My father died when I was four years old, so my memories of him are scant and fleeting. But the most vivid is waiting for him to get back from the office (he had worked his way from blue- to white-collar positions at Supertest, a major oil company in Canada, now owned by BP) so we could watch Looney Tunes cartoons on the big couch in our living room, on the black and white console TV that sat in the corner, by the picture window, next to where we put up the Christmas tree.

There are a lot of films I love (see below), but I'd rather watch a great Warner Brothers cartoon (or even a middling one) than almost anything else. I'm just that kind of idiot.

But my favorite Looney Tunes of all is What's Opera, Doc?, a 1957 cartoon directed by Chuck Jones and included on every list of the best cartoon shorts ever. It was made near the end of the heyday of the Warner Bros. cartoon – studio executive David H. DePatie would close down the animation unit in 1963, a year after Jones was fired from the studio for moonlighting on a script for rival UPA.

Like most kids in my generation, my first and most vivid exposure to classical music was in Looney Tunes cartoons (and Disney's Fantasia). Warner's animation department had been formed to showcase songs in its musical library through their Merrie Melodies and Looney Tunes series, but their growing success over the years with characters like Porky Pig, Daffy Duck and, ultimately, Bugs Bunny had made the perennially underfunded cartoon studio a creative powerhouse, staffed by talents like animators Tex Avery, Jones, Friz Freling, Robert Clampett, Arthur Davis, Robert McKimson and Frank Tashlin, as well as composer Carl Stalling, designer Maurice Noble, writer Michael Maltese and voice actor Mel Blanc.

What's Opera, Doc? was effectively a re-write of Tex Avery's A Wild Hare (1940) the first pairing of Bugs with Elmer Fudd. Just one in a long line of Warners "screwball hunting pictures" (in a phrase coined by animation historians Jerry Beck and Will Friedwald), it transcended merely being a gag delivery system with music and art direction and by pushing the usual subversion of cartoon conventions – a Looney Tunes specialty – just a little bit further.

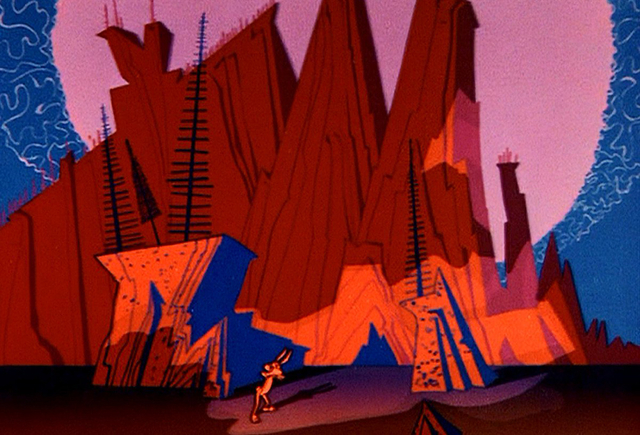

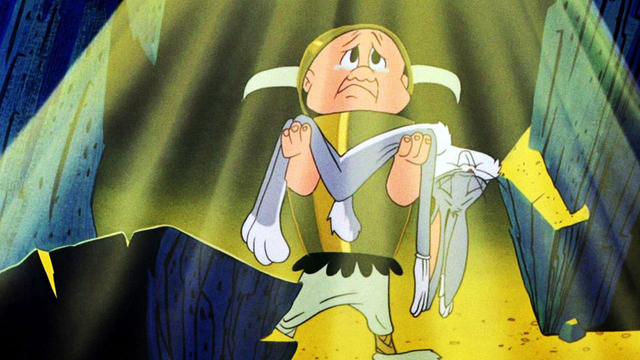

The cartoon begins with the music from the storm scene in Wagner's The Flying Dutchman, over a wildly stylized theatrical landscape against which the shadow of a Norse warrior in his horned helmet throws powerful shapes – a sequence that parodies the "Night on Bald Mountain" segment in Fantasia. As the music diminishes, we follow the shadows to their origin – Elmer Fudd dressed as Siegfried, the ancient German demigod, and hero of Wagner's Die Walkure and Götterdämmerung.

