If you're reading this column just after it was posted, the 91st Le Mans endurance race will be approaching its halfway point. The 24 Hours of Le Mans is one of the three most iconic car races in the world, along with the Indianapolis 500 and the Monaco Grand Prix. Twenty-two drivers have died on the track and countless injured, and over 80 spectators were killed in a single horrible day in 1955. But far, far down the balance sheet of losses at the Circuit de la Sarthe is the marriage of a major Hollywood star obsessed with the race.

"The events that were to lead to the final disintegration of my marriage to Steve might have been averted had I not come to Le Mans that summer," wrote Neile McQueen in her 1986 memoir My Husband, My Friend, a remarkably forgiving account of her years as the first wife of Steve McQueen. She made her way across the Atlantic to the filming aboard the SS France, on what was the final voyage of the grand ocean liner; the French government was no longer willing to foot the bill for its upkeep. You might have called it a bad omen.

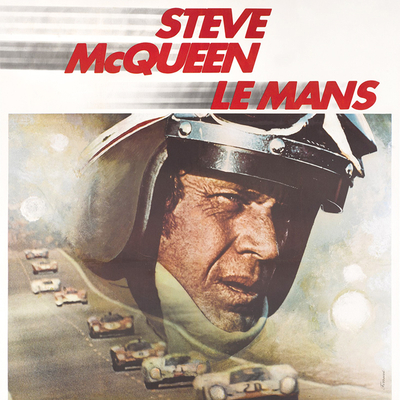

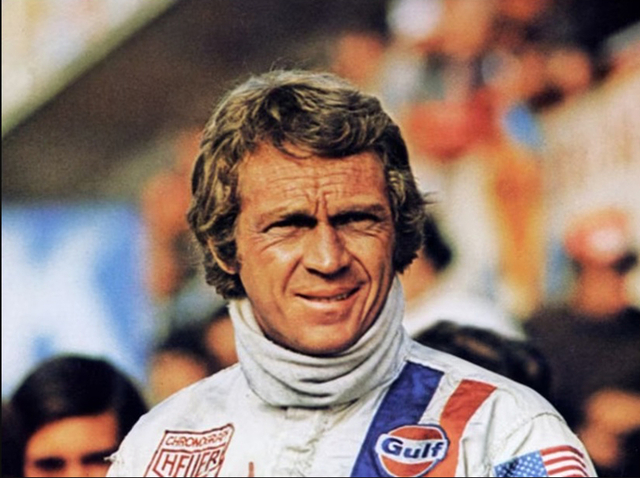

The summer of 1970 was when the actor, now the biggest movie star in the world after Bullitt, was finally able to make his passion project – the story of a driver at the famous 24-hour race. Not least among the film's many problems was that there was no actual story, but that never seemed to worry McQueen.

Le Mans begins quietly, with a long shot that picks out a brand-new Porsche 911 S driving down a country road, though keen eyes will quickly realize that the road is part of the de la Sarthe track, a nearly 14 km street circuit composed of roads open to regular traffic the rest of the year. At the wheel is Michael Delaney (McQueen), a top-ranked American driver arriving early for the race.

On his way into town he stops to stare at a conspicuously new section of guardrail by the side of the road. A series of impressionistic flashbacks rewinds to the year previous, and an accident at night between Delaney and a driver named Belgetti driving in a Ferrari that explodes in a fiery ball.

Delaney drives into Le Mans, past the ancient cathedral, and sees Lisa Belgetti (Elga Anderson), the driver's widow, buying flowers at a stall. A measured montage shows the city preparing for the race and filling up with spectators; teams ease race cars off transporters, tent cities sit waiting for occupants, merchants set up stalls and trains empty crowds onto platforms. Gendarmerie line up to receive their orders, and while rows of motorcycle cops start their bikes, one flic de moto struggles to kickstart his vehicle.

