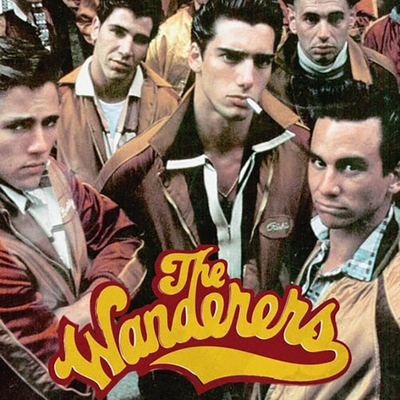

When Philip Kaufman's movie The Wanderers came out in the summer of 1979, it had the misfortune to hit theatres less than six months after The Warriors – another film about teenage gangs in New York City, albeit a far more stylized and fantastical one. Kaufman's film was a period piece, and much more a coming-of-age movie than an action picture, but Walter Hill's The Warriors was a real sensation, its box office boosted considerably by controversy about the film spawning copycat waves of gang violence.

The resemblance of the two titles didn't help, and Kaufman's movie lived for years deep in the shadow of Hill's. There are, sadly, no statistics available for people who rented or streamed The Wanderers, expecting to see a film about a gang fighting other cartoon gangs all the way from the Bronx to Coney Island in some fantasy of Abe Beame's bankrupt New York City, only to sit through a picture about outer borough Italian teenagers in the era of Frankie Valli and Dion.

There are, to be sure, discrete stretches of Kaufman's film where it seems to enter the nighttime nightmare urban dystopia of Hill's picture, but there's no way to tell whether that was intentional or simply an eruption of cinematic zeitgeist. And in any case, Kaufman's film was more part of a demographic cultural moment, whose scope and importance wouldn't really be understood for years.

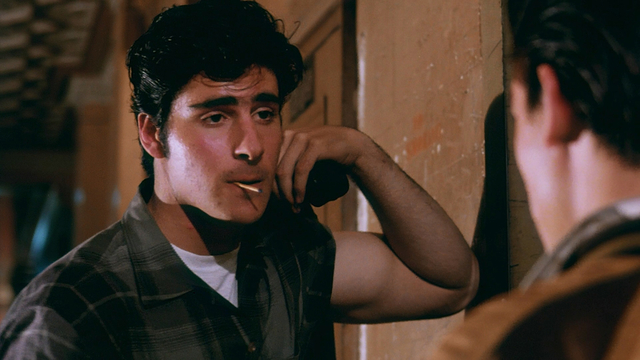

The film begins in a darkened living room, lit only by the Three Stooges on a black and white television, where a young couple wrestle on the couch. Richie (Ken Wahl) is trying to persuade Despie (Toni Kalem) to let him go all the way; despite her reluctance he succeeds, though at the (literally) climatic moment, he hears whistling from the street outside.

Richie is a member of The Wanderers, a gang based in the Fordham Heights area of the Bronx, and fellow Wanderers Joey (John Friedrich) and Turkey (Alan Rosenberg) have provoked the wrath of another gang, the Fordham Baldies, led by the massive Terror (Erland van Lidth) and his diminutive girlfriend Peewee (Linda Manz). While fleeing the Baldies through the alleys and narrow courtyards between tenement apartment buildings their panicked whistle manages to attract Richie and Buddy (Jim Youngs), but only gets the four of them cornered at the cramped junction of four alleyways.

They're about to receive a royal beating when Perry (Tony Ganios) emerges from the shadows. He's a big kid, new to the neighbourhood, and able to fight off enough of the Baldies to save the Wanderers and make fast friends with Joey, who lives on the same floor of the projects, with his abusive, bullying dad (William Andrews), a onetime champion bodybuilder, and submissive mother (Olympia Dukakis).

Perry's first day at his new school with Joey gives Kaufman plenty of opportunities for exposition, introducing the tense ethnic mix of the area, each of which has its corresponding gang, though the big conflict is between Italian-Americans like the Wanderers and African-American gangs like the Del-Bombers. Less than twenty minutes into the film and the script, written by Kaufman and his wife Rose, has packed in more racial epithets and triggering moments than a month of HBO.