There was a time when an audience would have understood all of this, if only in a vague way. In the middle of the 20th century musical appreciation was still considered a major part of school curricula, and middlebrow culture – attacked by Sinclair Lewis and H.L. Mencken in the '20s and vilified by cultural critics like Dwight Macdonald – still thrived. Conductors like Arturo Toscanini, Leopold Stokowski and Leonard Bernstein and musicians such as Glenn Gould, Pablo Casals, Van Cliburn and Beverly Sills were celebrities, and the average middle-class American had at least a few classical records in their hi-fi.

Opera companies and symphonies thrived and nearly everyone could recognize popular melodies from a symphony or opera, even if they only knew them from Mario Lanza or Liberace. Warners cartoons were part of this cultural menu, and Jones in particular loved to use classical music in his films, from Baton Bunny (1959) to Rabbit of Seville (1950) to Long-Haired Hare (1949), with its satire of Bugs-as-Stokowski taking revenge on a high-handed tenor.

So the first laugh in What's Opera, Doc? is the sight of Elmer Fudd in Siegfried's horned helmet. The screwball hunting comedies had begun with Porky Pig and his quarry Daffy Duck, but Fudd had taken over the role, hunting Daffy, then Bugs, then both of them at the same time – an inept figure kitted out in absurd costumes, the weekend sport hunter easily defeated by the wily Bugs or the chaotic Daffy. By the time What's Opera, Doc? came out it was a comic convention as venerable as the Marx Brothers baiting highbrows and authority figures, or Abbott and Costello being pursued by ghosts and monsters.

For What's Opera, Doc?, Fudd has extra steel in his spine. After singing his signature line "Be vewwy quiet, I'm hunting wabbits" he sets off across the cartoon's more-than-usually stylized landscape after rabbit tracks that lead to a hole in the ground, into which he vigorously thrusts his spear, singing "KIWW THE WABBIT!" over and over to the melody of "Ride of the Valkyries."

After World War Two, Wagner, along with his family and the Bayreuth Festival he'd founded to enshrine his musical legacy, had a bit of a Nazi problem. He had been Hitler's favorite composer, and the dictator had become close friends with Winifred Wagner – wife of the composer's son Siegfried – and principal patron of the festival, which was actually run by the Nazi party during the war.

(It was a special reward for soldiers to be sent to enjoy Bayreuth's productions while recuperating from wounds – one that many of them found as trying as a Russian artillery barrage, but who could complain as a "guest of the Führer"? There is no shortage of ways you can suffer in a totalitarian regime.)

Bayreuth didn't open again until 1951, after Winifred had been sidelined in favour of her sons Wolfgang and Wieland. For decades the festival had recycled threadbare sets from Wagner's day, but with the official clean break from the past after the war, Wieland Wagner reimagined the productions with expressionistic and minimalist sets and staging to create a more abstract Wagnerian universe, carefully distanced from the Norse Aryan cliches so beloved of the Nazis, and this is the "New Bayreuth" that designer Maurice Noble parodies so wonderfully in What's Opera, Doc? – crazy sets full of stark, thrusting mountains, improbable ruined castles and battlements, and exaggerated classical columns and follies swagged with garlands.

While Elmer stabs at the rabbit hole, Bugs emerges on cue from an adjacent one, casually walking over to inquire what he's up to with his signature phrase, echoed in the cartoon's title. As ever, Elmer doesn't recognize Bugs as a bunny; his chronic visual agnosia is one of the longest running gags in Warners cartoons. He tells Bugs that he's hunting rabbits with his "speaw and magic hewmet."

"Spear and magic helmet?" Bug asks.

"My speaw and magic hewmet!" Elmer proclaims.

"Magic helmet?" Bugs scoffs, clearly skeptical.

Elmer proceeds to demonstrate said magic helmet to Bugs, summoning the elements and storm clouds to blast the tree under which Bugs is standing with a single bolt of lightning. "Bye-eee," he says, scampering away, at which point Fudd realizes he's been talking to the rabbit the whole time. As gags go, it somehow never gets old.

