On June 13th, 1945, a month after the defeat of Nazi Germany, the New York Times published an article titled "Teen-Agers are an American Invention." With peace in sight, the generation that was too young to fight in the war was being defined by the newspaper of record as being "not ready for the serious matters of adulthood." Still, this newly-minted demographic (whose emergence had been nearly a century in the making) was being invited to express itself with its own culture – "and the leisure and the unprecedented affluence of teenagers predispose them to accept the invitation."

Birthdays – and today is mine – often put us in a nostalgic mood. I'd be lying to you, though, if I gave the impression that this is a recent indulgence. Truth is that I've been obsessed with nostalgia since I was a boy, though I've only recently been able to pinpoint precisely why. If I could offer up one artifact to illustrate the why and when, it would be a record album – a double LP set – that was handed down to me by my brother-in-law when I was around ten years old.

My older sister's husband was over fifteen years my senior, and the years when they lived in the basement apartment of my mother's house just after they were married were a big influence on me, for a host of reasons, prime among which was Lou's record collection. My brother-in-law had the kind of expensive stereo gear that most young men spent wages on back then, and an impressive record collection that he frequently culled, passing his discards on to me to play on my considerably lower-fi record player (itself a hand-me-down from my sister).

One of those discards was the soundtrack album for George Lucas' American Graffiti. The film had been a massive hit when it was released the previous year, so Lou and Mary didn't play it for very long, but I became obsessed with its soundtrack – forty-one "golden oldies" that had been on the radio (with one key exception) for the decade leading up to the late summer day in 1962 when Lucas' film is set.

The film begins with a burst of static, then the once-familiar sound of a roll along the dial of an AM radio before Bill Haley and the Comets' "Rock Around the Clock" blasts out of the soundtrack. Haley's hit single has become shorthand for '50s rock and roll, thanks largely to Lucas' film and being the theme for the first two seasons of Happy Days. This makes it easy to forget just how revolutionary it was when it came out in 1954 and took a year to become the first rock and roll single to hit the top of Billboard's pop charts.

One thing that you read over and over is how powerful it sounded to that first generation of listeners, especially when they heard it blaring from cinema speakers at the start of Blackboard Jungle, the 1955 juvenile delinquent drama that helped break it nationally. As Frank Zappa would recall: "It was the loudest rock sound kids had ever heard at the time. I remember being inspired with awe. In cruddy little teen-age rooms, across America, kids had been huddling around old radios and cheap record players listening to the 'dirty music' of their lifestyle... But in the theatre watching Blackboard Jungle, they couldn't tell you to turn it down."

The song's impact was thanks to Milt Gabler, the jazz aficionado and record shop owner-turned-record producer, who featured the gunshot-like snare hits of session drummer Billy Gussak high in the mix. Lucas and his sound designer Walter Murch obviously wanted audiences to experience some of the power Haley's song had on early fans, and it bursts from the screen, an amplified echo of Blackboard Jungle, while the credits roll over saturated shots of Mel's Drive-In – the car hop diner at the centre of the teen social circle of the film.

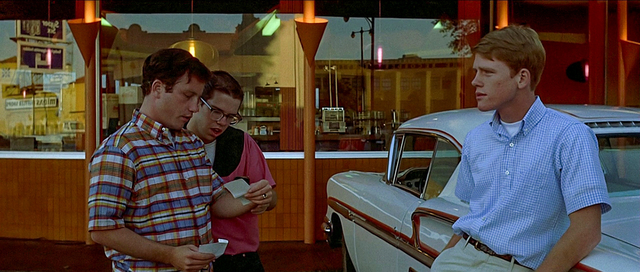

Curt (Richard Dreyfuss) and Steve (Ron Howard) are recent high school graduates, and this is their last night in their inland California hometown before heading east to college. Laurie (Cindy Williams) is Curt's sister and Steve's girlfriend and a high school senior. Terry "the Toad" (Charles Martin Smith) is their hapless, nerdy friend, apparently content to stay in town, and John Milner (Paul Le Mat) is an older buddy – the town's resident drag race champion, a greaser, car mechanic, and the coolest guy on the strip.

Lucas, who had been a gearhead when he was younger, gives everyone a car that fills out their identity. Milner drives what's probably the most classic hot rod of all time – a '32 Ford "deuce coupe" with a 283 Chevy small block engine, a '57 Chevy rear end and a four-speed transmission, painted in the hot yellow you'd see on Corvettes. Steve, class president and big man on campus, drives the sort of car affluent parents would buy their cherished son – a '58 Impala with a custom paint job, nosed and decked (emblems removed), and tuck and roll upholstery.

