In Shakespeare's Richard III, the doomed young Prince, about to be sent to the Tower by Richard, his guardian, says that "Methinks the truth should live from age to age / As 'twere retailed to all posterity / Even to the general all-ending day." To which Richard, already planning his next move, mutters "So wise so young, they say, do never live long."

No one denies the value of truth, not even Shakespeare's villainous Richard, and even as we struggle to find it in a world flooded with information and opinion. I can't tell you where you'll find the truth in the news media despite being a journalist, but as a movie critic I do know that you'll find a lot of things in the movies – wit, spectacle, beauty, horror – but that factual, objective truth isn't among them.

At the start of director Stephen Frears' The Lost King (2022), we're told that the film – a drama based on amateur historian Philippa Langley's successful search for the grave of Richard III – is not just "Based on a true story" but that it's "Her story." This implication – that one person can own the truth – is a very contemporary idea, and one that undermines what is an otherwise entertaining picture.

When we first meet Langley, she's at work in Edinburgh at some dispiriting office that demands regular meetings, during which she learns that she's been passed over for a promotion in favour of several younger colleagues, including a pretty blonde whose brief time on the job has nonetheless caught the attention of her oafish boss, who tells Philippa (while apparently reading from a human resources manual) that "you are at the right level for you."

Sally Hawkins plays Langley as a beleaguered underdog; she suffers from myalgic encephalomyelitis (also known as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome), but more than that she's beset by oafish males – like her boss, and the father of one of her son's classmates who she meets when she takes the boy to a production of Shakespeare's Richard III.

A condescending, low-key bully, he mansplains the play to her when she remarks that she feels sympathy for the main character, asking her if she'll feel that way after he kills his nephews in the next act (which the man naps through). But when the actor playing Richard (Harry Lloyd, best known for his role in the first season of HBO's Game of Thrones) meets her eye when proclaiming to the audience that "I am determined to prove a villain," Langley succumbs to a fascination for the character, and begins researching his life story, certain that Shakespeare's compellingly evil hunchback usurper isn't the whole truth about the man.

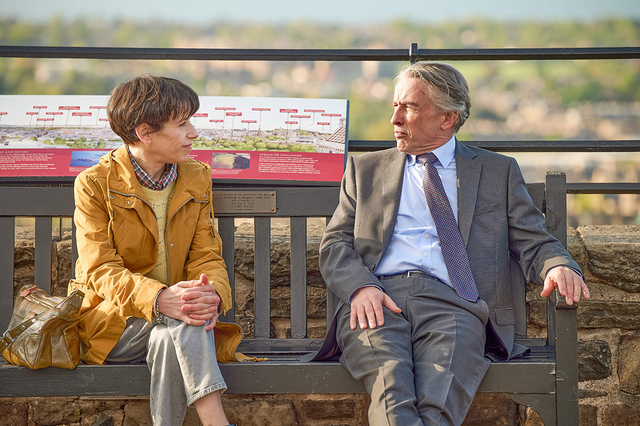

We see her flee the office during a dispiriting meeting about sales pitches, never to return. (Surely a fantasy for many.) She buys up all the books on Richard from a shop and spends her days researching him while neglecting to tell her teenage sons or her estranged husband John (Steve Coogan, who also co-wrote the script with Jeff Pope) of her obsession, which is deepened by the spectre of Richard III, who manifests in the form of the actor from the play as he gazes at her balefully.

Langley's obsession draws her to a meeting of the Scottish branch of the Richard III Society, held in the pub of the Albert Hotel in the shadow of the Forth Bridge. The society's mission is to rehabilitate the image of the king, which they insist has been distorted by propaganda disseminated by the Tudors who ended the Wars of the Roses when they defeated Richard at Bosworth Field, later parroted by Shakespeare in his play.

The society's Scottish members are a collection of eccentrics and misfits who feel ignored by both academic historians and a public who, if they think about Richard at all, are content to believe the conventional narrative of the murderous usurper. As amateurs and enthusiasts, they are held in contempt by academics and experts and considered not much different from conspiracy theorists by the general public, and both of them are happy to let Laurence Olivier's Richard III from his 1955 film sum up Richard for posterity.

Langley finds badly needed encouragement and camaraderie among them, joins their society on the spot and expresses a desire to pay her respects at Richard's tomb. That, they tell her, is a tall order, as no one knows where he was buried after he was carried off the battlefield at Bosworth, naked and slung over the back of a horse. If he's anywhere, he's likely somewhere in the city centre at Leicester, though they insist that the story of his bones being dug up years later and thrown in the River Soar by a jeering mob is a myth, long debunked.

Langley makes the pilgrimage to Leicester, to attend a lecture on Richard given by another oafish male – a Pooterish academic who pompously defers to the academic consensus about the king and cites the Royal Family website as an unassailable authority while mocking the Richard III Society, disparaging it as "the fan club."

The only kind face she finds there is John Ashdown-Hill (James Fleet), a historian and author who had just traced the DNA lineage of Richard's descendants, and who tells Langley that if she wants to find the king's grave, which was supposed to have been dug under the floor of the Greyfriars Church, she should look for whatever open areas remain in the city centre.