Elmer-as-Siegfried runs off in pursuit of Bugs, which sets off another evergreen gag. "Cross-dressing Bugs" is one of the oldest Bugs stratagems, going back past A Wild Hare to 1939, and Hare-um Scare-um, a cartoon directed by Ben Hardaway and Cal Dalton, back when the studio was desperately trying to give shape to their cartoon rabbit, after he was created a year earlier in Hardaway's Porky's Hare Hunt.

Hardaway's nickname was "Bugs," and for the brief period when his creation was loosely considered his property he was known around Termite Terrace as "Bugs' bunny", and the name would stick long after Hardaway left the studio. In Hare-um Scare-um proto-Bugs is being chased by a hunter and his dog, and the bunny dresses as a female dog to briefly seduce the dog.

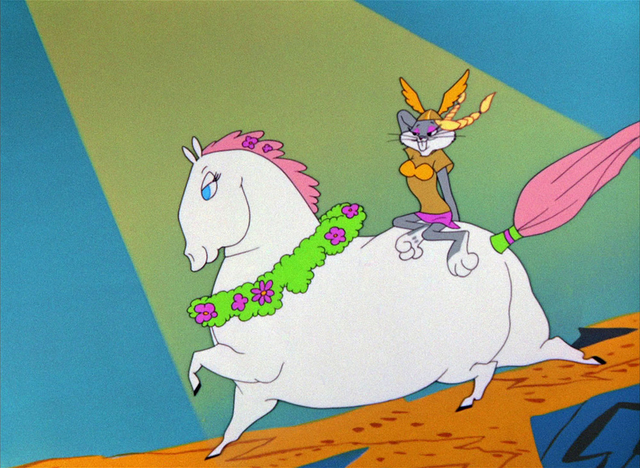

By the time What's Opera, Doc? came out Bugs had done drag in dozens of cartoons, so the audience wouldn't have been surprised to see him dressed as the Valkyrie Brünnhilde, complete with horned helmet and blonde braids, riding to meet Fudd on the back of a comically obese white horse. This was a callback to Herr Meets Hare, a 1945 wartime propaganda cartoon directed by Friz Freling and written by Michael Maltese, where Bugs dons a similar get-up, right down to the corpulent white horse, to trick Hermann Göring, galloping onscreen to the "Pilgrims' Chorus" from Tannhäuser, inspiring Göring to change from his black uniform to Siegfried's horned helmet and animal skins.

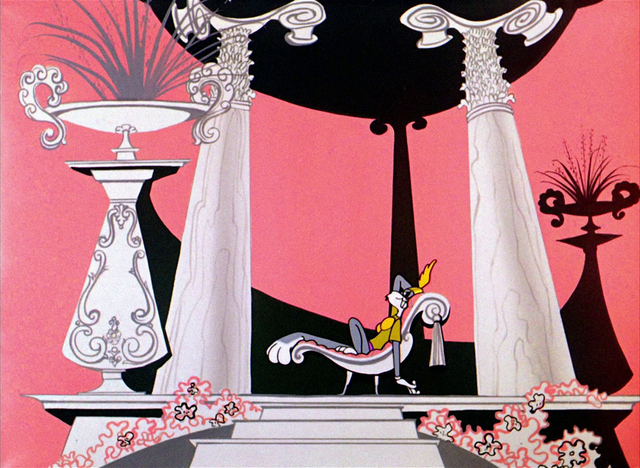

Maltese recycled the gag for Jones' film, even writing a love duet ("Return My Love") to the "Pilgrims' Chorus." After dancing a ballet to the bacchanal from Tannhäuser, Elmer and Bugs sing to each other as he climbs the endless steps to the towering neoclassical folly where Bugs-as-Brünnhilde languidly vamps. (Both Mel Blanc and the uncredited voice of Fudd, Arthur Q. Bryan, had fine voices; Bryan was a tenor on the radio in the '20s.) The deception lasts until Bugs' helmet and braids fall off during their embrace, and Fudd flies into a rage, summoning all the power of his "magic hewmet" to "kiww the wabbit" with a massive bolt of thunder.

