Like most people who've lived more than five decades, I have a few regrets. Some are deep and personal and as such none of your business. But some are less severe and can be borne lightly: prime among them is that, while I had the opportunity countless times, I never ate in an Automat.

I had every chance; the last Automat in New York City, at 42nd St. and Third Avenue, closed in April of 1991, by which point I had been visiting the city every few months for a couple of years. It had fallen steeply since its heyday in the '40s – in a New York Times story one Halton Adler Mann, described as "an Automat fan who lives on the Upper West Side", said that "the chicken pot pies had become a dried-out gelatinous mess...You couldn't get the warm apple pie with vanilla sauce anymore, the cream spinach tasted as if it were canned, the stewed tomatoes had lost their real tomato flavor, and the chocolate milk cost too much."

The iconic cafeteria had become insalubrious, and my dining companions would have included more than a few bums nursing a cup of coffee or "condiment soup" made with free hot water mixed with ketchup and mustard packets. But knowing what I do now about the Automat's historical and cultural importance, it would have been worth it to bear witness to something peculiar to the 20th century before it disappeared, probably forever.

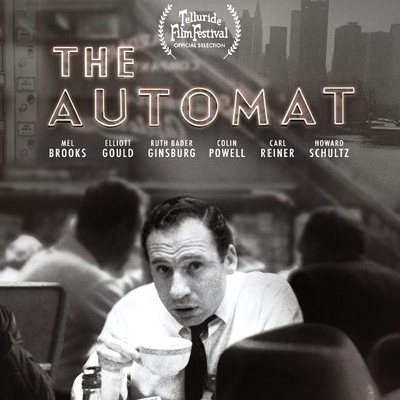

It's been over three decades since that last Automat closed but its mythic status lingered enough to inspire Lisa Hurwitz to direct a feature documentary celebrating its history and lamenting the passing of everything that made the Automat possible. Released in 2021 after a decade of research and interviews, the film is that rare thing – a successful independent documentary, thanks to Hurwitz' legions of backers and relentless programming at every festival, repertory cinema and screening opportunity the director could find.

The Automat begins with director Mel Brooks talking to Hurwitz on the phone while the camera shows her driving through snowy upstate New York to a warehouse in the middle of nowhere where the last remains of that last Automat are stored – the wall-mounted dispensers with their revolving drums, coin slots and brass-trimmed glass windows that were the point at which the public interacted with the technology that made the Automat such a wonder.

The next person we meet is John Romas, VP of engineering for Horn & Hardart, the company that owned and operated Automats in New York City and Philadelphia. He's the owner of that trove of Automat machinery in the dusty warehouse, and probably the most vital link between the company at its height and what little we know about it today. (Romas, who was in charge of closing the last Automat, would die before the film was finished.)

The Automat began with two men – Joseph Horn, and Frank Hardart, who opened a small chain of conventional restaurants, not in Manhattan but in Philadelphia, in 1902. As famous as their business would become, it would never really expand outside the two cities, and while New Yorkers called it the Automat, Philadelphians would know it as Horn & Hardart. Horn, who hated New York as much as he loved Philadelphia, presided over the company from there, while Hardart was in charge in New York until his death in 1918.

Frank Hardart discovered the "automatic restaurant" in Europe, and had the machinery imported to Philadelphia, where it was refined before they opened their first Automat in New York City. They had the little brass-trimmed windows and the coin slots but the trademark touch that everyone still talks about is the coffee spigot – a baroque dolphin's head inspired by Italian fountains that poured a cup of coffee with a shot of cream when you inserted your nickel.

One of the reasons why the Automat has lingered in the popular imagination – and why I even knew about it growing up in Canada – was how quickly it entered popular culture, and the movies in particular. An Automat appeared in silent movies as early as The Belle Epoque (1902) and The Early Bird (1925), a silent comedy about a romance between a milkman and a slumming society girl.

The Brooklyn-born Brooks is deputized to stand in for everyone who's alive to remember the Automat in its heyday. He recalls his older brother doling out nickels during visits to the city across the East River, stressing that since his family was poor, the Automat was one of their few luxuries. Lisa Keller, a New York historian, makes the point that in an immigrant city the Automat provided good food for cheap, with the added benefit of having no printed menu – you could pick your meal visually, through the little glass windows.

