A year ago, during the dreg ends of Covid lockdowns, I wrote a column wondering why I wasn't having any fun anymore: "I've found it hard to escape the sensation that modern life – society, culture, whatever you want to call it – is a lot less fun that it used to be, even if the circumstances of the last two years aren't taken into account."

While admitting that any pondering about absent fun is an utterly subjective activity, it was still hard to ignore the feeling that very little I was reading or seeing or even doing at this point in my life was as exciting as it once seemed to be, and that only on rare, exceptional occasions were my low expectations exceeded. When they are, I'm literally (quoting C.S. Lewis) "surprised by joy."

This is never truer than when I'm watching movies. I have, after nearly six decades, seen thousands of films – so many that I've forgotten many of them by now. At this point nearly every film I watch is seen out of curiosity, to fill a gap in my appreciation of movie history, or to revisit a picture I remember vaguely but fondly and measure its endurance. It's been a long time since I watched a film for simple pleasure – to kill an hour or two without chewing over its political, social or cultural significance.

In my mind, the last time was over three decades ago, with a film like Tremors (1990) – a low budget monster movie with a quality cast and a script that deftly balanced comedy with thrills. It was a surprise hit that became a cult film and led to five sequels, a prequel, a short-lived TV series and a failed pilot.

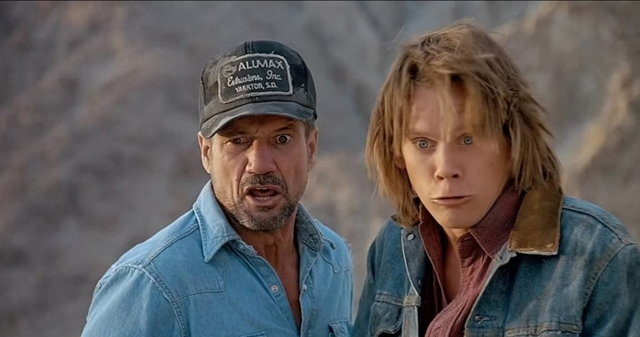

Tremors begins in bright daylight – a cloudless morning in the Nevada desert, where Val (Kevin Bacon) and Earl (Fred Ward) wake up after spending the night sleeping in the bed of their beat-up old truck. (A 1963 Jeep Gladiator J200 – the sort of truly stylish pickup that America doesn't want to make any more.)

Val and Earl are the resident handy men for the barely-there town of Perfection – a dusty cluster of bleached wood and old trailers on an old road through a valley nowhere near any interstate. It's the kind of place you go to forget or be forgotten, and Val and Earl scratch out a living doing the odd jobs that the other locals – a scant dozen, as far as the film shows us – are unwilling or unable to do: stringing barbed wire, burying garbage or building kilns for the town's hippie potter.

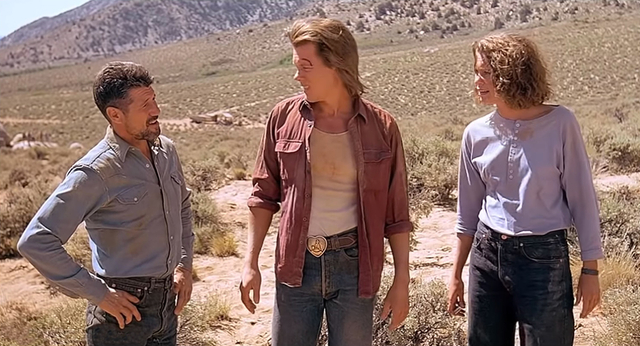

The only newcomer in Perfection is Rhonda (Finn Carter), a graduate student who apparently drew the short straw and is spending a semester monitoring seismic activity in the mountain valley. (Meant to be east of the Sierra Nevada mountains but filmed on the other side, in the Alabama Hills near Lone Pine, California – the location for countless movie westerns over decades.)

Meeting the handymen for the first time, Rhonda asks them if anyone is doing any blasting or excavation that might account for seismic anomalies she's seeing all over the valley – the first sign that something monstrous is afoot. Val and Earl drive into town and mull over their day over morning beers at the general store owned by Walter Chang (Victor Wong), bickering over their lack of a plan in life.

Apparently stuck in a rut, they're moved to break free when an accident pumping out a septic tank inspires them to load up their truck and escape to Bixby, the nearest town, but on the way they discover the dehydrated corpse of Edgar, an alcoholic old-timer, high up in a hydro transmission tower, still clutching his Winchester 30-30.

They bring Edgar's body back to town, where Jim Wallace (Conrad Bachmann), the town doctor, sends them back on the road to Bixby to get help. On the way they find the head of Old Fred (Michael Dan Wagner) next to the pulped remains of his flock of sheep, the victim of some ravenous unseen monster under the soil. A pair of construction workers fixing the road into the valley are also killed by a subterranean beast that they anger by piercing its hide with a jackhammer; while hunting them down the creature causes a rockslide that cuts off the only road out of the valley.

