There is an overwhelming consensus that humanity is returning to a preference for absorbing information through pictures and video rather than text, and that the millennia and a half where the written word reigned is ending. This might sound apocalyptic to some minority of us, but it's hard to deny, and in any case it didn't become apparent with the rise of YouTube and TikTok influencers but decades ago, when a rumpled Englishman who looked like he emerged from the wood paneling of a university library told the story of western civilization with a TV series.

I feel like one of those people dismayed at the decline of text, but if I'm honest I'm like most of us and have always learned more, and faster, from the visual image – moving or still. I can name a half dozen TV documentary series that did more to form my worldview than almost any book I've read, back to the torpor of my TV junkie childhood. I want to use up a few dozen of what we once quaintly called "column inches" here talking about those shows, starting with the one that did more to make all the information I was getting from school, books, movies and pop culture cohere into a powerful narrative.

Civilisation – its official title, though it's always referred to as Kenneth Clark's Civilisation – debuted on February 23rd, 1969 on BBC2. It was not the first ambitious, comprehensive documentary series made by the BBC, but it was the first one broadcast in colour, which may account for its popularity and longevity. It cost £500,000 to produce and attracted unexpected numbers of viewers – 2.5 million in the UK, and 5 million in the US when it was aired on PBS a year later. The book Clark wrote as a companion has never been out of print, and its success paved the way for countless subsequent documentary series, from Alistair Cooke's America (1972) to Jacob Bronowski's The Ascent of Man (1973) to Carl Sagan's Cosmos (1980).

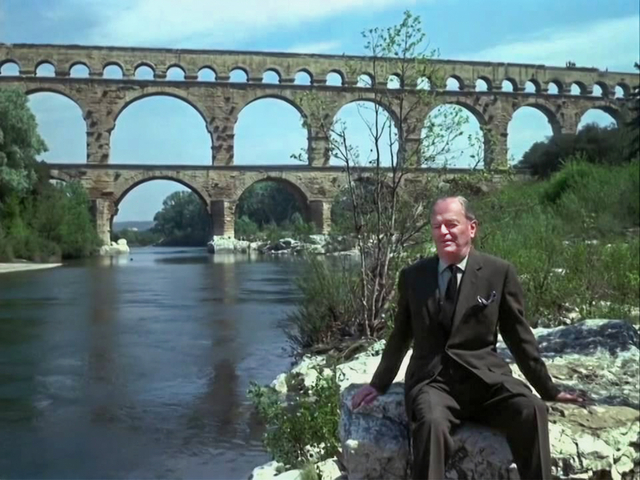

The full title of the series was Civilisation: A Personal View by Kenneth Clark; this makes explicit the subjective nature of what we're about to see and hear, and it begins – after a preview montage set to organ music by Cesar Franck – with Clark standing by the Pont de l'Archevêché on the south bank of the Seine across from Notre Dame.

He tells us that civilisation as we know it might seem robust, but that at some point in history it had virtually disappeared, and that we only recovered it by "the skin of our teeth" – not coincidentally the title of the first of Civilisation's thirteen episodes. We will, for the purposes of this series, begin at that point, just after the fall of the western Roman Empire, at the start of what's called (not quite accurately) the Dark Ages, and try to understand what we mean by civilisation by examining what we see along the way.

"What is civilisation?" Clark asks. "I don't know. I can't define it in abstract terms – yet. But I think I can recognise it when I see it; and I am looking at it now." (I can't help but wonder what Clark – who died in 1983 – might have said about Notre Dame nearly burning to the ground just over four years ago. It occurs to me that the skin of our teeth offer barely any protection at all.)

He goes on to tell us that "writers and politicians may come out with all sorts of edifying sentiments, but they are what is known as declarations of intent. If I had to say which was telling the truth about society, a speech by a Minister of Housing or the actual buildings put up in in his name, I should believe in the buildings."

Kenneth Mackenzie Clark, later Sir Clark, later Baron Clark, was born into unmistakable privilege, and came to his fascination for art with the writings of John Ruskin and by working for influential collector and scholar Bernard Berenson, helping him revise a book about Florentine painters. He became the director of the National Gallery at just 30, and Surveyor of Pictures to Kings George V and George VI. (His successor in the latter post would be Sir Anthony Blunt, Soviet spy and member of the Cambridge Five.)