Kaufman's film was based on a 1974 novel by Richard Price, who collaborated with the Kaufmans on the movie, even helping Philip Kaufman compile the soundtrack and its cross section of pre-Beatles US Top 40. The Kaufmans' script shuffled around the names and plot to make Price's picaresque story more coherent as a movie, but much of the classroom confrontation between the black and white students is in both versions.

In the movie, the boys' teacher Mr. Sharp is played by the portly, middle-aged Val Avery. In the book Sharp is "a tall, lean, athletic guy...young, in his thirties" who had been "Warlord of the Red Wings, the most feared gang in New York City after the war." His social studies class is "a special class for punks" and Sharp is assigned to teach about racial harmony during "Brotherhood Week," and begins by writing Lincoln's "All men are created equal" on the blackboard.

"Sharp was struck with a giddy thought," Price writes in his novel. "When he was a Red Wing he was known for leading charges against armed gangs with the recklessness of a kamikaze. He was often overcome with a crazy feeling, a disregard for danger that made him one of the scariest guys in a very scary gang. Over the years he'd mellowed, but every once in a while he got a flash of the old insanity..."

In both the book and the movie Sharp decides to wade into the conflict between his students – mostly black and white, with a sprinkling of Jews and Puerto Ricans – by challenging them to list all the racial slurs they use against each other over the course of the average day. He tries to make a point about the power of words while trying to undercut their potential for harm ("sticks and stones") but it ends as badly as you'd expect and before the class can erupt into full warfare Richie and Clinton, the leader of the Del Bombers, agree to take the battle outside, after school.

This presents a problem for Richie; there are more Del-Bombers than Wanderers, and to even the sides they need to make an alliance with other gangs, like the all-Chinese Wongs or the Baldies – the most intimidating of all the Bronx gangs next to the psychotic, feral Irish Ducky Boys. Using Turkey as a middleman – he's halfway between the Wanderers and the multi-ethnic Baldies, and hoping to jump from the former to the latter – they try to parley with Terror, but end up stranded with their pants down on a bridge in a park after the Baldies play a game of "rock and cock" with them.

Richie's problem ends up halfway solved when Despie's father Chubby Galasso, head of the local numbers racket, negotiates with his opposite numbers in the black underworld and turns their rumble into a football game that he can run bets on – hinting heavily that the Wanderers had better win.

Price, who was born in the Bronx and raised in the projects there, based his novel on memories of his youth, and most of the gangs in the film had real-life counterparts, though they might not have been active at the same time. The Wanderers, his first novel and almost inevitably at least semi-autobiographical, took its title from the 1962 hit single by Dion DiMucci, formerly front man for Dion and the Belmonts, a Bronx native and a onetime Fordham Baldie, though the real Baldies weren't the leather-clad skinheads imagined in both the book and the movie.

One of the major changes the Kaufmans made to Price's story was grounding it more specifically in the events of 1963. This began with the casting of Karen Allen as Nina, a small but pivotal character in the last chapters of Price's novel who becomes a major one in the movie – a vaguely beatnik girl carrying a copy of Lady Chatterley's Lover and a guitar case while walking down one of the streets near Grand Concourse and Fordham Road.

Allen is probably the only actor in the film recognizable to most audiences today (though Toni Kalem would later have a recurring role as Angie Bonpensiero in The Sopranos). She meets Richie when the gang are playing "elbow-tit", and while there's an obvious attraction, he passes her on to Joey, the most artistically inclined member of the gang, who falls for her.

The Wanderers is a very Baby Boomer story – one of a number of films told by and to that demographic, about the onset of adulthood in the very culturally specific circumstances that generation had only recently experienced. The blueprint is Peter Bogdanovich's The Last Picture Show (1971), set in Texas in 1951 but very much about young people chafing against their elders and longing for escape while frightened of the imminent changes they're hastening, through rebellions that are, on the surface, sexual as well as cultural.

The real milestone for this informal subgenre was American Graffiti (1973), which hit all the keynotes resoundingly and became a major hit. A year later The Lords of Flatbush, starring pre-stardom Sylvester Stallone and Henry Winkler, told a story remarkably like The Wanderers, but more low key and less stylized. Further films that explored the theme were Diner (1982) and Baby It's You (1983), the latter with a story more explicitly about class.