By this point Tremors has been mostly involved with setting the scene and populating Perfection – painting a picture of the sort of back of beyond settlement you'll find all across America's western states, from the Salton Sea past Barstow and the Mojave Desert through Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Colorado and Wyoming all the way through Montana.

They're the kinds of places you go if cities offer nothing you want, if contact with other people has to be rationed, or if you want to be as far away as possible from law or government. Edgar and Old Fred staked out their claims first, and get to be the first victims of whatever's living under the sand.

More recent inhabitants include Nancy (Charlotte Stewart), the hippie potter and single mom living in Perfection with her daughter Mindy (Ariana Richards) and Doctor Wallace and his wife Megan (Bibi Besch), living in a trailer while building their dream home under the desert stars.

And then there's Burt Gummer (Michael Gross, fresh from playing the dad on Family Ties) and his wife Heather (country star Reba McEntire in her film debut), a pair of doomsday preppers – what we called "survivalists" back in the '90s – escaping federal oversight and any oncoming calamities in their fortified compound overlooking the town.

Very few of us are suited to life on the edge or off the grid, in a forsaken place like Perfection, but I'm certain we've all fantasized briefly about holing up there at least once in our lives. I know I have, more than once, and most recently during a day spent in Cooke City, Montana, on the road between the Beartooth Pass and the northeast corner of Yellowstone National Park - an unincorporated community with a year-round population of 75, isolated from November to April when the snow falls and buries Route 212.

I can't fool myself that I'd last a single winter in Cooke City – I can barely stomach the season in Toronto – but there was an austere charm to the place and its open-carrying inhabitants, not to mention the beauty of the surrounding landscape. Maybe it's about unlimited time to read and walk; maybe it's a libertarian fantasy about living somewhere nearly unaffected by the voting choices of your fellow citizens.

Up until they're trapped in Perfection, the only glimpse the town's residents – or the audience – get of the subterranean beasties is an eyeless, snakelike creature that bursts from the ground and wraps itself around the axle of Val and Earl's truck. While trying to escape to the nearest town on horseback to get help, they're ambushed and discover that the snakes are really just the tentacle tongues of a much larger, worm-like creature that moves with incredible speed through the desert sand.

Val and Earl are on the run from the thing but manage to accidentally kill it when they jump across a drainage culvert and force the sightless thing to smash into the cement wall. Rhonda arrives on the scene to give whatever rational scientific explanation can be provided for the thing, but realizes that it isn't alone – that there at least four more of them in the valley, hunting for food.

The monsters are attracted to movement, and end up stranding the trio on a rock, but they manage to escape by pole-vaulting across the desert from rock to rock to Rhonda's truck. It's a narrow escape, but they end up drawing the beasts to downtown Perfection, trapping the survivors on the roofs of the buildings while the worm things – dubbed "graboids" by Walter, who needs to name the things to feel satisfied – circle them, learning from their feeble defenses before setting out to topple trailers and undermine their houses.

Tremors began with two words written down by screenwriters S.S. Wilson and Brent Maddock when they were working together making safety films for the U.S. Navy: "Land sharks." After they sold their script for Short Circuit (1986), their agent asked them to dig out any potential screenplay ideas they had in their files, though they had to reimagine the concept of a "land shark" because of its resemblance to a popular skit on Saturday Night Live.

The two writers ended up working on the film with first time director Ron Underwood and producer Gale Anne Hurd, ex-wife of director James Cameron and producer of The Terminator, Aliens and The Abyss. Wilson and Maddock were fortunate to end up with Underwood, a director whose talent for comedy made Tremors stand out from the usual creature features.

But they got really lucky with Hurd, whose experience with action films and sci-fi spectacle helped them put together a team that delivered practical effects that have stood the test of time, just before the advent of digital effects that would take years to fulfill their potential. Without the work that then-fledgling FX house Amalgamated Dynamics did on the picture, Tremors might have been let down either by cheesy creatures or profoundly dated computer effects.

The genesis of Tremors as a film about land sharks is obvious in scenes that echo Jaws, the greatest shark film of all time, and the model for what any wannabe summer blockbuster or drive-in/suburban multiplex hit aspires to copy. Like Jaws, Tremors succeeds as much if not more on the performances at the core of the picture, and especially Bacon and Ward's Val and Earl.

Bacon's career had really begun with his role as the suicidally reckless Fenwick in Diner (1982) before he hit stardom with Footloose (1984). Ward had been in films like Escape from Alcatraz (1979), Southern Comfort (1980) and Silkwood (1983) before playing Gus Grissom in The Right Stuff (1983). Anyone who'd watched them knew they had more to offer than just a pretty boy and a grizzled character actor, and for Tremors they created a chemistry that was more special simply because they would never team up together again for the roles in any of the sequels.

