The department store will probably disappear in the next ten to twenty years, according to everyone who still cares about department stores. Writing in the early months of the pandemic, the New York Times predicted that lockdowns would deal the killing blow. If they didn't disappear outright, "there is expected to be an enormous reduction in the number of stores in each chain, which once sprawled across the American continent like a pack of many-headed hydras."

That sort of bleak language – "many-headed hydras" sprawling across a continent – paints a bitter picture of an institution that was once a retail innovation, a game-changing business model as economically crucial as online shopping, fulfillment centres, same-day delivery and instant downloads are today. More than that the department store was, not so long ago, a setting in movies as common and vital as today's cubicle farm or pretentious coffee shop.

By the middle of the last century the department store as shopping destination and workplace was ubiquitous, in films like Miracle on 34th Street, The Big Store, Holiday Affair, Modern Times, Safety Last!, You and Me, There Goes My Heart, The Jackpot, Our Blushing Brides, Employees' Entrance, Bachelor Mother, Who's Minding the Store?, One Touch of Venus, Every Girl Should be Married and many more, if you're just counting Hollywood films.

Strange as it sounds today, as the empty husks of department stores sit at the withered extremities of shopping malls everywhere, the department store was once regarded as not just modern and aspirational, but stood as a microcosm for society as a whole in movies – populous but stratified along class lines, from the budget shoe department in the basement to the perfume counters by the main entrance to the competitively elegant upper floors selling furs and designer dresses.

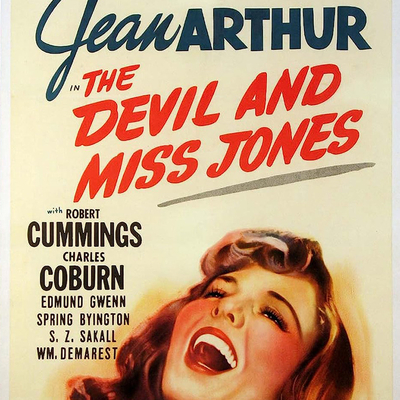

I worked in one of these retail palaces, the flagship downtown store of one of Canada's two department store empires, bouncing haphazardly from the employees' cafeteria to accounting to the toy department, punching a clock at the beginning and end of every shift. More than any other place where I drew a wage, Simpson's Queen Street felt like I was living in a movie set, and every time I watch a film like The Devil and Miss Jones (1941) that's set in a department store, I can almost smell the old building again.

The film begins with a tongue-in-cheek note after the title credits:

Dear Richest Men in the World:

We made up this character in the story, out of our own heads. It's nobody, really. The whole thing is make-believe. We'd feel awful if anyone was offended.

Thank you,

The Author, Director & Producer

P.S. Nobody sue.

P.P.S. Please

It's a coy little come-on, inviting us to imagine just what plutocrat the film is going to satirize. John D. Rockefeller? Howard Hughes? John Paul Getty? Michael J. Cullen, the now-forgotten inventor of the supermarket? We know we're in the realm of the truly wealthy with the opening shots – a procession of chauffeur-driven black cars pulling up to a Fifth Avenue address, discharging a quartet of stony-faced men in homburg hats who proceed silently through the marble and gilded iron foyer of some Upper East Side mansion, each of whom could be the tycoon the apology is supposed to mollify.

They are, in fact, all in attendance to one man, their boss, John P. Merrick – Charles Coburn, in the role of the same gruff millionaire he'd play with variations in Bachelor Mother (1939), Road to Singapore (1940), H.M. Pulham, Esq. (1941), In This Our Life (1942), The More the Merrier (1943), The Constant Nymph (1943), Heaven Can Wait (1943), Monkey Business (1952), Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) and How to Murder a Rich Uncle (1957).

Merrick is an anhedonic millionaire who lives alone in the echoing mansion and subsists on graham crackers soaked in milk served by his butler, played by the reliably charming S.Z. "Cuddles" Sakall. He also abhors publicity, and has gotten more than he wants after a group of disgruntled employees at Neely's, a Manhattan department store, have hung him in effigy during a protest. At first he's baffled – he wasn't aware that he even owned a department store: "I thought I sold everything below 38th Street years ago."

This throwaway line is telling, and hints that the decline of the department store has been going on much longer than we think. Lord & Taylor and Franklin Simon & Co. were both on 38th at Fifth Avenue; below that was B. Altman, A&S, Macy's, Arnold Constable, Alexander's, Wanamaker's, Gimbels and discount department stores like Mays and Ohrbachs. Above that were luxury stores like Bonwit Teller, Henri Bendel, De Pinna and Bergdorf Goodman.

