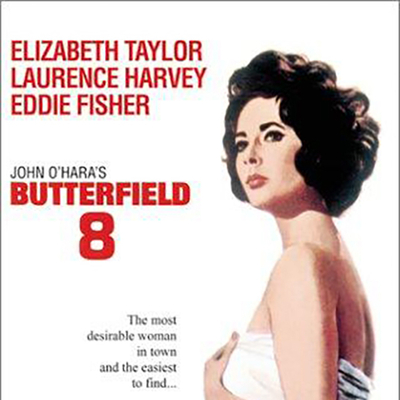

The old Production Code was walking dead by the end of the '50s, staggering to the grave with mortal wounds inflicted on it by films as varied as The Moon is Blue (1953), On the Waterfront (1954), The French Line (1954), The Man with the Golden Arm (1955), Baby Doll (1956) and the word "panties" in Anatomy of a Murder (1959). Whether it was audiences or studios or creative filmmakers like Elia Kazan who wanted it dead the most is a matter for debate. What we do know is that celebrity and scandal would join forces with art and the box office, and that by the turn of the '60s the Code would be assaulted by no less than Elizabeth Taylor in her figure-hugging slip, and that the Code would lose once again.

Taylor began the decade playing ingenues in films like Father of the Bride and The Big Hangover and taking her first walk down the aisle at nineteen with hotel heir Conrad Hilton Jr. She would end it a widow, married to her fourth husband, Eddie Fisher, the best friend of her late, third husband Mike Todd – an infamous episode that saw her painted as a homewrecker in the press for tempting Fisher away from Debbie Reynolds while still in her widow's weeds.

All this would have been a catastrophe for her studio, MGM, back when it was run by Louis B. Mayer, but Mayer was ousted by 1951 and dead by 1957 and the studios were running on permanent crisis mode by the end of the decade. Instead of trying to bury scandals, they saw opportunity in them – and that meant casting Taylor (and Fisher) in an adaptation of John O'Hara's 1935 novel BUtterfield 8, in a role that conspicuously echoed the current infamy of her public image.

The first scene of the film is fascinating, mostly because it's nearly dialogue free – a reprieve one will appreciate, trust me. Gloria Wandrous (Taylor) wakes up in a bed not her own from an apparently restless sleep, her unease and discomfort highlighted by Bronislau Kaper's hyperventilating score, which marries dissonant Avant Garde tone clusters with Rachmaninoff-like runs up and down the piano. The phone on the bedside table is off the hook, and we hear a door close in the background while she's still struggling to emerge from sleep.

She hunts for a cigarette, throwing empty crumpled packs over her shoulder as she does; a puff on a small cigar she takes from the nightstand triggers a coughing fit, which prompts her to pour a tall drink of whiskey from a decanter. (There are decanters full of spirits all over this well-decorated apartment, and we're not supposed to consider this noteworthy.) Gloria finds her dress on the floor, torn open down the front; she balls it up grimly and, while the camera pans down to the carpet, struggles into a slip and a pair of heels.

In the bathroom she dips a toothbrush into her glass and brushes her teeth, gargling with the whiskey. Exploring the apartment she discovers a woman's dressing room; after sampling the perfumes on the dressing table she opens a closet and discovers a mink coat, which she tries on briefly before opting for a less ostentatious cloth coat with a wide fur collar. Moving on to the living room she finds her purse with an envelope containing $250 and a written apology for ruining her dress.

Enraged, Gloria writes "No Sale" in lipstick on a mirror, stuffing the bills into the gilt ornament on the top of a table clock, then heads back to the dressing room to exchange her coat for the mink. She surveys the room with defiance, then picks up the phone and calls "Butterfield 8" – apparently her answering service – and instructs them that she will only take calls from a "Mr. Liggett" that day. Before leaving she takes a full crystal decanter from a sideboard and pulls a bill from her clutch, leaving it in its place.

The scene is a prelude to what my generation would call the "walk of shame," and it paints a vivid picture of the morning after the night before that makes you feel the sore, nicotine-scarred throat and sour mouth even without Kaper's portentous score. We know a lot about Gloria before she hails a cab and gives the driver a Greenwich Village address. It's Sunday morning.

John O'Hara is one of dozens, perhaps hundreds, of once-famous literary celebrities who almost no one reads or talks about anymore. BUtterfield 8 (the title referred to the then-new telephone exchange for New York's Upper East Side) was one of his acclaimed early novels, set in the early years of the Great Depression, when the worst damage from the market crash hadn't revealed itself.

