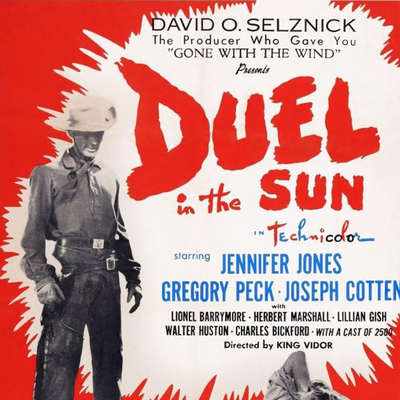

Variety's review of King Vidor's 1946 western Duel in the Sun refers to Gregory Peck taming "a sex-maddened stallion." If you've seen the film you might struggle for a moment to remember precisely what scene this was, as most of the film can be described with the phrase "sex-maddened," so much that the picture quickly gained the nickname "Lust in the Dust."

The film's reputation as a (doubtless unintended) camp classic led to Paul Bartel making a loose parody of it in 1985 using Vidor's film's mocking nickname as his title, with the transvestite Divine starring alongside onetime matinee idol Tab Hunter. And yet Bartel's movie never manages to be more outlandish than Vidor's original, no matter how hard it tries.

From the outside Duel in the Sun looks like a western: there are cowboys and railroads and cattle barons and saloons and six-shooters and ranches and gunfights under the blistering sun. But there's so much more going on under the hood – a Rube Goldberg contraption of genre and style built of lurid Technicolor that makes most of John Ford (My Darling Clementine was released the same year) look like Samuel Beckett.

The film begins with a musical prelude by Dimitri Tiomkin, followed by an overture over which a narrator (none other than Orson Welles) tells us how "a grim fate" awaits "the transgressor against the laws of God and man," amidst a great deal of editorial explanation of what we're about to see. Most important of all we're told that the head-shaped rock ponderously overlooking a desert landscape we've been staring at all through the prelude is called Squaw's Head Rock, and that it's part of a native legend about a pair of tragic lovers lost in the desert, and a flower that only blooms there – "quick to blossom and early to die."

In case we might not make the connection, the frame dissolves from the flower to the face of Pearl Chavez (Jennifer Jones) as she dances on the street outside some vast border pleasure palace, a den of vice whose principal entertainment is her own mother (dancer Tilly Losch), whose sultry performance on top of the bar ends when she leaves the casino in the arms of a man who, only seconds before, had been luridly appreciating Pearl's own dancing skills.

Pearl's father Scott (Herbert Marshall), a faded creole aristocrat, gets up from losing his money at the card table to follow the pair, pausing only to tell Pearl to go home before gunning his wife and her lover down. In a cell awaiting his hanging, he tells his daughter that he's arranged for her to live with an old flame of his, a second cousin named Laura Belle McCanles (Lillian Gish) married to a rich Texan whose honorific "the Senator" may or may not have come with an elected office.

Because in Texas during its frontier heyday men like the Senator are the law, presiding over his million-acre ranch, Spanish Bit, like a lord in his manor. Pearl gets off the stagecoach in the town of Paradise Flats ("The Paris of the Pacos" as a sign helpfully informs us) where her rough manners and mixed-race beauty gets her all the wrong kind of attention. Used to this sort of treatment, she tries to brush off the Senator's oldest son Jesse (Joseph Cotten) who had been sent to collect her. After a long ride through the wilderness they arrive at the McCanles' huge hacienda as the setting sun colours the air around them a fiery ochre.

She's met warmly by Laura Belle, who insists that Pearl will be treated like her daughter, and with less hospitality by the wheelchair-bound Senator (Lionel Barrymore), who only sees her race and his memory of her father, his onetime rival for Laura Belle. Finally, she meets the McCanles' younger son Lewt (Gregory Peck), a bad boy and the apple of his father's eye; as they leer at each other we have some idea who'll end up lost in the shadow of Squaw's Head Rock.

King Vidor – his real name – was one of the giants of American cinema in the decades straddling silent and talking pictures. Born to a wealthy Galveston family, he directed his first picture in 1918, and his first undisputed masterpiece with the war movie The Big Parade in 1925. Influenced – like most ambitious directors at the time – by D.W. Griffiths, he incorporated elements of German expressionism into The Crowd (1928) and developed a reputation for working well with actors, like Lillian Gish in La Boheme (1926), Marion Davies in Show People (1928), Barbara Stanwyck in Stella Dallas (1937) and Robert Donat in The Citadel (1938).

Vidor was one of the uncredited directors on The Wizard of Oz (he directed the sepia-toned Kansas scenes and the "We're Off to Meet the Wizard" number) and called producer David O. Selznick a close friend, which is how he ended up being presented with Duel in the Sun, a best-selling novel by Niven Busch that Selznick had bought the rights for, intending it as a vehicle for his then-mistress Jennifer Jones.