Much of what makes the 24 Hours of Le Mans such an iconic motor race is simple quantity. Its grueling continuous day-long duration, through darkness and all weather, is among the longest endurance races in the world. It also begins with a cramped field; last year's race fielded 62 cars, the most ever entered, and this year's race is scheduled to begin with the same crowded track. The winning cars cover a phenomenal distance: the record was an Audi R15+ in 2010, completing 5410 km over 397 laps. A single day at Le Mans covers more distance than a whole year's worth of Formula One races.

It also features several different classes of race cars – effectively four different races going on at the same time. There's the Le Mans Prototype classes – experimental supercars featuring leading edge technology – and the Grand Touring classes – highly modified road vehicles, both split into "professional" and "amateur" divisions, with the pro teams comprised of well-funded factory teams and "privateers": small, often shoestring operations racing for glory and the rare chance of a place on the podium next to the sponsored teams.

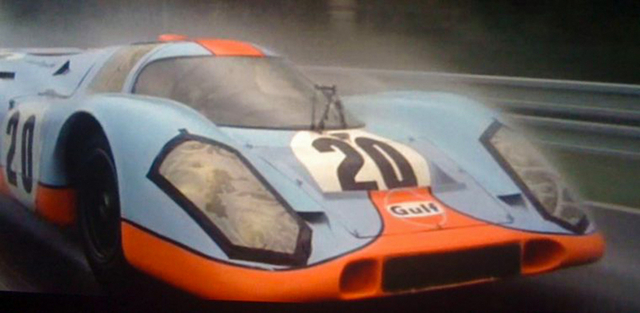

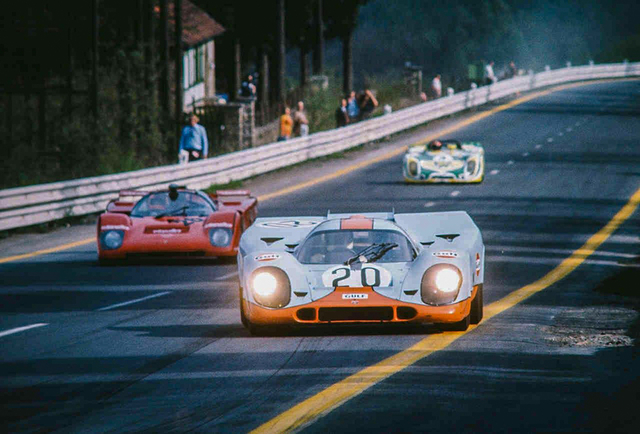

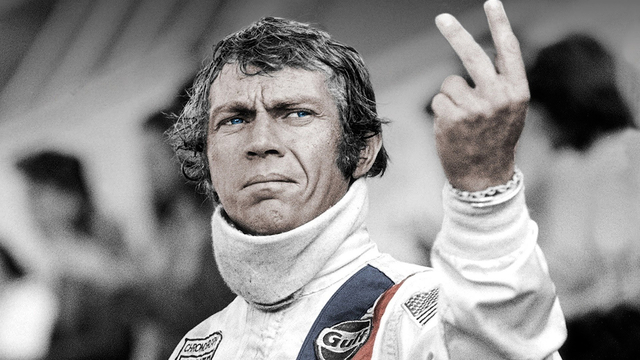

When McQueen showed up at Le Mans to play Delaney, a driver for Gulf Porsche, teams fielded pairs of drivers in two or three cars spelling each other over the 24 hours; today teams race with three drivers, and the sponsored teams – Cadillac Racing, Porsche Penske, Toyota Gazoo, Ferrari AF Corse and Peugeot Total Racing in 2023 – will usually field three cars. For manufacturers, the point of sponsorship in races like Le Mans is the old auto industry adage: "Race on Sunday, sell on Monday."

