My grandfather, who was born when Charles Dickens was still alive and writing, left me his books, including copies of David Copperfield, Bleak House and Barnaby Rudge, which is good because at no point in either grade school or high school did Dickens appear on any reading list. Dickens was – and still is – one of the most famous novelists ever, but like Mark Twain and Tolstoy, I have no sense whatever that he's being read.

Back at the end of World War Two, when David Lean was a young director presented with Dickens' Great Expectations as his next project, he had only read A Christmas Carol, which remains the sole work by the writer that's probably still read – mostly because it's short and concise and sums up nearly everything we think we need to know about Dickens.

Indeed, the adjective "Dickensian" and a handful of scenes (Oliver Twist asking for more gruel, Scrooge confronted by Marley's ghost) are the whole of our understanding of Dickens today, and comprise much of our image of the inequities of Queen Victoria's England as it persists in popular imagination. Much the way that Jane Austen is the foundation, walls and roof of what we know about class and the status of women in Georgian Britain – though I suspect that Austen is more read than Dickens.

I thought Great Expectations was a horror movie when I saw it for the first time, split into four parts and aired over the course of a week on Elwy Yost's Magic Shadows back in the '70s. (I've written about Yost before; everybody deserved someone like Uncle Elwy back in the age of over-the-airwaves broadcast television.) Part of that was how well Lean evoked the powerlessness and fear that was the worst part of childhood.

It's easy to remember when we first see young Phillip "Pip" Pirrip (Anthony Wager) as he makes his way through the fog-shrouded landscape of Kent's coastal marshes, walking a narrow path between the water, past dangling nooses on empty gibbets. He's clearing the weeds from his parents' grave in a churchyard where the trees look poised to lunge at him when he runs straight into Magwitch (Finlay Currie), a convict escaped from the prison hulks who threatens to cut out his liver.

Young Pip is given a stark choice – incur the wrath of his shrewish sister Mrs. Joe (Freda Jackson) or steal food and drink and a file for Magwitch. He's bracing for the consequences of the theft when soldiers arrive, sweeping the marshes for not one but two escaped convicts. Pip and his kindly brother-in-law Joe the blacksmith (Bernard Miles) watch as they're both captured while fighting each other on a tidal mud flat, but Magwitch surprises the boy by taking sole blame for the stolen food.

Not long after the boy is volunteered by Uncle Pumblechook (Hay Petrie), a pompous and socially ambitious relation, to spend a day a week at the home of Miss Havisham (Martita Hunt), the rich madwoman at the apex of local society. She's a recluse who has frozen time at the moment when she was jilted at the altar, living in the cobwebbed ruin of her wedding party, complete with rat-infested "bride cake". She has an adopted ward, the pretty but cruel Estella (Jean Simmons), who torments Pip while they play cards, to the apparent amusement of the old woman.

By this point in the film there's nothing that won't convince a young person primed for Dickens with Scrooge and his ghosts that they're watching a gothic horror story, and you brace for whatever dark fate is in store for young Pip.

One of the great ironies of Dickens as a force for social reform in Victorian society is that he largely neglected the children of his first marriage. (David Lean would also neglect his son by his own first marriage over the course of his five subsequent ones.) It's a measure of how unsentimentally childhood was regarded in the 19th century that someone like Dickens was famous as a powerful voice for the children of the poor, who were treated as little more than chattel or cheap labour.

In an early chapter of Great Expectations Dickens has Pip tell us that his "sister's bringing up had made me sensitive. In the little world in which children have their existence whosoever brings them up, there is nothing so finely perceived and so finely felt, as injustice..."

"Within myself, I had sustained, from my babyhood, a perpetual conflict with injustice. I had known, from the time when I could speak, that my sister, in her capricious and violent coercion, was unjust to me. I had cherished a profound conviction that her bringing me up by hand, gave her no right to bring me up by jerks. Through all my punishments, disgraces, fasts and vigils, and other penitential performances, I had nursed this assurance; and to my communing so much with it, in a solitary and unprotected way, I in great part refer the fact that I was morally timid and very sensitive."

