When you have a job like this, there are films you slip into like a warm bath, and others that you take like bitter medicine. My dear friend Kathy Shaidle, writing here exactly four years and one month ago, admitted that she was reviewing Satyajit Ray's Pather Panchali (1955) not out of real interest but a sense of obligation.

"I first watched Pather Panchali on TCM last May, merely to discharge a 'see before you die' duty," Kathy wrote. (This would be five months before her cancer diagnosis. I doubt the irony would escape her; no irony, no matter how small, ever did.)

"This film – with its unpronounceable title and director, its nobody cast and beyond-foreign, unglamorous milieu – had been sandwiched between Citizen Kane and The Rules of the Game on every 'great movies' list I'd ever seen. So damnitall, I was gonna sit through it, however penitentially."

This was one of my favorite columns by Kathy, and when I took over this space I knew what my Pather Panchali would be, in the form of a filmmaker whose work had fascinated me for years, while repelling me with every feint I made at actually sitting through a whole movie.

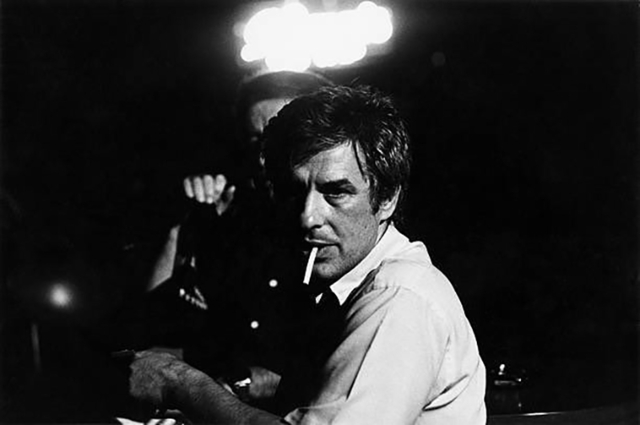

Photograph by Sam Shaw |

Like most people, I knew John Cassavetes as an actor, in films like Rosemary's Baby and The Dirty Dozen, and on TV shows like Combat!, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea and Colombo. It's evidence of how sketchy my youthful knowledge of film really was that I was stunned when I realized that he was the same man as the director of all these very adult, art house films that critics constantly talked about – movies like A Woman Under the Influence, Opening Night and Love Streams.

Movies, I'm at pains to point out, that I never saw. Because even though they were films critics talked about, they didn't often have anything nice to say about them. Pauline Kael called Faces (1968) "dumb, crudely conceived, and badly performed." "Muddle-headed, pretentious, and interminable," was what John Simon had to say about A Woman Under the Influence (1974), while Stanley Kauffman called it "utterly without interest or merit."

With those sorts of recommendations, it's a challenge to know where to begin, so I took the advice of a friend who loves Cassavetes and picked a film that almost everybody hated when it came out. Why make things easy on yourself?

Cassavetes made The Killing of a Chinese Bookie in 1976, just two years after A Woman Under the Influence, which got him an Oscar nomination for best director, in spite of what the critics had to say. (His wife, Gena Rowlands, would also be nominated for best actress, and would win a Golden Globe for her role as a working-class mother losing her mind.)