It wasn't like Fudd beating Bugs was unprecedented – he'd managed the feat in Freling's Hare Brush (1955) and Jones' Rabbit Rampage (1955) – but it must have been a shock to see that Elmer's lightning had actually killed Bugs, who lies in a pool of light under a broken flower that weeps bathetically over the broken bunny.

This fills Elmer with remorse, and he weeps ("Po widdow wabbit. Po widdow bunny.") as he picks up Bugs' body, cradling it as he walks off into the brilliant rays of a Wagnerian twilight. By 1957, of course, the fourth wall of any Looney Tunes cartoon had been utterly demolished, and Bugs lifts his head to look back at us and say "Well, what did you expect in an opera? A happy ending?"

Jones knew he was making something exceptional with What's Opera, Doc?, which cost several times more than the average Warners cartoon, and he pulled it off by secretly cannibalizing time and labour from other films, churning out a Roadrunner cartoon in just three weeks, for instance. Despite this, the cartoon didn't get nominated for an Oscar, and it would be years before there was a consensus that it was Jones' greatest cartoon, and probably the best Looney Tunes ever.

It would be Arthur Q. Bryan's last time voicing Fudd; a strike prevented him from working at Warners the next year, and he died of a sudden heart attack in 1959. The studio was shut down the year before I was born, and my earliest experience with Warners cartoons would be the edited versions featured in the syndicated TV series The Bugs Bunny Show – probably what I was watching with my father on our couch nearly sixty years ago.

As this is my 100th column, it seemed like a good time for readers to get to know a bit about me, so I asked you to Ask Me Anything, and several readers sent along some questions, which I will try to answer as honestly as possible.

Nicola Timmerman asks "Just wondering how you got this gig. Did Kathy recommend you? Did you ever aspire to make films?"

Kathy Shaidle was one of my dearest friends, and when Mark visited her shortly before she passed they discussed someone taking over the column. Apparently Kathy said I was the only choice, which was terribly flattering, and a few months later Mark had Andrew Lawton email me to ask if I'd be interested in taking over for a summer, with Andrew as my editor. The summer was extended and here I am today, once again grateful to Kathy for her friendship and generosity.

I'd be lying if I said that I never thought about making a film. Back in the early days of my career as a photographer I did work as cinematographer/cameraman on a couple of student films, for my then-girlfriend and a mutual friend. Years before that I even took a course in screenwriting (before I owned a camera or entertained any thoughts about professional photography.) And I have quite a few friends who work in the film industry.

And if I needed further evidence of my ambitions, there's this thing:

It's a Bolex 16mm movie camera I bought some time in the 1990s, with money that could have been spent on still cameras or lenses or photo gear or a short vacation or even rent. I obviously harboured some ambitions in the moving picture direction; and then there's this:

This is a Uher reel-to-reel tape recorder my brother-in-law picked up around the same time. (I remember him telling me that it was the same make Nixon used in the White House, which for someone fascinated by the 37th president, made it even more intriguing.) I kept them both, vaguely intending right through the digital revolution and the arrival of smart phones to make some short, experimental films – the kind of things that require neither scripts nor actors. I think the plan was to make little movie versions of Joseph Cornell's boxes at some point. Or not. I actually have no idea what I was thinking.

In the end I didn't do anything with either the Bolex or the Uher. (Though I did cannibalize a couple of the camera's lenses to use on my digital mirrorless camera in the last couple of years.) My ambitions, such as they were, weren't strong or fully formed enough to actually motivate me to do anything concrete. (It didn't help that film and developing are expensive, and that editing was a further skillset that I lacked sufficient ambition to acquire.)

In the end, I'm just a stills and words person. I know just enough about how hard it is to make a watchable film – short or long, experimental or commercial – to discourage someone like me from trying.

Josh Passell writes "I'm interested in your thoughts on the likenesses and differences between film and photography. One of the all-time put-downs of a film (in my opinion) is that it had great cinematography. Of course, many films do, and cinematographers often become alter egos of directors who work with them over and over. But of course a sunset is going to look lovely in 70mm with CGI tweaking, and if that's the first thing you have to say...

