While we often think of nostalgia as an emotion that helps shape our memories or a longing for the past; a romantic feeling, it has to be remembered that nostalgia was once regarded, like melancholy, as a kind of mental illness, sometimes considered fatal in soldiers and sailors kept away from their homes for too long.

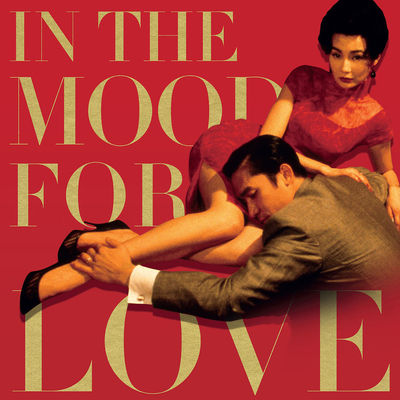

Director Wong Kar-wai, talking about his 2000 film In the Mood for Love – regarded today as his masterpiece – said that "the film is about a period that's been lost and actually is like a dream." The specific period he was talking about was Hong Kong in the early '60s, the city his parents moved to when he was five, escaping the turmoil threatening Shanghai with the first stirrings of Mao's Cultural Revolution.

Working with his cinematographer Christopher Doyle over an astonishingly long 15-month shoot (which Doyle had to leave, leaving Mark Lee Ping-bing to finish the film), Wong strove to find and capture what was left of the Hong Kong of his childhood while the city transformed itself at its customary breakneck pace around him. In an interview with the New York Times, the director said that "I always wanted to put someplace in my films, a corridor, a restaurant or a street, because I knew it would be gone soon. Things change so fast here."

Summed up very crudely, In the Mood for Love is a remake of David Lean's 1945 romantic drama Brief Encounter. In 1962 Hong Kong two young couples who've moved to the city from Shanghai end up renting rooms in adjacent apartments owned by two older couples. Mr. Chow (Tony Leung) works for a newspaper while Mrs. Chan (Maggie Cheung) is secretary to the owner of a shipping company.

We never meet their respective spouses, or at least we never see their faces. Except for a handful of older characters – their landlords Mr. Koo and Mrs. Suen, her boss, his co-workers – Wong's film quickly and obsessively focuses in on Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan to the exclusion of anyone else as they discover that their spouses have begun an affair.

In the cramped hurly-burly of Hong Kong affairs are just one way people amuse themselves; Mrs. Chan's duties at work include helping her boss organize the logistics of juggling his wife and his mistress, while at work Mr. Chow has to loan money to his co-worker Ping (Siu Ping Lam) when he falls behind on his tab at the brothel.

Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan are drawn together by their spouses' betrayal, and the first thing they do is try to understand how it could have happened. Meeting in restaurants and in alleyways they act out potential scenarios, critiquing each other on the plausibility of their performance as their cheating spouses. They know they're playing a dangerous game but insist that "we won't be like them."

Wong Kar-wai began his career writing for television before moving on to movies, working with and without credit on pictures made while Hong Kong's film industry was near its commercial zenith. When he started making his own movies, starting with the crime drama As Tears Go By (1988), he quickly became one of the few bright lights in Hong Kong's declining movie scene, with films like Days of Being Wild (1990), Chungking Express and Ashes of Time (1994), Fallen Angels (1995) and Happy Together (1997).

His films were dynamic and wildly stylish; working with Doyle he brought the vivid colour palette and brash design of the '80s forward into a new decade by combining it with the mood and experimentation of Europe's various new waves. I remember watching most of Wong's early films at a retrospective in the late '90s and being ashamed that I had somehow overlooked such a monstrous talent working in plain sight.

It also has to be understood that all of these films were made during the run-up to the 1997 handover of Hong Kong to China by Britain – an agreement signed in 1984 by Margaret Thatcher and Deng Xiaoping. It was one of two deadlines that would loom over Hong Kong, the other being 2047, when China is set to end the "one country, two systems" administration of Hong Kong, though the protests, riots, crackdowns and arrests of the last two or three years have shown that Xi Jinping's regime in Beijing has every intention of moving up that timetable sharply.

When Wong made In the Mood for Love the anxiety infusing Hong Kong society had hardly diminished – a reasonable reaction, it turned out, and the director responded by eulogizing the city he grew up in as a shabby but beautiful, fallen urban Eden. It was a feeling widely shared by the city's residents, past and present; the work of photographer Fan Ho, a former actor and director in Hong Kong who emigrated to California in 1979, was serendipitously rediscovered around the same time.