(Niven Busch had a great story; a journalist in New York City, he was working for Time and the New Yorker when he realized his career had probably peaked so he went west and started writing scripts. He got an Oscar nomination for In Old Chicago (1937), based on his own short story, and went on to do screenplays for The Westerner (1940), The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), and Pursued (1947). He was married to actress Teresa Wright, the third of five wives, and started writing novels between scripts, including The Furies, which Anthony Mann made into a movie in 1950. He retired to ranching and teaching but would play a cameo in The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988), made three years before his death.)

Selznick had sold Vidor on Duel in the Sun by promising not to interfere with the production. Talking to Richard Schickel for The Men Who Made the Movies, Vidor recalled that "I saw it as a possibility for an intense new angle on a western situation – a small, really small frame. He said no big stuff. But as we got into it, he wanted me to run Gone with the Wind and he wanted to have the biggest ranch and the most cattle and the biggest cast and the script was being rewritten and he suddenly had the idea this should be another Gone with the Wind of the West, you know. And it was a question of blow up, blow up, expand, expand, expand. In fact, the beginning, the opening shots, I didn't shoot – you know, the big Mexican border dance hall – but he had become the writer then and it just got blown up all out of size and a long way from that intense little study."

Vidor walked off the set on the second last day of filming, and parts of the picture were actually made by a team of assistant directors that included Josef von Sternberg, William Dieterle, William Cameron Menzies, Otto Brower, Sidney Franklin and Selznick himself, in addition to two second unit directors. In the end production took over a year and a half, the final budget rumoured to be over $6 million.

And it shows onscreen, in scenes like the one where the Senator learns that a railway crew is approaching the border of his ranch. He puts a call out for his ranch hands to saddle up and arm themselves, and we see an army of riders converging from every direction, riding along ridges and charging down steep hillsides to meet the workmen laying track right up to the barbed wire fence. Vidor told Schickel that he was happier shooting 3,000 actors than just two, and the scene is of a piece with similarly epic ones he'd directed in The Big Parade, The Crowd and Our Daily Bread (1934).

Up to this point in the film the two brothers have been competing for Pearl's attention, with Jesse promising her a better life as a lady, while Lewt offers little more than carnal fulfilment. Jesse admits that he's on the side of the railway, dismounts and prepares to cut the barbed wire. With the Senator's cowboys lined up on one side of the fence, preparing to fire on the railway coolies, the cavalry (literally) rides to the rescue, drawing up on the other side behind the stars and stripes. The Senator, who once fought for the Union, admits defeat, but disowns his older son, banishing him from Spanish Bit.

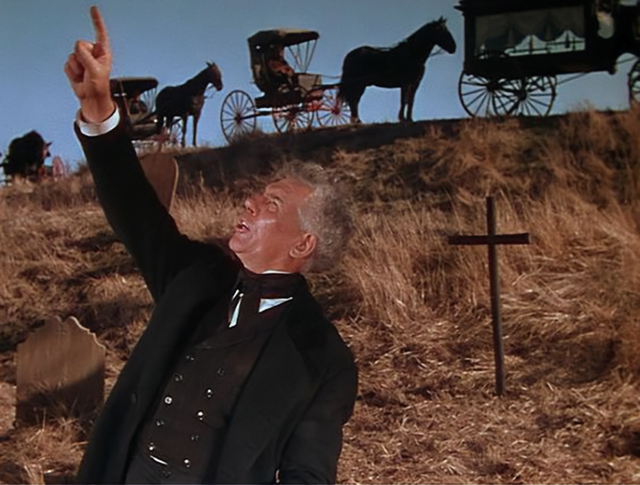

With Jesse still on the ranch, Pearl insists over and over that "I want to be a good girl," and Laura Belle calls on Jubal Crabbe, the Sinkiller (Walter Huston) for assistance. The Sinkiller is a gun-toting evangelical mercenary, the sort of man of the cloth who thrives in a Wild West where no Episcopal minister dares to tread. Wrapped only in a Mexican blanket, Pearl is summoned to the drawing room in the middle of the night for Crabbe's exhortations to virtue.

Huston tears into the role of the Sinkiller like a hungry man at a Vegas buffet, flashing his pistol and laying on hands; it's a performance that will echo in later films like Elmer Gantry and The Night of the Hunter – the (un)holy man, full of undeniable charisma but questionable motivation, and for a moment it's possible to see Vidor's film as less a western than an intimation of some gothic morality tale that would evolve from the western's bones.

But with Jesse gone Pearl is drawn to Lewt helplessly, two lust magnets whose poles pull them together. In The Western From Silents to the Seventies, George Fenn and William Everson write how sex made its way into the western in the aftermath of Destry Rides Again (1939) and especially The Outlaw (1943). They write that D.W. Griffith, who died in 1948, "was a frequent visitor to the set, and he and Vidor must have had some wry comments to make on the subordination of spectacle – of which they were past masters – to the titillations of sin and sex!"