As a cultural bureaucrat Clark had a reputation as a populist and would open the National Gallery early on days when the FA Cup finals were being played, hoping that football fans would find their way inside. With the artworks evacuated and in storage during the war, he volunteered for national service and ended up in charge of the film division of the Ministry of Information, which led in a roundabout way in the '50s to Clark becoming chairman of ITV, Britain's first independent television broadcaster, despite not owning a television set.

He began making documentaries, starting with Is Art Necessary? in 1958, followed by Five Revolutionary Painters, The Royal Palaces of Britain and Three Faces of France. They gave him a reputation for being authoritative but not excessively snobby, and when David Attenborough became controller of the new BBC2 channel, he approached Clark to present a series on great paintings, which expanded as he developed it to encompass the whole topic of civilisation.

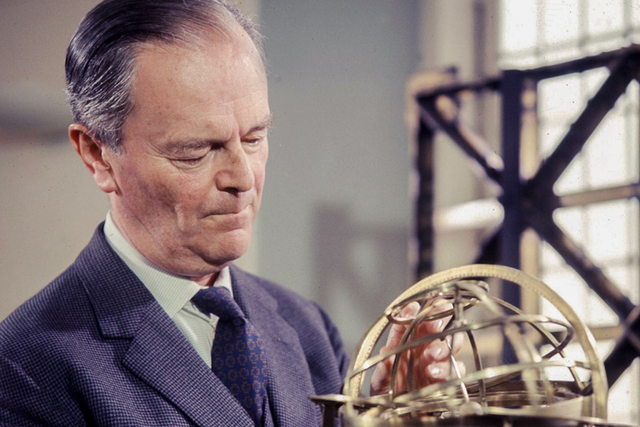

I can't imagine how someone like Kenneth Clark would be allowed to present a series like this today, on any BBC channel or equivalent broadcaster or streamer, anywhere in the English-speaking world. He proudly calls himself a Scotsman, but there's no trace of regional accent in his voice, which clips its vowels exactly as you'd expect from someone of his background (Wixenford, Winchester, Trinity College Oxford).

But he doesn't seem off-puttingly posh; Clark embodies the low key, slightly shabby style of the untitled rich, and his onscreen attire tends to shapeless and functional – what Michael Collins writing for The Critic last year described as "soil-coloured ties and slurry-coloured suits," and "a mouth filled with teeth that were so bad you'd struggle to find similar on the poorest of the English working class."

(Abysmal dentistry was one of the leveling factors for several generations of Britons across the classes. A high school friend born in a milieu adjacent to the one that produced Clark once told me that his decent mouthful of teeth had to do with his family living abroad, and a period in a Swiss boarding school at a crucial age.)

Early episodes of Civilisation have Clark work to describe the difference between culture and civilisation. He admires the brutal vigour and craftsmanship of barbarians like the Vikings who pillaged, burned and raped their way through the villages and monasteries of the English and Irish coasts, but says (I'm quoting from his book more than the series' script) that "civilisation means something more than energy and will and creative power: something the early Norsemen didn't have, but which, even in their time, was beginning to appear in Western Europe."

"How can I define it? Well, very shortly, a sense of permanence. The wanderers and invaders were in a continual state of flux. They didn't feel the need to look forward beyond the next March or the next voyage or the next battle. And for that reason it didn't occur to them to build stone houses, or to write books...Civilised man, or so it seems to me, must feel that he belongs somewhere in space and time; that he consciously looks forward and looks back. And for this purpose it is a great convenience to be able to read and write."

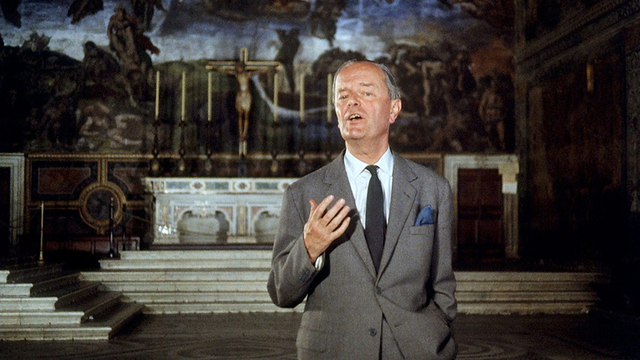

Probably the most unfashionable thing Clark has to say about civilisation as it developed in Western Europe is that it would not have cohered or thrived or evolved without the church – and more specifically the Catholic Church, which had the sort of universal power and influence that transcended empires or kingdoms or duchies or city states in a feudal world for nearly a thousand years before the schisms of the Reformation.

