The first glimpse I ever had of Robert Oppenheimer was in an episode of the landmark British television documentary series The World at War. (Soon to be the topic of this column.) It was in Episode 24 ("The Bomb"), which tells the story of the American nuclear program from its inception to the dropping of atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Oppenheimer does not play a huge part until they get to the first test of the "Gadget", on July 16, 1945 at the White Sands Proving Grounds, roughly midway between Albuquerque and El Paso. He appears, his face filling the screen, in footage from a 1965 NBC documentary called The Decision to Drop the Bomb.

It's a strange face, made stranger by the cameraman's decision to frame him in an unforgiving close-up that makes his long, pale face, with its big, wide-set eyes and prominent ears, appear like a goblin or an alien. It would have made an impression on me even if I didn't hear his voice, which sounded halting and haunted.

He remembers that some people in the room with him laughed, some cried, while he said he recalled a quote from the Bhagavad-Gita, the sacred Hindu scripture that he had apparently read in the original Sanskrit. (Or so I would learn later. This fact would comprise a large part of the myth of Oppenheimer.)

The deity Vishnu, part of a trinity that includes Brahma and Shiva, is trying to convince Prince Arjuna to fulfill his duty – his dharma, an expression of cosmic law and universal truth – and takes on his multi-armed form (often mistaken for the dreaded ten-armed form of the goddess Kali, though some translations describe it as having infinite eyes and mouths) to impress the prince, saying: "Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds."

"I suppose we all thought that, one way or another," Oppenheimer says, matter-of-factly, though there's no way of knowing if anyone else would express their reaction quite the same way.

In American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer – the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherman – it's never certain if this was, in fact, the thought at the forefront of Oppenheimer's mind. William Laurence, a New York Times reporter on the scene at the Trinity Test quoted him saying that it was "terrifying" and "not entirely undepressing," adding that "lots of boys not grown up yet will owe their life to it."

The quote didn't show up in the book Laurence published in 1947, but it did appear in a 1948 Time magazine story, and in a 1958 history by Robert Jungk, Brighter Than a Thousand Suns, before Laurence would finally use it in his 1959 book Men and Atoms. Physicist Abraham Pais, a friend of Oppenheimer's, would speculate that it sounded like one of the scientist's "priestly exaggerations."

In choosing to make Robert Oppenheimer the focus of his film, director Christopher Nolan has made sure that Oppenheimer will give audiences an overdue look at the fascinating character of the man who acted as midwife to the atomic age, while ensuring that their understanding of the political and ethical debates over the invention and deployment of the Bomb will be no clearer.

There have been movies about the first nuclear weapons before. Fat Man and Little Boy (1989) focused on Paul Newman's Gen. Leslie Groves, the military leader of the Manhattan Project, while Hiroshima (1995), a Japanese-Canadian co-production, centered on US president Harry S. Truman's role in the decision to drop the bombs.

Hume Cronyn was well cast as Oppenheimer in the nearly-forgotten The Beginning or the End (1947) though the story focused on two fictional characters – a scientist played by Tom Drake and a military observer played by Robert Walker – while there have been two movies about Col. Paul Tibbets and the B-29 crew who dropped the bomb on Hiroshima: Above and Beyond (1952) with Robert Taylor as Tibbets and Enola Gay: The Men, the Mission and the Atomic Bomb (1980), a TV movie starring Patrick Duffy, Kim Darby and Billy Crystal.

What this suggests is that the story of the Manhattan Project and the conflicts and controversies crucial to the invention of nuclear weapons is so vast that it needs to drill down on one or two individuals with a stake in the historical moment to fit it into a reasonable ninety minute or two-hour movie. (Or even a less reasonable three-hour one.)

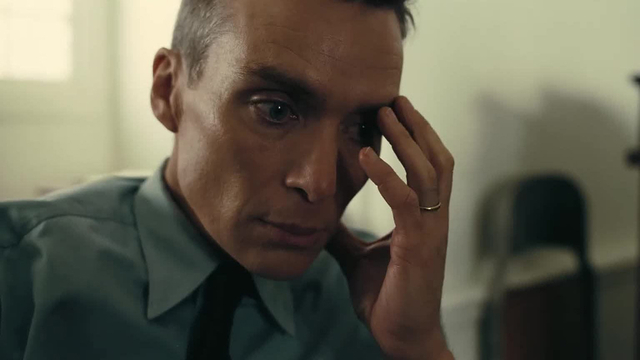

Basing the story around Oppenheimer means a filmmaker has opted for the much more ambitious and ambiguous take, and it's no surprise that Christopher Nolan (The Dark Knight, Inception, Tenet, Memento) would choose this option. You could argue that the Oppenheimer version had to wait for someone like Nolan to occupy a position of privilege in Hollywood, and serendipity enhanced the moment by allowing him to cast Cillian Murphy as Oppenheimer.