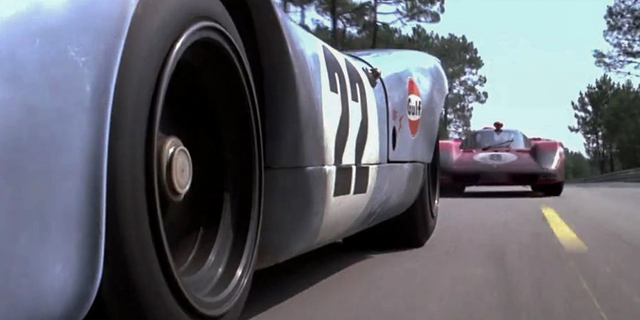

In 1970 the famous rivalry between Ford and Ferrari – fictionalized in the film Ford v Ferrari (2019) – had just ended, and the big fight at Le Mans was between Ferrari and Porsche, the German manufacturer who had finally taken the place abdicated by Mercedes-Benz after the 1955 Le Mans disaster. (Mercedes wouldn't field a team in motor racing again until 1989.)

1970 was also the first year without the famous "Le Mans start", where drivers stood across the track from their cars and ran to them when the starter's flag dropped. It was a relic from the early years of racing, and an incredibly dangerous one – it was difficult to buckle into safety belt harnesses while racing for position going into the first turns by the Dunlop bridge, and drivers would often neglect this safety measure. (One that an earlier generation of drivers had resisted, arguing that it was better to be thrown clear of a car during a crash than to burn to death in one.)

The first half hour of Le Mans is so impressionistic – that opening montage seems to last for minutes and minutes – that we suddenly find Delaney behind the wheel of his Porsche 917, eyes darting between the flag and the starting lights as the soundtrack goes silent, then mixes in a growing cacophony of heartbeat-like ticking before exploding into the race.

The original director of Le Mans was John Sturges, who had guided McQueen to stardom in The Magnificent Seven and The Great Escape. He had been involved with the project since it was called Day of the Champion but was sent into turnaround by the competing production of John Frankenheimer's Grand Prix (1966). According to Neile McQueen, "Sturges was unhappy about the absence of story. He had no desire to make a documentary even if it did feature Steve McQueen, and Steve was being stubborn in his refusal to see that a race is a race is a race."

The production was a nightmare, with or without a script; race car driver David Piper, driving a camera car built out of a Porsche 917, had a crash while filming that cost him a leg. Panic on set had Cinema Center Films, the production company, intervene to take over, and there was even talk of replacing McQueen with Robert Redford. Ultimately Sturges quit, saying he was "too old and too rich" to deal with McQueen, and was replaced with Lee H. Katzin, a director chosen by the film's producers, who had taken over creative control.

Katzin was hardly the distinguished veteran McQueen wanted for his passion project, and his resume included episodes of Bonanza, Mission: Impossible and Police Story as well as a neo-noir, What Ever Happened to Aunt Alice? (1969), the western Heaven with a Gun (1969), and The Phynx (1970), a comedy about a rock band sent on an espionage mission to Albania. Bullitt scriptwriter Alan Trustman was also fired, and whatever story Le Mans ended up telling was ultimately pulled together in the editing room.

It's hard to know what to call Le Mans. It might be as close as an American studio ever got to a European art house film at the time; perhaps it's an experimental film, or (as nearly everyone describes it) a documentary hiding under the veneer of a big-budget feature film. It really only comes alive when McQueen is in his Porsche 917, speeding past the back markers and racing against Erich Stahler (Siegfried Rauch), his new rival at Ferrari.

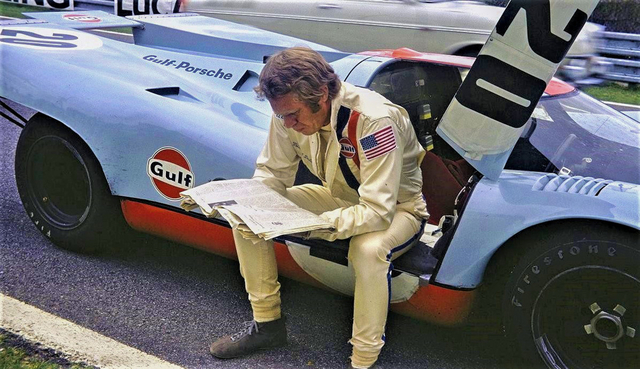

McQueen was hell-bent on capturing the look and feel of racing as experienced by drivers, and considerable time, money and talent was put into race footage. The actor considered himself as much a driver as an actor (though it's arguable that his real talent lay in off-road motorcycle racing). He had intended to enter Le Mans as a driver, hoping to share a car with the great Jackie Stewart.

