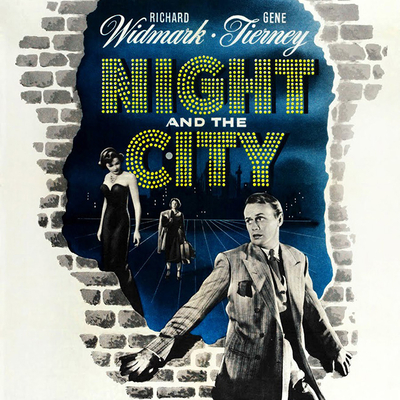

Jules Dassin's Night and the City (1950) begins and ends with a man running through darkened streets. When we first see the man it looks like he's in the kind of trouble you can't escape, and by the end of the film we know it for certain. There isn't a moment when we don't know we're watching a film noir, though Dassin insists that he didn't have a clue what that was when he made it, or the three very noir films that preceded Night and the City – Brute Force (1947), The Naked City (1948) and Thieves' Highway (1949). Even the title boils the essence of noir down to four simple words.

Dassin was in exile when he made the film after being blacklisted in Hollywood, named in testimony to the House Committee on Un-American Activities. He'd been sent to London by Daryl F. Zanuck with a copy of Night and the City, a novel by British writer Gerald Kersh, though he admits in a video interview included with the Criterion reissue of the film that he wrote the script without ever reading Kersh's book.

It really doesn't matter, as the story that both Kersh and Dassin tell is solid tragedy – a man with ambition undone by his character, with the added misfortune of setting about his desperate plans in a hard, unforgiving place. This would usually be some big American city, but Dassin's movie takes place in London, an ancient city whose pitfalls and traps seem all the more deadly as they've been in place for many more centuries.

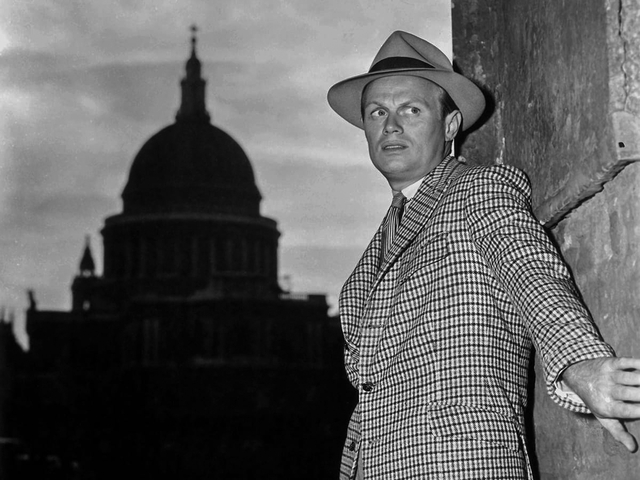

The running man is Harry Fabian (Richard Widmark), an American in London for reasons never explained. Did he choose to stay behind after the war, or is he there to escape something or someone back home? We never get an answer; everything that happens to Harry in Dassin's film is of the moment, the result of his hasty choices and actions – none of which, we quickly learn, are wise ones.

He's run to ground at the apartment of his girlfriend, Mary (Gene Tierney). Where Harry is devious, Mary is honest, and we have no idea what she sees in him except for a snapshot taken years earlier when their lives weren't as dire – and the woeful certainty that some women are irresistibly attracted to cads.

Harry has a rival for her affections – Adam (Hugh Marlowe), another American, living in the loft apartment of her building. He's a creative type, bohemian and unconventional, his tiny flat littered with his attractive handiwork, and apparently quite prosperous by freelance standards. When she asks for a few pounds to help Harry pay off the man waiting for him outside Adam reacts with doleful resignation; even he seems to understand the appeal Harry might have for Mary – he calls him "an artist without an art" – and hands over the money.

Freed from his pursuer, Harry and Mary can head off to work. She's a singer at the Silver Fox, a Soho "clip joint" owned by Nosseross (Francis L. Sullivan) and run efficiently by his wife Helen (Googie Withers). In her number (Tierney's voice is dubbed by actress and singer Maudie Edwards, famous as the woman who spoke the first line of dialogue in the first episode of Coronation Street) Mary sings about the joys of champagne, an undisguised prompt for patrons to add a few more bottles to their tab, while Helen ruthlessly marshals the club's servers to keep their glasses filled.