Curt, the intellectual of the group, signals his low-key rebellion with a Citroen 2CV – a pokey, tiny, old-fashioned foreign car that nobody would take cruising on the strip; he leaves it parked in a dark corner of Mel's parking lot for most of the film. His sister Laurie drives a '58 Edsel sedan – a family car, perhaps a hand-me-down. Terry the Toad drives a Vespa scooter; it's hard to imagine a vehicle that signals low status more, on this side of the Atlantic in any case.

In a 2010 essay, "Cars and Culture: The Cars of American Graffiti", in The American Poetry Review (of all places) Jack DeWitt writes that "it is the cars, stock or modified, that carry crucial messages about these different stories. One of the reasons that the movie is so convincing to car buffs is that Lucas and the co-producer Gary Kurtz did not pick particularly remarkable cars to embody teen culture. The cars of American Graffiti are representative cars rather than masterpieces – the sort of cars that you might have seen on an actual cruise night in 1962."

Curt is having misgivings about college and tells Steve that he's thinking of deferring his scholarship for a year and going to junior college. Steve, eager to leave, is conflicted about his relationship with Laurie, and proposes that they try an open relationship while he's away. He gives the keys and the custodianship of his Impala to Terry while he's away, opting to cruise the strip on his last night in Laurie's Edsel.

"He has been unhorsed and therefore unmanned," writes DeWitt.

Once the evening begins the group splits up and what follows is a picaresque story loosely centred on the town's main drag. Milner ends up with Carol (Mackenzie Philips), a bratty 12-year-old, riding shotgun with him while he half-heartedly dodges the challenge made by a cocky newcomer to the strip, Bob Falfa (Harrison Ford, in a '55 Chevy with a historically inappropriate 454 L-88 Corvette engine, built by hot rodder Richard Ruth for the 1971 film Two Lane Blacktop).

Curt bounces from backseat to backseat to sidewalk until he's shanghaied by The Pharaohs, a local gang led by Joe (Bo Hopkins), who decide to initiate him by pulling a dangerous prank on local cops manning a speed trap. Terry inexpertly cruises the strip in the Impala until he picks up Debbie (Candy Clark), a pretty and fast but not brilliant blonde. Steve and Laurie bicker, break up and make up over the course of the night, which climaxes at sunrise and a drag race between Milner and Falfa, with Laurie in the passenger seat of the Chevy.

George Lucas was encouraged to make American Graffiti by his friend Francis Ford Coppola, who challenged him to write something warmer and more human after the failure of his dystopic sci-fi debut feature THX 1138. (In context not much of a challenge; an industrial training film would have been warmer.)

Lucas based three of the film's characters on himself, at different times during his youth growing up in the Central Valley city of Modesto, California. Terry is his awkward, nerdy persona from his early high school years, while Curt is the more sophisticated young Lucas whose intellectual ambitions propelled him out of Modesto to film school. Milner is in the middle, and based on Lucas the gearhead who wanted to be a race car mechanic and driver, until a spectacular accident gave him second thoughts.

(I'd venture, though, that Le Mat's Milner looks more like a heroic projection of Lucas-as-greaser: the car he totaled while driving home from the library wasn't a deuce coupe or a Chevy gasser but an Autobianchi Bianchina, an Italian microcar based on the Fiat 500, with a tiny two-cylinder engine. Lucas souped it up and won races but it was still closer to Curt's 2CV than a kustom chop-top '51 Mercury like the one driven by Hopkins.)

Lucas had problems writing a story for Steve and Laurie, however, and turned to two friends – Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck, a married couple who were able to write dialogue that helps Lucas' film rise above the standard of the average coming-of-age film. Williams said that she didn't want to play Laurie but the much more free-spirited Debbie, even though Laurie's story paralleled her own high school relationship. You can't blame her – Steve and Laurie embody the top percentile of average American youth in nearly every way, but their characters might still be the key to how American Graffiti drew an audience that far exceeded both the genre and the filmmakers' expectations.

The production was troubled. Lucas had problems pitching his story, and a commitment by United Artists fell through before it was taken up by Universal. Filming, once it finally began, was supposed to take place in San Rafael, in Marin County, but after a disastrous first night's shoot, the city pulled the plug on their location permit and Lucas and Kurtz had to hurriedly negotiate a new deal in Petaluma, just to the north in Sonoma County.

Still imagining himself as a radical independent filmmaker, Lucas started shooting with two cameramen but no cinematographer; after complaints about the lack of light in a movie shot almost entirely at night, he had to beg his friend Haskell Wexler, to sign on as "visual consultant" for the picture. Wexler – very much in demand as a commercial cinematographer after making Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, In the Heat of the Night and The Thomas Crown Affair – spent six weeks flying from Los Angeles to Petaluma every night to work on Lucas' film, flying back in the morning.

