The health of the American western in 1956 was robust if you go by just two pictures released that year: John Ford's The Searchers, probably one of the greatest westerns ever made, and George Stevens' Giant, which showed how western themes and values could be nudged forward into the modern world. It was also the year when Clayton Moore and Jay Silverheels transplanted the Lone Ranger and Tonto from television to the movie screen with The Lone Ranger – a hit for Warner Bros. and the first of two pictures featuring Moore as the masked gunman, proof that there was still an appetite for an old-fashioned oater, especially if you could fill theatres with ten-year-olds. (And thanks to the Baby Boom you could.)

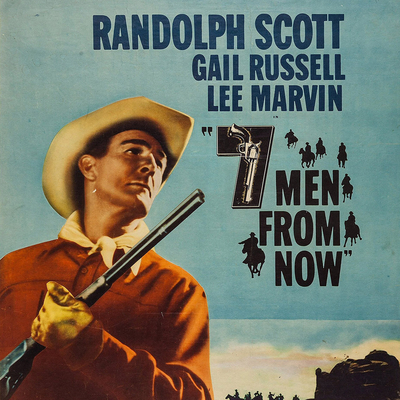

There was room for everyone and everything in the genre, and the year saw the release of another first – Randolph Scott's first film with director Budd Boetticher in what would become famous as the Ranown Cycle of westerns. Neither as epic as Giant or The Searchers or as cartoonish as The Lone Ranger, it would end up comprising "a series of westerns in which everything seemed to fit perfectly, nothing too loose and nothing too tight," in the words of critic Terrence Rafferty.

7 Men From Now – also known as Seven Men From Now depending on where you look – began as a script by Burt Kennedy, a US cavalry veteran who was decorated in the liberation of the Philippines. He studied acting when he returned home, while doing fencing training and stunt work while writing westerns for the radio. This led to a gig writing episodes for an unproduced TV western for John Wayne's Batjac productions, and finally the script for 7 Men From Now, which was supposed to star Wayne until his commitments to Ford and The Searchers led to Batjac offering the part of Ben Stride to Randolph Scott.

The film begins with a theme song by composer Henry Vars, a lusty bass and baritone male chorus singing about death and vengeance. Boetticher and Kennedy both hated the song, and hoped that it could have been cut by Batjac from future versions of the picture, but when the film was restored for a 2005 DVD reissue, Batjac and Paramount decided to keep it out of respect for the historical moment.

(They should have listened to Boetticher.)

After the credits roll we see Scott step into the frame from behind, walking in the dark through a thunderstorm to where two men are sheltering from the rain by a fire. He asks if he could impose on their hospitality with some warmth and a cup of coffee; one of the men is anxious, the other cool as they make small talk and then mention a killing during a Wells Fargo depot hold-up in a nearby town, at which point it's obvious that nobody is thinking about rain or coffee. Seven men escaped from the hold-up, though when the scene is over, we understand that it's down to five.

"Randolph Scott," as Rafferty wrote, "was born in the previous century. His hair was flecked with silver, his face was as craggy and crevassed as the landscapes he rode through, and his pale blue eyes looked as if they'd seen it all (and liked too little of it). The director, Budd Boetticher, a relative whippersnapper of forty, doesn't emphasize Scott's age, but he doesn't try to hide it either. The revenge-bent hero of this picture could be any age but young."

"Scott's Ben Stride," writes Robert Nott in The Films of Randolph Scott, "is not just a Westerner to respect and reckon with – as so many previous Scott heroes were – but a man to fear. Unlike the James Stewart character in the Anthony Mann Westerns of the era, Scott's Ben Stride is a man who hasn't quite gone over the edge yet. His fury and determination are still restrained, though like the Mann heroes, he's set on revenge and not too interested in letting anything stand in his way."

It would, of course, be a much shorter picture if nothing stood in Scott's way, and his first distraction comes with a couple whose wagon and horses have bogged down in the mud on the trail. John Greer (Walter Reed) and his wife Annie (Gail Russell) are a couple of easterners following Manifest Destiny west in search of a better life. They've run out of money and John has been forced to do odd jobs to get them all the way to California, where he intends to make a living as a salesman.

Stride – now with two horses, for obvious reasons – helps pull them free and takes pity on the couple, agreeing to accompany them along the trail to Flora Vista, the next town. Annie seems more stoic and capable than her husband, a garrulous man whose masculinity is derided by nearly everyone they meet along the way, and an attraction starts to grow between her and Stride.

