Irony is to history what a pun is to humour – low-quality stuff, but sometimes it makes you stop and wonder. When Carole Lombard needed to get back from a war bond drive in Indianapolis to Hollywood and her husband Clark Gable (who she suspected of an affair with Lana Turner), she wanted to fly against the wishes of her mother Bessie and MGM press agent Otto Winkler. They settled it with a coin toss, described by Warren G. Harris in his book Gable & Lombard: A Biography:

"Winkler took an Indian-head nickel from his pocket and flipped it in the air. Heads, they would go by train, tails by plane. Lombard clapped her hands and squealed delightedly when the nickel landed tails up."

The three of them boarded the TWA milk run that would make several stops on its way to the west coast, crashing just after takeoff on its last leg out of Las Vegas and killing everyone on board. A decade earlier, in the only film Gable and Lombard made together, their characters decided to get married based on a coin toss.

But they hadn't hit it off then, not even close. Harris summed up their relationship during filming as "a case of mutual dislike at first sight, he objecting to her boisterous behaviour and profane vocabulary, she thinking he was too stuffy and reserved."

They wouldn't meet again for another four years, at a ball Lombard co-hosted with David O. Selznick, and the old revulsion was mixed with an attraction that was hard to ignore. It led to a weeks-long courtship dance that was straight out of a screwball comedy – if you could make a screwball with a hard "R" rating in 1936.

At one point, during a party thrown for the wife of a friend of Gable's who'd just had a nervous breakdown, Lombard arrived in an ambulance with the sirens running, and had herself carried into the living room on a litter under a white sheet by uniformed attendants. When Gable stormed away from what he thought was a very tasteless joke, she cursed after him that "I always knew Gable was a stuffed shit – I mean shirt."

When he took her aside to dress her down for the gag, she shot back that his "battle-axe" wife had ruined his sense of humour and sent Gable away in a sulk. Walking past Wallace Berry after their confrontation, Lombard said "That cocksucker's worse than a stuffed shirt. He's an insulting heel."

After a three-year affair that was an open secret in Hollywood, the couple eloped and were married in Kingman, Arizona on March 29, 1939. They would have barely three years together.

When they made No Man of Her Own for Paramount Pictures in 1932, Lombard was married to William Powell, sixteen years her senior, with whom she had co-starred in two pictures in 1931: Man of the World and Ladies' Man. Their marriage lasted barely more than two years.

Gable was on his second marriage in 1932. His first was to a woman seventeen years older than him, his acting coach and manager Josephine Dillon, and his second was to socialite Maria Franklin Prentiss Lucas Langham, born the same year as Gable's first wife. Neither marriage had stopped Gable from being notorious for affairs with his co-stars or any other woman that caught his fancy.

Gable had become a heartthrob with an image that sold him as a rough piece of work in a good set of clothes. His star status had been buffed up as co-star to Joan Crawford in several pictures (including Dance, Fools, Dance, Laughing Sinners and Possessed) and he came to expect that he'd catch the fancy of any woman he chose – which included Crawford. By and large, it was good to be Clark Gable.

In the picture, directed by Wesley Ruggles and based on a novel by none other than future director and horror pioneer Val Lewton, Gable's Jerry "Babe" Stewart is a charming heel – a character type he had already mastered, and would explore on and off for the rest of his career. Babe is a card shark running a crooked game with his associates Charlie (Grant Mitchell) and Vargas (Paul Ellis), fleecing rich businessmen groomed as marks by Babe's girlfriend Kay (Dorothy Mackaill).

After one late night of high-stakes poker, played in white tie at Kay's apartment, Babe is in a bad mood despite taking a bank president named Morton for thousands, and decides now's as good a time as any to break up with Kay.

"You know I'm a hit and run guy," Babe says while she pleads with him. "Did I ever tell you I love you?"

Kay gets desperate, threatening to turn him over to the D.A., and a police detective who's been tailing him drops by on the bickering couple to warn Babe that he's out to put him behind bars. Babe decides to leave town while things are hot, flipping a coin to decide whether he'll take a plane or a train (the coin says train) and picking his destination by closing his eyes and poking his pen at a railway timetable.

He ends up on a New York Central train to Glendale, which is far enough from New York City to require a sleeper car, though all we need to know is that it's the kind of small town where old men play checkers in the lobby of the only hotel, and that a bicycle bell is the loudest sound you'll hear on Main Street.

