There's a cherished myth that the films made before the enforcement of Will Hays' Motion Picture Production Code in 1934 are a lost paradise of moviemaking: a frank, honest, adult cinematic universe that we were only able to return to with the abandonment of the Code in the '60s and the emergence of a school of movie radicals – the "raging bulls" of Peter Biskind's famous book – who blew away the fusty moral cobwebs from Hollywood.

Part of this is a reaction to Joseph Breen, the man who Hays put in charge, and who ruled over the production offices and editing rooms of Hollywood until his retirement in 1954. Breen was, to be sure, an unpleasant character – a textbook establishment antisemite and proudly ignorant scold. Knowing that he had final say over your work must have been galling.

But it has to be remembered that Joseph Breen didn't make the movies: Howard Hawks and Ernst Lubitsch and George Cukor and James Whale and Frank Capra and Preston Sturges and Billy Wilder and Dorothy Arzner and Mitchell Leisen and Fritz Lang and Elia Kazan and many others did. And that by the time Breen retired, the code was being undermined by both the studios and independent producers. It would limp on for another decade but its end in 1968 was little more than burying the corpse that had been mouldering in plain sight.

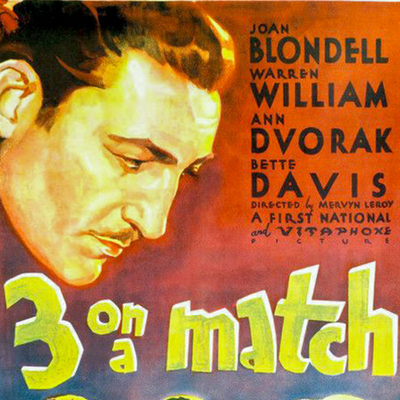

But let's examine this myth of the pre-Code picture by looking at one that's considered a classic – Mervyn LeRoy's Three on a Match (1932), made by First National Pictures and distributed by its parent company, Warner Bros. The film begins with a news and headline montage that tells us it's 1919 by summing up three key events: the signing of legislation enacting Prohibition and women's right to vote in the US (the two of them inextricably linked) and the lifting of hemlines on skirts.

The camera takes us to a public school playground in New York City, where we meet a handful of grade school children. The boys are a generic lot except for Willie Goldberg, a walking collection of Jewish stereotypes right down to pushy parents barely a decade or so out of Ellis Island and the shtetl.

But we're meant to pay attention to three girls, first among them Mary, played by child star Virginia Davis, who started her career playing Alice for Walt Disney in his early short films. Mary is a tearaway who we see hanging upside down from the swings showing her black bloomers to the obvious interest of Willie and the other boys.

Her exhibitionism garners the disapproval of Vivian – and no small amount of jealousy, as she makes a point of telling one of the boys that her bloomers are pink, should he be at all interested. Which he isn't, as he joins another boy to cut class and smoke cigarettes with Mary in a toolshed.

(Vivian is played by Anne Shirley, who would have significant parts in pictures like Stella Dallas, The Devil and Daniel Webster and Murder, My Sweet, even playing her fictional namesake in two films based on Lucy Maud Montgomery's books before retiring from Hollywood at 26.)

The third girl is Ruth, played by Betty Carse who, despite being eerily perfect in a part that will be played as an adult by no less than Bette Davis, has only one credit with this picture. Ruth is the third wheel in the group, and despite having the highest marks in her class – in the history of graduating classes at the school – is headed for secretarial school after graduating, a working class girl with ample skills but no means.

(Ruth's thankless function as the surplus pole of the trio in the picture is not just an example of the picture's broad, even rudimentary script, but a terrible waste of Bette Davis.)

Vivian, the valedictorian, is destined for girls' boarding school and the necessary refinement as a rich man's wife in society, while her friends joke that Mary is destined for reform school – exactly where we see her next, played as an adult by Joan Blondell.