Tierney's Mary is appropriately haunted and beset, and the actress was going through one of the many rocky patches in her personal life when she made the picture. Her marriage to designer Oleg Cassini had been on the rocks for several years, and they were attempting a reconciliation when she made the picture, though after she'd had a brief affair with John F. Kennedy that she ended after he'd begun his first term as a congressman. (Cassini would design her wardrobe for the film.)

In his video interview for the Criterion disc, Dassin says that he cast Tierney as a favour to Daryl F. Zanuck – a favour he knew he owed him – and that the studio mogul was concerned about Tierney's well-being, calling her "suicidal". Dassin admits that this sort of compassionate behaviour hardly jibes with our image of the ruthless Zanuck, but he wants it on the record that it happened.

Harry works as a tout for the club – combing other bars and night spots for tourists, preferably Americans, who he gulls into more risqué entertainment with a visit to a "private club" off the beaten path. An enthusiastic grifter, it's helped him tap into the city's underground network, which he takes to as naturally as any locally born spiv.

While doing his rounds he witnesses an argument at a wrestling match between Kristo (Herbert Lom), the gangster who runs all the boxing and wrestling in the city, and his father Gregorius (Stanislaus Zbyszko), a legendary Olympic wrestler appalled by how his son has turned what he considers an athletic art into a tawdry show with goon wrestlers like The Strangler (Mike Mazurki).

He has a brainstorm; he'll use the father as a wedge to take over Kristo's market. Improvising wildly, he convinces the old man and his protégé Nikolas (Ken Richmond) that he's a great fan and as insulted as they are by Kristo's cartoonish spectacles; he reasons that Kristo will never be able to move against him as long as his own father is his partner. All he needs is a few hundred pounds to rent a gym and an office and start booking matches.

He can't gull that kind of money from Mary so he goes to Nosseross, who holds his employee in contempt as hopelessly small time. But Helen gets him to promise that if Harry can come up with £200 he'll match it, hiding a plan of her own.

Harry heads out into the night to implore his contacts for the stake – grotesques like Anna (Maureen Delaney) the Irishwoman who runs the smuggling on the Thames, Googin the forger (Gibb McLaughlin) and Figler (James Hayter), head of a syndicate of beggars he helpfully equips with fake legs and prosthetics. Dassin paints a Dickensian picture of London's underworld, which British critics called ridiculous when the picture was released, though Dassin insists that he'd been given a tour of its real-life equivalents by a friend who worked at Scotland Yard.

They all turn him down, and he's at the end of his tether until he finds Helen waiting for him in a dive. Another woman carrying a torch for Harry, she's planning to leave Nosseross, and has secretly bought her own club, though it will be another year before its probationary ban is lifted after it was shut by police. She'll front him £200 and they'll use the club to help fund Harry's fight empire; all he needs to do is obtain a license for her to re-open the place.

Nosseross adores his wife and suspects an affair with Harry, which inspires him to lay plans of his own, encouraging him to go up against Kristos and conspiring with the mobster to let Harry's deceitful nature take its own course, which they both know will lead to him betray Gregorius when he becomes desperate – a trap they lay carefully and confidently.

The casting for Night and the City is remarkable – not just with Widmark, probably one of noir's greatest actors whether playing a nominal hero or a heavy, but with the British supporting cast. Sullivan, Withers, Lom and all the secondary players convincingly inhabit a world far older than any American urban underworld.

You imagine their equivalents going about similar business while the Great Fire raged, despite Norman invaders, and all the way back to Saxon and Roman London. They have a deep larcenous history on their side, and an upstart like Harry, with his wild-eyed dreams of building an empire on their foundations, stands no chance.

But by far Dassin's greatest casting coup was Stanislaus Zbyszko's Gregorius. He had remembered a photo he'd seen as a boy, of the greatest wrestler in the world, and though he was assured that Zbyszko was dead, further inquiries discovered him alive, a chicken farmer in New Jersey – though he was actually training fighters with his brother at a farm in Missouri.