Waiting for him there is Connie Randall (Lombard), the local librarian, bursting with restlessness and impatience. We meet her at home getting ready for work, battling with her overprotective mother over whether she can spend the weekend in a cabin at the local beauty spot with a group of friends – an annual outing that's presumed to be as immoral as things get in Glendale, though Connie says its reputation is wholly oversold, though she wishes it wasn't.

She's the kind of woman who, as she tells her mother, goes off into the woods to scream, and Lombard sells her frustration and simmering rage superbly. There's a convention in screwball comedy that the heroine can be described by a low-class character as a "screwy dame," but Lombard – still a few years from becoming one of screwball's great sirens – sells us explicitly on just why that would be the case.

Connie catches the eye of bored Babe when, still radiating nervous anxiety from the argument with her mother, she marches across Main Street to the newsstand where she throws dice with the proprietor to see whether she'll pay for a pack of gum. No Man of Her Own is a decidedly pre-code but proto-screwball picture, though the most screwball thing about it (besides the presence of Lombard) is the intimation that there's a world of anarchic, licentious, unreasonable behaviour hiding just beneath the veneer of civilization – even in a place like Glendale.

Babe follows her to the library and puts a hard press on her. She's not immune to his potential as her means of escape from Glendale – just a few minutes earlier she'd threatened her mother that "if I disappear someday, you'll know that I ran off with the first traveling salesman who didn't have gold teeth!" But she knows she has to at least play hard to get with a man like Babe, despite the urging of her matronly co-worker that she needs to strike while his particular iron is hot.

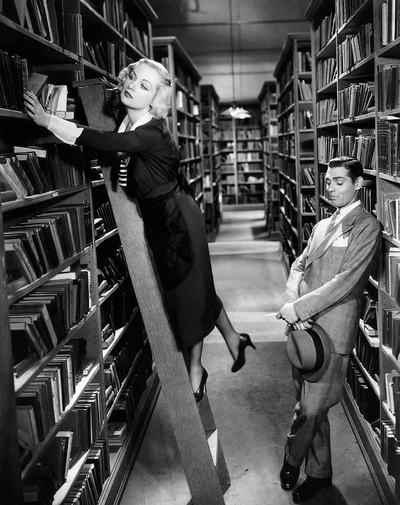

Babe gets a library card and follows her into the stacks under the pretense of looking for something to read, indicating some volumes on a high shelf as a ruse to get a long glimpse of her legs. Intent on taking her out after the library closes, he conspicuously hangs out for the rest of the day while tightening the emotional screws on the already anxious Connie.

No Man of Her Own is, as I said, a pre-code picture, full of titillating scenes like ones where the camera leers at Mackaill and Lombard's legs, or Lombard strips down to her silk undergarments in her cabin or showers with only a steamed panel of glass between her and the camera. But that means that it's also a movie from the first half-decade of sound pictures, where the newly unwieldy camera locks itself off stiffly for two-handed dialogue scenes.

But director Ruggles (I'm No Angel, True Confession, Too Many Husbands) was too talented to let his camera sag into static framing, and it breaks free in the scene after the library finally closes. Gable's Babe is nowhere to be found, and Connie's colleague asks her to go into the stacks and turn off the lights between the shelves.

Ruggles' camera positions itself overhead, and we watch Lombard walk warily through the shelves, extinguishing the light as she goes, her eyes darting around as she looks for Gable. She's like Theseus in the Minoan labyrinth, hunting for and being hunted by Gable's Minotaur. He surprises Connie and presses a long kiss on her, but she fends him off again with a promise and a warning: "See you in church!"

Babe rises to her challenge and shows up at Sunday services, walking up to her family in their pew and wordlessly making her little brother squeeze aside so he can sit next to Connie. This leads to an invitation to the Randall home for ice cream and cake and stiff small talk with Connie's mother, who bets that he "doesn't hear any better preaching in New York than he heard today."

"I'm afraid you're right," Babe replies coolly.

Just what made Gable such a heartthrob in the early '30s is on ample display here; his Babe is relentless but measured, a predator unable to shift his attention until he's taken his quarry. (Though thanks to Connie's frank talk with her matronly but eager colleague in the library we know that the prey is, more often than he thinks, toying with him.)

