Guadalcanal Diary is the first real American combat document of World War Two, written by a war correspondent who had gone ashore with the Marines in the first U.S. ground offensive in the Pacific. Richard Tregaskis wrote it for an audience who were desperate to know what their sons, husbands, brothers and friends were experiencing as soldiers, fighting an enemy they probably hadn't given much though to just over a year earlier.

It's an actual diary, compiled from Tregaskis' notes, and amidst the accounts of encounters and movement and excitement and discomfort you'd expect from a diary, it has occasional moments of insight about what it's like to, say, emerge from your shelter after a bombing or an artillery barrage:

"When you finally get up to look around, you have butterflies in your chest and your breath is noticeably short and your hands feel a bit shaky. Those feelings do not seem to be avoidable by any conscious effort."

It's also full of the stoicism and strangely demure descriptions of combat, carnage and death you'd expect from a man of Tregaskis' generation (born in 1916) and the voluntary and involuntary restrictions of wartime censorship. Which doesn't mean it's free of passages that bring you up short with their vivid glimpses of a battle's aftermath:

"Everywhere one turned there were piles of bodies; here one with a backbone visible from the front, and the rest of the flesh and bone peeled up over the man's head like the leaf of an artichoke; there's a charred head, hairless but still equipped with blackened eyeballs; pink, blue, yellow entrails drooping; a man with a red bullet-hole through his eye; a dead Jap private, wearing dark, tortoise-shell glasses, his buck teeth bared in a humorless grin, lying on his back with his chest a mess of ground meat. There is no horror to these things. The first one you see is the only shock. The rest are simple repetition."

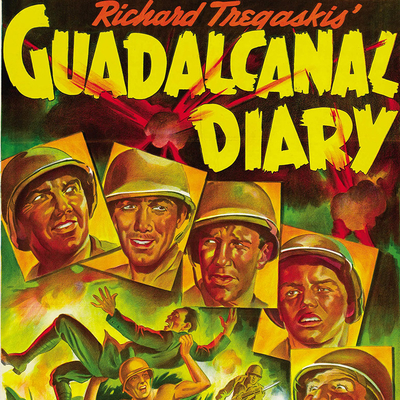

Guadalcanal Diary was published on the first day of 1943, a month and a week before Japanese forces finally retreated from the island, but by the first week of November that year 20th Century Fox had released a movie version of Tregaskis' bestselling book, just as eager to capitalize on the public's need to understand what this war looked and felt like.

Which they didn't – not really. What they wanted were reasons to understand that the cause these men were fighting and dying for was worth the cost, and like any decent propaganda that was what the film – and Tregaskis' book – tried to deliver. Nobody wants to see a film that looks and feels like an actual war, if that were even possible; only a masochist would willingly endure such a thing, and only a sadist could muster the craft to inflict it.

The film begins, as does Tregaskis' book, with the men on the troop transports sailing to an unknown destination, attending Sunday mass on the deck, singing "Rock of Ages." One soldier acknowledges another one's compliment on his voice by saying that he probably got it from his father, a cantor. This is democratic America going to war, differences set aside in the face of the momentous task at hand.

We pick out the men we'll follow in a roundabout way. There's the chaplain, Fr. Donnelly (Preston Foster) and the senior officer, Capt. Davis (Richard Conte). Lloyd Nolan plays Gunnery Sgt. Malone, career Marine, the sort of NCO it's understood holds together any combat unit. Corporal Aloysius "Taxi" Potts (William Bendix) represents Brooklyn and the Dodgers, while Anthony Quinn is deputized as the unit's obvious "ethnic", Pvt. Jesus "Soose" Alvarez. Richard Jaeckel is Pvt. Johnny "Chicken" Anderson, nicknamed for his "pin feathers" – the whiskers this baby-faced recruit is barely sprouting.

We even get a stand-in for Tregaskis, wandering among the troops and taking notes – Reed Hadley's unnamed war correspondent and the picture's narrator, though the portentous and purple voiceover screenwriters Lamar Trotti and Jerome Cady put into his mouth are nowhere to be found in Tregaskis' book.