The movie might be among the earliest – though probably not the first – to depict American public school as a melting pot of not just ethnicities but classes. It's a cherished cornerstone of Hollywood's conception of the democratic society that continued through Rebel Without a Cause to The Breakfast Club and Heathers to the present day. I am not sure if it is still, or ever was, strictly true.

When we meet Mary again it's 1930 and she's in a beauty salon getting her hair permanent waved by one of those tentacled, Lovecraftian devices that look potentially lethal. A neighbour in an adjacent booth overhears her talking and tells the attendant to introduce her as a schoolmate. That neighbour turns out to be Vivian (Ann Dvorak), now a mother and married to Robert (Warren William), a wealthy lawyer.

The three friends reunite over lunch where we see them light their cigarettes with that fateful, titular match. Mary is a showgirl waiting for her big break, Ruth is working in an office and Vivian is frankly bored and restless, unhappy with her life despite getting everything her friends can only dream of having, including the chauffeur and limousine waiting for her at the kerb outside the restaurant.

Back at home with her husband, Vivian is pretending to be asleep when her husband comes to bed. They talk honestly, and he agrees that she should go to Europe with Robert Jr. for a while (the equivalent of therapy, one supposes, for their class at that time.) But after Robert says goodbye to his family in their suite on the ocean liner she runs into Mary and a group of her friends who are seeing off another passenger at a party in their cabin.

One of the friends is Michael (Lyle Talbot); he flirts with Vivian, she flirts back, and just before the ship sails she takes her son and runs away with the man who closed his play for her with the taunt that "You don't know what life is."

In his book Complicated Women: Sex and Power in Pre-Code Hollywood, Mick LaSalle makes a forthright argument in his introduction that pre-Code films offered the best, most positive and progressive vision of female characters in film, and not the "women's pictures" of the Forties "with ladies with big shoulder pads and bad hairdos watching their boyfriends light two cigarettes at the same time."

"The best era for women's pictures was the pre-Code era, the five years between the point that talkies became widely accepted in 1929 through July 1934, when the dread and draconian Production Code became the law of Hollywoodland. Before the Code, women on screen took lovers, had babies out of wedlock, got rid of cheating husbands, enjoyed their sexuality, held down professional positions without apologizing for their self-sufficiency, and in general acted the way many of us think women acted only after 1968."

"They had fun," LaSalle writes. "That's why the Code came in. Yes, to a large degree, the Code came in to prevent women from having fun."

Which prompts one to look for just what kind of fun women like Vivian are having in Three on a Match. Certainly there must be something crucial missing from her life to make her do something as drastic as abandon her husband and run away with their child to live with the first man who dared her to throw her life away if she wasn't enjoying it.

LaSalle says that Vivian "doesn't know" what is making her "edgy, neurotic, restless, miserable. 'I just seem feed up with everything,' she tells her concerned husband... 'Somehow the things that make other people happy leave me cold,' she says at the start of the picture. 'I guess something must have been left out of my makeup.' Maybe. Or maybe she has a little extra something. Maybe she craves something that her world doesn't offer her. Finding no fulfillment in comfortable domesticity, and lacking a legitimate creative channel, she is devoured by her own energy."

Ann Dvorak is given what is ultimately the unenviable task of embodying all this restless, self-destructive energy as Vivian goes from adulterous wife on the lam to cocaine addict neglecting her child, telling him when he whines about being hungry to eat the party leftovers on a tray of hors d'oeuvres. Even this is too much for Michael, the heel who's spending her money, and he tells her to order some food for herself and the boy.

"Slim and dark-haired, Dvorak was like a tough kid sister, the type who knows the score without anybody having to explain it to her," LaSalle writes about the actress. She was only twenty when she played Vivian, just after a sensational turn as Paul Muni's sister in Howard Hawks' Scarface, emerging from a career playing bit parts.

