When The Silence of the Lambs became a shock hit in 1991, the talking points anatomizing its out-of-nowhere appeal featured speculation that fascination with serial killers had gone mainstream, emerging from the world of tabloids and grimy paperbacks and z-grade slasher flicks. With the film's final shots, "the serial killer becomes an American gift to the world, a fragmentation bomb, ready to explode," wrote Amy Taubin, a great defender of the film, in an appreciative essay.

I would go a step further and say that, with a film whose secondary villain (but principal antagonist) is a renowned psychiatrist (albeit one locked away for heinous murders), and whose heroine works for the criminal profiling unit of the FBI, the real subject of director Jonathan Demme's film is how modern society encourages and enables insanity.

We had been living with the antihero for decades and this sort of mild sociopathy had become dated; every bored or maladjusted teenager imagined themselves as a rule-breaker and a truth-teller (I know I did) and being misunderstood had become a kind of superpower.

It was time for the debut of the psychopath hero.

The Silence of the Lambs was released in the midwinter doldrums of 1991, a sign that Orion, its producer, wasn't expecting much of this gory psychological thriller whose two stars weren't considered big enough to open a picture. Anthony Hopkins had actually given up on the idea of a movie career and was back in London doing theatre. (In any case the studio had bet all their resources on the neo-western Dances with Wolves at Oscar season the previous year.)

The film was based on a book by former journalist Thomas Harris, whose novel about a terrorist attack on the Super Bowl, Black Sunday, had been turned into a movie in 1977. Harris had introduced the character of the serial killer psychiatrist Hannibal Lecter with his 1981 book Red Dragon and returned to him again for The Silence of the Lambs in 1988.

Harris' book initially caught the attention of Gene Hackman, who partnered with Orion to buy the rights on the assumption that he'd direct and star in the picture. (Some sources say that Hackman was going to play FBI senior agent Jack Crawford, others that he would portray Lecter.) But when he received Ted Tally's script he decided that it was far too violent and let Orion buy out his share.

As in Red Dragon, the Lecter of Silence of the Lambs is technically an ex-serial killer, locked up for life in a high security mental institution, an object of curiosity for academics and investigators who try – and fail – to get him to cooperate. Jack Crawford (Scott Glenn) knows this, and with pressure growing for a break in the case of "Buffalo Bill", a serial killer on the loose abducting and skinning young women, he decides to send Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster), an FBI trainee, to interview Lecter.

Crawford guesses that Starling, pretty and bright, would appeal to Lecter's tastes, and sends her to his dank basement dungeon as bait – a throw of the dice that might turn up nothing. He warns her not to answer any personal question or allow Lecter "into your head" – advice she promptly ignores the moment she turns up in front of the plexiglass wall of his now-iconic cell, for a scene that's become one of the great cinematic first meetings.

Orion settled on Jonathan Demme to direct the picture. Demme had come up through Roger Corman's grindhouse academy with pictures like Caged Heat (1974) and Crazy Mama (1975), before making Melvin and Howard (1980), a perpetual favorite on the repertory circuit. He'd minted his hip bona fides by directing two performance films – the Talking Heads concert picture Stop Making Sense (1984) and the film of actor and writer Spalding Gray's one-man show Swimming to Cambodia (1987).

But he'd also proved himself to the company by making two modest hit comedies for them – Something Wild (1986) and Married to the Mob (1988). Demme, who had a loyal crew that he treated like family and valued loyalty, wanted to work with his Mob star Michelle Pfeiffer again in the role of Starling, but Foster had actively campaigned for the part after reading the book, going so far as to contact Tally while Demme and the studio were thinking about Meg Ryan and Laura Dern.

Casting Lecter was even more circuitous. Orion co-founder Mike Medavoy wanted Robert Duvall for the role, and Jonathan Demme approached Sean Connery. Other actors considered were painfully obvious choices like Robert De Niro and Al Pacino, and outliers like Dustin Hoffman, Derek Jacobi, Daniel Day-Lewis and Forest Whittaker. Finally, remembering Hopkins' performance in David Lynch's film Elephant Man (1980), Demme had the actor's agent send him a script and met with him for dinner.