O'Hara – who sounds like a difficult man to like, especially when he was drinking, which he did for the bulk of his most productive years – was famous for remarkably frank, even scurrilous stories, focused largely on class, sex, status and booze, in varying order. A resentful man, quick to sense a social snub, he made his reputation with his short stories (most of them published in the New Yorker) but his novels have an intensity that comes from the author's relentlessness – always drilling down on the dismal backstories and bad decisions his characters might have made before we encounter them on their way to making more:

"It was a good job of tearing he had done and he was embarrassed about that. From the way she had behaved when once he got her into bed there was no reason to suspect her of being a teaser, but why had she been so teaser-like when he brought her home? They were both drunk, and he had to admit that she was a little less drunk than he, could drink more was what he was trying not to admit. She had come home with a man she had met only that night, come to his apartment after necking with him in a taxi and allowing him to feel her breasts. She had gone to his bathroom and when she came out saw him standing there waiting for her with a drink in his hand she accepted the drink but was all for going back to the livingroom. 'No, it's much more comfortable here,' he remembered saying, and remembering thinking that if he hadn't said anything it would have been better, for as soon as he spoke she said she thought it was more comfortable in the livingroom, and he said all right, it was more comfortable in the livingroom but they were going to stay here."

Most of all O'Hara was famous for his dialogue, which did a lot to delineate his characters and, nearly a century later, still feels remarkably contemporary; along with all the frank talk of sex and social status he fills his stories with people who don't seem at all like nearly century-old relics that the mind's eye imagines in shaky black and white, in high-collared shirts and low-waisted dresses.

Which was a shame considering the script that Charles Schnee and John Michael Hayes delivered to producer Pandro S. Berman and director Daniel Mann. Both writers had impressive resumes (Red River, The Furies, The Bad and the Beautiful, Rear Window, The Trouble with Harry, The Man Who Knew Too Much) but their adaptation of O'Hara's novel – a very loose one, even accounting for updating it to a contemporary setting – was dreadful, and both Elizabeth Taylor and Eddie Fisher knew it.

In his 1999 autobiography Been There, Done That, Fisher says that Taylor didn't want to take the part of Gloria. "MGM warned her that if she refused to do the picture they would suspend her and she would not be able to work for two years. She was outraged. Livid. She hated them for making her play this particular part... Finally she told the producer, Pandro Berman, that she hated the script, that she would be as uncooperative as possible and that the studio would regret forcing her to do it. But she would to it, she said, if they replaced David Jansen, who was cast to play her best friend, with me. The character I was supposed to play was named Eddie, but because I was playing the role they changed his name to Steve. That was about the extent of their creativity."

Taylor and Fisher referred to the film in private as Butterball 4, and it really is the sort of overcooked melodrama that gives Hollywood films from the '50s a bad name. Take, for instance, this dialogue between Gloria and Liggett (Laurence Harvey) after the two of them have begun falling in love, and Liggett takes her to visit his prized possession, a sailing yacht that's seen better days:

Liggett

Come aboard and sign on. But I warn you, the crew hasn't touched land or seen a woman in three months.

Gloria

Crazy. Where are you bound for, captain?

Liggett

Out of frustration. Bound for ecstasy.

Gloria

I've heard a lot about ecstasy.

Liggett

It's everything they say. And more.

Gloria

If you'd kindly show me to my quarters, captain, you can lift anchor any time.

You'll have to trust me that you'd never find dialogue this arch or stilted in an O'Hara novel. (There are people out there who can't see the difference between this sort of thing and a Douglas Sirk picture. I feel sorry for these people.)

Desperate to turn the project into something worthwhile, Fisher says that Taylor invited friends to come to their house at night and suggest improvements to the script – friends like Tennessee Williams, Paddy Chayefsky, Christopher Isherwood, Joe Mankiewicz and Truman Capote, who worked for Taylor without credit as there was a writer's strike on at the time. Fisher wrote that Berman "refused to change one line of his script. 'No actors change any script of mine,' he said. He had some of the most talented scriptwriters in the world working for him – for free – and he rejected them. He just dropped their work in a wastebasket."

I have to admit a certain ambivalence about Elizabeth Taylor. I had only the vaguest idea of her career before the '70s, when she was mostly a fixture on the talk show circuit and a regular in the supermarket tabloids and celebrity mags my aunt and cousin would bring home for my mother to read. A blowsy woman in sparkly caftans with a lot of husbands and health problems and a penchant for collecting diamonds. If I encountered her at all in a film, it would be a chance viewing of something dire and inexplicable like X, Y and Zee (1972) or Secret Ceremony (1968) on the graveyard shift of late night television.

It would be years – long after seeing Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in a rep cinema, and a very abridged 16mm version of Taming of the Shrew in a grade school class – before I was aware of Liz Taylor the '50s sex symbol: the complicated, cosmopolitan brunette yin to Marilyn Monroe's sweet, vulnerable blonde yang.

O'Hara based his novel on the story of Starr Faithfull, a debutante, flapper and model who was found dead on a Long Island beach in 1931, and whose suspicious death remains unsolved. Like Faithfull, Gloria had been sexually abused by a family friend as a child, and O'Hara is unequivocal about the link between this abuse and her promiscuity – a detail retained in the movie, and whose revelation late in the story is the scene that likely got Taylor her fourth Academy Award nomination in a row.

The Code wasn't so abased in 1960 that Gloria's sexuality wasn't seen as a tragic flaw; for much of the movie the only person who doesn't call her a whore is her mother. Even Gloria calls herself "the slut of all times." (It was no wonder that Gloria takes offense at the money Liggett leaves for her. In O'Hara's novel, however, she takes it and the mink.) There might have been a few actresses who could have played Gloria (Kim Novak, Gloria Grahame, Dorothy Malone) but no one could have inhabited the part as wholly as Taylor did at that particular moment in her life, whether she liked it or not.