He pursues her to her cabin at the beauty spot and issues an ultimatum: he has to get back to the city so whatever happens next has to happen fast. Both gamblers, she ups the ante with marriage, they settle with that coin toss, and after a shot of a ring being slipped onto a finger they're in their shared sleeper on the New York Central and a post-coital shot of a delirious Connie the following morning while the scenery rolls past the window. There's still a lot of movie to come, but as James Harvey says in his indispensable Romantic Comedy in Hollywood from Lubitsch to Sturges:

"'I'll gamble on anything,' he says. On her virtue? Tails, he wins and she loses it; heads they get married – and go to New York. She wins. (But the movie loses; she spends the rest of it as his wife reforming him.)"

It's hard to believe now that there was no offscreen chemistry between Gable and Lombard while they made No Man of Her Own, despite his reputation and what we see onscreen. But the record is clear, and there's no reason to doubt it even nine decades later. In the picture Babe gives Connie the nickname "Ma", so Lombard mockingly called Gable "Pa" offscreen.

She thought he had a fat head, he thought she was crude and overbearing. When filming ended he presented her with a parting gift: a pair of oversized ballet slippers with a card that read "To a true primadonna." She gave him a huge ham with his face on it. They parted ways, and because they were signed to different studios for much of the following decade, never teamed up onscreen again.

No Man of Her Own wasn't a total flop – it did worse than Three On a Match but better than 20,000 Years in Sing Sing – but it didn't set the world on fire, and director Ruggles was particularly disappointed that Lombard's performance hadn't been praised more. When he was interviewed in 1974, as quoted by Harvey in his book, he said that:

"I was damned impressed, though nobody else seemed to be. I loved the first part of the picture – it had a lot of realistic comedy crammed in, and this was what we had decided to work for. Carole and Clark both knew exactly what they were doing...Yet I thought Carole was the revelation...Look at the picture today. It's dated, but her work hasn't. She's very fresh. She's playing straight but using comedy techniques too. Those idiots who'd taken over the studio – they couldn't even see that. Well the critics didn't see it either. She was wonderful, but it was just passed by..."

Two years later Gable would be loaned out again by MGM, this time to Columbia, and he resented it so much that he showed up drunk for the first day of shooting on Frank Capra's It Happened One Night. Once again he didn't get along with his co-star, Claudette Colbert, but the onscreen chemistry was undeniable and the picture was a massive hit, sweeping that year's Oscars and helping galvanize screwball comedy into a palpable subgenre.

That same year Lombard was loaned to Columbia to make another picture that would define screwball comedy. Twentieth Century was directed by Howard Hawks and while it didn't do as well as It Happened One Night – it was a major bomb at the time – it's considered a classic today, and Lombard got the reviews Ruggles thought she'd deserved two years earlier, and her career as a star comedienne as finally launched.

It's tempting to imagine what would have happened if Lombard and Gable had teamed up together again. She was considered for Colbert's role in It Happened One Night; Miriam Hopkins, Myrna Loy, Loretta Young and Margaret Sullavan all turned it down, and Lombard was unable due to shooting conflicts on Ruggles' Bolero with George Raft. Bette Davis also wanted the role – there's an alternate history worth imagining – but also had to turn it down because Jack Warner refused to lend her out.

Lombard and William Powell divorced but remained friends, and made another screwball classic together, My Man Godfrey (1936). She partnered with Fred McMurray for four great screwballs, and did a reprise of the frustrated small-town girl as Hazel Flagg in William Wellman's screwball classic Nothing Sacred (1937).

She starred with Jimmy Stewart in Made for Each Other (1939) and brought Alfred Hitchcock briefly into the screwball fold for Mr. & Mrs. Smith (1941). Her final film, Ernst Lubitsch's To Be or Not to Be, combined screwball with wartime propaganda, and ended her career in the hands of yet another great director.

And while Preston Sturges only contributed to the treatment of Lombard's Love Before Breakfast (1936), you get delirious imagining the chance that he might have directed her during his golden moment that lasted until 1944. But that possibility – like many others – disappeared on that mountainside outside Las Vegas in early 1942.

As for Gable, he was the "King of Hollywood" by the time of the sensational success of Gone With the Wind, though it's hard to deny that few of the pictures he made after that did more than trade on his unassailable stardom. His last film, The Misfits, would be one of his best, though he never saw it, dying two weeks after filming wrapped. He was buried next to Lombard.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.