This leads to the most compelling part of Langley's story, but it's worth noting ahead of it all that not only had Langley left her job in marketing to write a screenplay about Richard before the start of the events in The Lost King, but that she had founded the Scottish branch of the Richard III Society, having been interested in the king since she was a teenager.

Richard's likely grave had been presumed for years to lie under one of three parking lots, and when Langley traveled to Leicester in 2004 to look for him, she claims she was overcome with a strong physical intuition while standing in the car park of a social services building, a feeling that persisted when she returned a year later and found that someone had painted the letter "R" (for Reserved) over the spot.

"My heart was pounding and my mouth was dry – it was a feeling of raw excitement tinged with fear," Langley recalled in The King's Grave: The Search for Richard III, the book she co-authored with historian Michael Jones. "As I got nearer the wall, I had to stop, I felt so odd. I had goose-bumps, so much that even in the sunshine I felt cold to my bones. And I knew in my innermost being that Richard's body lay here. Moreover I was certain that I was standing right on top of his grave."

It was only after this that Langley contacted Ashdown-Hill, who had traced Richard's line from his sister down to a retired journalist living in Canada and her son, a carpenter with a workshop in Camden. She enlisted the historian in a team organized by the Society to fundraise a search for the king's grave, which obtained the assistance of Leicester city council, the University of Leicester and archaeologist Richard Buckley and began three weeks of excavations in the social services car park in 2012.

I have been obsessed with archaeology since I was a boy, and my interest managed to survive the moment when I realized that working an archaeological dig was less likely to involve uncovering the tomb of a pharaoh than excavating ash heaps, trash middens, spoil dumps and abandoned privies. So I was fascinated when news of Langley's successful search for Richard's grave broke internationally, with the remarkable story of how they had found the king's bones on the first day, in the first trench, dug over the spot where that "R" had been painted.

It sounded too good to be true, though it seems that it's one of the few plot points in The Lost King that is closest to the truth.

Langley's journey in the film is one beset with obstacles embodied in a series of oafish males. Worst of all is another Richard – Richard Taylor (Lee Ingleby), a bureaucrat from the University who initially scoffs at Langley when she presents her appeal for support for the dig in Leicester. She's rescued from his skeptical opposition by Sheila Lock (Amanda Abbington), chair of the city council, who gives her the good news about being fully funded along with advice to avoid talking about her "feelings", which only alienates men like Taylor.

She's also dismissed by Richard Buckley (Mark Addy), who is slightly kinder while he intends to ignore her appeal for him to lead the dig – a decision that he only reverses after the university cuts his funding, forcing him to be less discriminating with his clients. Even her soon-but-not-quite-ex-husband gaslights her when he discovers how she's been spending her time, though Coogan still manages to give himself some of the best lines in the picture.

The only really kind male presence in Philippa's life is the ghost of the king, who teases her with his silence until she asks him why he pretended to fall from the bridge over the River Soar, to which he replies that he thought it would be funny. In the context of her slightly unusual and definitely depressing domestic situation (her husband walked out on her, though he claims it was "a constructive dismissal", but he moves back in to sleep on the couch when leaving her job strains their finances) Lloyd's Richard – handsome and attentive in a way that no other man in the film is – is a romantic spectre like Rex Harrison's sea captain in The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, emotional support for the lonely and discouraged Langley.

"I feel like I've been cuckolded by a ghost," John tells her, though he ultimately rallies behind his wife, even anonymously gifting money to the Society's crowdfunding campaign that he had intended to spend on a car.

Even after finding Richard's leg bones in the first trench, Buckley and his team dismiss the find as just some friar's grave and concentrate instead on finding the remains of Greyfriars Church; Langley is driven to despair by their indifference to her, the client, until John encourages her to demand that Buckley respect her intuition, which leads to the eureka moment when the dig's osteologist Jo Appleby (Phoebe Price) and supervisor Matthew Morris (Alasdair Hankinson) find themselves gazing down on the skeleton of a man with severe curvature of the spine.

This brings the University and Taylor back to the site, where they take credit for the discovery and commandeer the media frenzy that descends on Leicester. "We're playing catch-up now," he tells Buckley conspiratorially. "Things are changing rapidly." Banners are quickly printed by the University reading "WE FOUND RICHARD" and Langley finds herself sidelined at the press conference announcing Richard's rediscovery, after which Taylor mutters to her that he has to deal with approving Richard souvenirs – "chocolates and shot glasses, that sort of thing" – in what sounds like a humble-brag.

The University even hoards Richard's bones, taking advantage of an oversight in paperwork made by Buckley to negate Philippa's pledge to treat the king's remains with dignity and ensure their reburial in a place of honour in Leicester Cathedral. In real life, this led to a lawsuit between the University and the Plantagenet Alliance, a coalition of the king's descendants who wanted Richard to be buried in York, not Leicester.

Worst of all, Buckley's support has apparently been bought with a permanent job and an honorary degree, though he, along with Appleby and Morris, have the good grace to look faintly ashamed by their betrayal of Langley. A university is "not a benevolent seat of learning," he tells Philippa. "It's a business."

