The unenviable task of sharing the screen with Burt Lancaster fell to Ossie Davis in The Scalphunters, a 1968 western about a trapper and an escaped slave forced together in the southwestern desert just before the Civil War. Davis, thankfully, was up to the task, in what the marketing department at United Artists might have promoted as a buddy film in a subsequent decade, when Davis would have been co-billed alongside Lancaster instead of being bumped to fourth on the poster behind Shelley Winters and Telly Savalas.

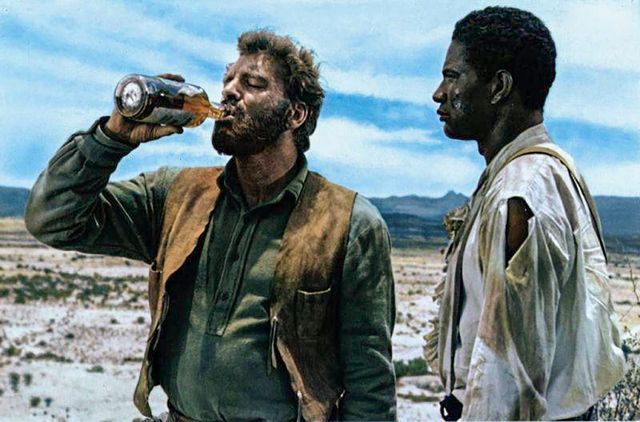

The simple fact was that Burt Lancaster didn't really share the screen as much as dominate it, and almost anyone stuck in the frame with him tended to become a background character. Davis, by then a veteran actor and playwright, figured out the trick that would let him hold his own alongside Lancaster in Sydney Pollack's widescreen western, and in an interview with Roger Ebert around the time the film was released he noted that "there is a scene in which Lancaster rides and I walk – so what? In the end I get what I'm after. And so does Lancaster."

"No matter how much suspicion we feel at the beginning of the picture, by the end we're brought together by sheer self interest. We're partners because it makes sense.

"And that," Ossie Davis said, "is what it's all about."

Who rides and who walks were loaded questions in 1968, and everyone working on the project – including Pollack and the hardcore Hollywood liberal Burt Lancaster, who co-produced the film, and certainly Davis, an outspoken civil rights activist – were careful to come up with what seemed like a satisfactory answer, at least for 1968.

The film begins with Joe Bass (Lancaster), a trapper making his way back to civilization after a season in the wilderness with a load of furs on the back of his pack horse. He's intercepted by a group of Kiowas led by Two Crows (Armando Silvestre) who could simply take his furs but try to make the exchange amenable to Bass by offering him Joseph Lee (Davis) in trade – an escaped slave they had taken from some Comanches.

Lee was on his way to Mexico and freedom when the Comanches intercepted him, a house servant who can read and write, unlike the illiterate Bass. (How Lee, who escaped from a plantation in Louisiana, ended up in what one presumes in the New Mexico Territory on his way to Mexico suggests a whole other movie – and one that might have been worth seeing.) Lee says he liked the Comanches and would be happier back in their company than either that of Bass or the Kiowa. For the moment, though, he's forced to tag along while Bass tracks the Kiowa, intent on retrieving his furs.

Bass intends to sell Lee on when he gets to St. Louis – he speculates that he'll bring a price of fifteen mules and ten bales of cotton, and the precise market value of Lee as a commodity is a subject revisited throughout the film. For the moment, though, Lee and Bass have to forge a relationship by bantering as they make their way through the arid woods and scrubland. (The film was shot in Mexico's Sierra de Órganos National Park.)

Bass: You seem to have an uncommon prejudice against service to the white-skinned race.

Lee: I don't mean to be narrow in my attitude...Mister Bass, couldn't you consider me a captured Comanche? I came on my own two feet as far as the Comanches...And since those Indians captured me from other Indians, I have now got full Indian citizenship.

Bass: Joseph Lee, you ever study the law?

Lee: No sir.

Bass: Well neither did I. But you ain't got a chance in hell of calling yourself an Indian. You're an African – slave by employment, black by colour.

Bass: Now you see the superiority of the white-skinned race when it comes to walkin'.

Lee. Yes sir.

Bass: My ancestors were famous, as liars, walkers, and patriotic in their sensibilities...Of course if someone was to come along now they might figure you owned me. 'Cuz you're ridin' and I'm walkin'.

Lee: But that's not the case sir.

Bass: In a manner of speaking you are the converted image of my pack horse and fur pelts. I'd take good care of them, wouldn't I?

Lee: Yes sir. Because they're valuable wholesale and retail commodities.

By the end of the '60s Hollywood was no longer sure what a western looked or sounded like. A more violent, visually striking version of the western was being made on the other side of the Atlantic, and it seemed like audiences in the U.S. were responding to hybrids of the genre – western comedies (sometimes even with musical numbers) like North to Alaska (1960), McClintock! (1963) and Cat Ballou (1965), putting The Scalphunters in the middle of a brief generic detour that would continue with films as disparate as Paint Your Wagon (1969), Support Your Local Sheriff (1969), Little Big Man (1970), Two Mules for Sister Sara (1970) and The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (1972).