"At the same time, as your photographs make abundantly clear, actors and actresses are breathtaking to behold, either through natural beauty, nakedly expressive faces, or both. I had a film professor who used the term 'significant image' to describe a shot--a knife, a dead body, a beautiful face--that left an imprint on the retina or in the memory past long its screen time. (I think of Rita Hayworth's hair-flip in Gilda in the last category: once seen, never forgotten.)"

One of my oldest friends is a cinematographer who works on both sides of the Atlantic, and he once complained to me about people who rave about how beautiful a film looks (and even nominate it for awards, sometimes getting it voted to win) who are mostly talking about lovely establishing shots: sunsets and nature – the work of the second unit, not the principal cinematographer and his crew preoccupied with the business of shooting dialogue and plot.

In essence, he was saying that people (some of whom should know better) respond to the kind of shots that can be captured with a little bit of luck and skill, and ignore the ones that do the real work of actually telling the story. And it's a fair complaint; I'm often amazed at how many likes a quick cellphone snapshot I post on my Instagram account will get, compared to a still life or portrait that I worked hard to light, compose and pose.

Not quite the same, but not too far away, is what photographer Duane Michals once wrote, that "celebrities are the easiest of all to photograph. There is no such thing as a bad celebrity portrait. Even a bad picture is a good one...When someone says, 'What a beautiful photograph' upon viewing a portrait of a handsome man, what they are saying is 'What a handsome man.' Most often it is an ordinary photograph of a beautiful person. If the same photograph were of an ugly person, would it be an ugly photograph?"

Rita Hayworth was famously (and tragically, for her at least) beautiful. That she was also famous only multiplied her beauty, so anything she did that highlighted that beauty and charisma was going to be "significant," much as nearly any one of my own celebrity portraits will probably be more popular (or culturally important, at least as long as the subject's celebrity abides) than any other photo I took that required all of my effort and skill. That's why we remember most movies more for their stars than almost anything else that made them "good" or "interesting."

Still not sure I answered your question, but I hope I got at least halfway there.

Gordon MacMichaels asked "I can readily see your columns being published in an eminently readable collection of essays. What do you see as the organizing principle of your columns? I guess I'm asking for a sneak preview of the Author's Foreword or Introduction."

First of all, thank you, Gordon. I would love to see a collection of my columns in print, though I haven't a clue who would undertake the onerous task, or who would buy enough of it to make it worth their while. But like every writer, I live in hope.

If my columns have an organizing principle, it's that I'm more interested in the context and circumstances of a film and its cultural longevity (if it had any, and if not why not?) than in my own subjective opinion of whether it's any good. (In short, no thumbs up or down from me.)

I am not a film buff. I need to come clean now: I care more about photography, and music and books, and even fine art and architecture, than movies. But for some reason I have found myself writing about films at regular intervals throughout my whole career. (Glibly I can say that I keep trying to get out but they keep pulling me back in.)

I do, however, have a more than decent collection of DVDs and Blu-rays, acquired over my last couple of stints reviewing films. And I have the insatiable curiosity that comes from being largely self-educated, so researching and writing a column involves learning a lot of things I didn't know, with my main task passing that on to the reader. If I happen to venture an opinion somewhere along the way, I hope it will be forgiven.

Gordon also asks "what assumptions you may hold concerning the film interest of your readership", suggesting a scale ranging from happy ignorance of movie history or art to an enthusiast's bountiful knowledge and bottomless opinions.

If I have an ideal reader, it's someone who doesn't need to have everything explained or spelled out to them to get up to speed with a picture. Even better, someone who's willing to go outside their comfort zone and read about a film (or a director or a star or a time period) that they'd normally ignore.

My choices of films to write about here might seem random. I try hard to avoid films that have been written about a lot, and by far more insightful writers than myself. I'm not sure I have anything new to add about John Ford, or Hitchcock, or Orson Welles at this point in time, though if I can find my way toward some luminary director via one of their more obscure pictures (as I attempted when writing about Hitchcock's only screwball comedy) I'm up to the challenge.