Zbyszko had appeared as himself in Madison Square Garden (1932), a pre-code fight picture starring Jack Oakie, but had no real acting experience. Dassin said he didn't care – that he was sure he could get a performance out of the 82-year-old wrestler, and the long, brutal fight scene with Mazurki near the climax of the film is proof of his confidence.

Harry doesn't disappoint his antagonists, but the catastrophe they count on goes much farther than their worst expectations of Harry's deceitful nature. Nosseross betrays Harry right on cue – withdrawing his support for his scheme in one of the only scenes filmed in broad daylight, in the middle of Trafalgar Square.

But he doesn't move fast enough to stop Helen from leaving him, walking out while he's gloating over his victory in his office, humiliating her husband with a few choice insults before she goes. But at her new club she discovers that her license is a forgery, obtained by Harry from Googin; humiliated, she trudges back to the Silver Fox through Soho's back alleys carrying her suitcase, but discovers that her husband has killed himself and left his money and the club to Molly (Ada Reeve), the crone who works there as charlady and flower seller.

When a predictably desperate Harry steals money from Mary to pay The Strangler's manager to book him for a grudge fight with Gregorius, the wrestler gets drunk and goads the older man – with Harry's tacit compliance – into an all-out brawl in the practice ring of Harry's gym. The old man wins, but the exertion does him in and Kristo arrives to watch his father die – a truly heartbreaking scene and further testament to the intuition Dassin had about Zbyszko as an actor.

Harry flees before Kristo can put a bounty on his head, and nobody wants to collect it more than Mazurki's Strangler, to redeem himself for helping kill the old wrestler, though Harry's network of criminal "friends" do their best to beat him to the prize. One of the best scenes in the film involves a camera locked off behind Yosh (Russell Westwood), Kristo's henchman, a POV shot as he drives his boss' open top car through the West End spreading word of the reward for finding Harry.

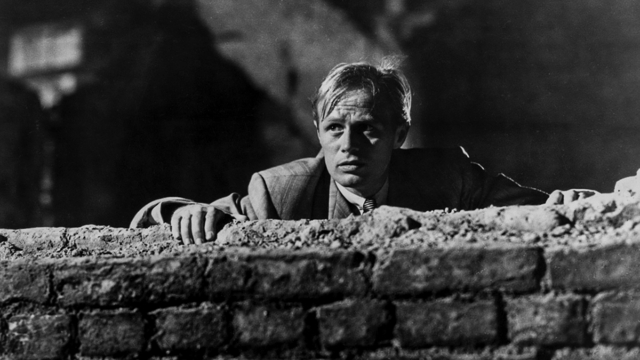

This kicks off the film's famous climax, as Harry is on the run again for his life through the darkened city. He runs through the docks and up endless stairs, past smokestacks and cranes, through bomb sites and building sites – scenes described as a journey through a labyrinth, which gives Dassin's film a mythic aspect that it earns.

Writing about the film in Somewhere in the Night: Film Noir and the American City, Nicholas Christopher says that "Dassin was dealing by necessity, not choice, with a European city; but in doing so, in the economically straitened postwar years, he presented that city as the antithesis of a great capital, the repository of a proud national culture. The London he gives us, crime-ridden and hardscrabble, is recovering from Hitler's bombardments and from years of terrible deprivation whose aftereffects have lingered deep in its collective nervous system."

Nicholas can't help but compare the film's protagonist with its director: "And was not Dassin at that point in time the very same thing: a director sharply attuned to the pulse of American city life who was unable to set foot in an American city. An artist without a country."