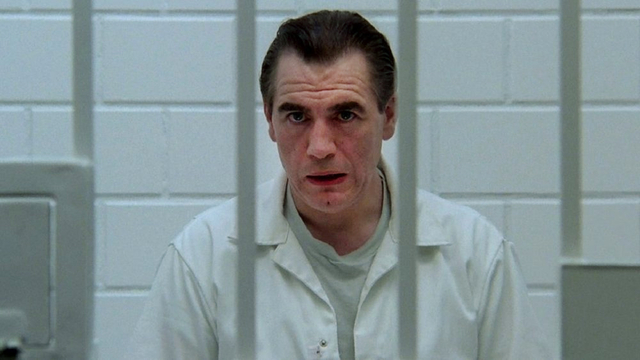

It's hard to imagine anyone else playing Lecter, even though at least three other actors have (and more are likely to in the future). There had already been an onscreen Lecter in Manhunter (1986), Michael Mann's adaptation of Red Dragon. Brian Cox had portrayed a far more physically intimidating Hannibal opposite William Petersen's FBI profiler Will Graham, and while it's fascinating to imagine an alternate universe where Cox's Hannibal returned for the sequel and became a pop culture icon, it's easy to see why it never happened.

While Demme's picture is essentially timeless – directed with the restraint you'd associate with the largely style-less '90s – Mann's film is wildly '80s stuff, of a piece with the Miami Vice high style look he helped create and painfully dated. While Hopkins' Lecter languishes in a stone dungeon that gives Demme's picture its first jolting dose of Gothic horror, Cox's "Lecktor" is locked away in a glaring, Kubrickian white-on-white cell.

Mann is far more interested in the "is-he-or-isn't-he?" psychosis of Petersen's Graham, and the monstrousness of Tom Noonan's serial killer, while Cox is confined to his white box, a pale but hulking spider at the centre of his web who still gives Hopkins a run for his money despite his brief screentime.

At first it looks like Demme is going to do the same thing and focus on his FBI protagonist while keeping Lecter locked away, a passive menace. One of the director's trademarks was having characters directly address the camera, nearly but not quite breaking the fourth wall, and it's used to great effect to make us feel how Clarice is always being looked at and underestimated at the same time.

"Don't you feel eyes moving over your body, Clarice?" Hannibal asks her during one of their meetings. "And don't your eyes seek out the things you want?"

We see Starling in sweaty gym clothes, the 5'3" Foster surrounded in an elevator by male FBI academy students in red golf shirts. The ambitious and repulsive Dr. Chilton (Anthony Heald), Lecter's captor, flirts with her, and Demme's camera pans around a room full of uniformed county deputies in a small-town funeral home as they size up and/or ogle Starling when she arrives to assist Crawford on a murder victim's autopsy.

Foster, just 28 when she made the film, was an old hand in the movie business with credits going back nearly two decades, highlights including Taxi Driver, Bugsy Malone and The Accused, which won Foster her first Oscar. She was reasonably concerned that the role and the award would typecast her in victim roles, so she worked hard to make sure Clarice was a suitably complex character who commanded her time onscreen – a tough job when you have to share scenes with Hopkins' Lecter.

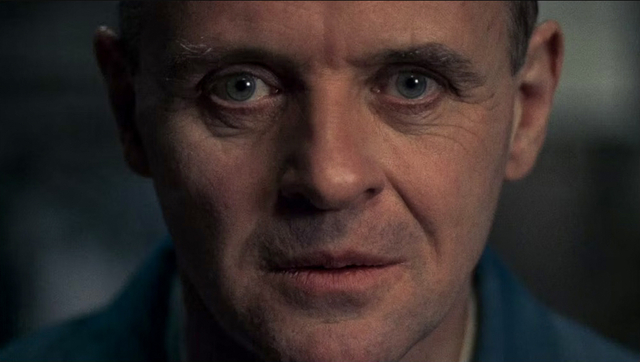

In retrospect it seems obvious that Anthony Hopkins would eventually find a role that would focus his considerable talent onto a star-making vehicle, but it certainly didn't seem likely to the actor at the time. Born Welsh, working-class and somewhere on the then-undiagnosable autism spectrum, the actor made a reputation for himself on stage and television playing everyone from David Lloyd George to Hitler.

Standout performances in films like Magic (1978), The Elephant Man (1980) and The Bounty (1984) marked him as an actor's actor but not a movie star. That was a role he assumed in that first scene with Foster in Demme's film, when he delivered one of the most meme-able lines in movie history (the one about fava beans and Chianti) and followed it up with a hissing chatter as he sucked his breath in through his teeth that made Hannibal Lecter come alive.

With one outlandish ad-lib Hopkins created a movie monster without the aid of special effects, but he was far from a bloodthirsty beast. We learn, in a single scene, that Lecter outmatches any one of his opponents, including Crawford and Starling and especially Chilton, and that the only reason he's safely behind bars is himself: as Petersen's Graham tells him in Manhunter (and Edward Norton's Graham in Brett Ratner's 2002 remake, which returned to the original title, Red Dragon), Lecter is working from a disadvantage: "You're insane."

