Even as the bad reviews poured in, I knew I was still going to see Ridley Scott's Napoleon – and in the theatres, no less – if only for a chance to see a new movie where there was little chance of backstory, character and major plot points being instigated by someone staring at the screen of their phone.

And make no mistake, the reviews have been brutal. "So, is Napoleon dynamite?" asked Anthony Lane in the New Yorker. "Not if you're a historian." "An incoherent epic," writes David Fear in Rolling Stone, "one whose shortcomings aren't trying to make up for stature or status but arise from an uncertainty of perspective."

"'Middling' and 'epic' are not words you want to see together, but there you are," writes Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune. Writing about star Joaquin Phoenix in the New York Post, Johnny Oleksinski says that he "gives us his same creepy, whack-job performance from Joker, only now Arthur Fleck is accompanied by a pointy hat, massive scenery, impressive battles and a supremely skilled co-star in Vanessa Kirby."

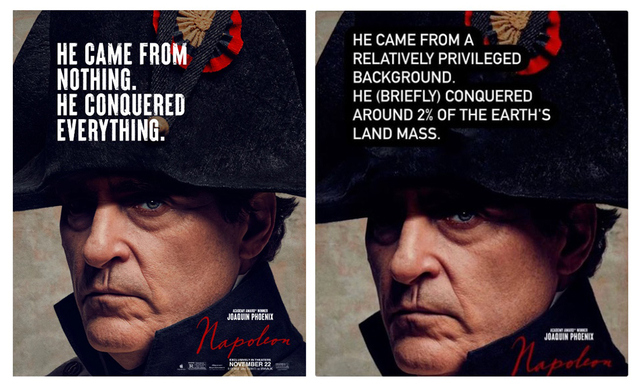

But nothing beat the beatdown Scott's film got from French critics: "Very sure of its inanity"; "An Austerlitz of cinema? More like Waterloo"; "A bit vulgar, a bit rude, with a voice from elsewhere that doesn't fit at all."

Ultimately, no torrent of pans could deter me from buying my matinee ticket in search of answers for the two questions I've been asking since I learned about Ridley Scott's big-budget biopic. Namely – why Napoleon? And why now?

The film begins not with the titular hero but with the Terror and the tumbrel, and the crowd gathered at what's now called the Place de la Concorde for the guillotining of Marie Antoinette. Scott puts Phoenix's Napoleon in the crowd, alone and impassive, perhaps even disgusted, amidst the mob baying for the queen's blood.

Never mind that Napoleon wasn't in Paris at the time but at the Siege of Toulon, the scene of his first major victory and the start of his incredible ascension from an obscure artillery captain of provincial origins. Which is fair, if Scott wants the audience to understand just how improbable Napoleon's career was, if not for an accident of history that put this nobody in the right place at the right time.

But things move quickly when a country is in chaos, and with the fall of the Jacobins Napoleon gets a chance to prove himself at Toulon, where he leads a nighttime assault on the royalists and their British allies. He gets his horse shot out from underneath him but Scott, not content to just have the poor steed collapse underneath Napoleon, has the beast take a cannon ball full in the chest. Later, after his victory and his promotion to brigadier general, Napoleon pulls the iron ball out from the carcass and tosses it to his brother, Lucien (Matthew Needham), telling him to send it to their mother.

Flush with success, Napoleon returns to Paris, which is in party mode after the fall of the Jacobins and the release of their condemned prisoners from the jails. Among them is Josephine (Vanessa Kirby), whose husband, an aristocratic army officer, was a victim of the guillotine. He lacks manners or charm but is blessed with unshakeable confidence and the aura of a man on his way up in a society where all the old rules have been swept away, and he makes himself indispensable to the ruling Directory by ruthlessly putting down a royalist rebellion in the capital with the famous "whiff of grapeshot."