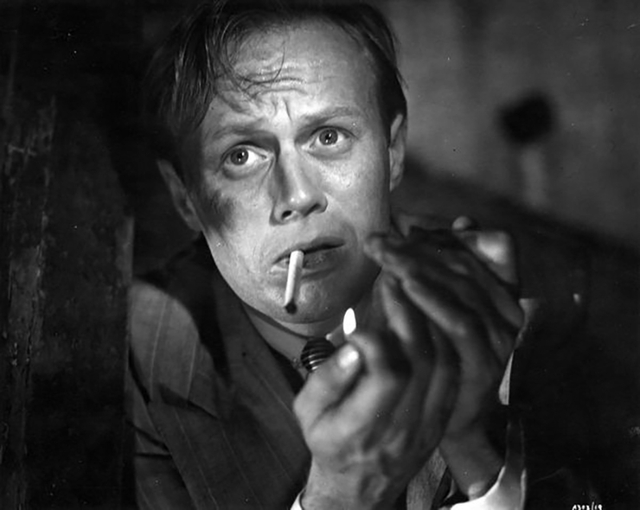

This would make sense if Widmark's Harry Fabian were more heroic, but he's not. Harry, Nicholas notes, "is a con man, and the con man's signature trait is his firm belief that he can con anyone, and in a pinch, maybe cheat fate for a little while. But the rub with Fabian is that because his abilities as a con man are so woefully meager he is able to hoodwink only a single person outside of himself: the film's oldest, most virtuous, and gullible character. With fate he hasn't a chance."

If you wanted to create a parallel between Harry and Dassin you'd have to agree that Dassin deserved the punishment he was enduring in exile, and I'm certain Nicholas doesn't believe this. Because Harry is an utter, irredeemable heel – a grifter lacking even the basic charm to get his grifts over, and our sympathy for him dries up utterly as we watch him frantically rifling through Mary's apartment looking for her money before shoving her aside when he finds it, though he does toss a few bills back at the sobbing young woman on the floor as he leaves.

Lom's Kristo, the film's conventional heavy, the spider at the centre of the city's criminal underworld, actually has more of a moral code than Harry. He's appalled that his father has been taken in by such a hopeless con man, and pledges he'll keep his word and allow Harry to pursue his doomed scheme but warns him: "Do not betray that wonderful old man."

Dassin put a lot of effort and screen time into the pursuit of Harry after his fall, going so far as to hire six cameras and their crew to leapfrog each other as they shot much of the denouement of the sequence in one morning by the river. "The London through which he scrambles and skitters" Nicholas writes, "is a labyrinth of grotesques, of smoke and vapor snaking from sewers, of wind-whipped construction sites and vacant lots in which huddled figures warm their hands over oil drums dancing with flames, of rotting wharves and docks congested with the flotsam of both the sea and the city; most of all , it is a city of endless doors and passageways, through any one of which, and through all of which, death aways Harry Fabian. His labyrinth is among the grimmest of film noir, for it is a maze in which every byway, and every possible combination of twists and turns, leads to his destruction."

And it is hard to deny that Harry deserves his fate, which puts the audience in the queasy position of – deep down in our gut – anticipating, even cheering on his destruction, which evokes similar ones in Brecht's The Threepenny Opera or Fritz Lang's M. The last half of the film is like watching a cruel, idle child pull a fly apart. It's truly tragic, in the ancient sense of the term, and not only because it is overseen by Kristos, a Greek, who, impassively and godlike, presides over Harry's destruction from the railing of Hammersmith Bridge.

And it's at the river, the Thames transformed into the Styx, where Harry has his final revelation, confessing to Anna the smuggler his sins and failings before Mary finds him. He tries one last time to run a scam that might pay her back for everything he's done to her before running headlong into his fate in the form of The Strangler.

Night and the City was a co-production between 20th Century Fox and British Lion, which saw two different versions of the picture released. The UK version has a different edit and, in some cases, wholly different scenes, and a soundtrack scored by Benjamin Frankel. The Fox version is five minutes shorter, with a score by Franz Waxman and portentous opening narration by Dassin. (Carol Reed spryly voiced the opening narration in the UK release.)

The bleak story wasn't appreciated much by critics at the time; Bosley Crowther of the New York Times described it as "a melange of maggoty episodes having to do with the devious endeavors of a cheap London night-club tout to corner the wrestling racket – an ambition in which he fails. And there is only one character in it for whom a decent, respectable person can give a hoot."

By the '60s it was re-evaluated along with much of the noir genre, praised as being seminal in its pitiless portrait of the doomed protagonist; definitely not a hero, and hardly even an anti-hero, Widmark's Harry Fabian occupies a role that resembles scapegoat more than anything else.

Irwin Winker (producer of Rocky, Raging Bull, Goodfellas and Round Midnight) directed a remake of the film in 1992, starring Robert De Niro and Jessica Lange and moving the story from London and wrestling to New York and boxing. Sadly for Gerald Kersh, the script had more to do with Dassin's picture than his nearly-forgotten novel.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.