But "Jackie Stewart was too sensible a man," as Neile McQueen wrote. "He didn't need McQueen...Steve was good, very good. But Steve was still an amateur who couldn't compare with the world-class grand prix drivers who did this sort of thing for a living."

"As a matter of fact, Jackie Stewart was heard to remark that he disliked racing at Le Mans because there generally were too many amateur drivers behind those powerful cars."

Instead McQueen modified the Porsche 908/2 he had co-driven to a second-place finish at the 12 Hours of Sebring with millionaire gentleman driver Peter Revson (beaten by none other than Mario Andretti) and entered it in Le Mans as a camera car, where Porsche drivers Herbert Linge and Jonathan Williams raced it 282 laps to a 9th place finish, second in its class despite frequent stops to change film.

But the script – if there ever was one – is merely a notion; the dialogue for the whole film could fit onto a few index cards, and the first real lines spoken between two characters aren't heard until nearly forty minutes into the picture. McQueen famously hated talking as opposed to doing, but anyone who paid a ticket expecting to see McQueen defy authority, get into punch-ups or get the girl was still disappointed.

The height of the film's action occurs halfway into the race, during the long stretch between sunset and sunrise, when Stahler, Delaney and his Porsche teammate Claude Aurac (Luc Merenda) get into a major incident at Indianapolis corner. Stahler spins his Ferrari, which sends Aurac off track, crashing his car through a billboard, escaping the wreck just before it explodes. Distracted by the burst of flames out of the corner of his eye – an echo of the crash that killed Belgetti the previous year – he loses control trying to avoid a back marker and totals his Porsche.

Motorsport was at its most dangerous when Le Mans was made. The '50s and the '60s were the bloodiest for the sport, with well over a hundred fatalities every year, 1955 being the worst thanks to the Le Mans disaster. Jackie Ickx helped put an end to the "Le Mans start" by pointedly walking across the track to his car in 1969, just before driver John Woolfe was killed in a crash during the first lap after being unable to put on his safety belt. (Ickx drives one of the cars in Le Mans. He would win the race six times, three of those with co-driver Derek Bell, who also drove a car in the film.)

Jackie Stewart would spend much of his career agitating for increased safety standards, retiring suddenly before the 1973 season was over and missing his 100th grand prix after the death of teammate François Cevert during practice for the US Grand Prix. (Ironically, Ickx would often oppose Stewart's efforts, claiming that safeguards and regulations took the challenge out of the sport.)

The scenes away from the racetrack are the film's calmest, following McQueen's Delaney on breaks from the car as he wanders from the pits to his trailer to the driver hospitality area. It's where he constantly encounters Lisa Belgetti, whose presence is meant to haunt the other drivers and elicit feelings of guilt in Delaney.

He sits next to her in the commissary, gently inquiring how she's doing but wondering why, exactly, she wants to be there. Later, after his crash, she sits with him in his trailer and they talk about the danger of being a driver. "This is a professional bloodsport," he tells her, before uttering the film's trademark line:

"Racing is life. Anything before or after is just waiting."

There's a long sequence where, while the drivers are risking their lives on the track, the camera wanders among the crowds attending the race. They nap in the bleachers or on the grass; they eat while children play on the rides in the amusement park behind the grandstand or race go-karts just a few yards away from the real racetrack. Young people neck; a fat man wears a funny hat; a stout middle aged woman sits on a folding chair smoking a cigarette. Most of them look either bored or oblivious while men like Delaney and Stahler risk their lives to entertain them.

