Billy Wilder didn't think much of The Spirit of St. Louis. Filming on his 1957 movie about the landmark transatlantic flight by Charles Lindbergh had not been easy – Wilder called it "horrendous," complaining about the constant delays due to weather, adding that "I never should have made this picture."

It's a film that looks like nothing else in Wilder's filmography; I'm constantly surprised when I remember that he was the director. Looking back, Wilder judged it a failure mostly because "I wasn't able to depict the character," adding that "I should confine myself to bedrooms maybe."

He made it between The Seven Year Itch (1955) and Love in the Afternoon (1957) – two far more typically Wilderian pictures, though even fans might admit that they weren't really among his best. You can place it in the middle of a relative lull in his career, which began after Sabrina (1954) and ended with Some Like it Hot (1959).

What shocked me as a Wilder fan was that, after avoiding the film for years thanks to its poor reputation and the director's own dismissal, it isn't that bad. Though you really need to squint hard to see Wilder at all in its two-hour-plus runtime.

The film was based on Lindbergh's own bestselling memoir, The Spirit of St. Louis, winner of a Pulitzer Prize in 1954 – a book that explores his 33-hour nonstop solo flight from Long Island to Paris in excruciating detail over its 500 pages. Wilder was a man who preferred Mitteleuropean sex comedies as source material for his pictures, so you have to assume that he took the job for the usual reason: money. It was, after all, expensive to be Billy Wilder.

He didn't even have his usual collaborators on the script. His partnership with Charles Brackett had ended with Sunset Boulevard (1950) and he would flirt with different screenwriting partners for much of the subsequent decade until he started working with I.A.L. "Izzy" Diamond on Love in the Afternoon.

The Spirit of St. Louis was really producer Leland Hayward's picture, and Wilder's first writing partner on the project was Charles Lederer, who joined the long list of people who found working with the acerbic, high-strung Wilder impossible and quit. His vacant chair was taken by Wendell Mayes, who had, as Ed Sikov writes in On Sunset Boulevard: The Life and Times of Billy Wilder, "never written a film, never been in Hollywood, never heard of Billy Wilder."

Unlike Lederer, though, Mayes let Wilder's relentless sarcasm and insults slide off his back. "Funny that Lederer was great at writing screwball comedies," Sikov wrote, "but found living on unbearable, while Wendell Mayes fell into the constant joke routine with all the self-assurance of Myrna Loy standing up to William Powell."

The film the three men eventually wrote begins in a Long Island hotel where newspapermen have taken over the lobby, with desks and typewriters and telephones with direct lines to their newspapers and wire services strung from the ceiling. Their quarry is Lindbergh, the 25-year-old air mail flyer who they hadn't heard of a week earlier and have now turned into a celebrity, with nicknames like "Lucky Charlie," "Lone Eagle" and "The Flying Fool."

Lindbergh (Jimmy Stewart) is upstairs trying to sleep while he and his plane are grounded by bad weather. His mind flashes back to flying air mail routes across the Midwest in sleet and snow, parachuting from his biplane when it runs out of fuel in a storm and ending up completing his journey to Chicago by train.

He meets a stalwart representative of American Babbittry – a jocular suspender salesman who ribs him about the danger and improbability of making a business out of airplanes. But Lindbergh has a vision, of commercial aviation knitting the world together at speed, and sees an opportunity to prove this when French-born hotel mogul Raymond Orteig offers a $25,000 prize to the first man or team that can fly across the Atlantic from New York to Paris without stopping or refueling.

He gets backing from a group of St. Louis businessmen who hope the publicity will see the city established as a vital aviation hub. But Lindbergh meets his first setback when he travels to Manhattan and the Woolworth Building offices of the Wright Aviation company to buy a plane, and gets turned down when the company insists on picking the pilot – which will not be some gawky veteran of struggling air mail routes and barnstorming flying circuses.