How precisely comic The Scalphunters really is gets tested with the next scene, when Bass and Lee come upon the Kiowa, drunk after discovering a bottle of rum amongst his furs. Bass is about to retrieve his property when a group of scalp hunters thunder into the valley and massacre Two Crows' men, taking scalps from every dead body – a bounty paid by the territorial government that pays out at twenty-five dollars a scalp.

Bass might not have an issue with slavery, but he considers scalp hunting "the wickedest, crookedest trade to ever turn a dollar." He begins tracking them, dragging along Lee, who's constantly looking for an opportunity to escape.

The scalp hunters are an outlaw gang led by Jim Howie (Savalas), at the head of a wagon train that includes several Mexican women and Kate (Winters), his constantly complaining girlfriend. (Dabney Coleman, in his third ever screen role, is apparently part of the gang, but I failed to pick him out.) The outlaws consider Lee a commodity, like the scalps and Bass's furs, and speculate that he could go for up to $1500 on the block in Galveston.

Howie has outfitted his wagon with a brass bed and bookshelves to give Kate a few of the comforts she longs for, and it's Winter's job to provide much of the broad comedy in the story. In one scene Howie cusses Kate out for walking through camp in red tights and a black corset and peignoir, but she replies that "If I had half the boots been stuck under my bed, I bet I could outfit the United States Cavalry!"

Burt Lancaster had been in charge of his career for years, by creating production entities in partnership with agent Harold Hecht and writer James Hill, but by the time he made The Scalphunters he was partners with writer and producer Roland Kibbee, who had worked with Lancaster on pictures like The Crimson Pirate (1952) and Vera Cruz (1954).

Lancaster's record as a producer had been superb up till this point, with pictures like Marty (1955), Sweet Smell of Success (1957), Separate Tables (1958), Elmer Gantry (1960) and Birdman of Alcatraz (1962). The actor was famously loyal, with working relationships that lasted decades and a large entourage. He had enjoyed creative partnerships with directors like Richard Brooks, and by the '60s had become a patron of sorts for young directors like John Frankenheimer and Sydney Pollack.

Pollack had begun his career as an actor and had come to Los Angeles at the invitation of his friend Frankenheimer, who hired him to work as a dialogue coach on The Young Savages (1961), on which Lancaster was both star and producer. After working on TV for a few years he made his first two pictures, The Slender Thread (1965) and This Property is Condemned (1966) before starting work on The Scalphunters.

You could say that Pollack was just discovering his style with the film, which includes very voguish bits of visual business, like transitions that begin with a sudden zoom into out-of-focus backgrounds, and delirious, vaguely trippy scenes like the Kiowa massacre and a drunken party around the outlaw campfire.

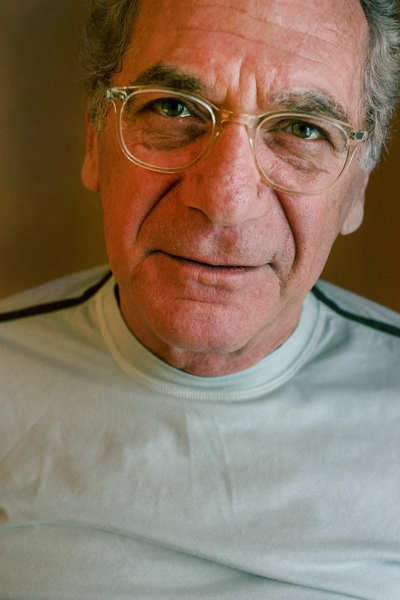

Sydney Pollack, Toronto, Sept. 2006. Photo by Rick McGinnis |

But Pollack was never a director with a distinct visual style. His subsequent career, which ended with his death in 2008, included films as different as the gritty western Jeremiah Johnson (1972), his hit romantic drama The Way We Were (1973), the paranoid political thriller Three Days of the Condor (1975), the smash comedy Tootsie (1982) and epic historical pictures like Out of Africa (1985) and Havana (1990).

Pollack's talent was for responding to the current mood, both in Hollywood and audiences, and producing movies that catered to them, reliably netting Oscar nominations for himself and his actors. His reputation was for making quality pictures, and when he returned to acting in the '90s he appeared in pictures like Robert Altman's The Player (1992), Woody Allen's Husbands and Wives (1992) and Stanley Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut (1999). For as long as I've known his name, Pollack looked like a real Hollywood insider.

When Lee discovers that Howie and his gang are headed to Mexico to hide out from the law for a while, he begins ingratiating himself with Kate, flattering her that she'll need a good domestic servant if she wants to set herself up in style south of the border, and giving her a fine hairdo using agave as a shampoo. He also finds her astrology books and, a quick study, sets himself up as a keen amateur astrologer and palmist, reading the omens in the stars and her hand to tell her that Bass' stolen furs and the bag of scalps have put a curse on the gang that will end in Howie's death.