Clark's voice and narration betrays growing enthusiasm when he takes us on a tour of ecclesiastical Europe as it evolves from Romanesque to Gothic. He talks about the crucial importance of the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny but can't show it to us as, alas, it did not survive the French Revolution. So he takes us to Moissac and Vézelay and St. Denis and Chartres, where the camera lingers on the line of sculptures of royals.

"Do not the kings and queens of Chartres show a new stage in the ascent of western man?" he asks. "Indeed I believe that the refinement, the look of selfless detachment and the spirituality of these heads is something entirely new in art. Beside them the gods and heroes of ancient Greece look arrogant, soulless and even slightly brutal. I fancy that the faces which look out at us from the past are the surest indication that we have the meaning of an epoch."

Clark is openly and unapologetically in awe of genius, and he searches for authorship in the murals and sculptures and architecture of the churches and abbeys we visit. Not surprising that he becomes more effusive when we finally reach the Renaissance, when work is signed and artistic reputations become celebrated and sought out by merchant princes and the emerging middle class.

An audience today might find Civilisation too leisurely in pacing; long stretches go by where the camera surveys some courtyard or mural or landscape while period music plays in the background. Clark remains silent, waiting until he thinks we've absorbed the beauty and significance of what we're seeing before he returns with some explanation or to make a point, but his tone is never condescending and we never feel like we're being lectured. He's like an excellent tour guide – enthusiastic but not pedantic, superb company, never overbearing, and willing to concede that we can discern what he sees without excessive prompting.

(By contrast most BBC presenters today come off like associate lecturers in love with the sound of passages drawn from their latest book. PBS hosts have the demeanor of teachers at a decent high school surveying bored faces looking for a glimmer of interest. Worst of all is Canada's public broadcaster, the CBC, which favours a default tone best described as an overenthusiastic primary school teacher nearer their degree than retirement – you always feel like they're about to pull out a pitch pipe and lead the class in a song.)

Alongside the obvious genius of Michelangelo, Botticelli, Raphael and da Vinci, Clark takes time to note how the Catholic Church rallied against the assault of the Protestant Reformation with "a period of sanctity...almost equal to the twelfth (century). St. John of the Cross, the great poet of mysticism; St. Ignatius Loyola, the visionary soldier turned psychologist; St. Theresa of Avila, the great headmistress, with her irresistible combination of mystical experience and common sense; and St. Carlo Borromeo, the austere administrator – one does not need to be a practising Catholic to feel respect for a half-century that could produce these great spirits. Ignatius, Terese, Filipo Neri and Francis Xavier were all canonised on the same day, 22 May 1622. It was like the baptism of a regenerated Rome."

(It might come as no surprise to learn that Clark, born into the Church of England, converted to Roman Catholicism before he died. You imagine that he took the iconoclasm of Protestant zealotry and all those vandalized, gutted and whitewashed churches as a personal affront. He knew what afflicted the Anglican Church decades ago; you wonder what he might see troubling Rome today.)

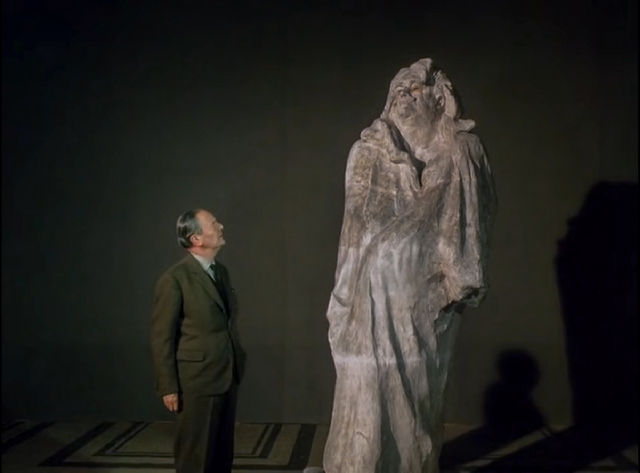

There's a shot that recurs over and over in Civilisation, where the camera rests on some massive sculpture in the centre of a shot, while Clark – dwarfed in its shadow – walks into the frame to look up at the looming presence of Michelangelo's David, or the statue of Thomas Jefferson in his monument in Washington, DC, or Rodin's sculpture of Balzac. He can't hide his humility in the presence of genius; Clark is an unashamed supplicant, content to explain and celebrate the world-changing importance of an artist or thinker without imagining himself as their equal.