Kevin Brownlow in his book David Lean: A Biography reminds us why the director had such a towering reputation for technical mastery in the service of visual storytelling. Working with production designer John Bryan he created dense tableaux that seem to overwhelm young Pip using forced perspective and custom-made furniture.

Bob Huke, camera operator on the film, recalled to Brownlow that "he said, for instance, when we shot the children, we would use 35mm lenses, and 24mm, which was the widest lens in those days. Even on close-ups we'd use the 35mm, so the set around them would seem so much bigger. But when we shot them when they're grown-ups, we'd use longer lenses. 50mm and 75mm. So it was exactly the same set, but it was a vast, cavernous shadowy place when they were kids, and it was a dreary, dirty, run-down house when they were adults."

Lean had been cajoled into attending a 1939 stage adaptation of Great Expectations by his second wife, Kay Walsh, a writer and actress who had shared a studio dressing room with Martita Hunt. It had been adapted by a young actor named Alec Guinness and starred him as both narrator and Herbert Pocket with Hunt as Miss Havisham.

The director wasn't a Dickens fan, but he had remembered the play and suggested it to his producer Ronald Neame after the success of Brief Encounter. An early attempt at digesting Dickens' novel into a script by novelist and playwright Clemence Dane was a disaster, so Lean and Neame and writer/producer Anthony Havelock-Allan had a go at it, with contributions from Cecil McGivern, later head of drama at the BBC, and Lean's wife Kay Walsh.

Lean knew what so many would learn – that a faithful cinematic adaptation of Dickens would be leaden or lugubrious, or both. "Lots of people have come a cropper on this," Lean told Brownlow, "and I think Ealing Studios came a cropper on Nicholas Nickleby. They had every scene in the book in snippet form in the film. It just does not work. You have to cut and give it weight and do it proud. You have to savour Dickens, you have to enjoy him. You can't just skip through in shorthand."

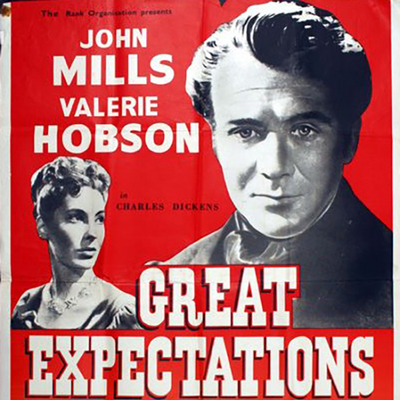

What Lean had for his film adaptation was Martita Hunt as Miss Havisham, who created a suitably intimidating, unapproachable presence on set with designer John Bryan, and Alec Guinness as Pocket, the two actors already intimate with their roles. John Mills, who had worked with Lean on In Which We Serve and This Happy Breed, played the adult Pip, and the lovely Valerie Hobson was cast as the adult Estella.

Hobson would recall later that she felt ignored by Lean on set, who only required the actress to convey her character's heartlessness. "I thought I very nearly disappeared altogether," Hobson told Brownlow. "Let's face it, I don't think Estella is a good part. It's very thinly written and it's only as good as you can fill it out. And I wasn't allowed to fill it out even with what talents I might have had."

Hobson was right, but it didn't seem to matter much in the latter part of the picture, after Pip has grown up and comes into the good fortune of an anonymous benefactor who has given him a living and the means to move to London and become a gentleman. He takes his leave of Joe, to whom he had been apprenticed, and rides the coach through Dartford, Woolwich and Greenwich to the city, where his life is under the nominal and indifferent supervision of Jaggers, a lawyer with offices between St. Paul's and Smithfield Market.

