There should be a lot more movies about Wall Street, the money markets and American capitalism if you consider its importance to the west in general and America in particular. But going back to the 1929 crash, there were remarkably few pictures about this cataclysmic event; The Crash, a 1932 pre-code picture starring Ruth Chatterton and George Brent, is one of the few where the plot explicitly deals with it, though there were certainly plenty of dramas, comedies and musicals in the '30s where fortunes lost and savings wiped out in a single day affect character or plot, though the crash is usually described as an act of God more than an unlucky collision of economic policy and social mania.

Wall Street, the 1929 Crash and volatile markets play a part in films as different as Dance, Fools, Dance, Citizen Kane, Edison, the Man, Kentucky, The Great Ziegfeld, It's A Wonderful Life, Auntie Mame, The Helen Morgan Story and The Solid Gold Cadillac, and the financier and portly plutocrat were stock characters in countless screwball comedies. Hollywood seemed to lose interest in the markets during the counterculture tsunami of the '60s (no surprise) though they would re-appear gradually with the following decade, most notably in Ned Beatty's showstopping "The World is a Corporation" speech in Network.

The markets would return as a setting and a subject again in the '80s, starting with films like Rollover, Trading Places, Prime Risk, Working Girl, The Bonfire of the Vanities and especially Wall Street. Since then the bond trader, money manager, stock analyst, ambitious CEO and financial wizard have re-emerged with a vengeance in Rogue Trader, Boiler Room, American Psycho, Matchstick Men, Arbitrage, The Family Man, Company Men, Joy, Cosmopolis, Gold, Money Monster, Limitless, Equity, The Founder, The Informant!, The Panama Papers and The Banker. As a covert genre, it may have finally reached its full maturity in recent pictures like Margin Call, The Wolf of Wall Street and The Big Short.

It's not hard to explain why: while meltdowns in the markets happened once in a generation or two, they've become relentlessly cyclical – bubbles occurring roughly every decade, with each new one anticipated just as we've dug ourselves out of the wreckage of the last. And while you might presume that we've become more familiar with the workings of the market by now, the increasing complexity of each new collapse (the bond markets of the '80s versus the "financial instruments" of the subprime credit crisis of the 2000s) means that every film contains at least expository lesson for viewers. (Though few were as amusing as Margot Robbie explaining subprime mortgage bonds in a bubble bath in The Big Short.)

(An aside: I spent the '80s boom in the nosebleeds, a financial illiterate watching all this happen without understanding any of it; all I knew was within a few months of Black Monday half the magazines I wrote or shot for were out of business. Twenty years later I'd be out of work when the newspaper I worked for laid off all its writers, citing the economic uncertainty caused by the subprime crash south of the border – though not the dismal business model of a print newspaper chain. It's like living in a country with conscription but no right to vote.)

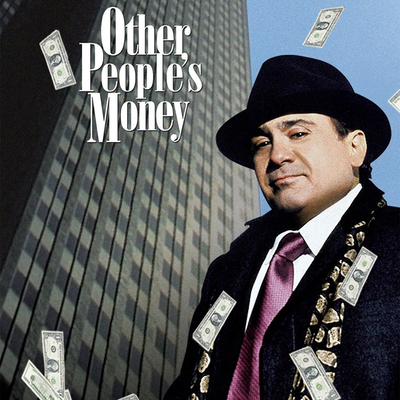

Other People's Money (1991) gets lost in this list of films, probably because it sits deep in the shadow of Oliver Stone's decade-defining Wall Street (1987), and because it seemed far less crucial when it came out four years after Black Monday. It's a gentler, more circumspect film about the people who work and live in the markets, based on a 1989 off-Broadway play by Jerry Sterner, who left his successful real estate business for a life in the theatre.

The film begins with its protagonist/antagonist Larry "the Liquidator" Garfield (Danny De Vito) breaking the fourth wall and addressing the audience as he will throughout the film, telling us that he loves money, "more than the things it can buy." Larry is a corporate raider with a glass-walled corner office at Broad and Wall Streets, and his acquisitive eye has been caught by New England Wire & Cable, a small but profitable business in Rhode Island.

The camera cuts from the Financial District to Rhode Island, where the employees of New England Wire & Cable assemble for a pre-Thanksgiving "family photo" with the company president Andrew "Jorgy" Jorgenson (Gregory Peck). The business, we soon learn, is 81 years old, and Jorgy has been in charge for twenty-six of those years, but its gabled and cupola'd red brick factory looks much older, positively Victorian, and the antique setting is underscored by a photographer taking the company picture not with a Hasselblad or a Mamiya RZ67 but an old wood-and-brass view camera.