In her book The World War II Combat Film, Jeanine Basinger compares a group of war movies released in 1943, the first year Hollywood was fully engaged in making pictures dedicated to the war effort, for audiences that weren't yet exhausted by years of war and turning their attention to the imminent peace. There's Guadalcanal Diary, along with Air Force, Immortal Sergeant, Stand by for Action, Crash Dive, Action in the North Atlantic, Bataan, Destroyer, Destination Tokyo, So Proudly We Hail, Corvette K-225, Sahara and Cry Havoc.

She recognizes that Bataan, a film about one of America's first major defeats at the hands of the Japanese, is "the seminal film", the first of these pictures totally devoted to combat, without distracting subplots involving romances or side quests or the home front. It is, like Guadalcanal Diary, a story without women – so much easier to do in the setting of the Pacific campaign than in one where sailors, airmen or troops return to a home port, fly out of a British airbase or train for their campaign in the English countryside.

Like so many of the films she cites – and inspired by what she considers the archetype, John Ford's The Lost Patrol (1934) – they bring together an apparently accidental cross-section of types in the task of defeating a mostly faceless enemy. Like the book, Guadalcanal Diary "captures a sense of the democratic amalgamation of the fighting men, characters who are brave, jaunty, funny, and who sing. Oh boy do they sing! 'Rock of Ages,' 'Genevieve, Sweet Genevieve,' 'Bless 'Em All,' and many more. It's the combat film Hit Parade."

Basinger writes:

"We know Guadalcanal Diary to be an on-the-spot-correspondent's account of an actual battle. And yet the story might as well have been thought up in Hollywood by someone who had never been there. Setting aside differences in military uniform and weapons, and thus the attendant differences in mission and type of combat, Destination Tokyo, Bataan, Air Force, Sahara and Guadalcanal Diary are the same movie."

She compiles not just a list of essential elements in their story but a table comparing these films point by point. Key is the cast: "A group of men, led by a hero," who "undertake a mission which will accomplish an important military objective." She describes these men:

"They are of different ages. Some have never fought in combat before, and others are experienced. Some are intellectual and well-educated, others are not. They are both married and single, shy and bold, urban and rural, comic and tragic. They come from all areas of the United States geographically, especially the Middle West (stability), the South (naivete, but good shooting ability), New England (education), and New York City (sophistication). Favorite states are Iowa, the Dakotas, and Kansas for the Middle West; California and Texas for recognition; and Brooklyn. (In the war film, Brooklyn is a state unto itself, and is almost always present in one way or another.) Their occupations vary: farmer, cab driver, teacher. Minority figures are always represented: black, Hispanic, Indian, and even Oriental."

This stereotypical grouping has persisted over the decades because it happens to be true, a representative cross-section that paints an accurate picture of American combat personnel, whether enlisted or drafted, abiding all the way from Bataan and Guadalcanal Diary to Band of Brothers and The Pacific, and through Korea, Vietnam, both Gulf Wars, Afghanistan and beyond, growing ever more "inclusive" especially after the desegregation of the US armed forces after WW2 and through decades of increasingly polyglot immigration.

The only changing element is class. By Vietnam there were frequent complaints that soldiering was being done by the working class and minorities while exemptions were given to the draft-dodging, college-bound middle class. It's why there's a persistent joke that no Vietnam picture can get released without "Fortunate Son" by Creedence Clearwater Revival on the soundtrack.

More recently military service has apparently become more middle class, with army pay post-9/11 being one of the rare exceptions to wage stagnation. What this means is outside my analysis of a film like Guadalcanal Diary, but I'm sure conclusions will be drawn. And let's not forget the addition of women to uniformed support and even front-line units, though the futuristic war movie is the only truly inclusive place if you go by films like Aliens, Battleship, Edge of Tomorrow or Battle: Los Angeles.

What's challenging, however, is figuring out just who the hero of Guadalcanal Diary is supposed to be. Over time Anthony Quinn's face has dominated artwork on DVD reissues of the film, mostly because Quinn is the only member of the cast who ascended to stardom and stayed there for decades after the movie was released.