Thirty-Eighth Street was an informal dividing line between the mass-market and discount retailers and the older stores that didn't move from the old Ladies' Mile by Madison Square, and the more prestigious upscale department stores, and would close or get bought out starting in the '60s and '70s. Merrick along with other savvy investors saw how the blue-chip stores offered potentially higher profit margins, but Neely's survived in his portfolio thanks to being on the right side of 38th.

Coburn's Merrick is a far nastier chief executive than, for instance, his pragmatic plutocrat in The More the Merrier, or Walter Connolly's in Libeled Lady (1936) and Fifth Avenue Girl (1939). He tells his flunkies to fire everyone in the photo, but they reply that they've prudently hired a private detective to take a job at the store and winnow out the troublemakers. Merrick decides that he'll take on the job himself, and anticipates that he'll do a much better job of it thanks to his superior intellect, calling his querulous workers "morons...sheep. No wonder you can convince them of anything."

Merrick arrives at the store in his undercover disguise as Higgins, but thanks to the low score the private detective made on the store's intelligence test, Hooper the floor supervisor (Edmund Gwenn) assigns him to the slipper counter – apparently the bottom of the barrel in the department. He's taken under the wing of Mary Jones (Jean Arthur), the hard-working moral center of the shoe section, who takes pity on the obstreperous but befuddled old man who refuses to take a lunch break because he lacked fifty cents for a meal in the employees' cafeteria.

Mary is also the point man for union organizing at the store after her boyfriend Joe (Robert Cummings) was fired after the protest. She unwittingly takes Merrick along to a meeting on the rooftop of her apartment building, and even makes a speech that portrays him as a pathetic figure – an old man with no money or prospects who'll likely be fired as soon as he's been at Neely's long enough to earn a few raises, to be replaced by younger, cheaper hires.

(Merrick/Higgins is, we're told, 55 years old; Coburn was 64 when he made the picture. It's purely anecdotal, but it's hard not to take this as evidence that people used to either age much quicker or embrace looking older more sedately.)

The Devil and Miss Jones was made by an independent production company set up by Arthur and her husband, producer Frank Ross, to provide an escape from her hated contract with Harry Cohn and Columbia Pictures. Ross and screenwriter Norman Krasna (Hands Across the Table, Wife vs. Secretary, Fury, Mr. & Mrs. Smith) made a deal with RKO to release the film, and Krasna wrote a script that borrowed its department store setting from his story for Bachelor Mother (1939), which starred Ginger Rogers as the shopgirl.

(The deal would result in just one more picture – A Lady Takes a Chance (1943), with Arthur as a New Yorker who falls for a cowboy played by John Wayne while on a bus tour of the west. Arthur would leave Columbia and Hollywood for semi-retirement a year later.)

Writing about Arthur in Romantic Comedy in Hollywood from Lubitsch to Sturges, James Harvey calls her "the most original of all the screwball women – if only because she did away with so much of the equipment, the ingenuity and the subversion and the gags."

"Possibly the most distinctive thing about Arthur is that she's always so nice: that's the only word for it. And that quality is central in her as it could never be in the Colbert or the Rogers heroine. It's also helpless: she could never have played the opposite qualities, as Hepburn and Stanwyck and Lombard occasionally did. Arthur has this special talent for making ordinary niceness on the screen seem somehow remarkable – and interesting. And with her this plainness often has the same mysterious effect, even the same exotic force at times, as more conventional glamour."

When Mary tells Higgins that the shoe department employees are "one big happy family" there isn't a trace of sarcasm. If Lombard or Rogers had made the older man an object of pity in front of a roof full of people it might have seemed more than a little cruel, but Arthur's sincerity – that voice, with its husky catch as it ascends along with her emotional candour – makes it excusable and genuinely empathetic.

Merrick-as-Higgins is bound to be transformed by his subterfuge, but it isn't just Mary who leads him along. He develops affectionate feelings for Elizabeth (Spring Byington), another older employee, a gentle spinster who has been holding Hooper and his proposals at bay while wondering if she should, considering her age, settle for security instead of love.

Byington turns up indelibly in films like You Can't Take It With You, Heaven Can Wait, Roxie Hart, Presenting Lily Mars and I'll Be Seeing You, but she gets just a little bit more to do with Elizabeth here, enduring Merrick's occasional boorishness and coaxing out a solicitous, even courtly side of the man that was obviously never useful in a boardroom. And it's always refreshing to see a romance between late middle-aged people get equal airtime with the one between a film's young romantic leads.

The best scene in the film is a double date the two couples take to Coney Island, the poor man's Riviera. Director Sam Wood (A Night at the Opera, A Day at the Races, Goodbye, Mr. Chips, Kitty Foyle, Kings Row, Casanova Brown) and cameraman Harry Stradling (Suspicion, Easter Parade, A Streetcar Named Desire, A Face in the Crowd) make a lot of stylistically interesting choices in the picture, setting the camera low, using wide lenses, even setting up dramatically lit compositions that anticipate film noir by a few years.

