According to Russia's civil aviation agency, Wagner chief Yevgeny Prigozhin was listed as a passenger on board a private plane that crashed earlier today 60 miles north of Moscow.

Others speculate he was actually on board a second plane flying over Moscow and may still be alive...

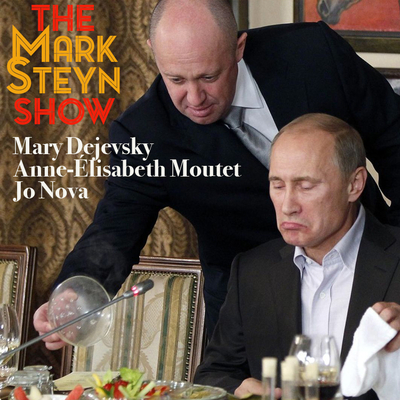

Two months ago, Mark discussed Prigozhin with former Moscow correspondent Mary Dejevsky on The Mark Steyn Show.

Below is a transcript of that conversation.

Mark Steyn: Hey, Welcome along to a brand new week of the Mark Steyn Show. We have three of my favorite guests returning to the show tonight from across the planet. Former Moscow correspondent Mary Dejevsky will try to make sense of whatever the hell that was in Russia over the weekend. The doyenne of Parisienne commentatrice is here, Anne Élisabeth-Moutet and from beautiful Perth in Western Australia, Jo Nova is back with us.

So I swung by the Brownstone Institute website the other day and they had a column by David Thunder called "Informational No Man's Land." There it is, if you want to place it on the map, it was about the loss of public trust in media and official sources. The author is talking about the COVID years. And you'll know what he means. A week ago, we discussed that new study from America's super prestigious Cleveland Clinic, showing that the more COVID vaccine boosters you get, the more you increase your chances of getting the COVID, which isn't quite what the experts were saying two years ago. The conspiracy theories that got you banned from Facebook and YouTube in 2020 are now the conventional wisdom and the conventional wisdom of 2020 that the coronavirus came from a bat or a pangolin—remember pangolins? Yeah, look at that cute little fellow. They were all the rage three years ago. 2020 was the Chinese year of the Pangolin and no counter narrative was permitted.

Now it seems that a weird new coronavirus in the town that hosts China's number one coronavirus laboratory did in fact come from that laboratory. We'll get into that a bit later with Jo Nova. But once you have a breakdown of public trust in governments and media, it's hard to keep that confined to some wacky respiratory virus. So what Brownstone calls the Informational No Man's Land has expanded considerably since 2020. Which brings us to Saturday, when the world woke up to discover that a coup was underway in Russia. It was led by this scary looking fellow. Yeah, that's the new Gollum in The Lord of the Rings reboot. Oh, no, wait, my mistake. It's Yevgeny Prigozhin, head of the Wagner Group, which comprises some of Russia's most effective fighters in Ukraine, as in Syria and Central Africa.

They started the day by seizing Rostov on Don, a city of over 1 million people and the headquarters of Russia's Southern Command, which is running the Ukraine war. That's way down in the south of the country near the Ukrainian border, and the Sea of Azov, a dramatic start to the morning even if what it all meant was a bit open ended. I précised the two most basic possibilities on Saturday thus: A) the Ukraine war is over, with Russia's least worse soldiery marching on Moscow what's left on the Western Front can't do diddly. Alternatively B) the Ukraine was about to metastasize. They are generals in the Kremlin, awaiting Prigozhin with open arms because like him, they're itching to nuke Kiev.

So I went off and made myself a cup of tea and came back to find the mutineers were now half way to Moscow, which is impressive. But even so, there's only an estimated 25,000 of them. They can't take over a metropolitan area of 22 million people can they? Not when the other guy Putin is the only one with an Air Force. So I had another cuppa and returned to find that this guy Prigozhin was 300, 250, 200 miles from Moscow, at which point he suddenly decided to throw in the towel and go into exile in Belarus, which believe me and with no disrespect to our viewers in Minsk or anywhere else, is no place you would want to go into exile in, but that was that and the cable news stations went back to Trump indictments and transgenders shattering the glass ceiling.