Hannibal is, in the words of Mick Jagger, "a man of wealth and taste": a gourmand and world-traveler with refined taste in music and impeccable manners. (In Harris' later novel Hannibal, published in 1999, he says that he "prefers to eat the rude.") When a crazed psychopath in an adjacent cell violates and humiliates Starling as she walks past his cell, Lecter is heard whispering to him for the rest of the afternoon, after which the man dies swallowing his own tongue.

Hopkins recalled later how Demme told him that Hannibal was "a good man locked inside this insane mind," and Kari Lemmons, the actor, writer and director who plays Starling's Quantico roommate Ardelia, mused in a bonus feature included with one Blu-ray reissue of the movie that "you want him to get away."

By contrast the active serial killer in the film comes from a more familiar, mundane place. "Buffalo Bill", aka Jame Gumb as played by Ted Levine, is a composite of actual serial killers like Ed Gein, Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy and the more obscure Gary Heidnik.

Their names assumed a celebrity aura thanks to morbid pop culture enthusiasts and the pre-internet edgelord "atrocity collectors" who seemed to proliferate in the aftermath of the Manson Family murders. Levine would refer to them as "Gloomers", and their avid collection of real-life crime trivia and artifacts would provide fodder for commentators and academics who tried to explain The Silence of the Lambs after the film rocketed to the top of the box office.

It's ironic that critics like Amy Taubin would describe the serial killer as a uniquely American phenomenon; a list of serial murderers ranked by number of victims features killers from South and Central America, India, Pakistan, Russia and China before the first American entry, and that's the relatively unknown Samuel Little.

You need to scroll down over two dozen places before reaching Gacy, whose tally is nowhere near close to Luis Garavito or Pedro Lopez, who are both estimated to have over three hundred victims. It's time for America to decolonialize the work of marginalized serial killers from the developing world.

Gumb's latest victim is Catherine (Brooke Smith), the daughter of a US senator, who's introduced singing along to Tom Petty's "American Girl" as she drives home at night. (Demme is never subtle with his signifiers.) Gumb is piecing together a skin suit made from young women he abducts and starves for three days before killing, and the clock starts ticking the moment her kidnapping becomes news.

Levine's Gumb – a fantastic performance, overshadowed only by Hopkins and Foster – is obsessed with transformation and cross-dressing; a transvestite but, as Lecter (and Harris and Demme and Levine) is at pains to point out, not a real transsexual but something "more terrible".

It's no surprise that Buffalo Bill was controversial with the publication of Harris' book and (especially) once Demme's film became a box office hit. It's even less of a surprise that it remains controversial today, and the recent CBS TV spin-off series Clarice has been at pains to "rewrite the complicated legacy of Starling" in the words of one executive producer, casting trans actor and activist Jenn Richards as an FBI informant.

What's certain is that nobody would make The Silence of the Lambs the same way today (and there's every indication that this still-hot intellectual property will get re-made). Demme's film is, despite the avowedly liberal director's years of subsequent apologies, considered problematic, and destined to be consigned to that catalogue of films ranging from Breakfast at Tiffany's, Sixteen Candles and Manhattan to Song of the South, Gone with the Wind and Birth of a Nation.

And all this in a film that was at pains to cast its heroine as the story's knight in shining armour, on a quest to save the damsel in distress, as it's frequently described by fans. (And despite that damsel, Catherine, screaming with rage at Starling when she arrives to rescue her – alone, with Crawford and his heavily-armed task force four hundred miles away: "Don't you leave me alone you fucking bitch!")

Clarice's rescue of Buffalo Bill's last victim and vanquishing of the monster (who dies curled up like an insect on his back) is heroic, but it isn't depicted with the same panache or spectacle as Lecter's own escape from custody. From the moment Clarice arrives in front of his cell Hannibal carefully manipulates her, Crawford, Chilton, the FBI and ultimately the whole US government to provide him with a chance at freedom.

He does it in a heart stopping sequence that involves killing two police officers, skinning the face off one while gutting the other and leaving him strung up like an obscene trophy bird on the bars of his holding cell – lit with suitably Gothic drama by cinematographer Tak Fujimoto. That he also kills an ambulance full of paramedics and a tourist in an airport is a footnote to his flamboyant breach of a prison built by (the implication is undeniable) comparative mediocrities.

When her roommate tells her about Lecter's jailbreak, Clarice is unconcerned about her own safety, sure that Lecter will never come after her: "He would consider that rude." Because the payoff comes in the final scene when, moments after collecting her badge and a (perhaps not entirely) fatherly congratulation from Crawford, she gets a phone call from Hannibal.