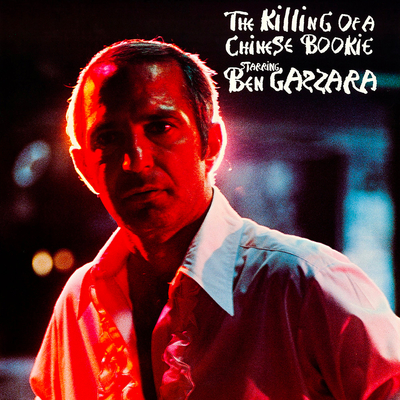

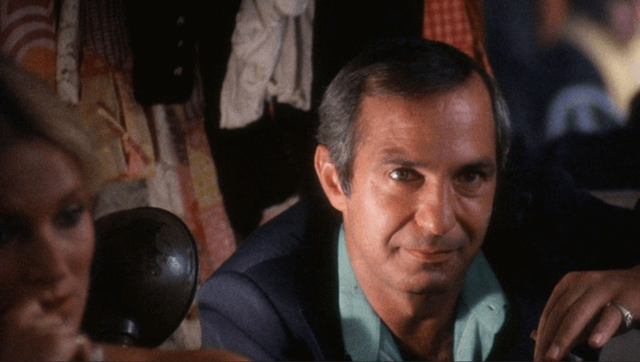

Ben Gazzara, returning to Cassavetes after starring in Husbands (1970) alongside the director and Peter Falk, plays Cosmo Vitelli, the owner of a bar on L.A.'s Sunset Strip. Cosmo runs the Crazy Horse West as something between a burlesque house and a cabaret, with shows and sets that he writes and designs himself, emceed by the comically pathetic Mr. Sophistication (Meade Roberts). Cosmo is also a degenerate gambler, and the opening scenes feature him paying down a gambling debt he owes to the gangster Marty (Al Ruban, also the film's producer and one of its cinematographers).

Free of his debt, Cosmo decides to celebrate, and invites three of the club's dancers out for a night on the town – one of whom, Rachel (Azizi Johari), is his erstwhile girlfriend. Cosmo rents a limo and buys corsages and shows up to pick up the girls at their homes – the scene plays like he's taking them to prom – but by the next morning the women have been sitting around while watching Cosmo lose $23,000 at another mob-run poker game.

There's a great scene where the four of them wait around for Cosmo to negotiate with the mobsters who run the place, including the slick Mort (Seymour Cassel, another Cassavetes regular) and the uncouth and violent Flo (Timothy Carey, an indelible character actor audiences will know from Ace in the Hole, The Killing and Paths of Glory). We see them leverage favours from other gamblers, including the anxious wife of an outraged urologist, though they only ask Cosmo to sign a couple of helpfully numbered forms.

As Ray Carney wrote in Cassavetes on Cassavetes, a biography of the director comprised largely of quotes from interviews, the man could be an unreliable narrator, an observation that's borne out by watching just one of his films: "There were times when my sources contradicted each other, and many times when Cassavetes directly contradicted himself. Perhaps some truths are forever irrecoverable, lost in the dark, backward abysm of time."

Cassavetes said that the idea for the film began when he noticed all the clubs that once dotted the Sunset Strip with variations on the come-on of "live nude girls," and decided to go inside, interviewing the owner of one place who inspired the character of Cosmo. Carney writes that he was inspired by nights he spent at Le Crazy Horse, the (in)famous cabaret in Paris, and particularly its flamboyant owner, Alain Bernardin, who also designed and choreographed his shows.

Another story has the film begin as an idea Cassavetes tossed around with Martin Scorsese and producer Sam Shaw; there have been rumours that Cassavetes originally intended for Scorsese to direct it, but he insisted that was never true, and in any case Scorsese was working on Taxi Driver at the time, which was released within a few days of Cassavetes' film. (They would make a great double bill.)

For the Crazy Horse West, Cassavetes filmed at Gazzari's, one of the Sunset Strip's most venerable clubs, adding a false front and a stage to transform the place. He got into an argument with Ruban, however, when the cinematographer tried to light Cosmo's show to the best of his abilities, while Cassavetes insisted on garish coloured gels and hard lighting. Ruban tried to quit, but Cassavetes talked him into staying to shoot the film's exteriors, while two other cinematographers worked on the film and the director himself wielded a handheld camera.

He got actual strippers to play the club's dancers. Azizi Johari had been Playboy's Playmate of the Month in June of 1975, while another dancer was played by Haji – real name Barbarella Catton, a Quebec-born Russ Meyer regular who incorporated magic tricks into her act as an exotic dancer. David Bowie was hanging around the set during filming and can apparently be glimpsed in the crowd at the club, but I haven't been able to pick him out.