Jaggers is played by Frances L. Sullivan, who had the role in a 1934 Universal production of Great Expectations with Jane Wyatt as Estella, and would play an indelible version of Mr. Bumble in Lean's next film, Oliver Twist. Last seen in this column in Jules Dassin's Night and the City, Sullivan was one of those great character actors who improve any film regardless of the quality, though he had a peculiar facility with judges and barristers.

Having glimpsed Jaggers once as a child on the stairway at Miss Havisham's, Pip assumes that the old woman is his benefactor, and that she wishes him to court and marry Estella, now returned from being educated in France to debut in London society. It's a reasonable hunch, as he discovers that his flatmate in the city is Herbert Pocket, last glimpsed as an annoying young boy obsessed with pugilism, who Pip had easily thrashed in Miss Havisham's dusty garden.

Pip's great good fortune is contrasted with the other half of the world he sees at Jaggers' office, where the lawyer's apartments overlook Newgate Prison. Among the macabre trophies in Jaggers' office is a framed noose, and the death masks of several of the lawyer's most notable clients, cast moments after they were cut down.

In Dickens' novel Pip narrates a wander through the streets adjacent to Jaggers' offices, which takes him past Newgate to the Old Bailey, where trials are in session. Here "an exceedingly dirty and partially drunk minister of justice" offers him a front seat in court for half-a-crown to watch the judgments handed down.

"As I declined the proposal on the plea of an appointment, he was so good as to take me into a yard and show me where the gallows was kept, and also where people were publicly whipped, and then he showed me the Debtors' Door, out of which culprits came to be hanged: heightened the interest of that dreadful portal by giving me to understand that 'four on 'em' would come out at that door the day after to-morrow at eight in the morning, to be killed in a row. This was horrible, and gave me a sickening idea of London: the more so as the Lord Chief Justice's proprietor wore (from his hat down to his boots and up again to his pocket-handkerchief inclusive) mildewed clothes, which had evidently not belonged to him originally, and which, I took into my head, he had bought cheap of the executioner. Under these circumstances I thought myself well rid of him for a shilling."

Lean is more explicit, having Mills' Pip look out of Jaggers' window at the lawyer's bland urging to watch the gallows in action in front of a roaring crowd. Why all this is germane to the story of a young man suddenly blessed with the means of a living becomes clear when Pip discovers, late one stormy night, that his benefactor isn't Miss Havisham but the convict Magwitch.

Transported from the prison hulks to forced labour in the antipodes, Magwitch had earned his freedom and riches in sheep and livestock. His fortune was put to the service of the only person he could remember being kind to him, and administered through Jaggers, who has a lawyer's supreme moral indifference to the nature and intentions of his clientele.

He could not, though, resist the temptation to return to England and reveal himself to Pip – doubly dangerous as he's not just risking arrest and the gallows but the wrath of his nemesis, the convict he had been wrestling on the mud flats when he was captured. (In Dickens' novel, this convict is Compeyson, the conman who had jilted Miss Havisham, but Lean and his scriptwriters were content to leave this out, as the revelation that Estella is actually Magwitch's lost infant daughter was very nearly one melodramatic improbability too far.)

At no point, in either the book or the film, do we know what Magwitch has done to justify such brutal treatment by the law. What Dickens' readers – and perhaps even an appreciable minority of viewers watching Lean's film in 1946 – would know was that the British legal system in the 19th century was full of draconian punishments for what seem today like minor crimes, in which prison hulks and transportation were considered innovative mercies.

In The Fatal Shore, his masterful history of Australia, the art critic Robert Hughes makes the point that, as harsh as the British legal system was at the end of the 18th century, it was still considered liberal and lenient compared to those on the continent, based on Roman and Canon law, whose practitioners were astounded that a suspect in England "could not be tortured until he confessed, he could not be held indefinitely without bail or trial, and he was innocent until proven guilty."