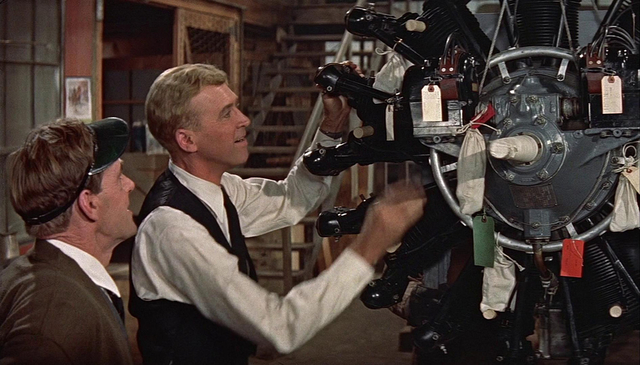

But his backers send him to Ryan Airlines, a struggling plane builder in San Diego, which Wilder depicts like a sleepy Mexican border town, the Ryan company a shoestring operation run out of a rickety hangar, where a shaggy dog sleeps on the factory floor and the owner cooks lunch on a piece of scrap iron with an acetylene torch. The Spirit of St. Louis is very much an American story, where underdogs like Ryan and Lindbergh are more inherently heroic than arrogant corporations in skyscrapers, so the pilot moves into the factory and helps design the plane that is supposed to take him across the Atlantic.

By the time the plane is finished four men have died attempting to win the Orteig prize, and when Lindbergh takes off from San Diego for St. Louis another two – Charles Nungesser and François Coli, both more famous and experienced than Lindbergh – have left France for New York, though by the time Lindbergh lands their plane has been lost and neither man would be seen again.

Lindbergh and Ryan Airlines owner Frank Mahoney (Bartlett Robinson) and designer Donald A. Hall (Arthur Space) have been ruthless about shaving every ounce of weight off their plane, with Lindbergh even opting to fly without a radio or parachute so The Spirit of St. Louis can carry more fuel. Wilder's film is commendable for sticking as closely as possible to Lindbergh's memoir, but it pauses in the hangar on Long Island for the first of a handful of significant inventions.

It must have bothered the producers of The Spirit of St. Louis that Lindbergh's story has no love interest. (The flyer lived a rather monastic life until he became world famous and he wouldn't meet his wife, the poet Anne Morrow, until seven months after his famous flight, though he later fathered seven illegitimate children with three German women.) This led to the introduction of the Mirror Girl.

The film has Lindbergh's crew working on the plane until the last moment before he flies, which necessitates screwing the compass to the ceiling of the plane with its readout pointing toward the instrument panel. A mirror brought from the factory is judged too heavy by the flyer, who asks the crowd waiting outside the hangar if anyone has a pocket mirror.

A young woman (Patricia Smith) steps forward to donate the mirror from her compact and gets a tour of Lindbergh's plane as a reward. It's nothing even remotely romantic; Stewart's Lindy treats the Mirror Girl like a gifted child when he shows her the cramped cockpit, but at least we see him interact with somebody in the film who isn't wearing a flight suit, greasy coveralls or a press pass in their hatband.

(Smith would spend most of her career on TV, with roles on Roots, The Bob Newhart Show and Star Trek: The Next Generation, though she played Jack Lemmon's wife in Save the Tiger (1973) and had her final role in Costa-Gavras' Mad City (1997). She died in 2011.)

Jimmy Stewart was a close friend of Wilder's and he campaigned to get the part, but despite that he wasn't the first choice to play Lindbergh. That would have been John Kerr, who had made a big impression as a suicidal artist in Vincente Minnelli's The Cobweb (1955) and alongside Deborah Kerr in Minnelli's Tea and Sympathy (1956). (Kerr would leave acting to become a lawyer, while still taking roles on television.)

But Kerr abhorred Lindbergh, who he considered a Nazi sympathizer, and turned the role down. Which brings us to the 65-ton Elefant Tank in the room: Charles Lindbergh's political and social beliefs.

Upon landing his plane at Le Bourget airport – and let's not pretend that's a spoiler – Lindbergh became the most famous man in America, perhaps the world, and his fame would linger for the rest of his life, though it would be mixed with tragedy with the kidnapping and death of his son Charles Jr. in 1932. But that fame turned into infamy in the late '30s when he became not just the figurehead of American isolationism but one of the most prominent apologists for Hitler's Germany.

As Sikov notes in his book, in 1938 when Wilder was funding the escape of European Jews from Nazi persecution, Lindbergh was being decorated with the Service Cross of the German Eagle by Hermann Goering, and becoming a mouthpiece for German propaganda claims about the size and strength of their air force. He and his wife even considered moving to Germany – to a house in Wannsee, of all places – and his only objection to Kristallnacht was to wonder that Germany "undoubtedly had a difficult Jewish problem, but why is it necessary to handle it so unreasonably?"

Neither Wilder nor Jack Warner, head of the studio that made the film, had any problem making a film about Lindbergh, though Sikov notes that Ernest Lehman, who co-wrote Sabrina with Wilder and Samuel Taylor, thought Wilder's interest in Lindbergh was typically "perverse".