So what exactly just happened? It doesn't really make sense from either the Putin end or the Prigozhin end but maybe Mary Dejevsky can figure it out for us as she has before. She was a respected Moscow correspondent for The Independent and is now their foreign affairs columnist. Mary, what just happened in Russia?

Mary Dejevsky: Well, what just happened certainly kept us all extremely busy through the weekend and even through half of today. I don't think what happened was an attempted coup, it was an attempt to change and make more efficient and more effective Russia's military policy and Russia's war in Ukraine. It wasn't designed to topple Putin; it was designed to change his policy and to change some of the people at the top of the war operation. But it failed. Or at least, it looks as though it's failed so far. Because today, we've seen on video, the defense minister who was one of the people that Prigozhin was trying to dislodge, we've seen him on video apparently doing his job. Now, we don't actually know whether that was today. But putting out that video sends the signal that he is still there.

So to that extent, Putin is still there, the defense minister's still there. There's been a Cabinet meeting this morning, at which point, something really interesting emerged, which is the prime minister, calling on Russians to show a degree of unity, and to rally around the president. Now, if you had not been particularly interested or concerned about Putin's authority until that particular moment, from now on, I suspect that you will be, because if the Prime Minister is calling for everybody to rally around the president, what does that say?

Mark Steyn: So, the idea, therefore, is that Prigozhin actually had no desire to topple Putin. He merely wanted an incompetent war leadership to be replaced. And as you say, Putin, for whatever reason decided to stand by these guys. Is it really that hard, a year into a war to find alternative generals in Moscow? Or is Putin actually quite content with the way this war is running?

Mary Dejevsky: I don't think there are very many signs that Putin is particularly content with how it's going. The question is, if it could go worse if other people were in charge, or if it would go in a way that was contrary to Putin's final objectives. And it looks as though the people who were on Prigozhin's side, they wanted a much more active, much fiercer tougher policy towards waging the war in Ukraine. You know, the idea that somehow Prigozhin represents an alternative policy in terms of something that either Ukraine or its Western allies would be more likely to support. That is completely wrong. That is completely the opposite of what Prigozhin would mean, Prigozhin wants a much tougher attitude to waging the war in Ukraine, and possibly to occupy the whole of Ukraine, or to have the war over with the Russian victory much faster than is currently happening. But that is not what obviously what Ukraine wants and it's not what Ukraine's Western allies want.

Mark Steyn: Well, just let's just let's explore that a bit. From the point of view of the West, you know, we've had Joe Biden caught on camera calling for regime change in Moscow and I agree with what you say about Prigozhin and how his allies want to actually up the ante on Ukraine. I mean, you know, in ways that make Putin look measured and restrained, isn't that the reality of this situation that Biden and all kinds of other people can call for regime change in Moscow, but whatever regime, you change it to is likely to be worse?

Mary Dejevsky: Absolutely. Which is why I think one of the one of the theories doing the rounds, one of the more interesting theories doing the rounds, is that Prigozhin is somehow being used or in cahoots with Western intelligence to topple Putin. Now, if there is any truth in that, which I doubt, other than that it's possible that there were some sort of links and communications, as there often are. The idea that anybody associated with Western intelligence would think either that Prigozhin was preferable to Putin from the Western perspective, or that disorder, chaos, leaderlessness in Moscow was somehow preferable to what's going on at the moment. You know, I would find that extraordinary if that was any estimate, anywhere in Western intelligence.

Mark Steyn: But just let me ask you about that, because you had people on your Twitter feed over the weekend who were claiming that this was all theater. And, you know, I had comments from people who said, "Well, you know, look at that $6.2 billion, American money that was supposedly the victim of an accounting error in Ukraine, suppose they offered Prigozhin $6.2 billion to march on Moscow, and he notified Putin, they offered to split it between them, and staged a bit of coup theater." So let me ask you a bit of the most basic question here. It wasn't a coup, because I would have thought in Moscow any coup against Putin is going to start in the Kremlin, with big shots around him who decide he's done in the way that it often happens in other countries. But do you think that the Wagner group's rationale for this was genuine and they were genuine in the actions they took?