Young women in this period would have to wait until Shag (1988) to see their story told, though by that point Lawrence Kasdan's The Big Chill (1983) had effectively put a full stop to the genre by shifting the setting to the first Boomers arriving at the uplands of early middle age, reliving the music and rebellion of their youth as nostalgia.

Price published his novel barely a decade after the time it recalls, and more than the movie it's full of nearly delirious recollections of teenage sex, evoking all the obsession and confusion and mortification we do our best to forget with subsequent decades. Kaufman distills most of this into a single party scene at Despie's house, where a game of strip poker leads to Richie and Nina hooking up in her car before a failed attempt by Turkey and the Baldies to crash the party leads to Turkey's death when he accidentally strays into the Ducky Boys' turf.

Richie ends up estranged not just from Despie but the rest of the Wanderers and Joey in particular. Despie – pregnant with Richie's baby – reconciles with him during a pivotal scene (wholly invented by the Kaufmans) where they tearfully watch news reports of JFK's assassination on the TVs in the window of an electronics store - a scene inspired by Kaufman's own memory of the day, while he was shooting his first film in Chicago.

"Suddenly people are coming by crying and teary-eyed," Kaufman recalled in an interview with the BBC in 2020. "We followed them and moved into this store with all these TVs on, and there was the Kennedy assassination. That was something I sort of tried to replicate in the film with Richie – that same mood and feeling – the tragedy. Music, politics, everything was altered in that moment."

The JFK assassination, like so many of the events that happened during the Boomers' youth (Sputnik, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the assassinations of RFK and MLK, riots in Newark, Detroit, Los Angeles and elsewhere) helped foster a generational conviction that they were living in the most important time, that their experiences were unprecedented, and their actions had palpable effects on the world.

This explains two of the other major interpolations into Price's story by the Kaufmans. Near the film's climax, during his stag party (unaccountably somewhere in Greenwich Village, far from the Bronx), Richie sees Nina and follows her to Gerde's Folk City, where Bob Dylan is singing "The Times They Are a-Changing." Richie watches through the window, unable to enter, his own life now set on marriage and fatherhood and a position in the Bronx numbers racket run by his father-in-law.

On the same night we see Perry and Joey escape from their families and the Bronx, setting out in Perry's car for California – San Francisco in particular. (Kaufman moved there in 1960 and still calls it home.) In Price's novel the two young men opt to head to Boston where they can get their merchant marine papers and ship out – a very different, less culturally loaded destination.

(In retrospect, both moments seem a little too on the nose.)

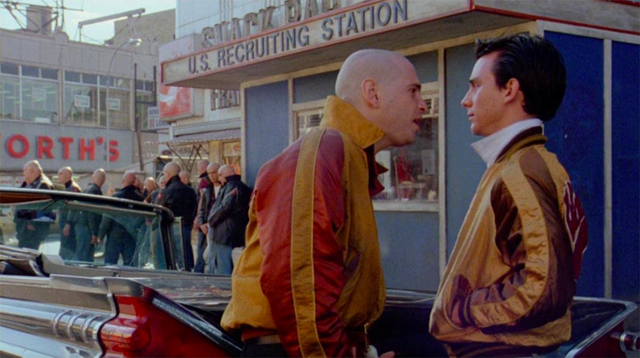

Kaufman is also at pains to make the Vietnam War loom more over his characters than it does in Price's novel. The marquee of the movie theatre we see in the first scenes of the film is playing a double bill of War is Hell (1961) and Battle Cry (1955). The pedestrian island at the corner of Grand Concourse and Fordham, where the Baldies hang out, hosts a Navy & Marine recruiting centre. (The real thing was still there in recent photos of the intersection.) One night, while drunk, the Baldies end up enlisting en masse, to the tearful distress of Peewee.

