Terence Davies died this week at his home in Essex, of cancer. The director had a great career for a late bloomer, putting out a film every few years, working with actors like Gena Rowlands, Gillian Anderson, Rachel Weisz, Tom Hiddleston, Cynthia Nixon, Jennifer Ehle and Peter Capaldi. His last movie came out only two years ago, and as far from the mainstream as his pictures were, Davies definitely did not die in obscurity.

Back when I still saw movies at film festivals, Davies made one of the most emotionally powerful and evocative pictures I had ever seen – a film that resonated with some buried, ancestral memories I wasn't aware that I even had at the time. That film – backed up by its "sequel", released just four years later – is still recalled as one of the most notable and assured directorial debuts ever, in Britain or elsewhere. But until I read about Davies' death this week, I had nearly forgotten about it.

Thankfully Davies didn't have to rely on people like me to safeguard his reputation for posterity.

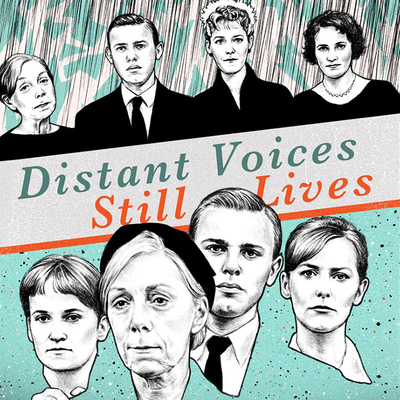

Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988) is really two films, shot two years apart, with the same actors telling the story of a working-class family in Liverpool during and after World War Two. Distant Voices begins outside a terrace house in the rain where a woman comes out to collect three bottles of milk from the stoop, and as the camera slowly follows her through the door we hear, first of all, the Shipping Forecast on the radio. We are in working class Britain, at a time in close proximity to the war.

An adult voice calls three children to come down and get ready for school, and then a woman begins singing "I Get the Blues When it Rains," originally recorded by Big Bill Broonzy. This gives way to the soprano Jessye Norman singing "There's a Man Goin' Round Takin' Names," by which point the camera has entered the house and turned around. The rain has stopped, and we see a hearse drive past the door, and the camera settles on a family dressed in mourning; they pose somberly for the camera in front of a photo on the parlour wall of a man holding a horse's reins (a photo of Davies' own father) and then walk out the front door and into a black car that follows the hearse down the street.

We see the family again, posing in the same spot, but dressed for the wedding of oldest daughter Eileen (Angela Walsh) on her wedding day. It's a Kodak moment; I remember many ones like it – a group photo in some place where the light reliably produces a decent shot (in my family, who worked for Kodak and lived just a few blocks from its Canadian factory, it was a spot in the backyard by a lilac bush). Eileen says that "I wish me dad was here." The camera pans to her sister Maisie (Lorraine Ashbourne) whose internal voice replies "I don't."

These are the Davies, modeled (obviously) on the director's own family, but imagined at a time before his existence. Besides Eileen and Maisie there's Tony (Dean Williams), their mother Nell (Freda Dowie) and father Tommy (Pete Postlethwaite). Their story will be told in a gradual, almost swooning fashion, with flashes back and forward, and for most of Distant Voices it's lived in the shadow of Tommy's unpredictable rage.

We get glimpses of that rage. Maisie begs for permission to go to a dance; her father tells her she can't until she washes the basement floor. As she finishes she asks him if she can go now; he tosses a handful of coins on the ground, then beats her savagely with a broom handle. Hard upon that we see Tony in an army uniform, drunkenly smashing the front window of the house, daring Tommy to come out and fight with him.

He holds two beer bottles in his bleeding hands while he asks his father to have a drink with him. The military police arrive and drag Tony, obviously AWOL, away in a van. A later scene shows Tommy as a boy, kicked out of the house as punishment by his father, retreating into the darkness down their street while Nell cries silently in the window above.

We get no explanation for Tommy's fury. The modern mind suspects bipolar disorder, and a brief scene later hints that his madness might be passed down when we meet his brother Ted, an apparently simpleminded, grown man living with their mother, whose lunacy appears more gentle.

In Catholic, working-class Liverpool, Tommy's rages are dismissed as parental strictness, technically admirable, though his violence would have been harder to excuse. (On my own Canadian, working-class street it would have been discussed quietly, judged but not interfered with, even if it marked the family with a stigma: a weak man, pity his wife and children.)

But Davies and Postlethwaite are at pains not to make Tommy a complete tyrant. In one scene, after the children barely make it to a bomb shelter while sirens go off and Luftwaffe bombs start to fall (Liverpool was the second most bombed city in Britain), he snaps at them and slaps Eileen, before hugging the girl and asking her to sing "Roll Out the Barrel" to help calm the terrified crowd huddled in the bunker.