There's another shift in tone when the series arrives at the 18th century, the Enlightenment and the unrest and horror unleashed in the battles between reason and romanticism – the era that birthed the modern world, and all the issues that trouble us today. It came about – coincidentally or not – with the sudden disappearance of Christianity as "the chief creative force in western civilisation."

This led to the worship of nature, a word and an idea so vast and vague that it could – and did – mean anything to anyone who sought to use it as a guiding principle for their ideology. There was a time when nobody painted or wrote about mountains except as a setting or a background, but then came Thomas Gray and, especially Jacques Rousseau, who rebelled against Descartes and expressed the wholly reactionary concept that, as Clark puts it, "I feel therefore I am."

"It was an intellectual time bomb," Clark writes, "which after sizzling away for almost two hundred years has only just gone off, whether to the advantage of civilisation seems rather doubtful."

The "discovery" of nature led inevitably to the Romantic movement, which Clark judges as having its political expression in revolutions – first in American and then, most of all, in France. There the revolutionaries were in a battle against corruption and an unjust, unreformable system but Clark reminds us that "her leaders suffered from the most terrible of all delusions. They believed themselves to be virtuous. Robespierre's friend St Just said: 'In a republic which can only be based on virtue, any pity shown towards crime is a flagrant proof of treason.'"

And so the September Massacres and the Great Terror and the reprisals and finally Napoleon Bonaparte, arriving just in time to preside over the inevitable pendulum swinging back, to lead a nation on the brink of collapse just a few years earlier on to a campaign of conquest across Europe – and to set up the first modern secret police. To represent it onscreen Clark takes us to the Castle at Vincennes and its dungeons, where political prisoners were held and executed from before the Revolution to as recently as the end of World War Two.

This is followed by a montage of revolutions, set to the prisoner's chorus in Beethoven's Fidelio: France in 1830; Spain, France, Hungary and Germany in 1848; Italy in 1861; France in 1871; Russia in 1917; Spain in 1936; Hungary in 1956; France and Czechoslovakia in 1968.

"As far as freedom is concerned, I'm afraid recent revolutionary movements haven't got as far forward," Clark sighs as it ends. (The inclusion of the then-recent riots in France feels modish, especially now, with the generation of soixant-huitards so far in the rear-view mirror.) In the book he's less reductive: "Always the same pattern: the same idealists, the same professional agitators, the same barricades, the same soldiers with drawn swords, the same terrified civilians, the same savage reprisals. In the end one can't say that we are much further forward."

For the series' final chapter, Heroic Materialism, Clark grimly tells the story of how humanitarianism arose as a reaction to the brutal economics and demography of the Industrial Revolution as it played out all over Europe and parts of America but especially in England, which saw the spread of vast urban slums unimaginable a century earlier, and poverty that both citizens and government struggled to comprehend, never mind remedy.

Here more than anywhere there arose a passion for technology and progress, its hero the engineer, his heroic creation the railways that spanned the country. "In sixteenth-century Florence Vasari wrote the Lives of the Painters," Clark tells us. "In nineteenth-century England Samuel Smiles, that reliable barometer of his time, wrote the Lives of the Engineers." But Smiles, a conventional man who kept his eyes lowered to the horizon, almost completely ignored the most heroic man in England's engineering pantheon: Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

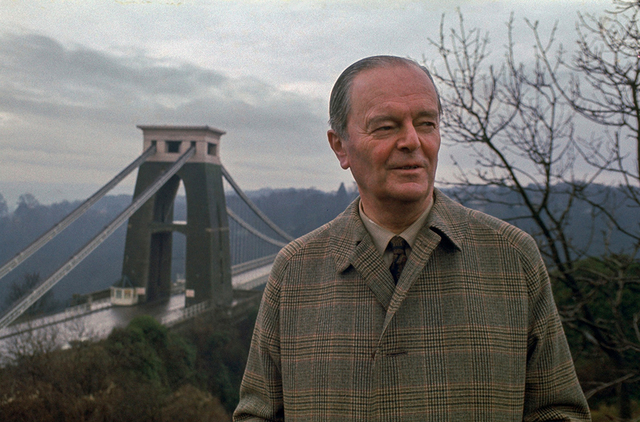

Brunel had the kind of life Clark obviously relishes re-telling – a series of disasters, victories, then disasters, each greater than the last, changing the landscape of England utterly until it culminates in a suitably heroic ending: "Brunel's last work was the bridge over the Tamar at Saltash; it was completed just in time for him to cross it on the first train, lying on his death-bed."