As Davis told Roger Ebert in 1968:

"In this situation, the escaped slave has to hustle like everybody else. He's no hero with a Nobel Prize; he's a man fighting for his life. And this movie is not about the Unfinished Social Revolution, and how we are all guilty, and all that. It asks a simple question: What's in it for me?

"That's why it's good that the Negro character in The Scalphunters is presented as he would have been in real life. He's got to tread softly, or he'll be back in slavery in a wink. He's got to smile, and make plans."

In the meantime Bass is making sure that Lee's prediction comes true, stalking the outlaw wagon train and picking off the gang with sniper attacks and avalanches. He almost manages it, but Howie pulls off one last double cross, strapping a dead outlaw in his spot on a wagon and hiding in the man's freshly dug grave to ambush Bass and Lee, who he'd sent up into the hills to parley with the trapper.

During their parley Bass expresses his contempt for Lee after watching him get beaten by one of the gang members who objected to the slave dancing with one of the women during the campfire revelry. He questions his manhood for throwing himself in with Kate and Howie and refuses to share a bottle of whiskey with him. "Whiskey's a man's drink and you ain't no part of a man," he tells Lee, who replies:

"You think mighty well of yourself, don't you Joe Bass? You know how long you'd last as a coloured man? About one minute. The trouble with all your fighting, Joe Bass, is you don't now when you've won. Go ahead, kill us all."

"The character I play is a very important one in the movement to get realistic, three-dimensional Negroes onto the screen," Davis told Ebert. "In fact, it's so important that while we were making the movie I didn't want to tell anyone how important it was; I was afraid they'd decide it was a bad idea. Too risky, you know."

At this stage in the civil rights struggle onscreen, moviemakers were careful to delineate good white men from bad white men. Howie and his outlaws are the bad kind – openly racist, like Bruce Dern's Long Hair in The Cowboys (1972), as opposed to the young cowboys and John Wayne's Wil, who are able – like Bass with Lee at the end of The Scalphunters – to overcome their residual prejudice against Roscoe Lee Brown's Nightlinger.

Howie even calls out Bass over and over as a "half breed", and the trapper is notably fluent in Kiowa when talking to Two Crows. And at the end of the film, when Two Crows returns with Kiowa reinforcements and massacres the remaining outlaws, Kate and the women are the only ones left standing, before Winters looks them over and says to the other women "What the hell – they're only men."

The Kiowas' revenge happens while Bass and Lee are oblivious, beating each other senseless in a long, slapstick brawl that ends in a wallow that covers both of them in mud – conspicuously rendered the same colour in front of the Kiowas, who ride off with the trapper's furs. The two men drag themselves off the ground and head off together after them on the back of Agnes, Bass' comically sentient horse.

In Burt Lancaster: An American Life, her biography of the actor, Kate Buford writes that The Scalphunters was "well-received" upon its release in the spring of 1968, despite being undercut by "real-life events – Vietnam, assassinations." She notes that Pauline Kael even liked it, calling it "one of the few entertaining American movies (of) this past year," though making the distinction that, despite being "skillful," it was hardly art – "an equation that was fairly typical of the difficulty critics had with appraising Lancaster."

David Denby, for his part, said that Lancaster was acting with his hair which, in The Scalphunters, "grows as straight up and free as alfalfa."

The Swimmer, the picture Lancaster had filmed just before The Scalphunters but released afterward – and very much more art than his western – didn't do as well, with Newsweek writing that it looked like "a shampoo commercial." Lancaster's next picture with Pollack, the war movie Castle Keep (1969), fared even worse, as did The Gypsy Moths (1969), made with Frankenheimer. Lancaster wouldn't have another hit again until the disaster drama Airport (1970), which ushered in a string of disaster pictures in the next decade.

There is a lot wrong with The Scalphunters; it's too long, for one, and could easily lose fifteen or twenty minutes of Bass' long pursuit of Howie and the outlaws. To modern eyes its treatment of race looks awkward and forced; reviews on Rotten Tomatoes dismiss the script for "trying to find some politically correct civil right's (sic) message" and damn the film altogether as "a seriously misguided and hopelessly dated endeavor that's best left forgotten." Another website lumps it in with "The Worst Classic Westerns Available to Stream Right Now", alongside McClintock!, The White Buffalo, Return of the Seven, The Apple Dumpling Gang and One-Eyed Jacks.

This is certainly not how Lancaster, Pollack and perhaps even Davis hoped the film would be seen, even if they knew what a careful balancing act it was to make messages about race central in a film released the same month as the assassination of Martin Luther King and the signing of the Civil Rights Act. The people who made The Scalphunters – few of whom are alive today – would have been shocked to learn that race remains a live and dangerous third rail, in movies and elsewhere, and that even their distant best-intentions would do little to stop someone, somewhere from regarding an old film as little better than Birth of a Nation.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.