In a development probably not indicative of a healthy democracy, we spend a lot of time talking about our "elites" these days, without anything like approval. I can't help but remember that we're not talking about the same people who occupied that position a generation or two ago. For evidence, there's Metropolitan, a low-budget independent American film from the turn of the '90s, made by a first-time director, but about the sort of people we all assumed sat somewhere near the top of our social hierarchies.

If you believed the eight young people at the heart of the 1990 film, their position at the top was, if not in the past already, irrevocably heading for history's dumpster. The film begins with a caption telling us that it's set in "Manhattan, Christmas vacation, not so long ago." But from the position of 2023 it seems like very long ago, as the next shot is of one of Manhattan's lovely old skyscrapers with its windows lit up to form a cross.

A similar photo was in circulation this Easter; taken in 1956, it depicted a trio of towers in the Financial District lit up like Calvary on Good Friday that year. Writing about the photo, critic Roger Kimball wondered that "1956 was not that long ago. But how much has changed in those 60-odd years! Can you imagine such a public display of Christian affirmation in New York today? Nor can I." Considering that director Whit Stillman shot his movie in 1989, these kinds of religious displays were apparently still commonplace when Tone Loc's "Wild Thing" was in the charts.

After a brief scene where Audrey (Carolyn Farina) despairs over the fit of a gown, the movie properly begins with a wide shot of one of New York's grand old hotels at night – the Plaza, the Pierre or the St. Regis – where a crowd in evening dress, debutantes and their dates, is hitting the sidewalk and looking for taxicabs. Tom (Edward Clements) is loitering by a cab when Nick (Chris Eigeman) apologizes for nearly taking his ride; Tom protests that it isn't his taxi, but Nick insists they head off together with Audrey and another girl to a party at "Sally's," assuming that's where Tom was headed anyway.

"We should share it," Nick says. "That way there's no ill feeling."

This brief exchange, just after we're witness to Audrey's agonies about her looks and wardrobe, should probably be our hint that Stillman's film is very much a comedy of manners, in the style of Jane Austen, a writer of great contention between Audrey and Tom once they're introduced, that night, upon his introduction to the "Sally Fowler Rat Pack" (SFRP) – an unevenly numbered collection of debutantes and their dates, into which Tom is drafted at Nick's urging to even things out.

Here's the thing: almost nobody was talking about Austen at the end of the '80s. It would be several years before Jane Austen's novels became movie staples, starting with the one-two punch of Clueless and Sense & Sensibility in 1995. Stillman's inspiration was that a story about young people navigating what were and weren't suitable relationships for members of their class, even if it was set in the "present day," would by necessity be Austenesque, before anyone was using that term in general conversation.

Sally Fowler (Dylan Hundley) – or rather her parents' vast apartment in a doorman building on the Upper East Side – is host to what turns out to be a crucial but brief social centre of Manhattan's debutante season. Tom is adamant that he's opposed to the season and everything about the class that supports it, but he's drawn into the SFRP despite his protests, first by Nick's insistence that his aversion is insincere, second by Audrey's secret crush on him, and third by the fact that he neglects to return his rented tuxedo on time, and allows himself (with fairly unconvincing protests; Nick's insight was on target) to be swept up in a week or two worth of formal parties and coming out balls, serenaded more often than not by the orchestras of Lester Lanin or Peter Duchin.

Tom likes to pretend he's an outsider to the social rituals of the WASP establishment; the truth is that he's an outcast, having slipped out of it after his parents divorced and he moved with his mother to a cheaper apartment on the Upper West Side, while his father and his new wife retained an Upper East Side address. To justify his loss of status he's become an avowed socialist and a devotee of Charles Fourier, an obscure French philosopher whose American followers founded the (failed) communal community of Utopia, Ohio in 1844.

Yes, he's insufferable, but the members of the SFRP are polite, as these sorts of leftist conversions are apparently common among members of their class, and don't preclude Tom from enjoying the free food, entertainment and company afforded to young men enlisted as escorts during deb season.