Their relationship is central to Scott's telling of Napoleon's story, since the meteoric rise of a man who redrew the map of Europe and put history in his shadow for over two centuries afterward is clearly not sufficiently compelling or "relatable". At first she's a siren, a woman of beauty and experience who has the young man (six years her junior) in abject sexual thrall from the moment she spreads her legs and tells him to look down to see "a surprise", and that "once you see it you will always want it."

The scene is a scriptwriter's vivid invention, but there's plenty of evidence that Napoleon's relationship to his first wife was just this obsessive, thanks to the massive volume of correspondence that Napoleon left behind, in addition to essays, novels and short stories. Today, when all behaviour is pathologized, we might diagnose him to be suffering from hypergraphia or graphomania, but he's one of a handful of historical figures of whom we can't say that we can only guess what he was thinking.

Answering the critics who listed all the historical inaccuracies in the picture, Scott was remarkably truculent, telling the BBC that his film was "not a history lesson by any means," and responding to a TikTok post by historian Dan Snow listing the fabrications by saying "Get a life." In an interview with Snow on YouTube, he dismissed the criticism by asking "How do you know? Were you there?"

But many people were there, and given Napoleon's incredible fame (and infamy), it would appear that most of them recorded their memories and experiences. And though much of what was written by and about Napoleon was mythmaking, score-settling and propaganda, the historical record is deep, and Scott's inventions – some simply old myths repeated, some newly minted – are bound to be noted.

Now married to Josephine, the film blithely skips over the conquest of Italy and follows Napoleon to Egypt, where he went to threaten British trade routes to their empire in India. Scott sets the Battle of the Pyramids directly in front of the Pyramids at Giza instead of miles away in what's now the Cairo suburb of Imbaba.

His army faces the Pyramids and the massive Mamluk army; Napoleon orders a single cannon volley that strikes the top of one of the Pyramids, which sends the belligerent Mamluk leader we presume is Murad Bey tumbling in shock from his horse. Napoleon turns on his heel in disgust and sails back to France where Josephine is having an affair with a young hussar.

Napoleon did go to Egypt, where he did defeat the Mamluk army, and Josephine did have an affair with a hussar, Hippolyte Charles. Everything else in the scene is pure invention.

In his wildly entertaining book The Hollywood History of the World, George MacDonald Fraser (author of the Flashman novels) writes that "there is a popular belief that where history is concerned, Hollywood always gets it wrong – and sometimes it does." And yet, he continues:

"What is overlooked is the astonishing amount of history Hollywood has got right, and the immense unacknowledged debt which we owe to the commercial cinema as an illuminator of the story of mankind. This although films have sometimes blundered and distorted and falsified, have botched great themes and belittled great men and women, have trivialised and caricatured and cheapened, have piled anachronism on solecism on downright lie – still, at their best, they have given a picture of the ages more vivid and memorable than anything in Tacitus or Gibbon or Macaulay, and to an infinitely wider audience."

And with these words in mind – and while silently pleading with the screen at every outrageous yet cinematic fabrication, to the exasperation of my youngest child, who doubtless regretted attending the matinee with me – I pressed on with Ridley Scott's Napoleon.

The penultimate step on Napoleon's rise to absolute power was Brumaire, the 1799 coup against the Directory. To the average Frenchman it would only have been the latest in a series of coups and purges since the fall of the Bourbons, which had names like Thermidor, Vendémiaire, Fructidor and Prairial. Corruption and hyperinflation threatened the Revolution, and Napoleon allowed himself – one might say positioned himself – to be at the head of the coup, representing the military that was essential to bringing the whole thing off.

Scott's film skips Napoleon's address to the Elders, the senior house of the government, and has him barge in on the meeting of the Five Hundred, the junior house where his brother Lucien is trying to press the business of the coup against opposition that flares into violence when Napoleon enters the chamber. According to Napoleon the Great, Andrew Roberts' biography, the deputies "had started to push, shake, boo, jostle and slap Napoleon, some grabbing him by his high brocaded collar."