I own at least three fat box sets of John Ford pictures; one day I swear I'll take a shot at him.

Steve from Manhattan asks me if I would "care to mention your three favorite films—possibly with a brief note on why you like them?"

Tough question. Like most people cursed with strong opinions, I have a list, though it changes frequently. I have already written about my favorite film here – Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West. Nearly everything I need to say about that film is in my review. So I'll talk about the three runners-up, starting with:

2. Patton (1970). I saw this film for the first time in the library of my Catholic all-boys' high school, during one of those "have the kids come in but let them wear regular clothes and pick some fun activity so the teachers can half-ass it" days. I don't know how I'd missed seeing Patton until I was fifteen – like most boys in my generation war films had replaced westerns as my favorite action movie genre – but I was captivated from the moment George C. Scott walked in front of that huge US flag and gave that blood and guts speech to his offscreen troops.

I am aware that this is neither a "great movie" nor even a remotely accurate war film. (Like most war movie nerds, I cringe when I see Rommel's troops advance in front of M48 Patton tanks at the Battle of El Guettar, to be ambushed by Patton's M41s and M47s, mostly produced in the '50s and '60 and rented from the Spanish army of General Franco. At least Franco was able to lend them some Heinkel He 111s.) And I'm aware that director Franklin J. Schaffner was a journeyman director at best, albeit one in the middle of a quartet of films that would make his reputation (including Planet of the Apes, Papillon and – weakest of the four – Nicholas and Alexandra.)

What the film does have is Francis Ford Coppola's script, which boldly explores the contradictions and flaws in Patton's character and reputation, and (most of all) Scott's performance – one of the most riveting I've ever seen on film, and one that he knew, as soon as he was done, would probably overshadow everything else he'd ever do. (Which is incredible, considering that his subsequent career included The Hospital and Hardcore, as well as playing Benito Mussolini, Ebenezer Scrooge and an Ernest Hemingway alter ego in Islands in the Stream. But he was right.) As far as I'm concerned, the film is an example of how getting just two things right can still make an eminently watchable picture.

3. Lawrence of Arabia (1962). Like Patton, I've lost count of how many times I've seen this movie. I know I've seen it onscreen on the closing nights of at least two movie theatres here in Toronto, before these cinemas were either turned into an "event space," the façade of a (now-closed) Pottery Barn or demolished outright for a condo.

The most epic epic to ever epic, it doesn't get just one or two things right, but excels at nearly everything it needs to do. There's Robert Bolt and Michael Wilson's screenplay, Peter O'Toole's incredible performance (Is Lawrence a hero or a madman? Does it matter to posterity?) and David Lean's direction. Some people think that Bridge on the River Kwai was his best film, and they may be right, but considering how many more times I've watched Lawrence, I have to be honest and give this one my vote for the greatest Lean epic.

4. Goodfellas (1990). I struggle to avoid falling into lockstep with the cult of Scorsese. Taxi Driver is a great film, but I don't care if I never see it again. (If forced at gunpoint, I'd rather sit through New York, New York one more time, one of his biggest flops, which at least has the distinction of being an honest, ambitious failure – the best kind.)

I will stop and watch this film if I come across it on TV, whether at home or in a hotel room or surfing channels at low volume late one night after everyone's asleep while visiting relatives. (I have terrible insomnia, and have for years.) I don't need sound – I can repeat nearly every line of dialogue by heart by now. If I need proof of how a film can succeed on purely cinematic terms, there's no need to go further.

More runners-up: Apocalypse Now (1979), The Maltese Falcon (1941), Das Boot (1981), Dr. Strangelove (1964), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), You Can't Take It With You (1938), His Girl Friday (1940), From Russia With Love (1963), Sexy Beast (2000), Career Girls (1997) The Leopard (1963).

I hope I answered everyone's questions satisfactorily, and if there are any more, feel free to put them in the comments. With luck, we might try this again in a hundred more columns.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.