Dvorak, according to LaSalle, played Vivian "like an addict, every nerve raw." There's no denying that her Vivian radiates a dark energy. She reminds me of Jeanne Eagels in another pre-Code film, the 1929 version of Somerset Maugham's The Letter, though Dvorak is (gratefully) pitched a level of magnitude lower than Eagels. My friend Kathy Shaidle marveled at Eagels' performance in this space, describing it as a "raw-nerve-from-outer-space approach (that) seems, at once, old fashioned and ultra-modern. (Is she unsure the camera is rolling, or all too aware of its presence?)"

Dvorak's Vivian definitely stands out among the other performances in Three on a Match, but I'm not sure if it's her intensity, bad direction from LeRoy, or simply an inability to perform for the camera that looks like so many other awkward performances from the pre-Code early talkies era.

I can't help but compare her with Joan Blondell, whose Mary intervenes to reunite Vivian's son with his father and ends up marrying Robert Sr. when his divorce from Vivian comes through. She goes from reform school to chauffeured limo in what seems like minutes in the breakneck pace of LeRoy's very economical (just 63 minutes!) story. Poor Ruth only gets a gig as Junior's nanny, but at least Davis looks cute in a swimsuit during the beach scene.

"There is no such thing as a movie so good that it could not be made a little better by Joan Blondell," writes LaSalle. "Self-possessed, unimpressed, completely natural, always sane, without attitude or pretense, Blondell was the same at twenty-two as she would be at seventy, in Grease (1978): the greatest of the screen's great broads. No one was better at playing someone both fun-loving yet grounded, ready for a good time, yet substantial, too."

There are so many performances in the film that would look just as natural in a film five, ten or even twenty years on, from Blondell and Davis to Edward Arnold as Ace, the gangster Michael is into for two grand in gambling debts, and Humphrey Bogart as his cold-blooded henchman Harve. They have the effect of isolating Dvorak's Vivian, even depriving her of our sympathy during her tumble into dissipation and addiction and making Robert Sr.'s pivot to Blondell's Mary entirely understandable.

Dvorak definitely sells Vivian's squalid fall into addiction, and like so many pre-Code pictures you can't help but be taken aback by her dry, flyaway hair, the dark circles under her eyes and compulsive nose-rubbing. But there's an artlessness to the way pre-Code movies go out of their way to shock us and flaunt the sordid and titillating that – like Dvorak's performance – don't make them seem contemporary as much as an artifact from the other side of some essential shift in movies.

And while the dawn of the Production Code was part of that shift, I don't think it was the only factor in play, or even the most important. There was the demoralizing effects of the Depression followed by the life-or-death struggle of a second World War. But there was also the increasing sophistication of moviemaking once it had solved how to make the camera move and even dance again after being encumbered with the weight of sound recording technology.

There are plenty of defenders of the Code – or at least those who (like me) think that it forced limitations on filmmakers that the truly creative rose to challenge, work around and subvert. (It also forced an ad hoc barrier between Hollywood and its sordid cousin, the porn industry, that held for decades but is merely notional today.)

But then there's the undeniable fact that, at least in a film like Three on a Match, Vivian's desperate lunge for a life filled with fun doesn't make her any happier. It definitely makes her palpably unlikeable and while her child gets filthier, Vivian's ladylike manners disappear into sullen glares when she isn't passed out in her clothes next to ashtrays and bottles.

Many of us have certainly known people as self-sabotaging and damaged as Dvorak's Vivian, and have been forced to stand by helplessly while they either suffer the consequences of bad decisions or find a way to rally and preserve what's left of their lives – perhaps even find something like redemption.

But given the brevity and relentless pace of LeRoy's picture, Vivian's journey is turbocharged to its tragic destiny. Defenders of pre-Code pictures like LaSalle celebrate how "bad girls" aren't inevitably punished for their transgressions as they would be in Breen's Hollywood. But Vivian does not survive to the final credit roll of Three on a Match, though her awful death, brutally shot, is a kind of redemption. Breen would never have let an audience witness the details of Vivian's downfall, but he would have definitely approved of her ending.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.