In another one we see Tommy hang decorations on the tree in the corner of the parlour; he creeps into the room where his three children sleep in one bed, muttering "God bless, kids" as he hangs a Christmas stocking on the bedpost. But the next scene shows him sitting silently at the table with them, cake and Yule log on the tablecloth with the china and silver, as his hands begin to tremble. He gathers the linen between his fingers and pulls everything onto the floor before bellowing for Nell to clean it up.

Whether Davies intends it or not, Tommy's violence is just one thing among many that make working class life dangerous. Nell sits on the ledge of an upstairs window cleaning the glass while her children watch from below, whispering a prayer that their mother doesn't fall. Tommy corners her in the hallway of their home, beating Nell and screaming "Shut up!" as she cowers and cries. The camera pans down from her face to her arms, taking in every bruise, while she polishes the sideboard.

The children climb into the hayloft of a stable to spy on their father as he grooms a horse, singing "Danny Boy" while he firmly but gently combs the animal's coat. After he's dead, the children ask Nell why she married him. "He was nice," she says. "He was a good dancer."

Davies was only seven when his father died of cancer after two years' illness; Distant Voices is composed from the memories of his older siblings, which is why his film weaves back and forth in the timeline, to points before and after Tommy's death, delirious as it vaults across the years, though never random. At the farthest end is Eileen's wedding, not long after her father's death.

The director was never allowed to watch movies while his father was alive, so his most vivid childhood memory is seeing Singin' in the Rain. Davies was avid about his love for Hollywood musicals (he endeared himself to me forever with his constant praise for Doris Day) so it might come as a shock to anyone who's read my rough synopsis of his film so far that Distant Voices, Still Lives is far closer to a musical than any sort of northern kitchen sink realism.

It's stylized like the best musicals, celebrating the artifice of moviemaking; the cast pose for the camera in tableaux and address the lens directly (while never actually breaking the fourth wall). And it's full of songs: over the course of its nearly 90 minutes we're treated to "Oh, Mein Papa", "Up the Lazy River", "Galway Bay", "Taking a Chance on Love", "My Yiddische Mama", "Brown Skin Girl", "Buttons and Bows" and many other tunes, from suitably period recordings or sung by the Davies' family and friends at parties or (most of all) in the pub.

Davies masterfully conveys a sense of place. Some of us might recognize with a shudder how delineated, even claustrophobic, life was for working class men and women. The children, at least while young, are allowed more chances to roam, but as soon as they're teenagers the scope of their world begins to shrink.

First of all there's the family home – the classic "two up, two down" Victorian brick terrace house, whose parlour is the venue for every holiday, wedding and funeral. There's the church, of course – a sacred space, to be treated as such. (Informal spaces like the church basement or parish hall were an innovation more common in the New World, to be discovered after emigration.)

And there's the pub – the opposite of sacred, cramped and hot and, in Davies film, a song-filled performance space as much as a place to enjoy a pint, a shandy, a Black and Tan or a Rum and Pep. Once a year there might be a day out, to New Brighton or even Blackpool, crowded on all but the coldest, wettest days.

Closest of all is the stoop. The Davies are lucky – with a bay window at the front of their house, they have a few square feet between the front walls and the low brick fence to get some air, smoke or leave a baby in a pram without standing right in the street. Critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, writing about the film not long after its release, said that "the film regards this zone as a kind of privileged site — not quite the world outside the house, but still free of the sense of confinement inside."

(For my mother's family, leaving Merseyside for Canada, there was the sudden prospect of front and back yards, grassy schoolyards and public parks whose use was actually encouraged. My grandfather built our local church and its basement, and later sat for days watching the workmen demolish his work to build a new, bigger one.)

The slow constriction of space and potential affects Eileen the most. Blessed with glamourous good looks, she's the sibling who escapes most of her father's wrath and carves out scant but cherished leeway thanks to her boisterous friend Micky (Debi Jones), who has found a way to charm Tommy denied to his children.

Eileen, Micky and their friend Jingles (Marie Jellman) manage a summer away, working as waitresses in a hotel in Pwllheli, the Welsh seaside town, but Tommy's illness forces Eileen to cut her summer short and return home. One of our final glimpses of her father is when he appears without warning at the front door, gaunt and zombie-like, after checking himself out of the hospital to make it home for her wedding.

Much as Davies remembers his childhood, there's a sudden change of mood after Tommy's death, reflected in Still Lives, the second half of the film. Eileen, we learn, has married an oaf, and like Jingles before her and Micky afterward, have their friendship challenged by the demands of husbands who are only scant improvements over fathers like Tommy. (Maisie has fared better, marrying a man who treats her with more affection than bullying.)