Lindbergh was a consultant on the picture, which necessitated spending time with the director. They flew together on a commercial flight from L.A. to Washington where the flyer wanted to show the director his plane, on permanent display at the Smithsonian Institution. When the airliner hit some turbulence, according to Sikov:

"Wilder leaned over to his seat mate and said 'Mr. Lindbergh, would it not be embarrassing if we crashed and the headlines said, 'Lone Eagle and Jewish Friend in Plane Crash?' He just smiled. He knew exactly what I had in mind.'"

The more you study Lindbergh the more obvious it becomes that there was something undeniably off about the man – a hard pragmatism, deficit of empathy and emotional coldness that would find its expression in a belief in eugenics and its accessorizing crackpot social Darwinism. He counted among close friends other world class antisemites like Henry Ford, and never understood why his public statements in favour of Germany and its Nazi leadership before the war were considered scandalous.

Wilder found the flyer confounding and thought his inability to bring out real human qualities in the man to be a major reason why his film failed. "I couldn't get into his private life," he said. "He had become a Scandinavian Viking hero, without flesh and blood." He was a classic example of the Dunning-Kruger effect, where success in one, limited field confers a presumption of expertise in all others.

Which is why it was imperative that someone like James Stewart play Lindbergh, despite the 20-year gap between the young flyer and the middle-aged actor and air force veteran, which required Stewart to go on a diet and get his hair dyed blonde.

Stewart desperately wanted to play Lindbergh, a personal hero as an airman if not a public figure and went so far as to arrange a dinner with Leland Hayward and his wife, bringing along his own father and his new wife, with the elder Stewart pressing his son's case with the producer. Hayward got both Wilder and Jack Warner to agree, despite their objections, but it wouldn't be long before they'd regret their decision.

Billy Wilder is a director renowned for his comic touch, and he couldn't have made The Spirit of St. Louis without investing some charming eccentricity or lightheartedness into Charles Lindbergh despite the man. Stewart's strength as a comic actor began with his lankiness and boyish discomfort with adult formality; his Lindbergh makes stork-like jumps over wide puddles on the airfield, and fumbles with the ritual of lighting a cigar while trying to present his plan for flying the Atlantic to a room full of St. Louis businessmen.

It's hard to imagine how many actors could pull off another major invention of Wilder's – the dialogue Stewart's Lindbergh has with the fly who hitches a ride in his cockpit on the first leg of his journey across the eastern seaboard and the Maritimes to Newfoundland. The appeal at the heart of the story is a boy's own adventure, though by the '50s few people would have described the Lindbergh of the America First movement as boyish, and Wilder himself had never shown much interest in boys, or in adventures that strayed beyond hotels. To tell that story they needed someone like Stewart.

(The director applauded Stewart for his performance with the various flies needed to film these scenes. "Mr. Stewart did not object to talking to insects," Wilder said. "After all, he had to deal all of his life with agents and producers.")

But it's an inconvenient fact that the actor's boyish charm, which lingered improbably late into his career, masked a prima donna who could be incredibly difficult to work with. When filming began in Paris the film's star began complaining about shooting process shots in the cockpit of his plane, about the food, about being ignored and even his accommodations at the Ritz, and began threatening to leave.

Despite Stewart's long friendship with Hayward and Wilder, meetings over lunch and dinner meant to mollify him went very badly; the actor stormed out after Wilder lost his temper, and before the studio could buy Stewart and his wife tickets back to Beverly Hills, the actor had already booked an evening flight home.

Additional conflicts with Stewart's schedule, not to mention the usual difficulties shooting an aviation picture where weather was always an issue, led to Wilder blowing his schedule and Jack Warner's budget. Building three replicas of Lindbergh's plane, two of which were flyable, took up $1.7 million of the $7 million budget, and a shooting schedule of just over two months turned into one nearly twice as long. Before it was done Wilder himself had lost interest in the picture; Hayward and Warner replaced him with an uncredited John Sturges.

The length of the first edit of the picture demanded cutting far more critical than Jack Warner's typically boneheaded suggestions to make the comedy broader. A whole section of the film devoted to Lindbergh's friendship with fellow flyer Harlan "Bud" Gurney (played by Murray Hamilton – the mayor from Jaws) that Wilder thought essential to teasing out Lindbergh's personality was trimmed to a single flashback scene that tells us almost nothing.