(I'm sorry, but as a photographer I can't help but notice these things.)

Larry's interest in the company hasn't gone unnoticed. Jorgy's wife Bea (Piper Laurie) and the company's manager Bill (Dean Jones) both warn him about sudden activity in their stock, but he ignores them right up until Larry shows up at their gates in his stretch limo to make what he considers a friendly offer.

Looking over the sparks and flames of the shop floor, he says that they have $120 million in equipment that's worth at least $30 million in salvage value. The film's production designers do a good job making New England Wire & Cable look venerable and historical; the factory scenes were shot at two mills in Connecticut, both of which were out of business by the end of the decade. The result is that Larry's estimation of the machinery's value seems generous – it looks more like an industrial museum in some slowly-reviving town in the rust belt.

The company also owns land, and a few other businesses that Jorgy bought while things were booming, and they're making the profits that are keeping the money-losing wire and cable factory open. Best of all, they have no debt, which is what has brought Larry all the way to Rhode Island with an offer to buy the company – an offer that Jorgy turns down angrily, knowing that the first thing Larry will do is shut down the factory and put everyone out of work before selling off the valuable leftovers.

Larry is surprised at Jorgy's intransigence, and has his people file a 13(d) with the Securities and Exchange Commission as soon as he leaves, signalling the start of a stock takeover. Bea and Bill inform Jorgy that the company's lawyers on retainer aren't up for the battle that Larry is going to bring, and convince him to hire Bea's daughter Kate (Penelope Ann Miller), a big deal New York corporate lawyer, to defend them from the imminent hostile takeover.

Hostile takeovers, leveraged buyouts, asset stripping and "corporate raiders" were a major part of the Wall Street boom of the '80s, embodied in characters like Ron Perelman, Carl Icahn and T. Boone Pickens. (Richard Gere's Edward in Pretty Woman (1990) was a corporate raider, as was Wall Street's Gordon Gekko.)

Mergers & acquisitions departments had been fixtures at banks for a century, but deregulation and changes in investment law at the dawn of the decade had joined them hand in hand with the booming bond market to create an insatiable corporate appetite for underperforming or undervalued companies whose component parts could be bought and sold for growth or profit (or preferably both. Either was good for the lawyers who stood to make money off takeover battles no matter how they went.)

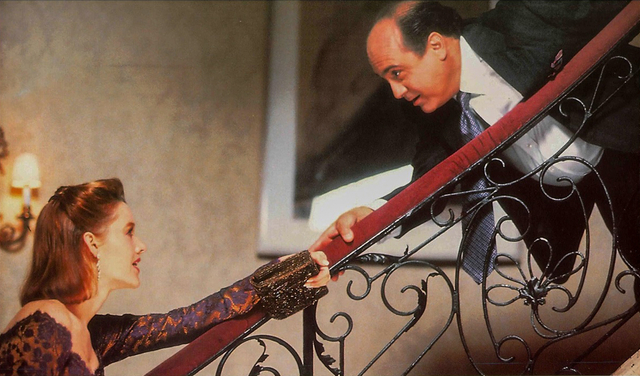

Penelope Ann Miller was the Hollywood beauty of 1991, just after Julia Roberts and Demi Moore, and just before Winona Ryder and Bridget Fonda. It's a role agents ache to bestow on their clients, though it often does little more than demarcate the peak of their career – a poisoned chalice in retrospect. Her Kate has brains and looks, though we're meant to appreciate the latter first, in a shot from Larry's perspective where he pans up from her pumps to her red hair after she walks into his office.

The film's trailer suggests that director Norman Jewison (or the producers) cut several shots that lingered on Miller's attributes before the film was released. This seems appropriate to Jewison's reputation as a solid but generally style-free director of politely liberal sensibilities (In the Heat of the Night, Fiddler on the Roof, Moonstruck) who tended to avoid the salacious in favour of the sentimental.

This means that the film that follows is a love story sublimated into the hostile takeover Larry the Liquidator attempts against New England Wire & Cable. There is, to be sure, something unappetizing about the prospect of a romance between the comely Kate and the troll-like Larry. You can't help but wonder how different the movie would have been if, say, Richard Gere had been cast instead of De Vito.