Mary Dejevsky: Well, I think you can certainly, you can certainly see a genuine reason why Prigozhin and his Wagner people would take that sort of action, because they were under a threat from the Russian Defense Ministry and the top brass, that instead of being a sort of autonomous force under Prigozhin of around 25,000 people, that they should all sign contracts to be under the discipline and under the terms of the Russian regular military. This is something that Prigozhin has deliberately avoided; he wants to keep his autonomy. He cooperates as and when with the central government and the authorities. But the impression very much is that he is his own person. And he wants the freedom to do his own thing. He and Wagner, his mercenaries have been very active in parts of Africa. And of course, there's a possibility that if Prigozhin does leave Russia, he might not go to Belarus, but he might actually go and sort of focus on his African activities instead. But I think the idea that his mercenaries, his force, would have to subordinate themselves to the central authorities in Moscow. That was something that he and they objected to, and could very well provide a reason for marching on Moscow and demanding some sort of change at the top of the Defense Ministry, most of all, to drop that particular requirement. What's interesting is in the agreement that we know very little about, but one of the things we've been told about that agreement, brokered by Lukashenko of Belarus, is that those Wagner forces will indeed be required, essentially, to join the regular Russian Army. And that is part of the price, maybe for Prigozhin remaining a free man, albeit maybe banned from Russia, we don't know.

Mark Steyn: Well, let me ask you about what was said by some to be the most disturbing aspect of this. As you say, the official estimate is 25,000 in this group. They took over a city of 1 million, including the headquarters of the Russian Army's Southern Command. Was that a genuine takeover? Because if it if it is, it would not seem to speak well, for the Russian Army but on the other hand, you know, is that too just a form of theater? Did they genuinely take The Southern Command Headquarters?

Mary Dejevsky: Well, I think I would put it slightly the other way round, in the sense that what appears to have happened is that Prigozhin apparently ordered his forces who were on the Ukrainian side of the border to cross back into Russia. And Rostov is not many miles from the border, and they reached Rostov. But I don't think they made any attempt to occupy or actually capture the city, you know, I've heard that term used. But I don't think that's what they did. What they did was they took over which, in some ways, may be worse from the perspective of central control from Moscow, they took over the base, which was the nerve center for Russian operations in Ukraine, and they took over the military airfield. They didn't really need to take over anymore, because that gave them that gave them control of what they wanted, their focus is on military things. It's not on the civilian population. And so when they left or a part of their convoy left to go north, they apparently did something similar in at least a couple of the places along the route, you know, quite big cities—Voronezh was mentioned, Lipetsk was mentioned. And they didn't need to take over the cities, what they needed to do was, as it were, to establish control of the military facilities, the military infrastructure of those places. And what is surprising to me, and I suspect is probably surprising to quite a lot of other people is that the commanders and the people in charge of those bases and those facilities appear to have agreed to hand them over, without any resistance, whatever. And one reason for that may have been confusion; one may have been a lack of orders from the center. Another may have been that the Wagner people and Prigozhin have, until the last couple of weeks, really been allied to Moscow, and to President Putin. They were the ones on the front line, who won the enormously long and brutal battle for this place called Bakhmut in the northeast of Ukraine. And so the central government has something to thank them for, and they were in alliance. So it may have been that the military in Rostov and the military in Voronezh and other places simply weren't aware that there's been this sort of big divisions, big split between Moscow, Putin, and Prigozhin on the other hand.

Mark Steyn: Well, just to extend that thought, you know, the conventional wisdom is that Prigozhin and his guys are much more effective, not just in Ukraine, but elsewhere than regular Russian troops. So what is the thinking behind essentially dissolving their rather effective autonomy and merging them into the Russian army, which at least as we hear it on the BBC, and CBS and NBC, are just a bunch of duds who can't do anything in Ukraine? Why would you get rid of your, you know, it's like the opposite of what you do at this stage in the war, you take your most effective fighting force and make them as worthless as your other fighters. That would be the takeaway, if you were following the BBC or CNN analysis. So what's the Russian thinking behind this move?