Metropolitan is a comedy about character, so it helps that Stillman draws several fine ones. Edward Clement's Tom is a bit of a cypher, so it was probably within the actor's talent to play him as one. (Clement's brief acting career ended a year after Metropolitan, with a role as "Young Crewman" in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country.) More indelible is Chris Eigeman's Nick, the self-appointed defender of the social class that made deb season possible, and an unapologetic snob.

Eigeman would have key roles in Stillman's "WASP Trilogy", which includes Metropolitan and its "sequels – Barcelona (1994) and Last Days of Disco (1998) – though he's often mistakenly described as Stillman's alter ego. More accurately he's the dark side of characters like Tom, Fred (Barcelona) and Josh (Last Days of Disco) – someone whose crucial moral failings are key to the story, and to whatever transformation overtakes the "hero".

Nick is Tom's guide to the world of the deb ball, and seems to have been rehearsing his role as an escort since childhood. He's capable of real insight when he isn't being provocative for sport or simply lying; he convinces Tom to overcome his overstated hatred of deb balls by describing how much more important they are to the girls in the group than to the boys.

"They're on display," he tells Tom. "They've got to call guys up to invite them as escorts. And preppy girls mature socially much later than others do; for many of them this is the first serious social life they've had. If you just disappear now, they're going to take that as a personal rejection."

Nick enlists Tom as his second-in-command and, ultimately, inheritor of his mantle as standard-setter in the SFRP – a role that Nick fails at, not long before Tom discovers that it was neither needed nor wanted.

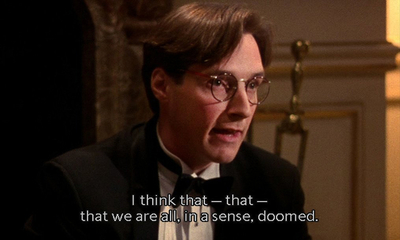

If Nick is Tom's ally, Charlie (Taylor Nichols) is his enemy – in the least threatening possible way. Charlie is an old school friend of Nick's, the most socially awkward member of the SFRP, and obsessed with the decline and fall of their whole class. He calls Tom a hypocrite for being a Fourierist in a rented tux; he's also coined a term – Urban Haute Bourgeois – that he's sure describes their class much better than "preppy" or WASP.

Charlie is certain that, whatever they're called, they're doomed, the first American social class to experience "downward social mobility" as a group. Nick goes further, telling Tom that he thinks their parents are to blame for never preparing them for the real world or instilling the values that had helped them succeed.

"Our parents' generation was never interested in keeping up standards," Nick complains. "They wanted to be 'happy', but of course the last way to be 'happy' is to make it your objective in life."

Tom imagines it possible that their generation might be better than their parents, despite their handicaps, but Nick will hear none of it, and dismisses their generation – and those that will come after, by implication:

"It's far worse. Our generation is probably the worst since...the Protestant Reformation. It's barbaric, but a barbarism even worse than the old-fashioned kind. Now barbarism is cloaked with all sorts of self-righteousness and moral superiority..."

In the light of everything that's happened in the last thirty years, Nick was clearly some kind of prophet.

Charlie has another reason to hate Tom, and it's Audrey, who prefers Tom to him for reasons he can't understand. Audrey is the only girl in the SFRP who matches Nick's description of socially vulnerable preppy girls – an innocent compared to her peers, who has found a real kinship with Jane Austen's heroines and their obsessions with virtue.

Tom is still in thrall to Serena Slocum – an ex-girlfriend, the most glamorous girl in their set, and the object of his infatuation. He had poured his heart out to her in a series of letters that the unsentimental Serena had given away to a classmate – Audrey, who found an earnest charm in them that Serena didn't. Tom incessantly moons over Serena, oblivious while everyone else in the SFRP knows about Audrey's feelings, at least until he ditches Audrey at the St. Regis to take Serena home – a cruel social faux pas from which he almost doesn't recover.

Tom dismisses Audrey's love of Austen and Mansfield Park in particular – a "minor" novel that he uses to dismiss all the writer's work by implication, using arguments he's cribbed from literary critic Lionel Trilling. He has a particular problem imagining the social context in which there would be something immoral about young people putting on a play. Audrey is shocked by his lack of imagination, until Tom admits he's never read the book.