Even when they roamed Wall Street at the zenith of their power – the "masters of the universe" defined and diminished by Tom Wolfe in Bonfire of the Vanities – the corporate raiders and junk bond titans of the '80s were rarely seen as heroic or even attractive. (Michael Douglas' Gordon Gekko did a lot to buff up their image even in a film that celebrated their imminent downfall.)

In A Giant Cow-Tipping by Savages, probably the definitive history of the M&A era, John Weir Close describes Canadian real estate tycoon and corporate raider Robert Campeau as a hopeless neurotic, "a frightened man, prone to sudden and rather cringe-inducing admissions of doubt ...vain ... should have been in treatment." Carl Icahn is described by an associate as "like a smart person playing a slightly psychotic person."

British financier Jimmy Goldsmith is a virtual bigamist, a hypochondriac with an obsessive-compulsive streak and a horror of rubber bands; his third wife recalls that "he could be physically sick if he saw one." Media baron John Kluge and his wife build a baronial estate in rural Virginia and hire an Irish baronet as gamekeeper to oversee their lavish shoots; while collecting an award from a conservation organization, their titled gamekeeper and his staff are on trial for the slaughter of endangered raptors and local wildlife and at least a dozen of their neighbours' dogs that are found buried in mass pits on their property.

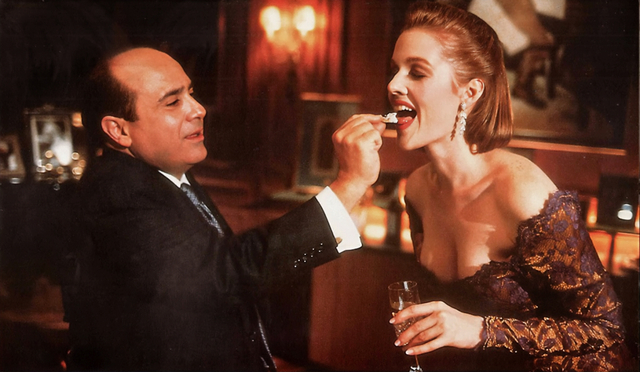

De Vito's Larry seems a lot more benign by comparison. Bronx-born, he leads with his vulgar manners and low tastes, celebrating Dunkin' Donuts and the "winner takes all" ethos of capitalism. Meeting Kate for lunch at a traditional sushi restaurant with private rooms, low tables and a geisha waitress (remember when sushi wasn't fast food with "all you can eat" menus?), he asks for a knife and fork and bread. But when Kate leaves early, he picks up his chopsticks and begins chatting with their waitress in Japanese.

Larry, we learn early on, is lonely. Until Kate enters his life, the only female he seems to interact with regularly is his secretary (Mo Gaffney) and Carmen, the proprietary stock ticker terminal at his bedside. (Like so many films of the era, computer interfaces are far more graphic and readable here than their real-life counterparts.)

In his lavish but empty townhouse, Kate finds a picture of the one that got away – a high school crush who rejected him for a jock – alongside a signed photo of violinist Isaac Stern. Larry plays the violin (badly) and has a passion for opera. He propositions Kate crudely (he challenges her to have sex with him; whoever comes first has to concede the battle for New England Wire & Cable) but is genuinely hurt when he realizes that winning his hostile takeover bid means losing any chance he imagined he had with her.

The masters of the universe and "big swinging dicks" of the trading floors were easy to hate, especially when the bubble that created them finally burst. In Liar's Poker, the bestselling memoir of his time at the (ultimately doomed) investment bank Salomon Brothers, Michael Lewis (author of the book that inspired The Big Short) reflects on how and why firms like his encouraged the worst excesses of behaviour from their (mostly male) employees.

"They sensed that they needed to shed whatever refinements of personality and intellect they had brought with them to Salomon Brothers. They were the victims of the myth, especially popular at Salomon Brothers, that a trader is a savage, and a great trader is a great savage. This wasn't exactly correct. The trading floor held evidence to that effect. But it also held evidence to the contrary. People believed whatever they wanted to believe."

The whole idea of Larry and Kate would be absurd if Jewison didn't invest so much energy into farming as much chemistry as possible out of their scenes together, and if Kate's strategy with Larry wasn't built on a relentless tease. Itemizing his reasons for joining battle with her in their first meeting, her last and most persuasive point is that, if he doesn't, "I won't love you anymore."