This dynamic repeats itself in other films in the Ranown series; there's Karen Steele's Carrie and her absent-then-dead husband in Ride Lonesome (1959), and Maureen O'Sullivan's Doretta and her ambitious weasel of a husband in The Tall T (1957). These are women more worthy of the West and its challenges than their husbands and – by implication – more worthy of a man like Randolph Scott's loner hero.

The next obstacle is announced by a troop of US cavalry they encounter on the trail, who warn them that a marauding tribe of Chiricahua are in the area, and that they should turn back or head in another direction. Stride is already aware – they took his horse and ate it before the movie started, and he's skeptical of the cavalry officer's warning. Aren't half of the hundred or so Indians women and children, he asks, and aren't they starving?

7 Men From Now isn't an outlier in its sympathy for Native Americans in the latter stage of the settling of the West – every western I've reviewed for this column has been similarly partial to its First Nations characters when they appear, whether principal players or a looming menace in the background, to be fought despite their justifiable grievances.

The final obstacle arrives when Stride and the Greers have stopped at an empty stagecoach relay station to rest. Bill Masters (Lee Marvin) and his wingman Clete (Don "Red" Barry, the original Red Ryder) are also on the trail of the men who robbed the Wells Fargo depot, and Masters' plan is to follow in the wake of Stride as he finishes off the gang and take possession of the strong box and its $20,000 in gold that they took with them.

Marvin's Masters is the first of a series of estimable antagonists who appear in Boetticher's Ranown pictures, which include Richard Boone (The Tall T), Craig Stevens (Buchanan Rides Alone), James Coburn and Pernell Roberts (Ride Lonesome), and Claude Akins (Comanche Station).

"The Boetticher/Scott protagonist can be obsessive, monomaniacal," writes New York Times movie critic Glenn Kenny in an essay on the Ranown bad guys. "On the moral ladder, he sometimes stands only one or two rungs above the men he opposes. And the men he opposes, venal though they may be, almost always have their reasons. One of the neat tricks pulled off consistently by these movies is in giving us a western hero who fits within the parameters of genre convention without ever descending into cliché. Another is in putting him up against opponents who are just as intriguing."

It had been three years since Marvin had loudly emerged from the background of films with roles in The Big Heat and The Wild One, and he'd followed up on that promise with parts in The Caine Mutiny (1954), Bad Day at Black Rock and Pete Kelly's Blues (both 1955). He knew how to make a flamboyant, indelible impression, starting with his wardrobe for the picture; he sports a flowing purple scarf that was apparently his own addition, and on closer inspection what looks like a red bandana tied around his arm turns out to be a ruffled garter.

His Masters is a criminal – he's crossed paths with Stride before, when the vigilante was a sheriff and put him behind bars twice. But he has a code, and when he reacquaints himself with the former lawman he's at pains to point out that he doesn't kill innocent civilians. Masters is strictly there to profit from the misfortune of the men who made the mistake of inviting Stride's wrath since, as he informs the Greers while they wait at the relay station, the person killed during the Wells Fargo hold-up was Stride's wife.

When Annie tries to talk to Stride about the killing, he tells her that he was out of work after losing re-election for sheriff and had too much pride to take the job of deputy. He couldn't find another job and his wife had to take one with Wells Fargo; if he'd only been more humble she wouldn't have been in the way of the seven men who robbed the depot.

Masters is also smart enough to pick up on the attraction between Annie and Stride, and sets about flirting with her, belittling her husband, and goading Stride about becoming part of a budding triangle. He's an agent of chaos: a role that Marvin would come to play over and over, masterfully, across his career.

But Masters has every reason to want to keep Stride alive. When the newly enlarged group crossing the desert (the surreal landscape of the Alabama Hills outside Lone Pine, California – Boetticher's favorite location for most of the Ranown films) rescues a man being chased by Chiricahua warriors, Masters guns the man down when he tries to shoot Stride in the back, reducing the gang from five men to four.

"Marvin's cocky and perversely charming villain provides all the personality this picture needs," writes Rafferty, "leaving Scott to do what he does best, which is next to nothing."

Well, not quite nothing. There's a lovely scene during another nighttime downpour, where Scott's Stride crawls under the Greer's wagon for a bit of sleep after he assigns her husband to take a shift as sentry in case the Chiricahua come back. Russell's Annie is in the wagon above him, and they talk through the floorboards with an intimacy that belies the circumstances.