There's something undeniably comic about the scene – probably the last moment outside the battlefield where Napoleon would be in danger – and Scott plays it big, with Phoenix's Napoleon fleeing from the chamber, tumbling down a set of stairs before escaping the building, then hammering at the arms that are reaching out for him while his allies hold the doors against the angry mob. He then calls upon his soldiers to march back into the building and pacify the deputies at bayonet point.

It isn't long before Napoleon the man becomes Napoleon the Emperor, crowning himself at the ceremony in Notre-Dame. Scott only has to bring him to the apex of his reign, and then onward to the downfall. The high point is Austerlitz.

Napoleon fought against seven coalitions of enemy nations during his reign, with Austerlitz the battle that defeated the third. It's neither the largest (that would be the Battle of Leipzig, against the sixth coalition) or the most iconic (Waterloo, fought against the seventh), but it was the one that defined his reputation as the "God of War" and made the Emperor seem, at least for the moment, look unbeatable.

The battle was the pinnacle of his revolution in battlefield tactics, which involved powerful and mobile self-contained corps, feints and strategic retreats and sudden flanking and enveloping moves. Scott puts much of his considerable cinematic skill into the battle, over which Phoenix's Napoleon presides like a bored deity, observing the Austrian and Russian troops falling into his trap through hooded eyes, signalling the artillery coups de grace with a slight wave of his hand.

His enemies are forced to retreat in a mass over what they discover to be a frozen lake, which Napoleon's cannons shatter, in a sequence that evokes the defeat of the Templars on Lake Peipus in Eisenstein's Alexander Nevsky. A cavalryman carrying his battle standard tries to escape, galloping between icy explosions before plunging into the black water. It's a phenomenal scene.

The terrible denouement to Austerlitz has been part of its myth for two centuries, and while Napoleon found only the bodies of horses and not soldiers when he had the lakes drained after the battle, and recent excavations did turn up "only a dozen corpses and a couple of guns" according to Roberts, this image of war's horror at the moment of victory would be irresistible to any director with the budget to bring it to the screen. It's truly epic, and nobody sits down to a movie about Napoleon without expecting the epic.

Between the triumph of Austerlitz and the defeat at Moscow lies a stretch of domestic melodrama when the new Emperor realizes that, like the head of any dynasty, he needs an heir and Josephine cannot provide one for him. It's no coincidence in the logic of Scott's film that things begin to go wrong for Napoleon when he divorces Josephine and exiles her to the Château de Malmaison.

It's hard at times to know if Scott and Phoenix are playing Napoleon for laughs. Except at Austerlitz, he groans and hyperventilates before heading into battle, and then there's that pratfall at Brumaire. Kirby's Josephine is overcome by giggles in response to his clumsy physical attentions, and at least twice his inflamed passions with her culminate in what can only be described as a frenzied burst of rumpy-pumpy.

Two of the most quoted lines in reviews of the picture so far are the increasingly portly Napoleon arguing at the dinner table with his wife and musing that "Destiny has brought me this lamb chop," and exploding at the British ambassador that "You think you are so great because you have boats!"

Napoleon's ardour for Josephine – considered a great beauty despite having small, blackened teeth, a legacy of chewing sugar cane as a child on her family planation in Martinique – is well-documented thanks to his startlingly frank letters, and this picture of him in sexual thrall to her was established during his reign, when the British began a propaganda campaign to smear him using intercepted correspondence. This is the same concerted attack on his public image that painted him as short (he was on the low end of average height for the time), afflicted with an oversized head and tiny hands, and a cuckold given to frequent childish tantrums.

Writing about the couple after her affair with Hippolyte Charles, Andrew Roberts says that "they slipped into comfortable domestic happiness, until dynastic considerations emerged a full decade later. She seems now genuinely to have fallen in love with him, although she always called him 'Bonaparte'. The story of Napoleon and Josephine is thus certainly not the romantic Romeo-and-Juliet love story of legend, but something subtler, more interesting and, in its way, no less admirable."