It was also a safe and reliable dining option for the women who were flooding into cities like New York and Philadelphia; the exponential boom in stenographers employed in businesses – the pre-digital human equivalent of word-processing and spreadsheet software – preferred to eat their lunches and dinners in clean, crowded, well-lit spaces like the Automat, and they helped Horn & Hardart's New York operations grow far faster than those in Philadelphia.

Irving Berlin would help immortalize the Automat in Face the Music, his 1932 musical where rich New Yorkers suffering from a downturn in their fortunes during the Depression dine at the Automat to the tune of "Let's Have Another Cup of Coffee". The Automat would be a setting in films like Artistic Temper (1932), Sadie McKee and Thirty Day Princess (both 1934), Wild Money and Easy Living (both 1937), The Sleeping City and Mister 880 (both 1950), Just This Once (1952), Affair with a Stranger (1953) and The Catered Affair (1956).

Single city worker Doris Day would chat with her roommate, an Automat employee played by Audrey Meadows, through one of the little brass-trimmed food windows in That Touch of Mink (1962). Jack Benny launched a TV series in 1960 with a gala party at an Automat, handing out rolls of quarters to guests as they arrived. Edward Hopper captured its nighttime mood with his 1927 painting "The Automat".

During its decline the Automat could be seen in films like Francis Ford Coppola's directorial debut You're a Big Boy Now (1966) and Woody Allen's Radio Days (1987), and even after it was gone an austere Automat would appear in the dystopic steampunk noir Dark City (1998).

And Marilyn Monroe would namecheck the Automat in Jule Styne and Leo Robin's "Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend", her big number in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953). It's hard to imagine anything codifying pop culture legend status more than that.

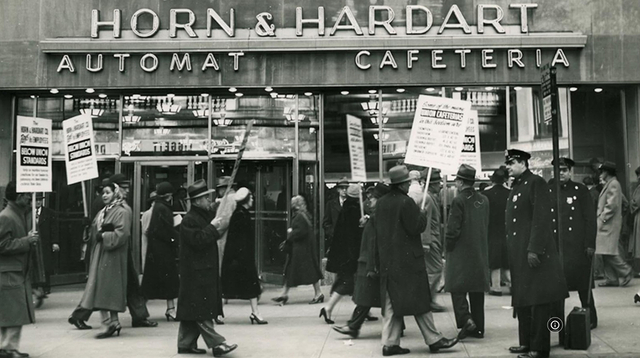

The heyday of the Automat began during the Depression, when a clean and affordable place to eat was at a premium, and lasted through the '50s. (The company survived an attempt at unionization in the mid-'30s.) During World War Two the company got the contract to provide food for troop ships leaving New York for Europe.

One of the statistics in The Automat that sticks with me is that, by the early '50s, it was feeding 800,000 people a day in the two cities where it did business. Besides the cafeterias, the company also ran a chain of retail stores under the slogan "Less Work for Mother," where customers could buy food prepared in their central commissary kitchens.

The success of the Automat was inextricably linked to that of the two urban centres where they operated, and as long as they thrived the Automat did. The company was as paternalistic as any other large business at the time, and their corporate ethos harked back to the beginning of the century: Automats didn't share branding or design, and individual locations would feature either the stained glass and lavish belle epoque touches of the early years or the streamlined Art Deco style of their great expansion.

But they were famously clean and well-run, the little windows constantly stocked with fresh food (coffee and fresh-squeezed orange juice was thrown out two hours after they were made). The biggest cafeterias had vaulted ceilings with mezzanine seating and the tables were topped with marble. Big windows let in light that gleamed off the polished metal of the Automat's machines.

Prices were kept down thanks to vast economies of scale and based around the nickel as a unit of exchange; the twenty nickels you'd get from breaking a dollar could pay for a feast. When postwar inflation and competition from the Chock full o' Nuts chain forced the company to double the price of a cup of coffee from a nickel to a dime (their machines couldn't accept pennies) it was the beginning of the end.