They match a second unit establishing shot of the thronged beach at Coney with ones that put Arthur, Coburn, Cummings and Byington at the bottom of a stockade of legs, the sand covered in litter, the ocean nowhere to be seen. Marooned in a sea of humanity, Merrick is unable to impress his fellow employees when a wildly expensive bottle of wine he draws from his wine cellar turns out to be corked plonk that not even a soda mixer can salvage.

"Too bad we had to ruin a bottle of pop," Joe says as he pours it out into the sand.

After a barefoot hunt along the boardwalk to return his rented bathing suit, Merrick ends up in the local police station when he tries to exchange his expensive watch for change to call his chauffeur. He and Elizabeth later pretend to nap in the sand while Mary and Joe talk about their doubtful future together and the hopelessness of his fight to unionize the store. Merrick ends up in possession of Joe's list of employees who've signed on to the union, and Mary is desperate to get it back when she discovers a card identifying Higgins as an undercover private detective.

There's a slapstick sequence in the shoe department stockroom where she tries to summon the courage to knock him out with a hiking boot that leads to another one in the store manager's office, which ends with Mary taking over the public address system to rally the employees to walk out and begin a wildcat strike, with picket lines outside both Neely's and Merrick's mansion.

The film's labour politics are impossible to ignore, and it's not surprising that a picture made on the cusp between the Great Depression and the US entry into World War Two is pointedly sympathetic with Joe and Mary and their nascent union as it paints Merrick at the start of the picture and his chorus of executive lickspittles as callous (though comic) villains.

Joe might be a rabble rouser, but he's also a patriot, as underscored in the scene at the Coney Island police station, where he makes the sergeant walk back from his threats to arrest Higgins and Joe by quoting Lincoln, the Constitution and the Declaration if Independence.

Krasna would enlist in the army a year after making The Devil and Miss Jones, making films while stationed at Camp Roach, which allowed him to live in his Los Angeles home for much of his time in uniform. Frank Ross and Arthur divorced in 1949. Neither men were involved in the kinds of political activities that would get them called to testify in front of the Standing Committee of HUAC after the war.

But despite the coy note at the start of the film, the story was actually inspired by a real-life sit-down protest at several Woolworth's stores, and in an echo of current events, the picture was released while the Screen Writers Guild were negotiating their first union contracts with the studios.

Writing about the film on the Film School Rejects website, Emily Kubincanek notes:

"Arthur often played working girls similar to Miss Jones, but they never challenged the status quo as she does in this movie. During this time in Hollywood, a star's persona was their most important attribute and usually controlled every role they played. Audiences grew to expect Katharine Hepburn to play challenging, quick-witted women and Gary Cooper to be the quiet yet fearless hero. Arthur's persona invited audiences to side with her good nature, but in this movie, they were siding with a cause society deemed parasitic. Arthur's persona gave audiences comfort and therefore projected harmless energy onto a union leader."

In an article by Eileen Jones for the leftist online magazine Jacobin titled "Before They Ran the Reds out of the Studios", it's stated that the picture "exemplifies how pro-worker Hollywood was just on the eve of McCarthyism." (Let's be generous and ignore the fact that Joe McCarthy was a divorce lawyer in Wisconsin when The Devil and Miss Jones was released, and his name wouldn't assume its later infamy until over a decade afterwards.)

"Today," Jones writes, "it's easy to deride conservatives who say that Hollywood is run by 'cultural Marxists' looking to poison the youth. But there was a brief period when pro-worker films were the norm and hundreds of talented filmmakers tried to subtly (and sometimes not so subtly) turn mass culture red."

(As an aside, it's hard not to take note when Jacobins are evoked as a cultural rallying point. You want to be generous and allow that people might not realize just what Jacobin rule in France led to, but sometimes you just have to believe it when intentions are telegraphed so openly. In the current political climate, a reasonable response might suggest starting an online counterpart called Tailgunner. But as my friend Kathy Shaidle used to say, the last thing the world needs is another online political magazine.)

At the end, Merrick has to reveal his true identity to his new friends in front of his quartet of corporate yes-men, in a scene full of whiplash revelations and hysterical overreactions. The film tumbles from there abruptly to a happy but wholly improbable ending after a double wedding on a cruise ship bound for Hawaii.

The Devil and Miss Jones was not only a box office hit, but it netted Coburn and Krasna Oscar nominations. (Coburn was nominated three times, and would win for The More the Merrier.) Its title would, in time, be evoked by the 1973 porn film The Devil in Miss Jones, reviewed seriously by Roger Ebert and praised by William Friedkin when it was released at the height of '70s "porn chic", which became fodder for gags by Johnny Carson and Bob Hope. But the less said about that the better.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.