"I don't read novels," he tells her. "I prefer good literary criticism – that way you get both the novelists' ideas and the critics' thinking. With fiction I can never forget that none of it really happened – that it's all just made up by the author."

Tom's easy to dismiss until you remember that, at some point in the thickets of our life on either side of twenty, we were just as likely to make a statement as ridiculous. The characters in Whit Stillman's films all tend to be this hyperarticulate – the unreliable narrators of their own lives, impressed with how a well-turned phrase or rationalization can make almost any inconsistency or risible opinion seem plausible – as long as the person you express it to has as little life experience as you.

Farina's Audrey is an Austen heroine in an ensemble performance – probably the most frustrating part of Metropolitan, but like any Austen heroine we have to assume that her judgment, as good or better than that of anyone else in the story, is what will make Tom redeemable before it ends.

But before we get there we get an Austen villain – the story's Willoughby, Wickham and William Elliot, invested in the person of Rick von Sloneker (Will Kempe), a womanizer with an actual aristocratic title and Serena's current boyfriend. He's Nick's mortal enemy, and his attempt to bring Rick down involves a story about the drunken violation and suicide of one Polly Perkins, which turns out to have been a fabrication, and though Nick insists that Polly was based on real people – "a composite, like New York magazine does" – von Sloneker decks Nick in Sally's apartment on the night of the International Ball, the climax of the deb season.

This gets Nick banished, and he heads off to his father's place upstate from Grand Central that night, gifting Tom his top hat to pass on the torch. In his absence, however, the SFRP falls apart, the escort services of the boys no longer needed. The decline that Charlie had anticipated seems to have started in earnest.

Whit Stillman's background gives him the authority to write about the UHB: the son of an assistant secretary of commerce in JFK's cabinet, he attended the usual succession of prep schools (Collegiate, Potomac, Millbrook) before studying history at Harvard. He briefly worked at Doubleday before being a junior editor at The American Spectator – a resumé item that labeled him and his films as conservative early on, though he has insisted for years that he's apolitical and has carefully avoided political debates.

The class that produced Stillman didn't really get a proper name until the publication of The Official Preppy Handbook in 1980 – edited by Lisa Birnbach as a satire but adopted as an anthropological textbook, etiquette guide, popular history, and shopping catalog when it became a massive bestseller. Stillman wrote his movie into the space Birnbach's book had created, during one of the rare periods where Americans had given themselves the language to talk about class.

The preppy moment had already passed, but the Handbook gave aspirants and strivers a guide to camouflage themselves in the manners, clothes and credentials of the establishment they were replacing in a society that proclaimed that it had become more meritocratic. With this in mind, Charlie's insistence on defining his class before it disappears is understandable.

In the book Doomed Bourgeois in Love, a collection of essays about Stillman's first three films published in 2002, James Bowman writes that "the people Stillman is really writing for are those just below him on the social scale. Not the urban haute bourgeoisie but the suburban petite bourgeoisie who ape their betters even when it amuses their betters to sneer at people like themselves."

In his introduction to the book, editor Mark Henrie explains that the UHB were, in earlier times, called "gentlefolk", which may have been an American euphemism for landed gentry adopted by people technically lacking an aristocracy. "Democratic and meritocratic America has never had much time for gentility," he writes, "and radical ideologies in principle despise the well-born. For these reasons, the gentlefolk tend to appear in our popular art as villains or as fools."

"But Stillman's films insist that there were (and are) true virtues to be found in this class and its ideals. The manners of Metropolitan, the courage of Barcelona, the opening to grace in Last Days – each captures a facet of a kind of knight-errantry which is a permanent human possibility."

The girls in the SFRP – with the exception of Audrey – seem to be far less vulnerable than Nick imagined them to be, and once launched they start dating outside their social circle. Called "tiresome" for insisting on hanging around Sally's parents' apartment, the boys realize that their usefulness is over, with the usually bibulous, often comatose but now sober Fred (Bryan Leder) telling Tom and Charlie that they were just "way stations between dates."