Far more austere than Wong's films, Ho's luminous black and white street photography of Hong Kong in the '50s and '60s is just as stylish as Wong's work, capturing a city of deep shadows, where shafts of sunlight pick out scenes suggesting an epic film noir. The younger director had apparently set to work capturing the final traces of the world the older man had witnessed so vividly.

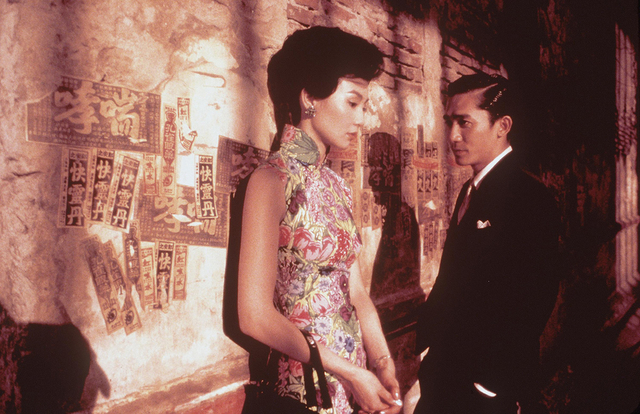

The city that forces Mrs. Chan and Mr. Chow together to poke at the wounds of infidelity is a cramped one, built vertically, with apartments, offices and hotel rooms piled on top of each other while shops and restaurants fill the streets and basements. Space is at a premium and living space scarce; sunlight barely makes it down to the windows and shift work and overtime is rampant – anything to avoid heading home to the crowded flats shared by family and strangers.

In these tight spaces everyone is forced to hug the walls to pass each other, and conversations take place deep within their comfort zones. This does a lot to amplify the erotic charge between Mrs. Chan and Mr. Chow, even before they're forced into an emotional intimacy they might otherwise have avoided.

"You notice things if you pay attention," Mrs. Chan tells her boss, who has to be careful what tie he wears and what gifts he gives when he's with either his wife or his mistress. Ties and purses provide the clues that make her and Mr. Chow discover their mutual betrayal, but even before they confront the sordid truth we've already been made to feel that we're up close and personal with them in the same rooms, feasting on all the period details that Wong and Doyle stuff into each frame.

As I wrote about the tentative romance between Alain Delon and Monica Vitti at the heart of Michelangelo Antonioni's L'Eclisse (a film I can't help but imagine Wong had among his influences for this picture), much of the dramatic tension propelling Mrs. Chan and Mr. Chow toward each other is the fact that they are, by any measurement you might choose, by far the most attractive people in the film.

Tony Leung is a major star in China and Asia in general, with starring roles not just in many of Wong's films but in movies by John Woo (Hard Boiled, Red Cliff), Zhang Yimou (Hero), Ang Lee (Lust, Caution) and Hou Hsiao-hsien (A City of Sadness). He was a successful pop singer in the '90s before leaving music for acting, and he and his wife, actress Carina Lau, are one of Hong Kong's major celebrity couples.

Wong said that Leung's Mr. Chow was meant to echo Jimmy Stewart in Vertigo – a dark and obsessive character made much less sinister by the actor's persona. "Just imagine if it was John Malkovich playing this role," he told LA Weekly in 2011. "You would think, 'This guy is really weird.' It's the same in Vertigo. Everybody thinks James Stewart is a nice guy, so nobody thinks that his character is actually very sick."

Maggie Cheung, Toronto, 2000; Tony Leung, Toronto, 2007. Photos by Rick McGinnis |

Maggie Cheung, also once a regular in Wong's films, was probably the biggest female star in Hong Kong cinema when she made In the Mood for Love. (I photographed her at the film festival when the film debuted in Toronto; I had to convince my editors to put her on the cover of the paper – a gamble that paid off when the issue disappeared from the newsstands in a couple of hours, mostly thanks to the city's huge Chinese community.)

Cheung's Mrs. Chan is the focus of much of Wong and Doyle's effort in the film. A startlingly beautiful woman – a former model and beauty queen and, like so many Chinese movie stars, a pop idol – she's the focal point of nearly every scene, in figure-hugging cheongsam dresses and elaborately crafted up-dos.

To create Cheung's wardrobe Wong and his production crew went to Long Kong Ladies, a venerable dressmaking shop in Hong Kong's Causeway Bay, where Master Leung Long Kong had been sewing cheongsams or qipaos since the '60s. He recreated the uniquely tight, high-collared qipaos of the era using vintage and new dresses; his work would have sold for around $100 at the time, but in 2000 they went for twenty-five times as much and ended up causing a sensation in the fashion industry.

Similarly, Wong went to another holdout from Hong Kong's past, Yang Tze Beauty Parlour in Happy Valley, to create Cheung's elaborate up-dos. Hairstyles from the time were grouped according to clientele dubbed "Young Ladies," "Rich Ladies" and "Mature Ladies," and had names like "Dragon and Phoenix," "Cocktail" and "Butterfly".

The result is that Cheung suffers as beautifully in front of Wong's camera as Celia Johnson did for David Lean. Mrs. Chan and Mr. Chow – a pair but not a couple – are drawn together, first with their masochistic game imagining the genesis of their betrayal, and eventually by the aching mutual attraction that was always inevitable.

Their suffering is intensified by the certainty that while their spouses are enjoying their affair far away from prying eyes, they (like Johnson and Trevor Howard in Brief Encounter) have to be discreet to avoid the censure of the eyes that are on them at all times. After Mrs. Chan gets a warning from Mrs. Suen, her landlady, that her late hours have been noticed – her husband's frequent absences are apparently overlooked – the two of them are forced to hide in Mr. Chow's room for nearly two days when the Koos and the Suens arrive home early and begin a marathon mah-jong session.

Another element of the picture that poignantly and painfully amplifies the mood is the music. It goes without saying that life in a city like Hong Kong would be full of unwanted odours and sounds, and while there's no way to evoke smells except with frequent shots of steaming pots and shared meals (one potential title for the film was A Story of Food), the soundtrack is full of snippets of music, from Chinese opera to vintage Cantonese pop.

Above that, though, is theme music like "Yumeji's Theme", a tentative melody of plucked strings borrowed from Shigeru Umebayashi's score for Seijun Suzuki's Yumeji – a delicate and elegant tune that acts as Cheung's motif for the film.

The two discarded spouses, however, have their hours together scored by three of Nat King Cole's halting, crepuscular covers of Latin American standards – "Aquellos Ojos Verdes", "Te Quiero Dijiste" and best of all "Quizás, Quizás, Quizás", which Desi Arnaz had recorded (in English) in 1948.

The film's final act is, like Brief Encounter, a series of missed connections. Mr. Chow is reassigned to Singapore but leaves alone when Mrs. Chan doesn't meet him at his hotel. The film jumps ahead to 1966 and another period of heightened tension in Hong Kong. (Riots would break out in the city a year later) Hong Kong has been a refuge for people escaping famine, war and turmoil in the north for centuries, but trouble is always just over the hills.

Mrs. Chan and Mr. Chow return separately to their old flats to discover Mrs. Suen preparing to move to America where her daughter lives, while the Koos have already left for the Philippines. Mr. Chow is told that a woman is living with her son in the Suen's old apartment. A year later Mr. Chow is in Cambodia covering a state visit of General De Gaulle with Prince Sihanouk. He visits the temple ruins at Angkor Wat still carrying his secret.

In the Mood for Love was a critical sensation when it was released, winning awards for Leung and Doyle at the Cannes film festival, along with prizes in Hong Kong, France, Germany, Belgium and at the BAFTAs and the New York Film Critics Circle awards. It frequently places on best film lists, and Sofia Coppola said it was a huge influence on her Oscar-winning Lost in Translation (2003).

Both Christopher Doyle and Maggie Cheung would stop working with Wong, citing his intense working methods and his largely scriptless shoots. (Wong was apparently editing In the Mood for Love up until a day before its Cannes debut.) Cheung retired from acting in 2004 to start a career as a composer.

Wong would make a sequel of sorts to In the Mood for Love in 2004 with 2046, the title a reference to the end of China's "one country, two systems" agreement. I've heard it's interesting – it's hard to imagine the director making anything less than fascinating – but I consider In the Mood for Love so nearly perfect, at least visually, that I haven't been able to bring myself to seek it out. Every time I've watched the film their chaste romance has been even more affecting; knowing what, if anything, happens next would ruin one of the most richly created moods ever put on film and decimate my nostalgia for its beautiful, impossible world.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.