At first Kate's tactics seem like a reasonable card to play with a man who's otherwise motivated by simple profit and loss, but when her teasing reveals his vulnerabilities Jewison gives them an actually romantic scene, in bed but separated by a phone line (like Doris Day and Rock Hudson in Pillow Talk), where he charms her with his awful fiddling – an earned intimacy that he realizes all too soon can't go anywhere if he wins the proxy battle by shareholder votes that she dares him to join.

In the meantime her mother has snuck into Manhattan to offer him "greenmail" – a million dollars of her own money if he'll go away. (Both Larry and Jordy agree that greenmail is "immoral".) In another secret meeting Jordy's right hand man Bill, tired of waiting to have his loyalty to the company rewarded and bitter at how everyone else seems to be "looking out for themselves," sells his proxy vote to Larry in exchange for a million dollars – if those shares turn out to have been key to Larry's winning bid.

The film's climax comes at the shareholder's meeting, where Jordy makes a speech pleading to invest in the value of a business to its employees and community despite the balance sheet. Keep in mind this is delivered by Gregory Peck – the voice of Philip Green, Tom Rath and Atticus Finch. The performance (Peck's last major one) comes front-loaded with a moral authority that would have been undeniable even if New England Cable & Wire hadn't been assiduously painted in the warmest of hues as the embodiment of American industry at its historic apex.

Larry's speech, on the other hand, is hard to hear as anything but a reprise of Gordon Gekko's "Greed is Good". He says that the community could have offered the company tax breaks if they wanted it to survive a downturn, and the employees could have taken lower wages if they valued their jobs. He points out that new technology like fibre optics is making wire cables obsolete, and invokes the metaphor of the last buggy whip manufacturer during the rise of the automobile.

It's as unsentimental as it is true, and like most of these takeover battles in the real world Larry wins and the plant is closed. (One of the rare exceptions from the M&A boom was Gordon White and James Hanson's failed takeover of Cummins Engine, the diesel manufacturer that made Columbus, Indiana its virtual fiefdom, the subject of a great chapter in John Weir Close's book.)

What makes Other People's Money such a period piece – besides the boxy double-breasted suits on the men and Penelope Ann Miller's miniskirts and padded shoulders – is the Japanese. Early in the film, arranging for a place to meet Larry for lunch, Kate asks her staff if the Japanese celebrate Christmas.

"No, but I hear they're buying it," jokes one of her associates.

At their sushi lunch Larry muses about how the Japanese rebounded from being bombed flat during the war, rebuilt their economy and became so important that he has his staff learning Japanese. During the shareholder's meeting we see Kate quietly confer with a trio of Japanese businessmen, who turn out to represent an auto parts conglomerate who need someone to manufacture steel wire to be knit into the lining of the airbags being mandated into every new car.

Like the cavalry, the Japanese have come to the rescue and a demoralized Larry is revived by the prospect of negotiating with Kate to sell New England Wire & Cable to the employees so it can re-tool and re-open to serve this new market – a forced smile of a coda that feels as tacked on today as it did when the film was released. The debt crisis that would soon collapse Japan's economy and the demographic one that continued it were still hidden to all but the most perceptive, and China would take over Japan's role by the end of the '90s – with ultimately the same results, though writ much larger.

Near the end of the picture Kate tries to tell Larry that he's a relic of a passing era on Wall Street: "Drexel's gone under, Milken's in jail, Trump's waiting tables." It's worth remembering that nobody is an oracle, and that even the smartest only know as much as anyone can know at one time.

Looking back at the '80s market boom in A Giant Cow-Tipping, John Weir Close writes that the decade looked like "a historical anomaly, a time so frenzied and complex that its like would not be seen again. Were it not for the 1980s, Lehman's Steven Wolitzer said, the quality and quantity of deals in 1993 would be cause for rejoicing. 'Everyone's reference point is the 1980s. But that is the wrong reference point. Never before and probably never again will M&A reach such heights.' Mr. Wolitzer would turn out to be wrong."

(Lehman Brothers itself would not survive the subprime bust.)

Michael Lewis would leave Salomon Brothers in 1988, while the pillars were falling all around him on Wall Street (but not at Salomon Brothers – not yet.) "When you sit, as I did, at the center of what has been possibly the most absurd money game ever and benefit out of all proportion to your value to society...what happens to the money belief?" he writes in Liar's Poker (like so many others unable to imagine the future).

"For some, good fortune simply reinforces the belief. They take the funny money seriously, as evidence that they are worthy citizens of the Republic...It is tempting to believe that people who think this way eventually suffer their comeuppance. They don't. They just get richer. I'm sure most of them die fat and happy."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.