Everson and Fenn are sure that the film's prestige production pedigree – top rank director and producer, stars, writing and score – helped get it past the Hays Code to an eager audience in ways that the "much cruder" The Outlaw didn't. You could argue that the Code inevitably meant that you'd get films like Duel in the Sun, much as you'd later get A Summer Place, with every picture between them doing their bit to erode the power of the Code as producers and directors strove to deliver the sex that they knew audiences wanted, with varying degrees of wit, artifice or earnest declarations of striving for a frank "social message."

There are not one but two rape scenes between Jones' Pearl and Peck's Lewt at different points in the picture, notionally ameliorated by her protests turning into acquiescence, then shame. Pearl increasingly insists that she's "trash – like my ma," suggesting that her erotic corruption is even more bred in the bone than Lewt's compulsions to gamble, brawl and fornicate, which his parents insist is their fault for spoiling the poor boy.

And Peck's Lewt is an incredibly capable rogue, a tough cowboy who can break that "sex-maddened stallion" when nobody else can and ride a herd of wild horses right into a stockade. Left to each other in the atmosphere of the lawless West the Senator once ruled, he and Pearl might have found a raw sort of happiness, but it's the impending civilization of that West, symbolized by the railroad and Jesse's law degree and the government down in Austin, that seems to encourage Lewt to toy with and discard the socially awkward, mixed-race Pearl.

And if there's any lightning rod for criticism of Duel in the Sun it's Jones' performance as Pearl. Selznick might have wanted to make the picture a showcase and tribute to the woman he'd eventually marry, but her Pearl, covered in a full-body fake tan, is allowed to chew more scenery than Huston's Sinkiller.

At her most wanton, Pearl employs the same breathy voice that Marilyn Monroe would use in her rise to stardom, and her convulsive response to Lewt's brutal attentions often resembles possession, Jones writing on the ground in hard shafts of moonlight. Jones was not a terrible actress; her Academy Award for The Song of Bernadette just three years earlier is proof of that. She'd play a charmingly naïve heroine for Ernst Lubitsch in Cluny Brown the same year, and a superior variation on the wild child for Powell and Pressburger in Gone to Earth in 1950.

Jones' career is full of great, even subtle performances in pictures like Since You Went Away (1944), Terminal Station and Beat the Devil (both 1953), which suggests that Vidor very much wanted her to writhe and glare and fling herself around the set as Pearl.

Because you have to understand that Vidor was a bridge between silent movies at their creative pinnacle and the studios' golden age, and Duel in the Sun is loaded with incredibly stylized scenes, from Pearl's arrival at Spanish Bit to those riders converging on the railway to Tiomkin's score, loaded to the gunwales with themes and motifs.

There are all those luridly coloured lights and matte paintings employed by the film's three cinematographers, few of which try to fool the viewer with realism as much as they place the film in a fever dream of the West. Vidor even reaches back to his German expressionist influences with scenes like the saloon meeting between Lewt and Sam Pierce (Charles Bickford), the ranch straw boss, a good man who's happy to make an honest woman out of the "fallen" Pearl.

The men stand on either end of an impossibly long bar, planted in pools of light, before Lewt beats Sam to his gun and makes himself a wanted murderer. His outlaw status inspires him to turn saboteur, derailing locomotives as they steam through his father's ranch, whistling "I've Been Working on the Railroad" to himself as he rides away from the mayhem.

But the most arresting moment is Laura Belle's death scene, telegraphed long before as Gish begins discretely coughing into her handkerchief. As Barrymore tearfully slumps in his wheelchair, recalling how he lost the use of his legs while jealously pursuing her and admitting his culpability in the evil character of their son, the camera follows Gish as she slowly rises from the bed.

She begins a haunting crawl, her eyes blank and sunken (Vidor had presided over a similarly incredible death scene by Gish in La Boheme), her movements eerie and unearthly as she makes a slow-motion lunge for her oblivious husband before slumping dead to the carpet. It's a stunning, kabuki-like performance, and it hints at what Vidor might have tried to achieve with the rest of his film even as it spiralled out of his control.

There's no other way to put it: this is a mad film, which somehow arrived in this condition despite the efforts of everyone who worked on it. They even felt moved to delete the happy ending from Busch's novel in favour of one where Jones and Peck arrive at the finale promised in the title, Pearl intent on killing Lewt before he can wreak any more death and havoc on his family and their ranch. They manage mutual destruction, but not before she painfully stumbles and drags herself over a hundred yards of rocky desert to die in his arms.

Both The Westerns From the Silents to the Seventies and Phil Hardy's The Encyclopedia of Western Movies insist that Duel in the Sun was not just the most commercially successful western ever made, but "one of the top grossing films of all time." It managed this while arriving in the theatres to mixed reviews and either heavily edited by local censors or without certification at all, though its massive budget and the $2 million Selznick spent on advertising on top of that meant that it barely broke even.

Gish and Jones both received Oscar nominations, though it was at the Venice Film Festival that Vidor and Selznick were celebrated, with the producer winning the Cinecittà Cup. Perhaps this explains why with the passage of years this morally delirious, more than faintly deranged departure from the classic westerns being made at the time ended up echoing in the surreal and highly stylized ones Italians would create over a decade later.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.