The script, Fisher recalled, was "just about the most exploitative story they could find. It was the story of a nymphomaniac who falls in love with a married man and almost breaks up his marriage. Hmm, now where did that concept come from? There was a line in the script where this character claims that she is sleeping her way through the alphabet college by college – and had worked her way through to Yale."

(O'Hara was obsessed with Yale, a college he didn't attend, and spent much of his career trying to persuade them to give him an honorary degree – an award they withheld because he simply wanted it too much.)

Fisher wrote in his memoir that his attraction to Taylor began while she was still married to Todd. The couple had a very earthy relationship, and Todd even brought his best man into their bedroom on their wedding night in Acapulco, showing off his near-naked bride in bed. "To me, this was Mike's way of bonding with me," recalled Fisher, "his way of proving how close we were."

His description of his ex-wife is of a woman who would say that "I think sex is absolutely gorgeous." She would regale Todd and Fisher with stories of her sexual adventures, and when Fisher finally consummated their relationship (after getting Van Cliburn to perform a private concert for her) his memories of Taylor are rhapsodic:

"Elizabeth in reality was far more than Elizabeth in my fantasies. She was a sexual being, a woman who loved sex, who loved being sexual. She was so much more than the sexual image created for her by the studio. She was uninhibited, wild, free, so totally free with her body. We couldn't get enough of each other. There had been other women with whom the physical sex had been great; other women I lusted after, and there was Debbie, but until that night I had absolutely no idea what it was like to make love to a woman with whom I was so deeply in love. Elizabeth changed everything in my life."

There were three kinds of pictures if you talked about sex in the movies at the end of the '50s. Films like BUtterfield 8 (and Peyton Place and Room at the Top and The Children's Hour) were frank, perhaps scurrilous, definitely adult. Whatever raised eyebrows or garnered column inches or got banned in Boston was in the form of words. Films that had glimpses of actual nudity – foreign ones, largely – were smut. And films that featured depictions of sex, whether real or simulated, were porn, and it would be a decade or so before Hollywood ventured into that sort of thing.

Well, technically. In his book Fisher talks about a love scene between Gloria and Steve that "ended up on the cutting room floor. It was one of the sexiest scenes ever filmed to that point and Pandro Berman insisted it be cut out of the movie."

"We actually made love on the set," Fisher writes. "I didn't have an orgasm, but we did everything else. We did it right. For the craft of acting, of course. Knowing the camera was filming us was a tremendous turn-on. We were so happy to be working together that we were giddy, like kids, and having sex on camera was the highlight."

"Elizabeth and I both hated the movie," said Fisher. "The only publicity she did for it as to tell reporters, 'I think the picture stinks.' As for my performance, she gave me a huge statue of the patron saint of actors, St. Genesius, inscribed, If you win the Academy Award before I do, I'll break your neck."

What happened next is legend. Taylor left for Europe and the title role in Cleopatra, but before filming could commence she was in the hospital for a series of illnesses that climaxed in an emergency tracheotomy in London. She recovered in time to attend the 1961 Oscar ceremony, where she was nominated for her role as Gloria Wandrous. She arrived with Fisher, in a green and white Dior gown, diamond and pearl earrings, crutches and no necklace to distract from the fresh scar on her throat. It was her fourth nomination but her first win – a consolation prize for not winning for Maggie the Cat, according to the conventional wisdom.

"It wasn't so much a victory as a coronation," Fisher recalled. "The motion picture academy honors survivors, and she was the greatest survivor of them all. It seemed obvious to me that they were going to give it to her by acclamation. This was the ultimate climax, the queen rising from her deathbed to receive the love of her court. Shirley MacLaine, nominated for her role in The Apartment, said later, 'I lost to a tracheotomy.' But it made for a legendary story."

Writing about the Taylor-Fisher marriage and this torrid thirty months of Taylor's career in Slate, Karina Longworth marvels at her acceptance speech: "I defy you to watch this and not feel like you've just been taken to school. I don't know if this is acting, or being, or what, I just know it's the purest example of stardom I've ever seen, from the greatest who ever was, and that in some sense, this moment is the final nail in the coffin of the studio system as it was."

"This officially made Elizabeth the most valuable movie star in the world," wrote Fisher, her soon-to-be-ex husband. "With all the initial problems, then Elizabeth's gallant fight for her life, and finally the Oscar, if Fox had ever harboured any doubts about going ahead with Cleopatra, they were forgotten..."

Fox would, of course, come to regret Cleopatra, as would Fisher, who would give way to Richard Burton in Taylor's gallery of husbands. The studio system, as Longworth speculated, was dead before Cleopatra drove Fox to near insolvency, and so was the Code. Elizabeth Taylor had ended the '50s as Hollywood's most notorious Jezebel, and began the '60s its biggest female star despite the epithet. Something had definitely changed.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.