But he was far down the credits when it came out, and his big break after years of playing henchmen and Indian braves had only happened with Blood and Sand in 1941 and The Ox-Bow Incident earlier in 1943. In any case Quinn isn't asked to portray Pvt. Soose as much more than lusty, cocky and capable, and while he escapes a massacre early in the picture, his death is rather perfunctory when it happens during the final battle.

Richard Conte could be a compelling hero or villain in the many film noirs he made subsequent to Guadalcanal Diary, but his Cpt. Davis is noble but dull, encumbered by the death of a friend and fellow officer early in the picture, and by the responsibility of keeping his men alive. Lloyd Nolan has a bit more to do as the gunny, and Richard Jaeckel (a mail boy at Fox when he was cast in the picture) is simply "The Kid"; his discovery of a whisker worthy of a razor is played up as more triumphant than Pvt. Anderson actually surviving to the end of the movie.

Which leaves William Bendix's Cpl. "Taxi" Potts, the film's cab-driving representative from the nation of Brooklyn, introduced as comic relief in the scenes he shares with gravel-voiced Lionel Stander as Sgt. Butch, the company cook. But after he's run out of Dodgers jokes, Bendix is allowed to grow into the film's stoic everyman; the screenwriters and director Lewis Seiler (Hell's Kitchen, Whiplash, The Winning Team) give him a crucial monologue while the men are huddled together in a bunker during a barrage:

"I'm no hero, I'm just a guy. I come out here because somebody had to come. I don't want no medals, I just wanna get this thing over with and go back home. I'm just like everybody else, and I'm tellin' you I don't like it. Except maybe I guess there's nothin' I can do about it. ... When you're scared like this, the first thing you do is start tryin' to square things. If I get out of this alive, I'll probably go out and do the same things all over again, so what's the use of kiddin' myself? The only thing I know is I ... I didn't ask to get into this spot. If we get it – and it sure looks that way now – well then I only hope he figures we done the best we could and lets it go at that. Maybe this is a funny kind of prayin' to you guys, but ... it's what I'm thinkin' and prayin'."

Guadalcanal Diary did well at the box office – better than Sahara but nowhere near as well as This Is the Army. Bosley Crowther of the New York Times called it "stirring and inspirational" and even "almost documentary real," though David Lardner of the New Yorker said it was "altogether too soft" on its Marines, and that it contained "every cliché known to man."

In his introduction to the Modern Library edition of Tregaskis' book, author Mark Bowden (Black Hawk Down, Killing Pablo) wrote that Tregaskis' war, "the one this book is about and the one that made him famous, had swept up the hearts and minds of an entire generation to an extent far greater than those of the generation in the sixties that protested the Vietnam War. In 1943, young men were called upon to risk far more than their legal standing or the threat of being tear-gassed on the Washington Mall."

Tregaskis was severely wounded in Italy but went on to cover the Korean War and the early space program, and would write two books about President John F. Kennedy's naval career, one of them for children. But times changed, and so did Tregaskis' reputation, according to Bowden:

"Guadalcanal Diary is war reporting before the relationship between journalism and the military acquired its modern edge in Vietnam, where reporters were compelled to record the growing disparity between what they observed and what the U.S. military said was true. Tregaskis lived to report from that war, too, and by then he was regarded as little more than an apologist for the military. His was a voice from a different era, one in which the government and especially the military was held in the highest regard, even if GIs did gripe about the food and baffling wartime bureaucracy."

The modern war film is obliged to be far more realistic than Guadalcanal Diary or Bataan, but most of the time they play out as a subgenre of the action film, with an unmistakeable element of LARPing for generations secure in the knowledge that real war will never touch them.

Which is why, when real war breaks out somewhere else in the world and gets broadcast on cellphones and social media with horrific footage shot in portrait mode, many young people can't seem to understand that it's real. Stirring speeches are made on TikTok by people oceans away from the fighting, and choosing sides is only a hashtag away since, after all, isn't everything just propaganda? Like so many other words, its meaning has been transformed since Richard Tregaskis began typing his notes into a book in a B-17 flying back from Guadalcanal.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.