Which isn't to say that there aren't some great moments and striking sequences in The Spirit of St. Louis. The cinematography by Robert Burks, J. Peverell Marley and the second units is often superb, and the scenes devoted to the building of Lindbergh's plane are more elegant than they have a right to be; Wilder asked his friend, industrial designer Charles Eames, to work on the picture as a photographer, and it's tempting to imagine that he had something to do with this sequence. Franz Waxman's score is excellent.

And Stewart's performance is as superb as it needs to be, considering how much of the film is just Lindbergh alone in the cockpit. Wilder's formula for the picture's drama was stark, described by Sikov in his book as "a man's effort to convince the money boys to finance his preposterous idea, his sweating blood to achieve it, his near-paralyzing fear of failure midnight, and the confusion and letdown of his enormous success."

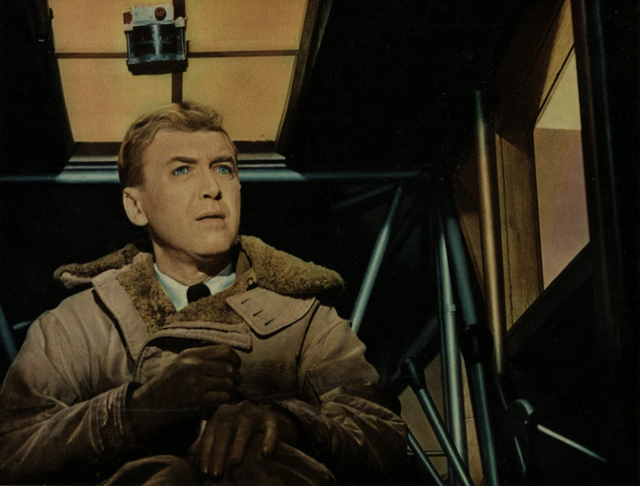

In simple terms, the biggest enemies Lindbergh fights are money and convention, but while crossing the Atlantic they become distance and physics. But since that's far too abstract the battle we watch Stewart fight while in the air is against sleep.

The actor had always had a talent for playing men at their breaking point; just look at his performances in films like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, It's a Wonderful Life, Rear Window, Vertigo and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, among so many others that define his onscreen persona.

Stewart plays this to great effect as Lindbergh, who hadn't slept for nearly two days before taking off from Roosevelt Field, has to stay awake and fly by dead reckoning for thirty-three hours in the chill over the North Atlantic. The flashbacks to his childhood and his early career as an aviator are part of the creeping delirium that overcomes the flyer with every hour in the air.

So it must have come as a shock when Stewart met Lindbergh during a set visit, and asked him at which point he was most tired during his flight. As Sikov recalls the encounter:

"'I never got tired,' Lindy replied. 'This was rather disconcerting,' Stewart later said, 'as I had based the whole performance on the fact that he did.'"

In the end the most poignant relationship in Wilder's film is between the man and his machine. Lindbergh's arrival at Le Bourget is filmed like a nightmare, which climaxes in the huge crowd gathered at the airfield breaking down the barriers and mobbing the aviator and his plane, pulling him out of the cockpit while souvenir hunters start looting the cockpit and tearing away pieces of the fuselage. (Lindbergh's original flight and engine logs were both lost when he landed.)

As they carry him away, Lindbergh keeps looking back desperately at the plane, reaching out and pleading vainly with the crowd to take him back: his obscurity ends with a vengeance, and they sweep him away to a future that would contain heartbreak and infamy. He gets just a single coda afterwards, in a hangar where The Spirit of St. Louis sits silhouetted in a dim light. The flyer gets one last farewell with the plane – a moment that has more poignancy and sorrow than anything the picture could have prepared us for.

A year and two days after their first flight, Lindbergh landed at Bolling Field (now Bolling AFB) and donated The Spirit of St. Louis to the Smithsonian, where it has been on display for over eight decades, currently hanging in the atrium of the National Air and Space Museum. He would visit the plane regularly until his death in 1974.

The producers knew they were in trouble when, as Sikov writes, they were "shocked to learn after a sneak preview of the film that hardly anybody under the age of forty knew who Lindbergh was. Their solution was to send teen heartthrob Tab Hunter out on a twelve-city tour."

The New Yorker even ran a cartoon with a boy and his father leaving a theatre showing The Spirit of St. Louis, the boy asking, "If everyone thought what he did was so marvellous, how come he never got famous?" In the end, making a film about a Nazi sympathizer turned out to be the least of their problems.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.