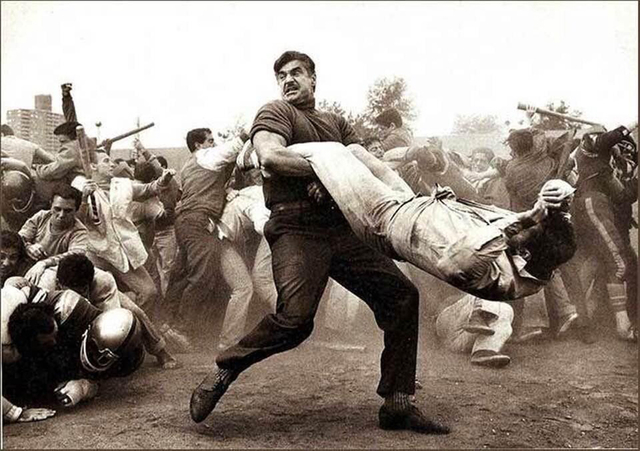

The story in Price's novel, while still loaded with generational signifiers, is a lot more generally accessible (especially, of course, if your upbringing was both urban and working class.) The movie has two big climax scenes; the first is the football game between the Wanderers and the Del-Bombers, which turns into a riot when the Ducky Boys show up out of nowhere.

While Kaufman plays it triumphantly, in Price's novel it's more like my own youthful memories of violence out in the open, in bars and taverns, on buses and subways and playgrounds – quickly escalated, randomly painful and ultimately inconclusive. For Kaufman, it's an opportunity to forge a bond between the Wongs, Wanderers and Del-Bombers, and make a hopeful gesture at his brotherhood message.

The other climax, and the big one in Price's novel, is at the stag, when somebody puts on the (covertly dark and bittersweet) Dion 45 that gave the gang its name and they all sing along:

"Joey cried as he sang. Perry felt a great mantle of sadness creep over his head and shoulders. Richie felt terrified of what he did not now...Buddy put his arms around Richie's and Joey's shoulders and squeezed tight as he could, as if the tighter he held on the more things would always be the same. Soon all of them stood with arms around each other's shoulders, rings pressing into flesh, trying to make a circle which nothing could penetrate – school, women, babies, weddings, mothers, fathers."

As Price retells it, the scene is one that many of us will remember regardless of our generation – that moment when we realized a period of our lives was about to end, and that we'd have to cope with the subsequent one without people you'd relied on up till that moment. It is, as they say today, hugely relatable, and if you squint and take away the period setting of The Wanderers, it's a lot like Saturday Night Fever, released two years previous, and a far bigger hit than Kaufman's movie.

There are some standout performances in The Wanderers; Allen is particularly memorable, as is Linda Manz, though she doesn't have nearly as much to do as in Days of Heaven (1978) or Out of the Blue (1980). Wahl and Ganios are both good, though their movie careers would end early, in 1996 and 1993 respectively. Linda Manz died in 2020.

Philip Kaufman, on the other hand, came to count The Wanderers as a minor entry in his filmography, though by 2020 it would be described as a "forgotten great coming-of-age film." He had been kicked off The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) by Clint Eastwood but rebounded two years later with a fantastic remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers. He was a co-writer on Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and hit the big time with The Right Stuff, his 1983 adaptation of Tom Wolfe's bestseller about the daredevil test pilots who led America into the Space Age, now considered one of the greatest films of the '80s.

With his wife Rose he would help create a place where art films and Hollywood could co-exist – a place that's disappeared from the map – with pictures like The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988), Henry & June (1990) and Quills (2000). Rose Kaufman died in 2009; Kaufman's last film was Hemingway & Gellhorn, made for HBO in 2012.

Ultimately, The Wanderers is a great film about memory, and how those small, painful, even sordid events of our youth loom large. As Kaufman would later tell the BBC, "When you're small, and you look at big tough guys in the neighborhood, they seem so much more monstrous and gigantic then you later realise they were when you've grown up. So, I wanted to get that sort of perspective, which is sort of reality, but is sort of – is the truth factual or is it just the way in which we experience things?"

The 100th column in Rick's Flicks will be published in two weeks, and it occurs to me that many readers might now know much about the person who writes it. If you have any questions to ask me about the column or movies or any vaguely related topic, please include them in the comments here or on the post linking here on Mark's Facebook page. Along with a special 100th column topic, I'll post answers on an Ask Me Anything feature.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.