The impression that they were soft on criminals, Hughes writes, inspired in Britain "the draconic laws they created to avenge their sense of a disturbed social order...If detection and arrest were feeble and trials tenderly fair, what punishment could keep men from crime? Only the extreme one: hanging without the benefit of clergy."

"During the reigns of the first three Georges, law enacted death upon what seemed a limitless variety of human deeds, from infanticide to 'impersonating an Egyptian' (posing as a gypsy). Between the enthronement of Charles II in 1660 and the middle of George IV's reign in 1819, 187 new capital statutes became law – nearly six times as many as had been enacted in the previous three hundred years. Nearly all were drafted to protect property rather than human life; attempted murder was classed only as a 'misdemeanor' until 1803. These grapeshot laws scattered death impartially. Why must forgers hang? Because the increase of paper transactions in eighteenth-century banking and business – checks, notes, bonds shares, as distinct from concrete transfers of bags of gold – had made property of all sorts more vulnerable to forgery? Why was it death to 'steal an heiress'? Because like a queen bee swollen with jelly, an heiress was property incarnate; her abductor went to the gallows not for rape but for his theft of a family's accumulated goods and rights."

It was the legacy of capital punishment that lined the Kent marshes of Pip's childhood with gibbets and made Newgate's mass hangings public spectacle. But the injustice of it all didn't go unnoticed, even among the barristers who fought for convictions and the judges who handed them down.

Authorities kept back as many as they could from the gallows, but prisons overflowed and the hulks anchored in the Thames Estuary multiplied. After America rebelled the colonies became unavailable to exile criminals, though just in time a new British possession – "a useless continent at the rim of the world" as Hughes calls it – became available.

"From there, the convicts would never return," he writes. "The names of Newgate and Tyburn, arch-symbols of the vengeance of property, were now joined by a third: Botany Bay."

Pip's frustrated love for cruel Estella has nowhere near the drama of Pip and Pocket conspiring with Jaggers' assistance to smuggle Magwitch out of England – a plan that nearly succeeds but for Compeyson's vengeful and ultimately fatal connivance, which leads to Magwitch sentenced to the gallows at the Old Bailey.

Anyone who's read Dickens' novel knows that its ending is far more melancholy than the one in Lean's film. While Lean was busy finishing Brief Encounter, Neame and the other writers wrestled unsuccessfully with an ending, until the director's wife Kay found a solution.

"I thought if Pip had a long white beard," she told Brownlow, "and Estella had put on forty pounds and they met in a graveyard, Wardour Street wouldn't come through with the money and anyway, you couldn't finish the film like that. And so I got the idea of Miss Havisham and her influence on Estella, who'd just been jilted. It seems so obvious now that she would repeat the pattern of Miss Havisham. What was really good was Pip coming back and the voices – 'Don't loiter, boy!' and the gate creaking and the camera going up the stairs and you think you're going in to Miss Havisham and it's not her at all, it's Valerie as Estella."

They had already given Martita Hunt a spectacular death scene – her screams as her wedding dress catches fire are as terrifying as Pip's meeting with Magwitch at the start of the picture – and Kay Walsh made John Mills "absolutely thrilled" with his heroic scenes at the climax of the picture, before the romantic escape from Miss Havisham's ruin that's as dramatically satisfying as it departs utterly from Dickens.

Walsh didn't receive much of a reward for her contribution to the picture; Lean, a compulsive philanderer, began an affair with costume designer Maggie Furse on location, leaving his wife to move in with Furse while they were still filming, and ending the affair not long after it was finished. Three years later Lean would marry his third wife, actress Ann Todd.

The budget came to nearly £400,000 – more than the Technicolor films being made at the same time – but opened to rave reviews and great box office on both sides of the Atlantic. During post-production Lean had flown to America to quietly take the measure of American audiences, riding the subway to watch films in Brooklyn and the Bronx. In a decade he'd be making far fewer films, though each one would land in the theatres like an avalanche. But before then he had to make one more Dickens film that become a substitute for actually reading Dickens.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.