He's in disguise, in a blonde wig, white suit and straw hat, outside the airport on a tiny Caribbean Island. (Bimini, it turns out.) He reassures Clarice that she's safe ("The world is more interesting with you in it.") before telling her that he's "having an old friend for dinner," hanging up and jauntily following Chilton as he leaves his plane and heads for what he obviously thinks is a safe place.

It's meant to be a wry rimshot of an ending as Demme has pointedly painted Chilton to be far less sympathetic character than Hannibal – a rude man who harasses young women and deserves his punishment, horrible as that might be. Let's just ignore those cops, who seemed perfectly nice, and those paramedics, and that tourist. And that poor census taker who provided the mains that Lecter served with that side of fava beans.

I'm not sure that Demme ever apologized for making a psychopath so sympathetic, but there's no other way to describe the most salient achievement of The Silence of the Lambs. This was probably inevitable the moment he cast Hopkins in the role; the actor has a unique talent for inhabiting characters by using both endless invention and the peculiar charm that defines his onscreen persona. I can only speak to my own brief time spent with the actor in a hotel room and an elevator, but the lasting memory is of a gentle but prodding curiosity, and his evident enjoyment in the whole process of being a movie star, even in the Groundhog Day grind of a film festival.

The Silence of the Lambs pulled off a rare sweep of the top five awards at the Oscars, the first film to do it since One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest in 1975, only one of three in Academy Awards history, and the first horror film to manage anything like this acclaim. Demme, Harris, Tally, Foster and Hopkins had made a horror movie that appealed to people who carried tote bags from their local PBS affiliate.

And it created a "Lecterverse": Harris became fascinated by his creation, going on to write Hannibal and Hannibal Rising, and penning the screenplay for the 2007 movie version of the latter. I've mentioned the 2002 re-make of Red Dragon, which starred Hopkins, who also reprised the role in Hannibal (2001), a lurid grand guignol directed by Ridley Scott and starring Julianne Moore as Starling – a very telling bit of miscasting.

As fine an actress as Moore can be, she's far more glamourous and far less vulnerable than Foster, and in any case Harris utterly betrayed the character by having Lecter brainwash her into both companion and accomplice, the two of them disappearing at the end, presumably for future happy hunting grounds.

But the appetite for Hannibal tales onscreen remained, and Peter Webber's 2007 Hannibal Rising gave us his backstory – born of Baltic aristocracy and traumatized into muteness by Nazi and Soviet invaders during the war, young Hannibal (Gaspard Ulliel) is a brilliant psychopath who kills for revenge. (And who deserves to die more than fat bullies and Waffen-SS killers in hiding?) It's a dismal piece of work, all the worse as the reclusive Harris had an active hand in the thing.

The NBC TV series Hannibal brought the character back again in 2013, with Mads Mikkelsen as Lecter in a prequel that encompassed many of the characters and events of Red Dragon, with the inevitable race- and gender-swaps. The series had a cult following and was celebrated for its brilliant camera work and art direction, but it struggled to attract viewers and was canceled in 2015.

Finally CBS debuted Clarice in 2021 – a sequel to The Silence of the Lambs imagined as the sort of police procedural the network has refined to widget-like predictability. Rebecca Breeds is a Starling who's emerged from the Buffalo Bill case more vilified than celebrated, suffering from PTSD and delirious with flashbacks. It has struggled to keep an audience with headlines like the one in Entertainment Weekly: "Clarice doesn't have any brains worth chewing."

"Foster's Clarice battled personal demons and professional animosity, too," writes EW's Darren Franich. "But she was also cool as hell, slyly undercutting all preening patriarchs, visually dominant even when she was a foot smaller than every man in the elevator. Breeds subtracts all the swagger from the sorrow, a decision that matches Clarice's colorless visual palette."

Conspicuous by his absence in Clarice is any mention of Hannibal Lecter by name. (The character is a trademark of the Dino de Laurentiis Company, while rights to other characters from the Lecter saga are owned variously by MGM, Gaumont International and Harris.)

And while Hopkins has been adamant about not returning to the character (unless he's tempted with unspeakable amounts of money), there are persistent rumours of a Silence of the Lambs reboot, probably as a miniseries, likely on a quality streaming service that can show the gore networks aren't allowed to, even today. It's doubtful that Buffalo Bill will return as anything resembling a trans character; he'll probably be a Republican.

But the damage has been done. The character of Clarice Starling has been reimagined and abused even by her own creator, and we have no shortage of righteous psychopaths – like Dexter Morgan, Benedict Cumberbatch's Sherlock Holmes, Joaquin Phoenix's Joker, almost anyone in a Quentin Tarantino film, Mike Ehrmantraut, and most of the characters in The Sopranos or Yellowstone – who can maim and kill as long as their victims are deemed sufficiently evil – or rude. This is not a good place to be.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.