We are primed to find this kind of story compelling; of underdogs and inspired amateurs pitted against a system that denies and stifles until it's forced to steal credit and shift the narrative to cover the traces of its intransigence. Ignored at the press conference, Philippa is also sidelined at the black-tie gala celebrating the dig's success, though she snatches victory from defeat when she opts instead (at Buckley's covert urging) to address the students at a girls' school.

It's a great story, but you don't find much of it in the account Langley tells in her book, or in either of the two documentaries filmed with Langley's cooperation during and after the dig. There were, in fact, as many as three film crews on site during the dig, though you only ever see one TV crew in the movie, after Richard's bones are uncovered.

A Channel 4 program, Richard III: The King in the Car Park, followed Langley during and after the dig, though the sharpest moment of conflict isn't while the king's bones are ignored in favour of other archaeology, or at the press conference, but when Langley wants to drape the cardboard box containing Richard's remains with a replica of his standard when they're being removed from the dig site.

She has an obvious emotional attachment to the earthly remains of a man who she feels has been maligned unfairly by history; in line with the Society's mission statement, she believes he was never a usurper, tyrant or murderer, and that he wasn't even a hunchback, so the reveal of the skeleton's severe scoliosis is a moment of obvious dismay for Langley. In Coogan and Frears' film, her sympathy for the king is inspired by feeling judged unfairly for a disability, of suffering from malicious gossip you are unable to respond to or deny.

But osteologist Jo Appleby, who painstakingly dug Richard's bones from the ground (after accidentally putting a hole in his skull while clearing earth with her mattock; we don't see this in The Lost King), wants to retain her professional objectivity and vocally disagrees with Philippa's desire to cover the remains with a royal standard, telling her that they still have no proof that it's really him yet, and that she won't take part in this ceremony. Ashdown-Hill (who died in 2018) ends up placing the flag-draped box in the back of the white van that will take it away for testing and study.

The documentary also shows Langley on the podium at the press conference, while Taylor makes only a fleeting appearance. Neither the Channel 4 film nor the book show Richard Buckley as the impatient, even truculent man we see in The Lost King. In her book Langley writes that she was "thrilled that Richard Buckley was asked to declare the identity of the remains," and while recalling the jovial mood shared by the team at the dig, she describes Buckley as "this big bear of a man with such a big heart, and thank God that he agreed to come with me on this car park adventure."

Life, we're told, is rarely sufficiently dramatic for the purposes of art, so it needs some help – some judicious editing and adjustments to focus. And audiences are clearly ready to respond to narratives about power and underdogs that they recognize easily. Two years ago Netflix released The Dig, a film about the discovery of a treasure-filled burial at Sutton Hoo in the early months of World War Two, starring Carey Mulligan as Edith Pretty, the upper class widow who hired Basil Brown (Ralph Fiennes), a veteran amateur excavator, to dig one of the mounds on her property.

After being ignored by the fusty archeological establishment, they descend on the site when not just the remains of a ship but Anglo-Saxon gold is uncovered, sidelining Brown and demanding the treasure and the credit go to the British Museum. There's a feint at a romance between Pretty and Brown, but the drama really coalesces in the conflict between the entitled and opportunistic academic toffs and Pretty, a woman, and Brown, a working-class man.

Something obviously went very wrong between the discovery of Richard's remains in that car park and his reburial in Leicester Cathedral in 2015. (His funeral pageant is the climax of The Lost King, with the real Langley seen in a cameo, while Hawkins' Langley and Fleet's Ashdown-Hill notice the pompous lecturer from early in the film at a prominent place by the coffin, musing if he's "joined the club.")

When The Lost King was released last year it sparked a feud between the filmmakers (Langley was a producer on the picture) and Leicester University, who claimed that they had been cast as the story's villains. Matthew Morris told the Guardian that "It was always going to be Philippa's story, but my big concern is how we are shown. It is unfair if it doesn't show our partnership with her."

Richard Taylor, now at Loughborough University, said that "Tension makes a good story but it doesn't necessarily make it true. If you are going to portray real people, at least involve them. It strikes me as pretty reckless." He told the BBC in October of last year that he was "shell-shocked," and that legal action was "likely".

The Lost King ends with Langley's triumph: Richard is buried at the centre of Leicester Cathedral with his coat of arms on his tomb, and the Royal Family amends their website to describe him as an anointed king, not a usurper. Philippa Langley was awarded at MBE along with John Ashdown-Hill at the Queen's 2015 Birthday Honours. (Richard Buckley, however, received the OBE, an upgrade.)

A museum and visitor's centre was built by the city of Leicester over the site of Richard's grave in the car park, the hole still open as Langley and her team left it. No one can say, at the remove of centuries, if Richard was either a good king or a tyrant, and it's doubtful that he'll ever be truly clear of guilt in whatever fate befell the Princes in the Tower. But the image of Philippa Langley standing over the letter "R" painted on the asphalt of the car park will probably always be the better story of how he was found again, whatever the truth might be.