Clark begins the series talking about churches and cathedrals, before showing us painting and sculpture and extolling the artists who affected their era as much as it influenced them. By the end he's talking about bridges and skyscrapers and science; creativity had migrated again, to yet another profession more in tune with the times. "When scientists could use a mathematical idea to transform matter they had achieved the same quasi-magical relationship with the material world as artists. When I look at Karsh's photograph of Einstein I ask myself, Where have I seen that face before? The aged Rembrandt."

(While I appreciate Clark's point, as a photographer I have to note that the Rembrandt was a self-portrait, while Einstein's portrait has an author – the photographer Karsh, who certainly knew Rembrandt and whose authorship would involve a decision to portray the scientist as Rembrandt's echo. As much as I admire Clark, I suspect he didn't consider photography the equal of painting or sculpture, or imagine that Karsh could have as much creative agency as Gericault or van Eyck.)

No surprise that a man like Clark, whose family made its fortune in textiles, should have a guilty conscience about the Industrial Revolution. But I feel obliged to note that the ongoing progress of that revolution would move my family from agrarian labour in Ireland and Scotland and industrial tenements in Merseyside and the Northwest to the comforts of lower middle-class life in Canada at around the time Civilisation aired.

It was here that I could watch Clark's program – certainly not when it first aired but by some point in the early '80s – and respond to it with wonder. Finally someone provided a narrative to understand all those centuries of culture and creativity in context, extricate it from its indifferent presentation in the classroom and give me a point from which I could begin to really learn as much as I could.

"I should doubt if so many people have ever been as well-fed, as well-read, as bright-minded, as curious and critical as the young are today," Clark says, while the camera surveys the students at the University of East Anglia, one of the new provincial "red brick universities," in their miniskirts and sideburns. He warns us not to "overrate the culture of what used to be called 'top people' before the wars":

"They had charming manners, but they were as ignorant as swans. They did know something about literature, and a few had been to the opera. But they knew nothing about painting and less than nothing about philosophy...The members of a music group or an art group at a provincial university would be five times better informed and more alert."

Clark's optimism is endearing, but I look at those students and see the professors and lecturers I remember from university just over a decade later, themselves busy training the future lecturers and professors who would make the modern university such a laughingstock, and so very nearly the greatest enemy of inquiry and debate.

The sorts of places that seek to bury Clark's Civilisation as a relic, though Clark could already feel the winds moving against him. "I know next to nothing about science," he says, "but I've spent my life in trying to learn about art, and I am completely baffled by what is taking place today. I sometimes like what I see, but when I read modern critics I realise that my preferences are merely accidental."

Clark's program was criticized at the time for its focus on Western Europe, and for subscribing to the "great men" view of history. In the foreword to his book, he drily wrote that he "didn't suppose that anyone would be so obtuse as to think that I had forgotten about the great civilisations of the pre-Christian era and the East. However, I confess that the title has worried me. It would have been easy in the nineteenth century: Speculations on the Nature of Civilisation as illustrated by the Changing Phases of Civilised Life in Western Europe from the Dark Ages to the Present Day. Unfortunately, this is no longer practicable."

In any case the BBC felt moved in 2018 to produce Civilisations, a corrective to Clark, with episodes presented by Mary Beard, David Olusoga and Simon Schama. Reviewing it, the Washington Post's art critic compared it to Clark's original and said that "neither Lord Clark's benign pomposity nor his open disdain for contemporary culture would fly. His focus, too, on the West seems perverse in our globalized era, when we all have become more conscious of the complexity of interactions between cultures throughout history." But the BBC's own arts editor called Civilisations a "patchwork...with rambling narratives that promise much but deliver little in way of fresh insight or surprising connections."

Before the end of the last episode, Clark turns to the camera and professes to being "a stick in the mud."

"I hold a number of beliefs that have been repudiated by the liveliest intellects of our time. I believe that order is better than chaos, creation better than destruction. I prefer gentleness to violence, forgiveness to vendetta. On the whole I think that knowledge is preferable to ignorance, and I am sure that human sympathy is more valuable than ideology..."

It's a moment I would call heroic, perhaps more now than then. And he ends the series with a warning: "I said at the beginning that it is a lack of confidence, more than anything else, that kills a civilisation. We can destroy ourselves by cynicism and disillusion, just as effectively as by bombs. Fifty years ago W.B. Yeats, who was more like a man of genius than anyone I have ever known, wrote a famous prophetic poem:"

"Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon this world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.