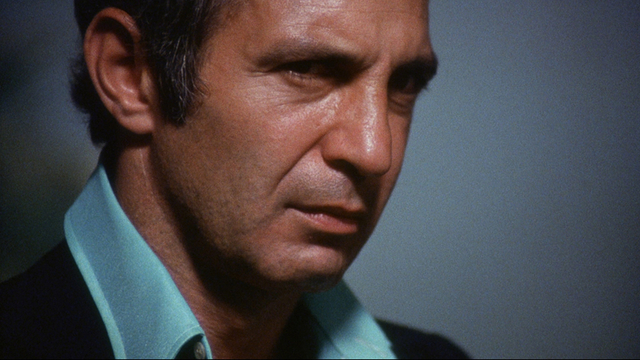

Carney writes that the director based Cosmo on both Gazzara's personality, and his own: "Gazzara was similar to Cosmo in many deep and half-veiled respects - most notably in his devotion to living a life of 'style' and 'class' and his interest in 'looking good' and being the center of attention in a group. Cassavetes was fascinated with this aspect of Gazzara's personality because he shared some of its qualities, including the love of costumes, corsages and limos."

But Gazzara had a hard time focusing on Cosmo, and complained that the shoot wasn't as much fun as the one for Husbands. But at the end of the scene where Cosmo drops the girls off at home after the night at the casino, Cassavetes – who was sitting on the floor of the limo in front of him with his handheld camera – tearfully tried to explain the character and the film to the actor.

"Ben, do you know who those gangsters are? They're all those people who keep you and me from our dreams. The Suits who stop the artist from doing what he wants to do. The petty people who eat at you. you just want to be left along with your art. And then there's all the bullshit that comes in, all these nuisances. Why does it have to be like that?"

Cassavetes invited numerous Hollywood hot shot producers and executives to play extras in a scene where the gangsters meet at Carmine's Italian Steakhouse on Santa Monica Boulevard, and then spitefully cut their faces out of the finished scene. He enjoyed shooting that scene so much that he exposed 80,000 feet – fourteen hours – of footage for a sequence that he knew would only last a few minutes in the film.

A cursory description of the film – Cosmo is given the chance to cancel his debt to the gangsters by killing a bookie that's been giving them trouble, who turns out to be a Triad boss with a small army's worth of security – makes it sound like a gangster picture, the sort of mob movie that had become popular since the success of The Godfather. And Cassavetes himself mused that he would have loved to have directed a genre picture – particularly one that would have made him a lot of money – but that he simply wasn't capable.

"People love form," he said. "In films, they love genre. Is it a comedy, an epic, a thriller? There doesn't seem to be anything in between. I'm no different. I go to a film sometimes, 'Oh, God! I don't want to see a Bergman film tonight! I'll watch a gangster film.' I would have liked to have made more commercial films, closely knit, not confusing, where there is an answer for everything and it's all greatly entertaining. But I started to make films and none of that came out. Instead this expression of dissatisfaction with the tightness of the form kept emerging."

What Cassavetes loved to show – and what drove critics and audiences crazy – were delays; pauses in the action and pace where characters deliberate and doubt what they're supposed to be doing. The best example in The Killing of a Chinese Bookie is when Cosmo, on his way to do the killing with a gun and a stolen car given to him by the gangsters, has a tire blow out on the freeway.

Instead of forging ahead or calling in a favour, he goes to a telephone booth and calls the club to find out how the show is going that night – a near-comic routine that plays like demented Bob Newhart standup. Waiting in a bar after he orders a dozen burgers to feed to the bookie's dogs to distract them, he gets into an argument with a waitress who's worried why he didn't order the burgers individually wrapped, the bartender intervening to keep everyone's temper in check.