Robert Oppenheimer was a peculiar man, and very far from the conventional hero of any story, even one that requires at least a vague familiarity with the quasi-mystical concepts of quantum physics. Gifted with both privilege and genius, Oppenheimer is consistently described in Bird and Sherwin's book as charming and otherworldly – an intellectual with an earthy aspect that neatly overlapped with his apparently immense appeal to women.

Murphy, the best physical match for Oppenheimer since Cronyn, lost weight for the role to evoke the scientist's ethereal appearance, and he dominates the screen in the company of an all-star cast. There's Matt Damon as Groves, his foil and protector, Tom Conti as Einstein in three brief but crucial scenes, and Emily Blunt as his wife Kitty – an intelligent and capable woman who'd have enough to deal with as the "great man's wife" even without his incessant affairs.

The only time Murphy very nearly gets overshadowed is Gary Oldman's cameo-length appearance as Truman, who swiftly but decisively reminds Oppenheimer and the audience that the scientist was not the only star in the story of the Atomic Bomb troubled by his role.

The key drama in the story of Robert Oppenheimer is, of course, the race to beat Nazi Germany to a practical nuclear weapon, and the Manhattan Project is the core of Oppenheimer. But this is a Christopher Nolan picture, and that story is woven deeply into a movie built on Nolan's trademark temporal gymnastics – flashing back and forward and back again over and over.

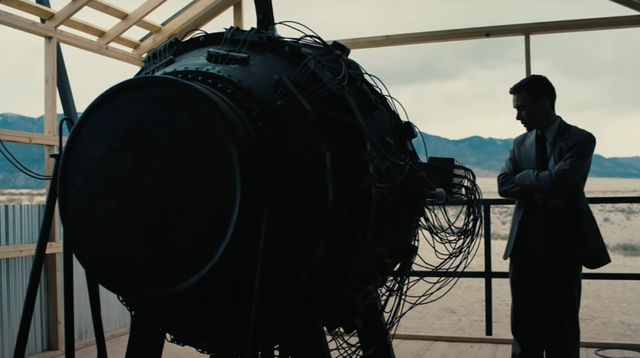

Los Alamos and Trinity only comprise about a third of American Prometheus, the source of most of the material for Nolan's script, and so the Manhattan Project is less than half the movie. It's also the most exciting part; the struggle to overcome the head start by Werner Heisenberg and the German scientists – presumed to be two years – and basically invent a whole branch of science out of mostly theory is one of the great achievements of the last century, no matter what you think of the result.

We see Oppenheimer transform himself from the classic absentminded professor, a dilettante whose restless mind kept him from dominating a single idea or innovation (he would never win a Nobel prize, but his team on the Manhattan Project was loaded with Nobel laureates), into that rare thing – a creative bureaucrat, delegating and inspiring thousands of workers, many of whom had egos to match his own.

He was nowhere near the "inventor" of the Atomic Bomb, though that was the title he would be given later, but he was the genius who was able to oversee hundreds of geniuses and make them deliver very nearly on schedule. It helped, of course, that he was funded by the wealthiest government on the planet, to a final total of $2.2 billion.

(I'll let you figure out what that means today, adjusted for inflation. It's ... a lot.)

But when the countdown ends at the climactic moment, we see the explosion largely at a distance – a fire-filled mushroom cloud miles away, against a dark sky. It makes sense, of course – this is how the witnesses at White Sands that day would have seen it, at a safe distance, and not looming and overhead like the bomb's intended victims. There is a lot of talk – in the movie, back then, nowadays and every year in between – about the morality of using the bomb on a city, but you can't help but wonder if the people who made it and the people who chose its targets were influenced by seeing it at a distance.

But you'd probably have to ask someone who was there, and there are no living witnesses to the Trinity Test today.

The balance of the film comprises the young Oppenheimer – an anxious and depressed young genius in search of his milieu – and the fall of the post-Trinity Oppenheimer at the 1954 security hearing depicted in the film as a Star Chamber show trial where the scientist, still at the peak of his reputation, is denied his official government security clearance, effectively ending his career as a practical scientist. This is woven with a 1958 Senate confirmation hearing where the man who covertly orchestrated Oppenheimer's disgrace, former Atomic Energy Commission chairman Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), reaps his karmic whirlwind.

