One of the best stories from the last twenty years Hollywood history was the 2014 cyberhacking of Sony's computer network. It was credited to the "Guardians of Peace" but apparently done by North Korea in retaliation for the studio making The Interview, Evan Goldberg and Seth Rogen's black comedy that ends with Kim Jong-Un blowing up with his helicopter. It was part of a pressure campaign by the totalitarian state that at least partially worked, as Rogen and Goldberg were forced to re-edit their film's ending, while major theatre chains pulled out of screening the picture.

But that was when we were all talking about North Korea; today the Sony hack is remembered for its collateral damage. As told in Best Pick: A Journey Through Film History and the Academy Awards, the most lasting damage might have been the leaked private email conversations between Hollywood players. As recalled in the book, written by John Dorney, Jessica Regan and Tom Salinsky, co-hosts of a podcast devoted to the Oscars:

The data dumps that followed revealed damning e-mail exchanges (including one where producer Scott Rudin refers to Angelina Jolie as a 'minimally talented spoiled brat'), sensitive trade secrets and plans for various upcoming projects – but most apparent from the e-mails was Hollywood's problem with race. In one exchange, Sony executive producer Amy Pascal and producer Scott Rudin go through a list of films they think President Obama has enjoyed, joking that they were likely Lee Daniels' The Butler, Django Unchained and Ride Along.

As film critic David Thomson said about the leaked emails, "I don't think there's anything unduly shocking about it. It just shows that Hollywood is a hotbed of gossip, spite, malice – all the good stuff, you know?"

"I think it's rather more entertaining than a lot of the films Sony put out; I could have taken more of it."

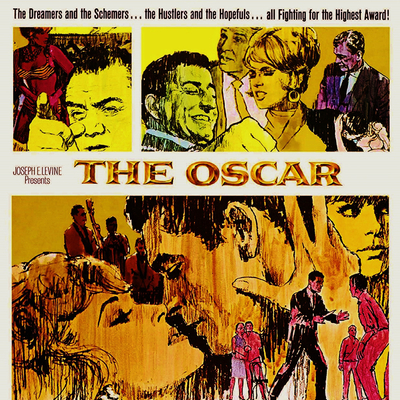

I don't think it would surprise anyone to learn that the movie industry is vicious and unseemly, and that this all comes to a head annually during the competition to win an Oscar. Why would it? Hollywood regularly spills the beans on its own scandals and backstabbing during awards season. They even made a whole film about it in 1966, and as bad as that film is, it's certainly preferable to sitting through however many interminable hours of the awards ceremony they'll broadcast this weekend.

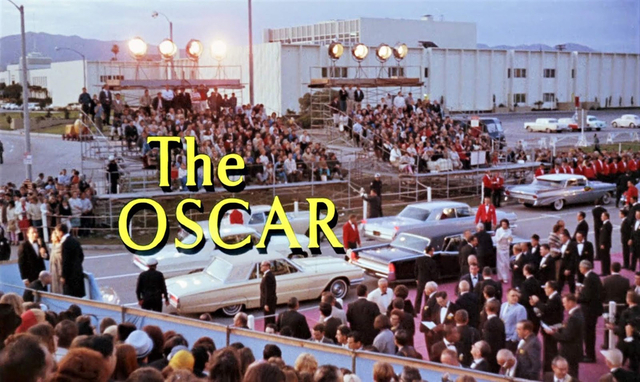

The Oscar was directed by Russell Rouse, a writer, producer and director whose credits include D.O.A., New York Confidential and Pillow Talk, and begins on the red carpet of an actual Oscars ceremony at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, home of the awards for most of the '60s. It's a big night for Frankie Fane (Stephen Boyd), who's up for the Best Actor award. While Bob Hope begins his ritual self-deprecatory opening speech, the camera rests on Hymie Kelly (Tony Bennett), Frankie's best friend, who informs us in a voiceover that the actor is "on top of a glass mountain" that they've painfully climbed, and so the flashbacks begin.