Lucas decided not to film in his hometown, Modesto, because much of its downtown strip had been demolished and rebuilt in the decade since he'd cruised there. There had been a lot of changes between 1962 and 1972, and part of Lucas' motivation for the film was to recapture the look and sound of cruising and the California car culture of his youth, which had transformed or disappeared – like downtown Modesto – in that tumultuous decade.

(Mel's Drive-In stood in for Burge's, a car hop diner at one end of Modesto's cruising strip that closed in 1967. The Mel's in the film was located on South Van Ness in San Francisco, and was reopened just for filming, then demolished by the time the film was released.)

In his book Teenage: The Creation of Youth Culture, Jon Savage writes that "by the early 1940s, American adolescents had succeeded in creating a world quite distinct from both adults and children." Teenage car culture could be found almost anywhere, but it's no coincidence that it thrived most of all in California, where the sun shines every day (and there's no snow or road salt to eat away at body panels or frames) and the money was in the entertainment business and the defense industry.

"The American future," Savage wrote, "would be ordered around pleasure and acquisition: the harnessing of mass production to disposable leisure items like magazines, cosmetics, and clothes as well as military hardware."

A lot had happened in American youth culture since its birth at the end of World War Two, but a glimpse at photos of crowds of kids in record shops or at a Sinatra concert in 1944 is remarkably similar to teenagers nearly two decades later, right down to the dungarees, plaid shirts, Brylcreemed hair and bobby socks. American Graffiti was one of the first films to understand that even the recent past looked very different from the present day, and despite a few lapses in hair styles, dance steps and car modifications that only an eagle eye will pick out, Lucas and his production crew did a remarkable job recreating a teenage summer night on the cusp of some very big changes.

Everyone seems to understand this, especially Le Mat's Milner. He complains early on that the strip is shrinking, and the pickings are getting thinner. Steve chews out Curt when he says that he's thinking of staying by warning that he'll "end up like John...seventeen forever." But Milner is painfully aware that time is passing him by, and that he won't last forever as the big dog on the strip.

He even feels out of step with the music on the radio; when Carol turns up the Beach Boys on the car radio, Milner turns it off angrily, saying that he hates surf music. "Rock and roll's been going downhill since Buddy Holly died," he tells her, which suggests that John might have had a career as a rock critic in his future.

That music turned out to be crucial – to both Lucas' vision for the picture and its success. He wrote the first drafts of the screenplay with music in mind, scoring scenes to 45s from his own teenage collection, and by the time the producers negotiated the rights to use all the original songs he needed (after first suggesting that they hire an orchestra to record soundalikes) there was no money left for an orchestral musical score, so scenes that happen away from a radio play out with just dialogue and the sound effects created by Walter Murch.

The soundtrack album, with its bright gatefold cover featuring a centerfold-style airbrush drawing of an idealized car hop waitress, is full of interesting choices. It reveals that the teenage Lucas had a big thing for doo-wop ballads ("A Thousand Miles Away", "Only You (And You Alone", "I Only Have Eyes For You", "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes"). It also underscores how pop music since the emergence of the teenage market had responded with songs about teenagers ("Teen Angel," "Sixteen Candles, "You're Sixteen", "Almost Grown") that would have been unimaginable even in the latter years of the swing era when the teenager emerged.

Conspicuous by his absence is anything by Elvis Presley. This might have been a licensing issue – one imagines that Colonel Tom would have made anyone pay a premium for his songs. But there's no Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash or Jerry Lee Lewis; rockabilly and Southern white music clearly played little to no part in Lucas' memories of his Californian youth.

A few songs point to the future, which everyone watching the film was going to be transformative. I had heard Booker T and the MGs "Green Onions" on AM radio oldies playlists, but having the song on the soundtrack album (it plays during the lead-up to the climactic drag race) gave me a chance to obsess over this striking, angular, groove-heavy instrumental that fed into a growing obsession with R&B and soul music.

And there's "Surfin' Safari" by the Beach Boys – that flashpoint of friction between Milner and Carol – though it's not the only Brian Wilson song on the album.

While Steve, Laurie, Terry, Debbie, Carol and John go about their very mundane challenges, Curt's journey through the night takes on a mythic tone. First there's the Woman in the T-Bird – a gorgeous blonde (Susanne Somers) in a white '56 Thunderbird who beckons to Curt, siren-like, giving him a purpose during what started as an aimless night.