Le Mans on the whole takes a far more fatalistic attitude to the risk and dangers of motorsport than the melodramatic Grand Prix five years earlier, where Eva Marie Saint holds up her hands, covered with the blood of her dead racing driver lover, angrily asking the mob of press and photographers "Is this what you want?"

Early in the film we're introduced to Ritter (Fred Haltiner), one of Delaney's teammates, a veteran driver with a wife and children, planning on retiring. This seems to mark him as the film's likely fatality, but after Delaney's crash sets Gulf Porsche back one car, he's taken out of the race by the team manager Townsend (Ronald Leigh-Hunt) for being too slow and his place is given to Delaney, who's ordered to "drive flat out. I want Porsche to win Le Mans."

After a tense battle between the last two Porsches and Stahler's Ferrari – magnificently shot with cameras on mechanized swinging arms attached to the bumpers of the cars – Delaney's teammate takes the chequered flag. But back in the early '70s there was no crowded podium and second place was still first loser. Catching each other's eyes while the crowd surges past them in pit lane, the two rivals stare each other down before Delaney flips the bird at Stahler and grins.

It would become one of McQueen's most iconic moments onscreen, but the film was a flop, bankrupting his company, Solar Productions. The filming had also seen the end of his marriage, which effectively ended one night in Le Mans when he pulled a gun on Neile in their bedroom, while violently interrogating her about her brief affair with Maximilian Schell. (McQueen famously slept with everyone from co-stars to groupies to hitchhikers but refused to see the double standard. Nobody writing about this period in his life can depict the actor as anything less than contemptible.)

She discovered she was pregnant with McQueen's child while still in Europe but went to have an abortion in London. Still, Neile encouraged him to read two books that had been optioned for filming, and his '70s comeback in The Getaway and Papillon was largely thanks to his soon-to-be ex-wife.

"However thrilling the documentary footage," writes Christopher Sandford in McQueen: The Biography, "Le Mans' fictional story never quite got out of first gear. The result was much like a minor Kubrick film, elegant and somehow empty and pedantic, all style and precious little content except that which was tediously precious itself."

Time called it "hollow." Rolling Stone called it "shit." He would never lose his love of cars and bikes, but Le Mans would be the end of his racing career. Ironically, On Any Sunday, a low-budget documentary about motorcycle and dirt bike racing featuring McQueen that Solar made while he was in pre-production for Le Mans was praised as one of the greatest motorsport films ever when it was released the same year.

Solar might be bankrupt and his marriage over, but McQueen was still a major star heading into the last decade of his life. Le Mans made its budget back handily thanks to foreign sales and with time became a cult classic, especially among motorsport fans who were more than happy to watch, over and over, a film that was light on story and heavy on racing. Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans, a documentary about the making of the film featuring outtakes and "lost" rushes as well as interviews with Neile McQueen, Derek Bell, Jonathan Williams and David Piper as well as McQueen's son Chad, was released in 2015, almost forty-five years after the film's release.

Le Mans certainly never stopped anyone from trying to make the ultimate racing film. There have been decent efforts (Rush (2013) and Ford v Ferrari) and duds (Driven (2001), Speed Racer (2008) and Days of Thunder (1990)) as well as good-natured goofs (Talladega Nights (2006)).

Gran Turismo, a feature about the true story of Jann Mardenborough, a gamer who won a seat at Le Mans in 2013, is due for release this summer. And the surge in interest in Formula One thanks to Netflix' documentary series Drive to Survive has inspired an as-yet-untitled Brad Pitt picture to start production, with the actor scheduled to outdo McQueen and appear on the grid in a car at the British Grand Prix at Silverstone next month.

But this racing fan will always have a soft spot for a film where its egomaniac star took pains to make sure the right engine noise was mixed into the soundtrack when different cars roared past the camera or fought to pass each other. McQueen might have ruined his marriage and let down his fans but he wrote a love letter to motorsport that only gearheads can truly appreciate.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.