Back east Frankie was a "spieler" for his stripper girlfriend Laurel (Jill St. John), with Hymie as his wingman. When a bar owner chisels them out of their payment Frankie lays him out and the trio try and fail to outrun the corrupt sheriff (Broderick Crawford) who runs the town – and partners with the bar owner. He takes their money and puts them up on charges like procuring and prostitution, and hints that he'll let them skip if they can come up with bail money, which they can only manage by selling Laurel's car.

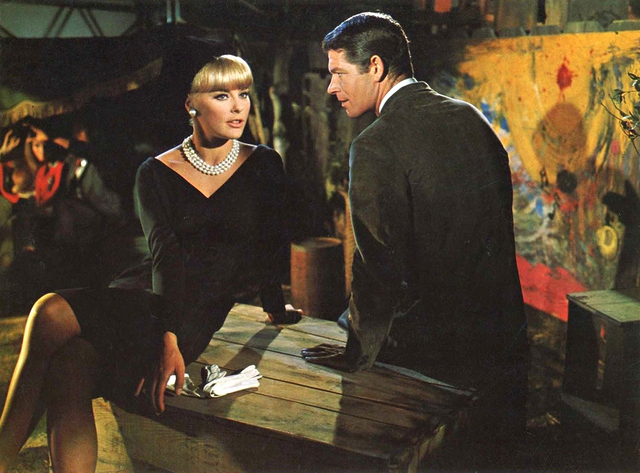

They hitch to New York, where Frankie is happy enough to live off Laurel's earnings until he and Hymie meet Kay (Elke Sommer), an aspiring costume designer, at a beatnik party in the Village. He dumps Laurel, who's pregnant with his child, and Kay gets him a job in the garment district. While tagging along to the rehearsal of a play, Frankie catches the attention of Sophie (Eleanor Parker), a talent scout, when he derides the knife-fighting skills of the actors and steps onstage to forcefully show them how a real thug handles a switchblade.

Sophie likes what she sees – whether it's a glimpse of talent or Frankie's animalism – and gets him a Hollywood agent, Kappy Kapstetter (Milton Berle, and no, I'm not making up the character's name). Kappy talks Regan (Joseph Cotten), a studio head, into signing Frankie, who sends for Hymie to fly out and be his personal assistant, as even a rising bit player can make enough money to hire an entourage.

On his way up Frankie has to deal with sundry humiliations, like sitting quietly in the corner of Regan's office while the studio boss talks about him like he's a piece of meat, or being assigned as arm candy for the studio's bossy blonde bombshell, Cheryl Barker (Jean Hale) – a nasty caricature of Carroll Baker apparently shoe-horned into the film by its executive producer, Joseph E. Levine, who had fought with Baker while making Harlow.

Hollywood might think they're tough, but they're no match for Frankie, who revisits every humiliation back on them as he rises up the marquee. He upgrades from a pad in a swinging garden apartment to a yacht, a Rolls Royce and a big house, adding a valet (Jack Soo) to his staff on the way.

"Even Sam the houseboy was imported," Hymie tells us in the voiceover. Yes, that's an actual line.

Near the peak of his stardom he notices Kay on the studio lot talking with Edith Head (who did the costumes for The Oscar). He gets Kappy to pressure Regan to get her promoted to designer; overcome by his generosity, she ignores her instincts and accompanies him to the bullfights in Tijuana.

You have a nagging feeling that Rouse is attempting comedy during discrete moments in his film, and the closest he comes is when Frankie and Kay meet another American couple in Mexico. Barney and Trina Yale (Ernest Borgnine and Edie Adams) are a lowbrow pair, but Trina is a big fan of Frankie's, and they reluctantly agree to be their witnesses at the quickie ceremony they're in Mexico for – what Kay mistakenly thinks is a wedding, but turns out to be a Tijuana divorce.

For some reasons the whole trip – Mexico, the bullfights, the Yales – puts Frankie in a mood to ask Kay to marry him, which sends both couples back to the same gouging officiant who divorced the Yales. I'm sure this whole section of the film was supposed to be wacky and madcap, in the style of so many '60s studio comedies, but it can't fight its way out of the film's baroque sourness – nothing could.