Gail Russell might be the most compelling heroine in the whole Ranown series. The actress had been picked for stardom at eighteen by Paramount, dubbed the "Hedy Lamarr of Santa Monica" and encouraged by her mother to pursue acting despite crippling shyness and stage fright. She would cry in her dressing room between takes, but was advised to take a stiff drink or two to overcome her awkwardness by the head of make-up on The Uninvited, a groundbreaking 1944 horror film directed by Lewis Allen.

Yvonne de Carlo said that Russell had been introduced to vodka by Helen Walker, another Paramount contract actress, and she would come to rely on alcohol for the rest of her career. In 1946 she was cast alongside John Wayne in Angel and the Badman; the actor took a liking to the troubled actress and had her cast with him again in Wake of the Red Witch (1948).

When Wayne's second wife Esperanza Baur was divorcing him she claimed that he'd had an affair with Russell while shooting the latter film, and though they both denied it and the allegation was rejected by the court, the scandal sent Russell's life out of control. Two weeks after the trial she was arrested for drunk driving; her marriage to actor Guy Madison ended in 1955 and the same year she rear-ended a car with a young couple and their baby, leaving the scene of the crime.

Russell was apparently cast in 7 Men From Now at Wayne's request, but there's nothing onscreen to suggest that his charity or her ongoing troubles affected her performance. She's an attractive woman – Marvin's Masters is constantly complimenting her on her beauty ("You move like you're all-over alive.") – whose intelligence shows in her face, but Boetticher and his crew had to handle her with care and caution.

In an interview with Robert Nott for his book about Scott, Boetticher described Russell as "a complete alcoholic."

"About two-thirds of the way through the picture, she was going to play a love scene where she was hanging clothes and talking to Randy, and she said 'Budd, I want to go back to the hotel, I'm not feeling very well.' And I knew she was going to go back and drink. I said, 'Gail, if you get in your car to head back to the hotel, I'm gonna pull you out of the car and spank you in front of the whole crew.' And she played the scene, and she was great. The night we got home from Lone Pine I had a big party at my house and she got drunk, and (assistant director) Andy McLaglen, who fell in love with her, couldn't find her for three days."

In 1957 she drove her convertible through the front window of Jan's Restaurant, a diner in Beverly Hills, pinning the janitor under her car. She failed to show up to court and was discovered passed out at home. She was fined, given a suspended sentence and three years' probation. Russell was found dead in the Brentwood home where she lived alone in August of 1961; she had drunk herself to death.

When Masters and Clete part ways with Stride and the Greers, he arrives in Flora Vista to find the last four men holed up in the saloon, where they'd agreed to meet John Greer after promising him $500 to smuggle the Wells Fargo strongbox and its gold across the trail. Back in the desert Greer confesses to the agreement, and Stride tells him to dump the strongbox on the ground in the middle of a canyon where he'll wait for the gunmen to come looking for their treasure.

But instead of heading straight for California, the Greers decide to head into Flora Vista to inform the sheriff – and tell the gunmen that he'd abandoned his end of the deal. He manages the latter but gets shot in the back by Bodeen (John Larch), the ringleader of the gang, while walking toward the sheriff's office, which prompts Masters to admit that Greer wasn't a half man after all.

There's a final showdown amidst the boulders and slanted rocks of the Alabama Hills where the wounded Stride has to face down not only Bodeen and his remaining men but Masters, who along with Clete saves Stride's life once again – before killing Clete and walking calmly to the final showdown with Stride.

We've seen Masters practice his fast draw repeatedly during the film (it was a favorite but of business for Marvin in several of his pictures) and assume the men are fairly matched, but when the end comes – Marvin executes a phenomenal staggering ballet after he's gut shot – Boetticher cuts away from Scott to watch Masters' shock when he's outdrawn by the older man before he can even touch his guns.

Like Charles Bronson's Harmonica in Once Upon a Time in the West, Stride is a supernaturally quick shot, even when wounded.

Boetticher's film made good money for Warner Bros. and Batjac and allowed him and Scott to go on and make the next five films in what would be known as the Ranown cycle – films that were hard to find on disc after the 2008 box set issued by Sony as The Budd Boetticher Collection went out of print, but have just been reissued on Blu-ray by Criterion.

John Wayne would regret turning down the part of Ben Stride, even if it was to play Ethan Edwards in The Searchers. And Boetticher's reputation, which very nearly disappeared Stateside by the '70s, would be nurtured and revived by European critics like André Bazin, who praised Scott's performance and the film simply: "Never a facial gesture, never the shadow of a thought or a feeling...No symbols, no philosophical backdrops, no psychological shading, nothing but ultra-conventional characters in totally familiar occupations."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.