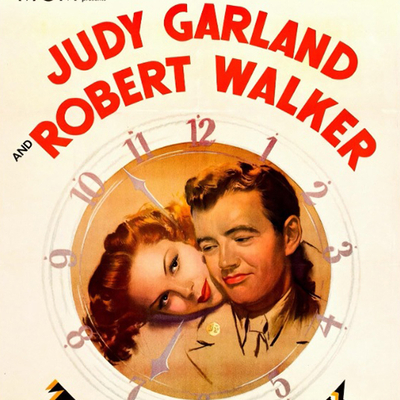

The abiding reputation of Vincente Minnelli's romantic drama The Clock (1945) is the result not just of the fact that it might be among the best work the director and his star (and future wife) Judy Garland ever did, but that it still resonates despite the very specific moment in which it was produced.

Because there are a lot of films where phrases like "Is this journey necessary?" or "Closed for the duration" or "You're short on points" require footnotes for generations born decades after they were inescapable – as they were in the cartoons and shorts and lesser pictures that filled screens when The Clock was released.

But The Clock, like Casablanca or A Guy Named Joe or Since You Went Away or I'll Be Seeing You, is a story about people in a war more than a war story. It might, in fact, be the greatest example of such a thing since it happens thousands of miles from the front, in a place where war is context not setting, at the moment when it was impossible not to imagine the world after that war.

Minnelli and Garland, who had resumed an affair while making the film together, were married less than a month after the film was released, and their wedding gift from studio mogul Louis B. Mayer was three months' vacation in New York City for a honeymoon. Days after arriving the city was jammed with crowds celebrating General Dwight D. Eisenhower's triumphal return from Europe after the defeat of Germany, and before their honeymoon was over they'd see the streets fill up again for V-J Day.

Which was fitting as The Clock is one of the great movie portraits of Manhattan, the city where Minnelli had his first flush of success as a set designer and theatre director before being tempted by Hollywood, arriving just in time to join the legendary production unit forming around Arthur Freed.

The film begins in one of New York's lost legendary places – Pennsylvania Station, or rather a huge, impressive replica built on the MGM sound stages when Fred Zinnemann was the director. He'd been fired and production halted but The Clock was Garland's pet project, the chance to prove herself as a dramatic actress, and desperate for someone to take over she turned to Minnelli, who had more than exceeded her low expectations a year earlier on the first film they did together, Meet Me in St. Louis.

The camera hovers above and around the crowded station before finally settling on just one Army corporal, Robert Walker's Joe Allen, just arrived on two-day leave from training camp in Aberdeen, Maryland. (The location hints that Joe is artillery, the insignia on his uniform that he's in a tank destroyer regiment.) Joe, we quickly learn, is a bit of a hayseed, disoriented and even frightened by the scale of the city outside the train station, where he retreats to get his bearings. Simply put, and paraphrasing the old Bunny Berigan hit, Joe can't get started.

Joe is such a hick that he can't contain his excitement while riding one of the station's escalators. Driven back inside by the thronged streets and concrete canyons, he maroons himself by that escalator, which is where his outstretched leg trips Alice Mayberry (Garland), a secretary arriving back in the city after visiting her family, making her lose the heel on her two-toned pump.

It's an awkward meeting that Joe is desperate to extend, despite Alice's obvious reticence. A hayseed like Joe, she's been in the city for nearly three years and has learned to be distrustful – especially with any man in uniform, and Minnelli fills the station and the streets outside with plenty of them. Walker plays Joe as more lonely than horny, and his longing for company and a guide to get him through two potentially overwhelming days overcomes Alice's doubtless hard-earned wariness.

Minnelli, an enigmatic and soft-spoken man both on and off set, helps Walker and Garland create a sense of intimacy virtually from the moment they meet, starting with those two-toned pumps. Appalled at his clumsiness, Joe takes the broken shoe off Alice's foot after lifting her onto a marble banister, then supports her while frantically trying to find a shoe repair shop in the station.