The Oscar was so notorious that it was unavailable on DVD or Blu-ray for many years, a scrap of (I hope) unintentional high camp that was only celebrated by fans of "so bad it's good" cinema. I could rhapsodize about its failings, but I'd prefer to quote Ken Anderson, my online film critic colleague, on his essential Dreams Are What Le Cinema is For blog, where gets started by calling it "one of the most sublimely terrible movies ever to grace the screen":

"With nary an ironic or self-aware bone in its bathetic, threadbare body, The Oscar is the kind of pandering-yet-earnest, self-serious Hollywood trash no one has the old-school, out-of-touch naiveté to know how to make anymore. A 1966 film that would have felt warmed-over in 1960 (the year Ocean's Eleven and Sinatra's Rat Pack made this kind of clean-cut, pomaded, sharkskin suited, ring-a-ding-ding brand of cool into a veritable brand), The Oscar is from the Joseph E. Levine (The Carpetbaggers, Harlow) school of overlit, elephantine artifice. Every interior looks like a soundstage, everyone's clothes look as though they've never been worn before, and the characters are so lacquered and buffed they resemble department store mannequins."

Ken writes that it's hard to pick out the worst performance in the film, especially when nearly every scene features Boyd's "bellowing, bombastic over-emoting" but Tony Bennett's Hymie is particularly awful. As a huge fan of Bennett it pains me to write this, but his glum, hangdog expression never lets up from what Ken calls a "Boo Boo Bear blandness."

The story is relentlessly sordid, from Parker's Sophie-the-cougar (described by another character as "You, you're 42. There aren't many good minutes left for you.") to Berle's Kappy, who admits mere moments after we meet him that he spends a good chunk of his agent's fees on "ladies of the evening." Berle's is one of the few performances that manages to avoid being overplayed; Ken writes that his Kappy is "out of an SCTV Bobby Bittman sketch...so low-wattage as to barely register at all."

Jack Soo emerges from The Oscar nearly unscathed, mostly by acting like he's in another film altogether, or anticipating some Barney Miller episode waiting in his future.

"When I watch The Oscar I always wonder: was this a movie pandering to star-struck yokels and serving up a patently false, fan-magazine/press agent image of Tinseltown because it believed that's what they wanted to see?" writes Ken. "Or had years of lying to itself deluded 'The Industry' into believing its own publicity? This can't be how '60s Hollywood actually saw itself, can it?"

The Oscar was based on a novel by Richard Sale, a writer of pulp fiction and screenplays as well as the director of Let's Make it Legal (1951), which featured an early screen appearance by Marilyn Monroe, and Gentlemen Marry Brunettes, the 1955 sequel to Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, which starred Jane Russell but not Monroe. Sale was obviously no Hollywood outsider with a grudge, which makes Ken's question even more pointed.

The script is full of hypertrophied dialogue that verges on surreal, even meaningless, when it isn't trying to sound like hard-bitten hipster banter. (Frankie: "You a tourist or a native?" Kay: "Take one from column A and two from column B and get an egg roll either way." What now?) That was the work of three people, with none other than Harlan Ellison getting top billing over Rouse and his regular screenwriting partner, Clarence Greene.

Ellison was a legend in screenwriting circles, famous for his speculative sci-fi stories as well as scripts for TV shows like The Outer Limits ("Demon with a Glass Hand" and "Soldier") and Star Trek ("The City on the Edge of Forever"). He was also famously combative, constantly threatening and issuing lawsuits and sending belligerent letters to anyone he felt had maligned him or his reputation.

I was once on the receiving end of Ellison's rage. After writing what I thought was a flattering passage about him in a column, I received an email from his spokesperson (Ellison was a sci-fi writer who famously hated the internet) dutifully quoting Ellison's angry criticism of not just what I'd said but what he thought I had inferred. I have no idea how my column would have made it to him without a very efficient clipping service, but Ellison's angry letters were such a legend at this point that it felt like an honour to get one.

Frankie's career hits the skids when he pulls one too many power plays on his studio just when he becomes "box office poison." He's bottomed out, on the verge of accepting a (gasp) TV pilot when news comes through that a bad guy turn in a hardboiled picture has turned into a Best Actor nomination.