The five-cent coffee was iconic especially as it outlived the nickel subway admission and local payphone call, and when Joseph Horn's successor as CEO, Edwin Daly, was finally forced to raise the price after years of resistance, he had a nervous breakdown that led to his death in 1960.

When suburbanization overtook the cities in the '50s, the Automat began losing its all-day clientele, and its reluctant transformation into a lunchroom broke the business model. The hollowing out of big cities like New York and Philadelphia started a vicious circle: fewer residents meant closed businesses and increased crime, and all-day places like the Automats became magnets for vagrants.

By the '70s an episode of Barney Miller would have the show's detectives leave the squadroom to deal with a naked man in an Automat. The original Horn & Hardart location in Philadelphia, opened in 1902, closed in 1968 and the death of the Automat after that would be slow but relentless.

In interviews with customers like Gen. Colin Powell and Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, The Automat paints a picture of the cafeterias as a model of democracy in action. In the '30s they were depicted as a great leveler, where anyone could be found at a table, spending the same nickels for the same food. The experiences of Powell and Ginsburg are meant to prove that the Automat's business ethics were practical yet utopian: capitalism built on the broadest possible market base, indifferent to everything except the nickels pouring through their machine's slots.

The popularity of the Automat in books and magazines, in movies, TV and cartoons gave it unprecedented cultural reach, broad enough to lodge in the imaginations of someone like myself and The Automat's director Lisa Hurwitz, despite neither of us ever setting foot in one.

There are hardly any direct equivalents for the Automat in America outside New York and Philadelphia, never mind in the rest of the world. Britain had Lyons' Corner Houses and the humble caff; in North America the diner or "greasy spoon" would grow and thrive during the same period as the Automat, and minus the gleaming machines they're the closest thing I can compare to the Automat in my experience.

My own employment history is tied into cheap food; after flipping burgers at McDonalds for a couple of summers I got a job in the employees' cafeteria at the flagship store of Simpsons, one of Canada's two big department store chains. The employees' cafeteria was one of the last vestiges of corporate paternalism – cheap food produced in the same kitchens that cooked for diners eating on white tablecloths in the store's upmarket Arcadian Court, sold at a deep discount to workers fueled by huge urns of coffee and tea. Their disappearance ended a social contract between companies and their employees that lasted more than a century.

And like most young people living marginally on low wages or freelance income, I was sustained by the diner, at least one of which could be found in any pre-gentrified neighbourhood. They might have been independently-owned and run – often by families – but they shared a common menu and prices and were charmingly free of updates in décor from whenever they were opened. (Like most of Generation X, I saw enough of the urban renewal of the '60s and '70s to develop a taste for anything and everything deemed retro.)

I can still remember them – greasy spoons like the Skyline, The Varsity, People's Foods, The Canary, Seniors, The Brothers and especially The Stem. Thin profit margins and skyrocketing rents along with gentrification have sent them into the sunset – even in New York City, where they are considered as iconic and culturally essential as those long-gone Automats.

The Automat is fueled by sentimentality and nostalgia and the idea that something indefinable has been lost in how we live together in cities – a tone it shares with so many documentaries funded by documentary film and public broadcasting foundations, though thankfully without the relentless pop ideology you find in PBS programming.

The question lingering at the end of the film, though, is what replaced the Automat and could it be recreated, for which the answers are essentially "not much" and "no." The current owners of the Horn & Hardart and Automat trademarks claim that they intend to relaunch the restaurant, but so far that's just words on a website. Starbucks founder Howard Schultz, a native New Yorker who ate in Automats as a child, insists that he filtered his memories of them into the creation of his coffee chain.

He describes the success of the Automat as a kind of magic and insists that Starbucks is touched with a bit of that, but it sounds like wishful thinking. In the theme song for The Automat that Mel Brooks wrote and sings over the closing credits, he takes a swipe at Schultz' coffee empire:

"You have to understand they

Had no latte grande

No quizzical baristas in your way"

Speaking for everyone who actually ate in an Automat and cherishes the memory, Brooks calls it "a great experiment," and regretfully concludes at the end of the film that "it can't work again because the logistics and the economics of today won't allow anything that simple, naïve and eloquent and beautiful to flourish again."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.