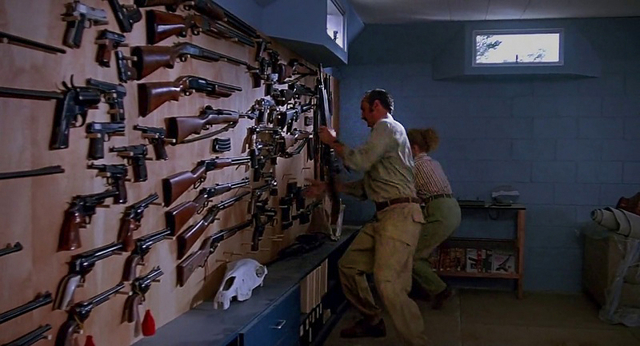

By far the best scene in the siege of the town is when the worms converge on the Gummer's compound and break through the cinder block wall of their basement workshop and arsenal. Burt and Heather are never without a weapon, and after emptying the guns in their hands into the creature, they head for the film's famous "gun wall", a display or weaponry that never fails to elicit a laugh/gasp of wonder from an audience.

They cycle through a catalogue of handguns, rifles and automatic weapons before Burt arrives at the prize of their collection: a William Moore 8-gauge "elephant gun" loaded with solid slugs made of brass rod stock. I've only seen one weapon like it in my life, and it's a marvel that Gross was able to fire it without dislocating his shoulder. (McEntire insisted on shooting the basement shootout scene with hearing protection, knowing that she'd be at least partially and likely permanently deafened by the ordnance expended in the scene.)

Overall, Tremors doesn't seem like such a terminal period piece – except for the survivalist Gummers, who end up being heroes in the story. It's been over three decades since armed, government-averse libertarian gun nuts were considered anything but dangerous subversives and potential villains; Tremors is a reminder of a time, before Ruby Ridge, when citizens who defined themselves by the Second Amendment and the distance they could get between themselves and any level of government were still tolerated in at least some adjacent province of American civil life.

You're actually allowed to feel some sympathy for Burt when the survivors attempt to escape the town in a broken trailer behind a tracked loader, as he looks with sadness on their ruined compound, musing that it had been built to withstand bombs and radiation and famine but had been done in by worms.

Part of the success of Tremors was the serendipitous collection of talents making the film, as well as its humour, economy and appropriate ambition. It didn't try to feint at anything larger than the bewildered terror of the misfit populace of Perfection; when speculating about the origin of the graboids, Val, Earl and Rhonda run through the four most likely explanations – aliens, radioactive mutants, prehistoric survivors or government-engineered weapons – before shrugging and abandoning any explanation as superfluous.

Based on each successively less satisfying installment, you can't help but wish the Alien franchise was as willing to leave the mystery of their monsters as unexplored.

Tremors was enough of a hit to lead to a series of direct-to-video sequels that began with Tremors 2: Aftershocks (1996), which brought back Ward as Early but not Bacon. Ward was gone by Tremors 3: Back to Perfection (2001), and ultimately the only consistently recurring actor in the series was Gross as fan favorite Burt Gummer, who even played his ancestor in Tremors 4: The Legend Begins, set in the frontier founding of Perfection.

Tremors: The Series aired on the Sci-Fi Channel in the spring and summer of 2003, and Kevin Bacon returned to the role of Val for an unaired pilot filmed for SyFy in 2018. Bacon said in an interview earlier this year that he's ready to sign on for a Tremors movie, as long as it isn't another straight-to-video production. And in a 2020 interview in Esquire for the film's 30th anniversary, Reba McEntire said that she'd be game to play Heather Gummer again in a movie with Bacon and Gross.

Fred Ward, sadly, died in May of 2022.

What's refreshing about Tremors – then as now – is its lack of paranoid edge or attempt at pessimistic relevance; as long as its many sequels maintained its semi-comic tone, it never succumbed to the dreaded (and by now utterly predictable) "dark reboot."

Celebrating the picture in a 2020 article on the website of fantasy/sci-fi publisher Tor Books, Joe George compares it to films like Jurassic Park (1993) and Renny Harlin's basically ridiculous Deep Blue Sea (1999), writing that "these movies were often upbeat and fun, escapist films that celebrated the strangeness of the monster instead of the vileness of humanity. In these movies, man is rarely the true monster."

"It's this portrayal of a community that distinguishes creature features of the '80s from those of the '90s," George writes. "Where The Thing was about paranoia and The Fly about a secretive outsider, movies like Jurassic Park, Anaconda, Lake Placid, and others were about groups of oddballs working together to survive the beasts that are hunting them. And while this 'let's band together!' approach may not be as darkly thought-provoking or as intellectually stimulating as the older explorations of humanity's dark side, Tremors stands as a delightful reminder that monster movies don't need to be deep to be a whole lot of fun."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.