These agonizing pauses in the film's "action" came from the director's apparent unwillingness to shoot the scene that was promised in the title of his own film. "Cassavetes sat in Hamburger Hamlet with his actors and crew from 6 p.m. to midnight on the appointed evening," Carney writes, "debating whether he should actually go through with it, soliciting their opinions: 'Do you think he really would do it?' 'Do we have to shoot him?' 'Why?' 'What if we don't shoot the Chinaman?'"

What Cassavetes hated – and he wasn't wrong – was how characters in films often betray their backstories and characterization by simply being where and doing what the story requires them to be and do, to satisfy genre conventions or the needs of a weak script. This describes almost all television and the vast majority of movies, good or bad. We accept it because we want to be entertained, but Cassavetes resisted the temptation with results that are maddening, and which confounded both critics and audiences.

It made it impossible for him to enjoy most films, even those made by his most talented peers. "The problem with Apocalypse Now," Cassavetes said, "is that Sheen and Duvall didn't find any truth in their roles. They couldn't justify them. You have to do that. If only Sheen had inserted some delays, he might have saved that script. Phoniness doesn't interest me. There are lots of phonies in the movies, an actor playing a part. Nobody is a phony like that! I'm interested in how people fool themselves, not how they fool others."

"I always feel left out of most movies," he said. "They have nothing to do with me. I don't particularly like movies. I'm not really fascinated by them. They're usually a double-cross...People don't know what they are doing most of the time, myself included. They don't know what they want or feel. It's only in the movies that they know what their problems are and have game plans for dealing with them. Why should we have to be the way people aren't? Life is stranger than the movies."

Which is why, by the time Cassavetes gave himself a reason to actually film the gangster picture he'd set out to make, he'd lost interest in the story of a man forced to commit murder to save himself and his livelihood – the sort of dark moral fable that any half-decent film noir would happily set about.

"I hate entertainment," Cassavetes said. "There's nothing I despise more than being entertained."

Cassavetes was known as an actor's director, but he considered what he did as an antidote to Method Acting, and loved casting non-actors in his films, certain that their lack of artifice helped real actors avoid theatrical ritual and find something truthful in their performances. When it worked, it was magic, but when it didn't work – and it often didn't – it just added to all the things that drove audiences and critics into resentful rages, pitching his already unconventional stories onto an uncomfortable knife's edge.

Which is why, after dispensing with the actual killing the movie's title promised, Cassavetes seems to become interested in his story again. Wounded in the shoot-out with the Triad leader's guards, he struggles to get to the home Rachel shares with her mother, Betty (Virginia Carrington).

Cosmo calls Betty "Mom" and wants their home to be a refuge for him, but Betty knows that what he's done has brought on a lot of trouble for him – and them – and kicks him out. It's an awkward, painful scene as played by the very actorly Gazzara and the non-professional Carrington, with Gazzara raging and emoting heavily against Carrington's passive, unhysterical performance, but we've seen it played out with conventional movie dynamics so many times before; in Cassavetes' film Cosmo's banishment has a finality that feels palpably catastrophic.

Cosmo ends up back at the club, where the show is late starting and he's moved to give his troupe a pep talk after Mr. Sophistication confronts him with complaints that he feels underappreciated – a butt of jokes, and the easy target of audience abuse when the show doesn't go well. He admits that there's something "freakish" about his onstage persona.

Meade Roberts was another non-actor – a screenwriter who had worked with Tennessee Williams on The Fugitive Kind (1960) and Summer and Smoke (1961), and wrote The Stripper (1963), which starred Joanne Woodward as the tragic title heroine. He'd had a great career until the '60s, but he was a has-been by the time Cassavetes cast him as Cosmo's onstage doppelganger.