Garland takes the shoes off again as she tucks her legs beneath her while they sit together on the podium of an Egyptian statue in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. (It was apparently once acceptable to use ancient sculptures as benches in major museums.) The pair respond to some urgent need for contact and physical rapport with each other, even while trying to remain polite or prudent with a stranger.

This is essentially the whole of the drama of The Clock, a remarkably simple story fleshed out not just by countless plot contrivances but by the heartbreaking performances of Garland and Walker.

The emotional instability that would afflict Garland for her whole career is part of her legend, but Walker's own tragic story is less known today, mostly because alcoholism and mental illness would end his short career in 1951, of an accidental overdose at just thirty-two. Ironically it was Garland who would help Walker make it through shooting for The Clock; along with her publicist Betty Asher and her friend and make-up artist Dottie Ponedel, the actress would search for Walker when he disappeared on a binge, nursing him sober again while hiding these rescue missions from Minnelli.

The instability and neuroses, hidden in plain sight once you know about Walker's sad personal life, are probably what helps him get across Joe's vulnerability – the key to helping us sympathize so quickly and deeply with the young soldier, which could have remained submerged behind the unvarnished veneer of the stock hick character.

The Clock might be the pinnacle of Garland's career; filming it was certainly the least emotionally fraught, despite her growing addiction to pills. She had finally made headway breaking out of her juvenile image with Presenting Lily Mars (1943) but had worried that playing Esther Smith in Meet Me in St. Louis would be backsliding. But Minnelli, along with Ponedel and cinematographer George Folsey, brought out the glamour Garland had longed for in her image. As Emanuel Levy writes in Vincente Minnelli: Hollywood's Dark Dreamer:

"Minnelli became the first director to make Judy look and feel beautiful, and for that she would remain eternally grateful. In no other film did Judy look so beautiful. It was Minnelli's idea to make her eyes more expressive by applying white eyeliner to her lower lids."

As overseen by Minnelli, Garland had actually grown up in front of audiences in Meet Me in St. Louis, transforming from girl to woman over the course of the year covered in the story of the Smith family. But Alice Mayberry is a woman with a job, a roommate and agency, living away from her family in the biggest city in the world.

She chooses to provide company and emotional solace for the naïve and lonely young soldier, and even after her roommate Helen (Ruth Brady) convinces her to stand up Joe for the date she's made to meet him under the clock in the lobby of the Astor Hotel, she changes her mind at the last minute.

Their journey through the city begins here, starting with dinner in an Italian restaurant where they have their first fight, and leading to a scene in Central Park where they're forced to confront the feelings growing between them.

Writing about the film in The New Yorker, Richard Brody calls it "one of the greatest ever filmed." Joe notes how quiet the park seems, but Alice asks him to stop and listen for all the sounds of the city, forcing us to join the intimate circle that's been growing between the two young people.

"Minnelli," Brody says, "crafts an extended and complex series of images of furious stillness and graceful, nearly balletic maneuvering until the lovers converge and kiss, under the glow of streetlights, in a matched series of some of the most ecstatic closeups I've ever seen. At a moment of most fervent passion, Garland's right eyebrow twitches, and that tremor – magnified by Minnelli's rapt scrutiny – resounds visually like a crashing wave of uncontrollable desire."

"The Clock feels like the closest thing to an erotic documentary that Hollywood could offer at the time of the Hays Code; the fact that it was released uncontested suggests the insignificance and feebleness of the code, and, even more, of directors who took its dictates as constraints on their art."

Film professor Steve Vineberg, writing about the film for the Critics at Large blog, observes that "Minnelli stages and shoots it as if it were a duet, and when Alice draws Joe's attention to the sounds of the city that never entirely fade, even in the middle of the park, a choir emerges out of that hushed cacophony."