You might assume that the villain in a film about Robert Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project would be his opposite number, Heisenberg, and the Nazi atomic weapon program. But Hitler was dead and Germany defeated before the Trinity detonation, and after the war the Allies learned that Heisenberg had made crucial mistakes in his research (on purpose, he would later insist) and the program had been underfunded and out of favour with Hitler in any case.

So the real villain of Oppenheimer is Downey's Strauss, an American – aided and abetted by Kenneth Nichols (Dane DeHaan), a US Army civil engineer depicted by Nolan as Groves' assistant (a gross oversimplification of Nichols' actual role), a disgruntled member of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy named William Borden (David Dastmalchian) with a grudge against Oppenheimer, and Roger Robb (Jason Clarke), the lawyer representing the AEC at the 1954 hearing.

Downey plays Strauss as the model civil servant – a self-made man with an avid interest in physics who felt snubbed by the high-handed Oppenheimer when he recruited him to be the director of Princeton's Institute for Advanced Study, and humiliated by the scientist when he glibly ridiculed Strauss at a 1949 public hearing on the export of isotopes.

In American Prometheus Strauss is described as "pathologically ambitious, tenacious and extraordinarily prickly, a combination that made him a particularly dangerous opponent in bureaucratic warfare." One of his colleagues at the AEC said that "If you disagree with Lewis about anything, he assumes you're just a fool at first. But if you go on disagreeing with him, he concludes you must be a traitor."

Since Oppenheimer isn't a fool, Strauss goes straight to traitor; for the purposes of the film he's a small man made uncomfortable by genius, so he schemes and enlists other small men to take the giant down, using the one thing that Oppenheimer made obvious and available to anyone who needed damning evidence after the war – his political sympathies and those of his friends.

Then as now, academic scientists lean left, and Damon's Groves struggles to recruit scientists to the Manhattan Project that can pass the security clearance – Oppenheimer more than most. Like many of his faculty peers and students, he'd backed the Popular Front during the Spanish Civil War, and by his own admission ended up supporting nearly every Communist Party front group in California.

That he was never a party member meant nothing to the members of the 1954 hearing; that there would have been far fewer scientists building the bomb at Los Alamos if postwar security guidelines had been in force is basic history. Oppenheimer himself retreated from his leftist sympathies as soon as he saw a chance to get involved with the Manhattan Project. What he couldn't do – and many people might make the same choice – was disavow his friends and family.

Cillian Murphy does a great job portraying the Oppenheimer presented in Bird and Sherwin's book – an awkward man who does a wildly convincing impersonation of grace. The depressed and troubled young man who nearly poisoned his Cambridge physics tutor with a drugged apple (an incident wildly misrepresented by Nolan's creative license in the film) managed to find some equilibrium in the brand-new field of theoretical physics, combining it with his taste for eastern mysticism to create a worldview that provided something like emotional stability.

An academic colleague of Oppenheimer who met him after marrying an old school friend said that something about his manner "made people fall in love with him – male, female. Almost everybody." But he added that "the more intimately I was acquainted with him, the less I knew about him." This combination of immense charm and unknowable mystery made him honeydew for women, and Oppenheimer's personal life would become a tangle of flirtations and affairs.

But in Nolan's film the point where his messy love life and his political sympathies combine to create his Achilles heel is his affair with Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh), the daughter of a Berkeley Chaucer scholar. It was Tatlock's love of John Donne's poetry that inspired him to name the Trinity Test, referencing Donne's sonnet about a "three-person'd God." A brilliant and intense young woman studying to be a psychologist, she was also a card-carrying Party member who confided to a friend that "I just wouldn't want to go on living if I didn't believe that in Russia everything is better."

(She died of suicide, under suspicious circumstances, in 1944.)

She was, in all likelihood, the love of Oppenheimer's life – a woman who threw out the flowers he would bring her and turned down his marriage proposals twice. His devotion to her damages his marriage and puts him deeper on an FBI watchlist. In Nolan's film she's the archetypical bad girlfriend – the one who picks fights with strangers that you have to finish, and makes you drive her home halfway through a weekend with your family.

It's Pugh's Tatlock who features in the film's love scenes – because even a film about Robert Oppenheimer must have nudity. In the first of them she idly pulls a book in Sanskrit off the shelf in his bedroom and challenges him to read it aloud to her. Murphy tries to give a general description but she insists he recite an exact translation. It's a passage where Vishnu confronts Prince Arjuna, and while Pugh straddles him, holding the book open in front of his face, he reads aloud:

"Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds."

It's the first time we hear the words in the movie. I imagine it'll give a new generation a fresh take on the words I couldn't have imagined while watching The World at War fifty years ago.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.