as full of titled communists as self-made men.) But both men had so much common ground that the scene between the Prince and Chevalley echoes nearly perfectly from the book to the movie.

Visconti pointedly had French's Chevalley made to look as much like the statesman Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour – a major player in the Risorgimento alongside Garibaldi and the republican agitator Giuseppe Mazzini. (Lancaster's Prince calls Sedara the "Cavour of Donnafugata" when he sees him presiding over the plebiscite ballot box.) Chevalley tells the Prince that this is a chance to bring Sicily into the modern world, to banish the poverty and backwardness for which it was infamous.

Don Fabrizio responds that this would probably be a good thing, but that he thinks Sicilians would resent this since, despite all their suffering, they considered themselves perfect, with an ancient history that made them all, prince to peasant, the equivalents of gods on the earth. Theirs is a culture that longs for death, and all they ask of the world is that it lets them go back to sleep.

As for himself, he doubts that he would be much use to the new government and their idealistic plans for this new Italy. "What would the Senate do with an inexperienced legislator who lacks the faculty for self-deception, essential requisite for those who wish to guide others?" He recommends that the Chevalley consider Don Calogera Sedara for their new government.

"His family, I am told, is an old one or soon will be," the Prince tells Chevalley in the novel, in a speech Visconti duplicates in his movie. "He has more than what you call prestige, he has power; he has outstanding practical merits instead of scientific ones; his attitude during the May crisis was not so much irreproachable as actively useful; as to illusions, I don't think he has any more than I have, but he's clever enough to know how to create them when needed. He's the man for you."

I have never read a paragraph that sums up the political beast more perfectly.

The final section of the movie is a grand ball held in Palermo, held in honour of Colonel Pallavicino, the hero of the Battle of Aspromonte – actually a ten-minute skirmish in the summer of 1862 that left Garibaldi wounded and finished off the Redshirts. It's meant as Angelica's debut in society before her marriage to Tancredi, and it's based on the balls that Lampedusa and Visconti had watched through the stairs of their parents' homes when they were children.

It's long – pointedly, aggressively long, and it was cut extensively for the version of the picture that director Sydney Pollack helped edit (to his everlasting regret) for The Leopard's U.S. release. This was the version that flopped upon release despite Visconti winning the Palm d'Or at Cannes, and it's available on the Criterion edition of the picture, though I have never seen it. I first saw The Leopard when the restored European cut was rereleased in theatres in 1983, and it's still one of my favorite films of all time.

The ball is the beginning of the Prince's decline; he wanders the rooms full of grasping nouveau riche like Sedara and notes with dismay that the custom of marrying cousins has not done much for the young women jumping all over the pouffes and settees. In Lampedusa's novel Don Fabrizio wonders that they look like "a hundred female monkeys; he expected at any moment to see them clamber up the chandeliers and hang there by their tails, swinging to and fro, showing off their behinds and loosing a stream of nuts, shrieks and grins at pacific visitors below."

He's particularly annoyed by Col. Pallavicino, a bore who endlessly re-tells the story of accepting the surrender of the wounded Garibaldi, claiming that the old soldier had quietly thanked him for freeing him of his fanatic followers.

He finds refuge for a while in the host's library, where he's transfixed by a painting of a man on his deathbed, surrounded by his family, and wonders if his death will look like this. He's joined by Tancredi and Angelica, who asks him if he'll dance with her – a flattering gesture to the old man, but also a spectacle sure to cement the social significance of her debut.

He joins her in a waltz, showing off his famous skill as a dancer, but when it's over he feels the weight of age and death press down on him again. At one point he stares at himself mournfully in the mirror of a gentleman's lounge, before discovering the adjacent room full of brimming chamber pots.

When I first saw The Leopard I wasn't quite twenty years old, and found the overwhelming sadness of the ball scene disconcerting after marvelling at the virility of Lancaster's Prince; today I watch it feeling every ounce of the weight of age pressing down on Don Fabrizio and wonder at how well Lancaster plays a man's helpless realization that whatever comes next, death comes after that.

As dawn breaks Tancredi notes that the men who deserted the army to rejoin Garibaldi, his former comrades-in-arms, are to die by firing squad that morning, and remarks that it's best for everyone – a callous pragmatism that even Angelica finds shocking and echoes the Prince's intimation that despite his charm there was something "ignoble" about Tancredi.

Not long afterwards the Colonel and his fellow officers take their leave to head back to the barracks and a final duty that awaits them there. In the coach where Angelica sleeps on Tancredi's shoulder while her father sits yawning across from them, they hear a volley of gunfire.

"Just what was needed for Sicily," Sedara tells them. "We can rest easy now."

They're the final words in the picture.

Even though The Leopard flopped badly in the U.S. and it bankrupted its Italian producer, its reputation lingered long enough to justify the 1983 rerelease, and today it's considered not just Visconti's masterpiece but a landmark in Italian cinema.

It was so revered that Bernardo Bertolluci was inspired in 1976 to make a sequel of sorts, 1900, which featured not just Romolo Valli but Burt Lancaster playing a degraded update of Don Fabrizio, a wealthy landowner and father to Robert De Niro's character. It's a picture that feels both epic and sordid – a young man's bitter rebuke to a film he knows he could never make.

And now this year promises the release of a Netflix miniseries adaptation of The Leopard, marketed to fill the niche created by titles like The Crown. A Variety story notes that it stars Monica Belluci's daughter Deva Cassel as Angelica, and that it's both a period picture and an "update" on the original story, so you can't help but wonder if it will include the final chapters of Lampedusa's novel, cut by Visconti from his story.

They gave the story a melancholy finale with the Prince's death, Tancredi's disappointing fate, and the spinster Concetta and her sisters squandering much of what was left of the family fortune on bogus holy relics. The only certainty is that Netflix had no chance filling Lancaster's shoes, and that might doom it from the start.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.