But in Napoleon it's played out as tortured, a power play that, at least in its early phase, resembles the abject relationship between an incel and his beloved online thot. It's significant that he only discovers her death from pneumonia after his return from his first exile and on his way to the battle at Waterloo. Her exile precipitates his fall, and her death makes his final defeat possible.

(In real life Napoleon had learned of Josephine's death while still in exile on Elba. The truth – that she fell ill after a walk in the rain at Malmaison with Tsar Alexander I – is actually far more interesting, and Scott's decision to omit it is disappointing.)

Napoleon's long finale is the part of the story most people are familiar with if they're familiar with him at all, and the film tries to provide suitably vivid imagery. Scott chooses to show him riding into battle not once but twice, at Borodino and at Waterloo. Trained as an artillery officer, he would never have ridden with his cavalry, and there's no record of him fighting on the front lines after his first Italian campaign. But there's nothing that thrills the camera more than a cavalry charge in tasteful slow motion.

Nemesis arrives in the form of the Duke of Wellington, who Rupert Everett unfortunately plays as a classic English toff, disdaining the resurgent Napoleon as "vermin" who needs to be stamped out. And Scott's Waterloo is a painful oversimplification of the actual battle, dismal to watch especially if you've sat through all of Sergei Bondarchuk's Waterloo (1970).

For Bondarchuk, Rod Steiger – another American – played a Napoleon that George MacDonald Fraser considers every bit as good as Charles Boyer's in Marie Walewska (1937); he calls him "just Napoleonic," and judges that Christopher Plummer's Wellington "has a kinder face" than the original. Bondarchuk's painstaking depiction of the battle, filmed with thousands of uniformed Soviet army extras, will spoil you for almost any war film showing massed ranks on open fields, and ends without the two generals ever meeting each other.

Scott can't restrain himself from imagining that meeting, and has Everett's Wellington sit down across from Napoleon as he dines in the captain's quarters on the HMS Bellerophon, docked in Portsmouth before taking the defeated emperor to his last exile at St. Helena. Before they talk, Wellington is appalled to discover the midshipmen on the Bellerophon raptly listening while Napoleon holds court, and is told that the boys are fascinated by him.

The meeting never happened, but Roberts recalls in his biography of Napoleon that George Home, one of those midshipmen, wrote in his memoirs how "He showed us what one little human creature like ourselves could accomplish in a span so short."

The teaching of history was once assailed by critics who decried the "great man" theory of history, prevalent for so long, in which someone like Napoleon dominated the story as much as Caesar and Alexander. (A position that Napoleon himself would have considered worth occupying, despite his ending.) But a film like Napoleon seems like a subversion of the idea of the "great man", despite not making much room for anyone else who occupied the stage alongside the Emperor – not Wellington or Nelson, not Talleyrand, not Blücher, not Alexander, not even Ney (who had an ending that was truly tragic.)

But Phoenix and Scott's Napoleon is so comic, even pathetic, that French critics have complained that Scott just delivered another piece of typically British Napoleonic propaganda. Even his end when it comes at St. Helena – the famous man in his famous hat, seen from behind, simply slumping over and out of the frame – begs to be scored with the sad moan of a trombone.

It seems like a Napoleon made to fit a time when our political leaders seem not just flawed but damaged – victims of their pursuit of power at all costs, at a time when the bench is not deep and no one blessed with sanity, dignity or intelligence would endure the endless compromises or want to bask in the awful glare of political limelight.

At the remove of two centuries, it's probably time to reassess just who and what Napoleon was and meant; in his book, Roberts puts forward a significant "what if?":

"Who is to say that a Europe dominated in the nineteenth century by an enlightened France would have been worse than the one that eventually transpired, in which Prussia dominate Germany and then forced itself onto the continent in ways far less benign than Napoleon?"

It's a big question, but it wasn't one that was going to be answered by the film I saw, and I doubt if it will be answered by Scott's director's cut of Napoleon, four hours long when it's due to stream on Apple+. And that as disappointing as that is, I'll watch it nonetheless, still not really sure if I've gotten answers as to either of my questions.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.