Mary Dejevsky: Well, I think that's a perfectly good point. And a supplementary point to that would be that, do you really want to incorporate into your forces, not only people who may be more efficient and better at their job, but who may not actually want to be there under that particular command? Is that going to make Russia's fighting force in Ukraine any more effective, but I think there was the bigger argument which probably prevailed in Moscow was, "Do you want a part of the force that's fighting on your side in Ukraine? Do you want that outside of the central command?" And does there come a point where there's a risk of maybe them going their own way? So I think maybe that was the point that that won out.

Mark Steyn: What about—which, I guess is the ultimate question here—what about the dispossession of the Russian people? We all remember that, you know, famous scene from 30 years ago of Yeltsin standing on that tank during the attempted coup against Gorbachev. In this case, the people of Rostov there's, you know, footage that you can see those happy smiling Russian girls taking selfies in front of the tank. There's people handing out drinks and confectionery to the Wagner group, guys, what's the general vibe on the ground re the war and Putin's government?

Mary Dejevsky: I think it's very, very difficult to gauge that. I think there's evidence, certainly of opinion in the Russian border areas, where Ukraine has inflicted some strikes around a place called at Belgorod. That the population there feels, to an extent unprotected and undefended by Moscow, which has shown very little interest in them. And there's been some sort of social media evidence from that part of Russia, that people have been saying, "Well, you know, if Putin, if Putin isn't prepared to defend us, then maybe Prigozhin is" and evidence too that maybe he's been capitalizing a bit on that sentiment. But it may also be that because, you know, the spread of information in Russia at the moment is both censored, not very effective, and in, in different channels, so different people, know different things, that those people who were welcoming Prigozhin in Rostov, and who gave him and his forces such a fond farewell, that they may not have been completely aware that they were that they'd split from Putin and the center. And, you know, the same may be true in Moscow and in the cities as you went north. You can make the argument that Russians might prefer somebody who looked, who had proved a degree of success on the battlefield, as opposed to the current defense establishment and top brass that they might have seen as failing in the battlefield. But nonetheless, to see Prigozhin and his mercenaries, which is a relatively, it's not an inconsiderable number of people, but it's not a huge number of people, to see that as somehow equivalent and preferable and maybe a replacement for the military, under the, under the Russian government. You know, that is quite difficult to accept as a rationale.

I would also say that if you look back to the coup of 91, and you envisage Yeltsin on the tank all over again, Yeltsin had a big history, he had been elected president of Russia, he'd been, he'd been out speaking, campaigning, he was a big public figure, equivalent, and really on an equal and gradually surpassing Gorbachev in authority. And after the coup when Gorbachev came back, he came back as a diminished figure, that power had tipped from Gorbachev to Yeltsin while he was away. It's very difficult for me to see Prigozhin as an equivalent, if you like to Yeltsin with power being able to so easily to tip from Putin to Prigozhin, it doesn't seem to me that the two are in any way comparable.

Mark Steyn: No, that's certainly true. It's interesting though, the reaction on the streets, Rostov is just a very short drive across the border to Mariupol. Which, and if you were thinking in....if you were in Rostov, and you were thinking this war isn't going so well, you certainly wouldn't want your town to end up the way that Mariupol has done compared to a year ago. Thank you very much, Mary. It's always good to get your take on this. And as I said, it was all very exciting on Saturday, and then what happens is, okay, what the hell was actually going on all that time? And I would be interested to know the contacts between the one side and the other in the Kremlin as that was all happening. Thank you very much Mary Dejevsky, we always appreciate your take on these things.

The full show can be viewed here.

Tomorrow, Laura's Links returns to SteynOnline. You may also catch up with Mark's latest Tales for Our Time here.

~If you're a Mark Steyn Club member, feel free to disagree in the comments section - but please do stay on topic and be respectful of your fellow members; disrespect and outright contempt should be reserved for Mark personally. For more on The Mark Steyn Club, please click here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership.