It's fun and easy to make fun of Hollywood's creative bankruptcy these days, and its reliance on remakes and reboots and retellings of stories it's told many times before. There are, however, some stories worth remaking; Roland Emmerich's recent Midway (2019) was as strident and bombastic as anything made by Michael Bay, but at least it put the 1976 film of the same name, a star-studded but tedious Sensurround epic, deep in the shadows where it belongs.

Like sci-fi, war films are the major beneficiaries of the digital effects revolution. Some taste and restraint are needed, of course, though they're often in short supply; Russia in particular has recently produced dozens of war films (White Tiger, T-34, Tankers, Stalingrad, The Pilot), usually with scripts of a much lower priority to the filmmakers than increasingly outlandish and improbable visual effects – tank shells in Russian pictures travel in slow motion, the camera trailing and spinning around them as they create outsized damage with impossible accuracy.

But when I see the quality and technical sophistication of films like Dunkirk (2017) and 1917 (2019), I can't help but hope that someday someone will take another shot at the story of the Bismarck, the leviathan German battleship that was the most feared ship on the ocean during the early days of World War 2, albeit only for the eight days of her first and only voyage. There is, of course, a perfectly serviceable film about the Bismarck available on streaming services and disc, but to modern eyes it looks like a relic from the days of model boats filmed in swimming pools.

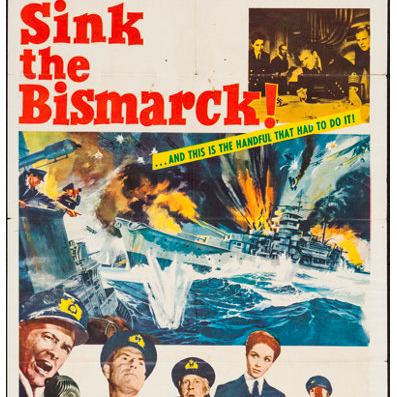

Sink the Bismarck! was released in 1960, based on C.S. Forester's Hunting the Bismarck, published just the year before. Despite being filmed in the UK with a British cast and looking as if it should be a product of Ealing, Rank or Associated British Pictures, it was technically a Hollywood product, made by 20th Century Fox.

The British film industry and its directors had their biggest successes with war films in the '50s – movies like The Cruel Sea (1953), The Dam Busters (1955), Reach for the Sky (1956), Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) and Ice Cold in Alex (1958). Veterans and people who'd lived through the war made up an appreciable majority of cinemagoers, and there was an appetite for war stories with appropriately heroic themes, though not without occasional explorations of moral ambiguity.

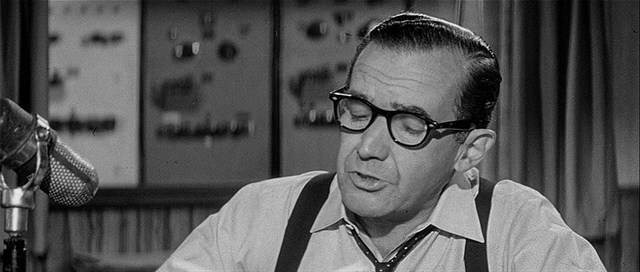

The film begins with a Nazi newsreel – or director Lewis Gilbert's recreation of one – with the usual strident German narrator extolling the magnificent new battleship being launched in 1939 with Hitler himself in attendance at the Blohm & Voss shipyards in Hamburg. The film cuts to two years later and London during the Blitz, with Edward R. Murrow himself reprising his role as the preeminent American journalist on the ground there, broadcasting the story of Britain alone against the Axis powers.

While Murrow sets the expository scene, we watch a man in a Royal Navy uniform walking alone through Trafalgar Square on his way to Admiralty House and its underground war room. Captain Jonathan Shepard (Kenneth More) is the new head of the navy's operations division, a not wholly desired promotion to an important staff job after having his cruiser sunk from underneath him in Norway the previous year.

More was the most British of actors; he'd portrayed Group Captain Douglas Bader in Gilbert's Reach for the Sky, and was a Royal Navy veteran who starred in films like Doctor in the House, The Deep Blue Sea, A Night to Remember, The Greengage Summer, The Longest Day and The Battle of Britain. He was an actor used to embodying British virtues, and his fictional Shepard is a solid stiff upper lip whose first act of business is to crack down on the laxities and uniform violations that have crept into the Admiralty after nearly two years of war.

He places two framed pictures on his desk: the ship he lost and his son, serving as an air gunner on the aircraft carrier Ark Royal. He's admired by his superior officers but does nothing to solicit affection from his subordinates, most notably WRNS Second Officer Anne Davis (Dana Wynter), introduced to Shepard by his outgoing predecessor as the very capable glue holding the Operations Room together.

Wynter was a stunning woman, born in Germany and raised in the UK and South Africa. She had begun her career with small roles in British films, with credits like "Baron Gruda's traveling companion" in The Crimson Pirate (1952) or "Morgan Le Fay's servant" in Knights of the Round Table (1953). She was signed to a Fox contract in 1955 and played the role she remains famous for in a very American movie – Becky in Don Siegel's sci-fi paranoia classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) – alongside major parts in war films like D-Day the Sixth of June (1956, and probably among the worst D-Day pictures ever) and the melodramatic Fräulein (1958).

Wynter was one of those British actresses, like Barbara Shelley, Glynis Johns, Joan Greenwood and Valerie Hobson, who could make pre-Swinging London poshness seem sexy, and on her the already flattering WRNS uniform looks even better. Her Officer Davis emotionally tempers the upright Shepard; their slow-burning, barely perceptible romance is supposed to be the emotional anchor of the very large part of the film that happens far from the open sea, in the Admiralty's underground war rooms – a curious dramatic choice that renders Gilbert's picture more than a bit stiff and inert, like setting most of a movie about the battle of Stalingrad in Stalin's dacha.

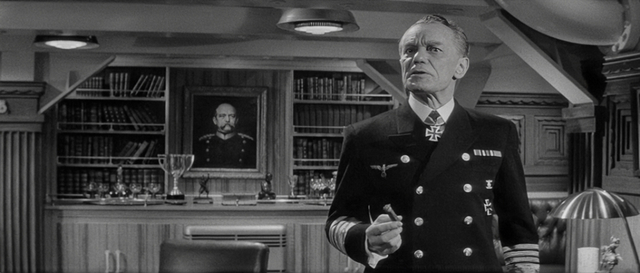

On the Bismarck we meet the movie's heavy – Admiral Günther Lütjens, in charge of the task force sending the brand-new battleship and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen out into the North Atlantic sea lanes to sink crucial convoys on their way to Britain. In Gilbert's movie – as opposed to what we know about the man in real life – he's a fanatic Nazi, in thrall to Adolf Hitler, who he credits for rescuing his career from Weimar obscurity when he took over the country and revived its military.

Gilbert introduces Lütjens (played by Czech actor Karel Štěpánek) like a Bond villain – shot from behind in his cabin aboard the Bismarck, wreathed in smoke before he muses about the "chess game" they're about to play with the British Navy. He constantly upstages Lindemann (Carl Möhner) the battleship's captain, to give orders over the ship's speakers or deliver rousing speeches about how "we are faster, we are unsinkable, and we are German!" Besides being an ardent Nazi (in contrast to the humbler Lindemann, who's portrayed as more loyal to his men than the mission), his vainglory and arrogance would be bad omens even if we didn't know how this story ends.

There was a time when the story of the Bismarck loomed large in the imaginations of the public, and young boys in particular. Perhaps it was better known in Britain and Commonwealth countries like Canada, though the same year the film hit theatres country singer Johnny Horton released "Sink the Bismarck", a folksy anthem in march tempo in the same vein as his 1958 hit "The Battle of New Orleans":

We'll find the German battleship that's makin' such a fuss

We gotta sink the Bismarck cause the world depends on us

Hit the decks a-runnin' boys and spin those guns around

When we find the Bismarck we gotta cut her down

The song was actually commissioned by Fox, who were worried that US audiences wouldn't remember the Bismark (sic) as well as they did Pearl Harbor, and while the song isn't on the film's soundtrack, it was featured in US trailers for the picture. I remember both of Horton's historical hits thanks to the looseness of AM radio when I was young, before Top 40 playlists were centrally planned and relentlessly enforced and oldies still made up much of non-peak airtime, mixing in hits from the '50s and '60s like Horton's with the latest from David Bowie, America and Grand Funk Railroad.

I saw Gilbert's film the first time on TV, on some weekend afternoon outside prime time, and I even had the Airfix model of the battleship – a challenging one to assemble, so much that I never got around to painting it after the glue dried.

There are two dramatic high points in the story of the Bismarck: the first is the sinking of the HMS Hood during the first exchange of gunfire between the Home Fleet and Lütjens' task force, the second the sinking of the Bismarck itself, a much more drawn-out battle that came at the climax of days of missed communications, intelligence errors, near misses and high seas cat and mouse games in bad weather.

There's real tragedy at the heart of the story of the Hood. The ship was the public face of the British Navy, the "Mighty Hood", a Royal Navy flagship, but she was actually a relic when she sailed from Scapa Flow to intercept the Bismarck. The Hood was a battlecruiser, not a battleship, laid down during World War 1 and commissioned less than two years after the war ended.

In Bismarck: The Final Days of Germany's Greatest Battleship, Niklas Zetterling sums up the career of the Hood, which after the Armistice was the largest warship in the world, and the most obvious candidate to spearhead British gunboat diplomacy. She circumnavigated the globe starting in 1923, a year-long voyage that stopped in Sierra Leone, Cape Town, Zanzibar, Ceylon, Singapore, Fremantle, Adelaide, Melbourne, Hobart, Sydney, Wellington, Auckland, Fiji, Samoa, Hawaii, San Francisco, the Panama Canal, Jamaica and Canada. She was the site of a mutiny, attempted (but failed) to halt Mussolini's invasion of Ethiopia, and escorted British merchant ships through Franco's blockades during the Spanish Civil War.

"During this period," Zetterling writes, "it became increasingly clear that the Hood, after almost two decades of service, needed extensive rebuilding and modernizing, requiring quite some time in a shipyard." But that upgrade never happened, and when the Hood sailed out to meet the Bismarck she was essentially unfit for purpose.

Her greatest weakness was one that British cruisers were known to have since the Battle of Jutland – weak deck armour that provided no protection from the plunging shells that a ship like the Bismarck was designed to send her way. Until this point the only real battle the Hood had seen was shelling the French navy at anchor in Oran to prevent it being used by the Germans.

"Engaging the Bismarck," writes Zetterling, "would be something quite different." And so, minutes after battle was joined between the two German ships and the Hood and the Prince of Wales, a shell hit home and basically blew the Hood apart.

In Sink the Bismarck! this catastrophic moment is treated reverentially, almost a moment of silence as Admiral Holland (Walter Hudd) and his men on the bridge of his flagship brace expectantly for the German salvo to land. We see a scale model of the Hood blow up with the kind of out-of-scale explosions that surely make modern audiences wince, before the camera cuts to the reactions from both sides.

Only three of over 1,400 crew on the Hood survived, one of them signalman Ted Briggs, who died in 2008. Briggs' memories of the Hood are the most vivid accounts of the ship's sinking, and Zetterling quotes them extensively, including how, while searching for a way out of the destroyed ship, Briggs "took a glance into the bridge and saw Holland sitting huddled up in his seat, resigned about the fate engulfing them all. The defeated admiral was the last person seen by Briggs, before ice cold water surrounded him and pulled him down into the bubbling depths of the ocean."

Everyone who witnessed the explosion that sunk the Hood described it differently, from "an enormous blowtorch" to "a long pale red tongue of fire" to "a sea of fire shaped like a fan or an inverted cone." Briggs recounted his fight to survive as the suction from the Hood's sinking pulled him under:

"I struggled madly to try to heave myself up to the surface. I got nowhere...My lungs were bursting. I knew that I just had to breathe. I opened my lips and gulped in a mouthful of water. My tongue was forced to the back of my throat. I was not going to reach the surface. I was going to die. I was going to die...I had heard that it was nice to drown. I stopped trying to swim upwards. The water was a peaceful cradle. I was being rocked off to sleep. There was nothing I could do about it – goodnight, mum. Now I lay me down...I was ready to meet my God."

Sink the Bismarck! was made just as most of the WW2-vintage ships that survived the war were destined for the breaker's yard, so Lewis Gilbert was able to use decommissioned boats in Portsmouth harbour to film the explosions and mayhem of the battle. The HMS Vanguard, the last British battleship in service and due to be scrapped, stood in for the Hood, Prince of Wales King George V and Bismarck, while the HMS Belfast (now a museum ship in the Thames) subbed for the British cruisers at the battle. The aircraft carrier Victorious, which sent off the first torpedo planes to attack the Bismarck, played herself and the Ark Royal, and three vintage Fairey Swordfish biplanes were restored for filming, and still fly as part of the Royal Navy Historic Flight.

But there were no surplus battleships that could be blown up and sunk twice, so veteran model-making specialists like Bill Warrington, L.B. Abbott and Howard Lydecker were hired to build and film the models in a tank built at Pinewood studios. Aficionados of model ships in movies have nothing but praise for their work on Sink the Bismarck!, but the test of time and the advent of digital filmmaking have made these quality practical effects look as dated as iris-outs and shuddering camera dollies.

Except for Štěpánek's increasingly unhinged portrayal of Lütjens, the restraint and Britishness of the film is also miles away from the broad strokes used in most war films today. Back at the Admiralty, Shepard discusses why he thinks emotions need to be rationed in wartime, in a scene where he and Davis compare their personal losses – his wife to a German bomb, her fiancée at Dunkirk.

He fights to keep calm with the news that his son's plane has gone missing; when he receives news that he was rescued after ditching, More retreats to the furthest corner of his office to let out several heaving sobs; in the film's arid emotional setting (director Gilbert liked to describe it as "a detective story set at sea") they're as shocking as the sinking of the Hood.

The Bismarck's end, when it inevitably comes, is a death by a thousand cuts. As soon as the extent of the damage from a torpedo attack revealed that the ship had lost the ability to steer, the mood had gone from triumph to despair. When the attack finally begins it quickly devolves into a turkey shoot, and Zetterling's book describes how a Corporal Herzog was ordered below decks after his anti-aircraft battery was destroyed:

"Herzog went to his closet, where he allowed himself a few nips of liqueur. Then he lay down in his hammock and listened to the battle. It was not long before he felt drowsy. Vaguely he heard the loudspeakers announce that Lütjens and Lindemann had been killed. Somewhat later, it was denied that Lindemann had been killed. The message was followed by a loud crash not far away, soon accompanied by the screams of the wounded. All of this happened as Herzog was half sleeping in his hammock. The battle indeed appeared unreal."

Shell blasts either killed sailors outright or rendered them punch-drunk from concussion and blast effects – if the hail of splinters and debris didn't cut them apart. One survivor saw two Luftwaffe warrant officers assigned to the ship shoot themselves at the same time to escape drowning. Donald Campbell, a lieutenant on HMS Rodney, exclaimed "Good God – why don't we stop?"

Not long after this the order was given to cease firing, and after capsizing Zetterling writes that the Bismarck "finally hit a volcano on the bottom of the ocean, almost five kilometres below the place where she had fought her last battle. She slid along the mountain slope before she settled in the sludge where she was to remain indefinitely."

In Gilbert's film Shepard dictates an order requesting Officer Davis' presence for dinner, but when they emerge from the Admiralty building they discover it's morning, and as the final credits roll the two head off through Trafalgar Square to breakfast. Nudge nudge wink wink.

Sink the Bismarck! was a hit, and while it was expected to launch More to the next stage of his career, he proceeded to tear into his boss John Davis, the head of Rank, while drunk at a public event. Davis blocked the loan of More to Columbia for The Guns of Navarone, for the role that went to David Niven, and the outburst effectively blacklisted More.

Dana Wynter's career didn't thrive after the film either, and most of her career in the '60s and '70s would be on television, including the inevitable appearances on Love Boat and Fantasy Island. Lewis Gilbert did much better, going on to direct Alfie (1966), Educating Rita (1983) and three Bond films (You Only Live Twice, The Spy Who Love Me and Moonraker.) He died at home in Monaco in 2018.

In the meantime there hasn't been a big budget attempt to re-tell the story of the Bismarck in over sixty years. And while technology has certainly surpassed our expectations of what can be shown onscreen, I live in hope that some truly talented director on the level of a Denis Villeneuve or Christopher Nolan might break the action movie template and zoom in on the stories of men like Briggs and Herzog – moments of fear and chaos and surreal awe that mark and traumatize survivors. Until then it remains the better movie I can watch in my head.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.