"He's a very dear friend of mine," Cassavetes said, "but he's had a lot of problems...In Bookie, he insisted on me putting make-up on him, though I never normally use make-up. We used to talk and have a good laugh as I was making up his face. We started fantasizing about the character he played. He said, 'Who is he?' I answered, 'Well, he's a high-school teacher. But he was not happy with his relationship with his students and not happy about his life either. He is very cultured, but he doesn't know what to do with it. He enjoys singing, and he meets this nightclub-owner who has no culture, but who has a big heart and wants to do everything himself. And this guy Cosmo discovers that he can do himself a favor by giving this man something to feel good about himself – so he hires him.'"

Sitting in the dressing room, Cassavetes lets the scene play out between the dancers and the emcee and the club owner and his musical director, and Cosmo rallies his troops:

"Let's go down there and we'll do a great show. We'll smile, we'll cry big glistening tears that pour onto the stage. So they won't have to face themselves. They can pretend to be somebody else."

It sounds like a celebration of artifice and entertainment that goes against everything that Cassavetes protested he hated, but maybe that's just another reason why it infuriated audiences. All I know is that when Cosmo was standing outside his club on Sunset wiping the blood from the reopened gunshot wound on his coat, I felt like I'd spent so much time in the world Cassavetes had created for him that I needed a shower.

The film did not do well. Like Cosmo, Cassavetes took a big gamble on Bookie opening big – he printed up thousands of high-quality press kits and ordered hundreds of prints of the film to be struck. He rented offices in L.A. and New York and hired staff to publicize the picture, but he put less effort into editing, delegating that work and ending up with a 135-minute cut that bombed.

"Only two or three critics in America liked the film," Cassavetes recalled. "Every other one attacked it. My films live or die by what the critics say because the audiences who see our films are influenced by critics. So when the reviews came out I said we should close. I didn't know how we could fight a unanimous blast. We only played five or six theatres in all, and it did not do well at any of them. Audiences generally disliked the film and didn't want to see it. Pauline Kael has never given me a good review, but I have a dream that she is going to not go along with the crowd and like Chinese Bookie."

Kael ignored the film, but the L.A. Times Sunday magazine did run a 1,700-word piece discussing how much audiences hated the picture. Cassavetes pulled it from the theatres but went back and edited it again for a 108-minute re-release in 1978 that cut out a lot of the club scenes. That also bombed.

(I lied at the beginning of this column when I said that I don't like to make things easy on myself. Given a choice of the two edits that come with the Criterion reissue of the film, I went for the shorter one.)

After telling his wife that he couldn't work with her again after the stress of making A Woman Under the Influence, Cassavetes' next film was Opening Night (1977), starring Rowlands as an actress having a breakdown while doing out of town tryouts for a play. This was followed by Gloria (1980), another gangster picture, with Rowlands as the only truly heroic protagonist in any of his pictures.

Love Streams (1984), also with Rowlands, was better received, but his final film would be a terrible compromise. Peter Falk had asked if Cassavetes could take over Big Trouble (1986) after writer/director Andrew Bergman was fired with less than half of the film finished. He worked on it for year trying to save the movie but like nearly everyone else regarded it as disaster. A lifelong alcoholic, Cassavetes died of cirrhosis of the liver in 1989.

His critical reputation has grown considerably since his death, and all of his children have found careers in movies. Director Brett Ratner bought the rights to The Killing of a Chinese Bookie in the '90s and had Cassavetes' son Nick write a screenplay but thank God that never got made.

Like almost anyone whose reputation grew immensely after their death, you have to wonder if Cassavetes would consider it a consolation, considering all the turmoil and stress and calumny he lived through while making his pictures. I suspect he would have traded a few retrospectives and deluxe Blu-ray reissues for at least one undeniable hit. But maybe he wouldn't. As he described his relationship to the movies:

"I don't know – somehow I got hooked. I got hooked on movies being an expression. A substitute for living! And a good one. I don't how to live. I mean, I don't know how to dress or get on with people. I don't even understand all that stuff. It drives me crazy."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.