I don't come from Stillman's class – not even close – but I did attend a (then somewhat second-rate) Catholic private boys' school around the time Metropolitan is set, and my circle of male friends found ourselves in a similar clique, the companions and erstwhile dates to a group of girls from one of our sister schools, all of whom were more definably middle class, loosely grouped around another Sally. Like Tom, Charlie and Fred we were surplus after graduation, their train having pulled out of our way station. Whether this was a lesson in coded class prerogatives or female hypergamy – or both – was a question I pondered for years.

Cut adrift in Manhattan, Tom and Charlie end up in a bar (I imagine P.J. Clarke's, though there used to be dozens of bars like it in midtown and above) where they meet a character called "Man in Bar" in some places but also given the name Dick Edwards (Roger W. Kirby) – a middle aged UHB who asks them if the balls and parties of the Christmas deb season are still a thing.

"I wouldn't put much stock in them," he advises.

Charlie and Tom explain the concept of UHB and their worries about the doom of their social class but Dick tells that many of his colleagues were actually successful, though he can't say for certain if they enjoy their lives. "The acid test is whether you take any pleasure in responding to the question 'What do you do?' I can't bear it."

He tells them that "not everyone from our social class is doomed to failure...We simply fail without being doomed."

But Tom and Charlie get a taste of failure when they try to sally forth to the Hamptons to save Audrey from the clutches of Rick von Sloneker, worried that she has "given up on Jane Austen." They get cash from a bank after Charlie's parents' credit card is declined at the car rental office, and then discover that neither of them can drive. Their very Austenesque quest to preserve feminine virtue is done in a Checker cab, and they find out that Audrey was never in peril to begin with, leaving the trio by the side of a winter road in a summer town, trying to thumb a ride back to town.

Despite being dubbed a conservative, even reactionary film, Metropolitan was a hit when it was released, making $7 million on its $225,000 budget. I was even flown to New York by the very left-wing free weekly I was working for to photograph Stillman for our cover. It's hard to believe now, but films like Metropolitan weren't just being made, but could find a place in the cultural dialogue thirty years ago.

Nichols and Eigeman would return for Barcelona, and Farina, Nichols, Leder, Hundley and Kempe would do cameos as their Metropolitan characters in The Last Days of Disco. After he completed his trilogy, though, Stillman entered a wasteland, writing unfilmed scripts and getting considered for pictures that were never made. He apparently made ends meet as a yacht salesman.

Stillman finally returned after a 13-year hiatus with Damsels in Distress (2011), a comedy set on a college campus, starring Greta Gerwig. He finally got to make his Jane Austen film with Love & Friendship (2016), based on Lady Susan, an early, obscure short novel by the author, which brought back Kate Beckinsale and Chloe Sevigny from The Last Days of Disco, as a scheming widowed aristocrat and her American friend.

The International Ball (described by Nick as "inorganic" to northeastern WASP society) persists, though many of the other balls are either much reduced or gone altogether. You can still book the Lester Lanin Orchestra to play your society events, even though Lanin himself died in 2004, but his rival Peter Duchin is still alive and apparently available for bookings.

In spite of Nick's concern they still haven't knocked down the St. Regis – now part of the Marriott chain and renting its cheapest rooms at well over a thousand dollars a night off season. But the world looks very different from the one whose decline concerned Tom and Charlie when Metropolitan was released, with much of the blame for the worst of it aimed at whatever social elite took the place of the UHB.

As Roger Kimball wrote in his essay on those Easter crosses, "We have embraced our hatred and antipathies with uncommon zeal, to the point where the words 'secession' and 'national divorce' are once again circulating in earnest. A snarling partisan spirit is alive and rancorous."

"We have in all essentials transformed ourselves from a republic into an oligarchy, trampling on such quaint guardrails as the separation and disbursement of powers. We have loaded ourselves—or, rather, we have been loaded—with eye-watering, incomprehensible mountains of debt. And we have loudly rejected the claims of traditional morality and religion as so many otiose and unprogressive holdovers from a discredited past."

Metropolitan's great achievement might actually have been introducing the concept of "downward social mobility" – it even appeared at the top of its movie poster – to people of all classes who'd learn what it meant. As Charlie tells Nick, "We hear a lot about the great social mobility in America with the focus usually on the comparative ease of moving upwards. What's less discussed is how easy it is to go down. I think that's the direction that we're all heading in."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.