No longer children, their world has shrunk, and with a national housing shortage they find themselves either living with Nell or Tommy's mother. Parties and the pub – with children being born and christened, they frequently gather to "wet the baby's head" – offer rarer escape now, and the pub sing-a-longs have a desperate mood. Near the end of the picture we hear someone say "put on a record" during Tony's wedding party, and shudder as we realize that those evenings of song will soon end forever.

On the surface, the story of the Davies family in Distant Voices, Still Lives sounds dire, so why did I find it so captivating thirty-five years ago, when I saw the film's debut at the Toronto film festival? Yes, the basic narrative sounds pitiless on paper, but the way Terence Davies recreates it is unexpectedly lush and vivid, in spite of its muted hues of brick stained with coal smoke and faded wallpaper in tiny rooms.

As Jonathan Rosenbaum said in his essay, "the awesome strength of Distant Voices, Still Lives as a whole is that it makes every moment necessary and indelible as well as beautiful."

"I'm not trying to deny that the characters in Davies's film suffer a great deal as well; indeed, one believes in their suffering in a way that one doesn't believe in the assorted woes of the characters in the other movies," he wrote, celebrating "how much, in fact, we're able to luxuriate in their fleeting yet ecstatic happiness in spite of all their grief. The sheer physicality of their songs, their laughter, their smiles, and even on occasion their tears makes one feel grateful to be alive; by contrast, even some of the more exciting moments in Indiana Jones and Batman make one feel like an invalid on sedation getting jolts of electroshock."

Even if emigration spared me growing up Merseyside in a terrace house or a council flat, I recognized the stoicism of the Davies family, the use of sarcasm and even insults to temper affection, and the real pain suddenly and nakedly visible when emotions escaped. Near the end of Distant Voices it's Eileen, crying helplessly in Tony's arms outside her wedding party, sobbing that she misses her father. This is echoed in Still Lives with Tony on the street outside his own wedding party, bawling painfully but alone. Davies might have denied us conventional story and structure with his film, but he made up for it with characters and real emotional power.

Up until Distant Voices, Still Lives was a huge hit on the festival circuit, Davies was just a struggling experimental filmmaker who started his career late in life, known for three short films. After it he should have been able to write himself a ticket to Hollywood, but he chose to follow up with The Long Day Closes (1992), a sequel of sorts set in another Catholic working-class Liverpool family, but focused on a boy obviously meant to be the filmmaker.

He had a bigger budget this time, and produced a picture full of even more bravura sequences, like the long overhead tracking shot from street to church to school and beyond, set to Debbie Reynolds singing "Tammy". If you were hungry for more from the world of Distant Voices, Still Lives it was worth the wait, but the extra polish put a stylized distance between the viewer and the characters wholly lacking in his first feature.

After that he was known for literary pictures. The Neon Bible (1995) was based on a John Kennedy Toole novel and starred Gena Rowlands, and The House of Mirth (2000) starred Gillian Anderson in an adaptation of an Edith Wharton book.

His career misfired after that, and Davies was sure it was over when he made Of Time and the City (2008), his first and only documentary, for that year's celebration of Liverpool as a European Capital of Culture.

While occasionally ponderous, the film is an audacious (and occasionally cruel) love letter to his birthplace, full of striking sequences like the one depicting slum clearance and the rehousing of families into tower blocks, scored to Peggy Lee singing "The Folks Who Live on the Hill." He revisits those high rises later in the film, in the '70s, when they had become horrible vertical slums begging for demolition, testaments to the arrogance of architects and planners.

"We had hoped for paradise," Davies intoned in his narration for the film. "We got the anus mundi." (Like Davies' childhood home, the Birkenhead dockside tenement that was my family's last address in Britain didn't survive either the Luftwaffe or postwar urban renewal. In any case I have to be grateful to my grandfather Murphy, whose decision to leave spared me a childhood likely spent in one of those tower blocks.)

Of Time and the City was a huge critical success and gave Davies a fine last act for his career. The Deep Blue Sea (2011) starred Rachel Weisz and Tom Hiddleston in a story based on Terrence Rattigan's play, and The Sunset Song (2015) finally gave Davies the chance to film Lewis Grassic Gibbon's 1932 novel after trying and failing two decades earlier.

The biopic A Quiet Passion (2016) starred Cynthia Nixon as the poet Emily Dickinson, and Benediction (2021) featured Jack Lowden and Peter Capaldi as the war poet Siegfried Sassoon early and late in his life. They were all critical successes, and though none of them would earn a single weekend's box office on a Marvel picture (despite starring actors with berths in the MCU), they allowed Davies to stake out a spot in proud opposition to blockbuster filmmaking – one I'm sure he would have cherished. For a man who lived to make movies, that looks like a triumph.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.