Writing about the scene in his book, Levy notes that "George Folsey captured her face lovingly and expressively. For the first time, Judy revealed onscreen that special glow of hers. People who say The Clock held that because of that scene it was obvious Minnelli was deeply in love with her. Not surprisingly, the shy Minnelli expressed his strongest feelings for his leading lady through his camera."

It's hard not to reach this conclusion; the scene, lit in glowing highlights against deep shadows, is as ardent and delirious as anything in the lovestruck films of Frank Borzage. It's also the fulcrum on which the film turns – their love acknowledged, the rest of the film is a test of their resolve and willingness to follow their feelings.

Emerging from the park Alice realizes they've missed their last bus but get a ride back downtown in a milk truck driven by Al Henry (James Gleason), on his way to start his shift. He gets a flat and has to call for repairs in an all-night diner where a hyperarticulate drunk (a brief but fantastic performance by Keenan Wynn) accidentally decks Al.

The young couple step in and help him finish his rounds, then join him for breakfast back uptown with his wife (Lucile Gleason – James Gleason's real-life wife). Joe watches Alice help with breakfast, his silent gaze letting us know that they have to make a decision quickly. Chance has brought them together and allowed them to enjoy every minute of his leave, day and night, but like any young person they know they want more.

After getting separated in the labyrinth of the New York subway system, Joe and Alice find each other again and realize that they need to get married, which means a desperate lunge through the bureaucracy of the city's municipal government. Taken together with their misadventure on the subway, this part of the movie is nothing less than a journey through the city's alimentary canal.

For every obstacle and deadline there's a potential workaround set against the relentless ticking of the clock and the end of Joe's leave – the meaning of the film's title is stark and hard to miss. After racing around to get forms and blood tests they finally take their vows in front of a justice of the peace while the elevated subway roars past the office windows behind him. Sitting in a greasy spoon afterward they try to hide the realization that it was all a bit tawdry despite their efforts.

"It was so...ugly," Alice tells Joe with a shuddering sob, in what is probably Garland's second most affecting scene in the picture.

The couple wander the streets and come across another wedding – a groom in an officer's uniform, a bride in white, leaving a church ("Saint Faith Episcopal Chapel"; a generic holy place) surrounded by friends and family. They enter and sit in a pew while a sexton goes around extinguishing the candles. Legally married, the young couple longs to make their union sacred, and begin reciting the marriage rites from the prayer book.

It's hard to imagine this scene in any movie today.

We find Joe and Alice again in a hotel room the next morning, at another breakfast, with the city rooftops spread out in the windows behind them. It's a post-coital moment of triumph, but we know it'll be a brief one. In the park two nights before he'd pointed out the ships in the East River – a convoy, probably heading for Europe; he might not come back, or he might not come back whole.

A film fan's mind might wander to William Wyler's The Best Years of Our Lives, just a year in the future, to Dana Andrews' Fred with his faithless wife and PTSD, and Harold Russell's Homer and his prosthetic hooks. For audiences at the time there was consolation in the fact that the picture was released just over two weeks after V-E Day; they might be able to imagine that Joe would arrive in Europe in time for garrison duty in Bavaria or Berlin, before getting back on a ship home to Alice.

Judy Garland would work together with her husband again, on Ziegfield Follies (1945), Till the Clouds Roll By (1946) and The Pirate (1948), but none of these films were as good as The Clock. Their marriage would end in 1951. Penn Station would be torn down in 1964, the Hotel Astor in 1967.

When shooting was over on the picture, Garland gave Minnelli a present – a desk clock – and included a note:

"Darling, whenever you look to see what time it is – I hope you'll remember The Clock. You knew how much the picture meant to me – and only you could give me the confidence I so badly needed. If the picture is a success (and I think it's a clinch) my darling Vincente is responsible for the whole damn thing. Thank you for everything, angel. If I could only say what is in my heart – but that's impossible. So I'll say God bless you and I love you."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.