And there's Wolfman Jack, playing himself as he hosts the graveyard shift on the big AM station that blankets the valley with a powerful signal rumoured to come from Mexico. Lucas had listened to Wolfman Jack when he was a teenager, and thanks to Coppola they were able to get him for the film, playing what at first seems like a lonely radio engineer in the control room of a radio station just outside town, cueing up 45s and prerecorded tape "carts" with the Wolfman's on-air spiels.

Both the blonde and the Wolfman point Curt to the decision he needs to make about his future – one dismal potential scenario glimpsed in a scene where he meets up with Mr. Wolfe (Terence McGovern), a favorite teacher and mentor of sorts, who also tried and failed to escape to college out east, and seems about to be trapped by the consequences of an affair with one of his students.

When the night finally ends it's Steve who decides to stay while Curt heads east to college; a white T-bird follows the plane along a country road as Curt turns on his transistor radio, and as "All Summer Long" by the Beach Boys plays on the soundtrack we learn that neither John nor Terry survived the '60s, the former dying in a car crash just over two years later, the latter a year after that in Vietnam. Steve is an insurance salesman, presumably married to Laurie. Curt is "a writer living in Canada."

Even when I finally saw American Graffiti for the first time – actually years after I got the soundtrack album – I felt sorrier for Curt than any of his friends.

"All Summer Long" was released in 1964, two years after the night in the film; after JFK's assassination and the start of the British Invasion. It's part of Brian Wilson's ramp-up to the stunning musical sophistication of Pet Sounds, a deceptively jaunty number featuring fife and marimba that lyrically moves between a catalogue of the kinds of fun things it seemed only kids in California did (horseback riding, "Hondas in the hills") and the sharp ache of knowing that September won't just send everyone back to school, but nudge the singer and the girl he's singing to closer to less carefree adult lives.

Wilson's strange genius captured the essence of nostalgia – a longing not just for a time long in the past, perhaps before our own memories begin, but for moments just passing, and the sense of loss, longing and regret that grows heavier as we get older.

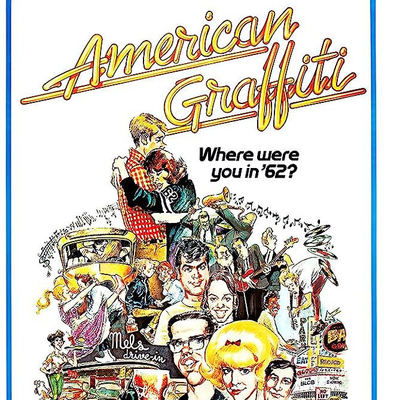

It's key to why American Graffiti was such a massive, unprecedented hit – earning $140 million at the box office on a budget of just over $750,000, a return on investment that has apparently never been duplicated by any other movie. "Where were you in '62?" read the tagline on the poster designed by Mad magazine artist Mort Drucker, and there were obviously a lot of people (like, presumably, my brother-in-law) who were asking themselves that question in 1973. And being members of the Baby Boom generation, there were a lot of them.

The soundtrack album was also a hit, going triple platinum in the US and leading to not one but two subsequent double-album collections of oldies, only two of which were songs left off the original soundtrack album. And then there was Happy Days, the Garry Marshall-produced ABC sitcom that was so clearly meant to exploit the success of Lucas' movie, with a starring role for Ron Howard and, eventually, one for Cindy Williams in a spin-off, Laverne & Shirley.

There would be a sequel, More American Graffiti, released in 1979, produced by Lucasfilm and written and directed by Bill L. Norton, though apparently with considerable input (some would say interference) by Lucas. It followed up on the fates of the characters in that final card before the credits (though not Curt; Dreyfuss' asking price was too high) over a sprawling, complex storyline set during four separate days as the '60s start looking more like The Sixties.

I have never seen it. It was a flop when it was released, and critically savaged, though it has developed apologists and a tentative following in recent years. I may give it a shot one day; enough time has passed that I can forgive – or forget – an ill-conceived sequel which does not, after all, diminish the importance of, or my fondness for, the original.

My generation would eventually get its own American Graffiti – Richard Linklater's Dazed and Confused (1993), set at the start of summer in 1976, just a year before I began high school. It was another coming-of-age story with an evocative soundtrack album (with its own sequel) full of radio hits (a trend that Lucas' film effectively started), and even had its own Milner character – Matthew McConaughey's Wooderson.

But I never responded to Linklater's film the way I did with American Graffiti, perhaps because my memories of the '70s – actual and lived – are both vivid and unpleasant, perhaps because the soundtrack was so much more familiar, and entirely lacking any sense of discovery. And I'm one of those people who will insist that American Graffiti was, and remains, the best thing George Lucas ever did – a melancholic underdog of a film that showed us how time passing can actually make a sound.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.