While Hymie runs his conventional campaign for the award – full page ads in the trades, buttering up the movie press – Frankie decides that he has nothing to lose and, with private detective Barney Yale as his covert operative, leaks his arrest at the start of the picture to the papers, reasoning that if he makes it look like the other nominees have pulled a dirty trick on him (Richard Burton and Burt Lancaster are name-checked) he'll be able to make a sympathy play.

"I can't rig the votes," he tells Hymie, "but I can rig the emotions of the voters."

The relentless and expensive campaigning for both Oscar nominations and votes is a well-known fact in Hollywood. Best Pick recalls John Wayne's epic campaign to save The Alamo from losing money by spending a million dollars of his own money on top of the $3 million he put into its then-lavish $12 million budget.

Wayne "campaigned like a man possessed" with a press release "running to an insane 183 pages", forty-three ads in the trades and even an endorsement from no less than John Ford, calling The Alamo "the most important picture ever made. It is timeless. It will run forever." When Chill Wills got a nomination for Best Supporting Actor he began his own campaign, "which threatened to eclipse John Wayne's in its zeal and vulgarity." The Alamo ended up winning just a single Oscar for sound and put Wayne's finances in peril for the rest of his life.

The onetime masters of Oscars campaigning were the Weinstein brothers and Miramax. In 1995 they garnered five nominations for Il Postino, an Italian film, with a campaign that involved "sending out five thousand screeners and soundtrack CDs, organizing poetry recitals, and publishing trade ads throwing Italy's film commission under the bus for refusing to submit a film directed by an Englishman. However, the real reason they didn't submit the film was that it had already been released in Italy the previous year, and so it was no longer eligible."

This year's awards campaign scandal is the nomination of British actress Andrea Riseborough, for her role in To Leslie, a low-budget independent film that has no other nominations. Riseborough got nominated thanks to a grassroots write-in campaign organized by Michael Morris, the film's director, and his wife, actress Mary McCormack.

A network that included Kate Winslet, Jane Fonda, Edward Norton, Gwyneth Paltrow, Courtney Cox and Charlize Theron hosted screenings, talked it up on podcasts and wrote social media posts that suggested either a wellspring of peers in Riseborough's corner or a sly internet campaign that encouraged cut-and-paste Twitter blurbs to get the votes out.

Considering how an Oscars campaign can cost at least $15 million these days and needs to adhere to strict Academy rules, the nomination announcement caused an explosion of speculation about the legitimacy of Riseborough's nomination, how the process stacks the deck against small pictures – and systemic Hollywood racism squeezing out nominees like Viola Davis and Danielle Deadwyler. Don't expect any of this to go away this weekend if Riseborough wins.

If Frankie Fane was a real person, he'd have been up against Paul Scofield, Alan Arkin, Richard Burton, Michael Caine and Steve McQueen at the Oscars. (Scofield won.) If The Oscar had stood a chance in hell of being nominated, it would have competed against A Man for All Seasons, Alfie, The Russians are Coming, the Russians are Coming, The Sand Pebbles and Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? In this context, The Oscar's whole compromised view of the industry doesn't seem so outlandish, especially since the fictional Frankie really was nominated alongside Burton.

Frankie might be a despicable heel, but nobody would say that no one who resembles him has ever been nominated or won. (Harvey Weinstein was nominated twice and won once – but was responsible for over eighty wins over his career. He had a lot of gratitude protecting him.)

After he gives an Oscar-worthy performance for the press, Frankie's chances are good, at least until Barney Yale turns blackmailer and threatens to blow the whistle on him. Frankie almost convinces Hymie to help him kill Yale, but he finally digs up the detective's ex-wife and gets her to tell him about the cash he's been hiding from the IRS.

At the end almost everybody from Yale up thinks that the ruthless Frankie has what it takes to win an Oscar except for Regan, the studio head, who throws a party for him despite seeing through his devious ploy for sympathy. "The Oscar means a great deal to me," he tells Frankie, "and I don't like to see it tarnished."

Back at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium Frankie is alone but certain that he's won – so much so that he rises to accept his statuette when Merle Oberon begins announcing the winner. His face crumples when she reads "Frank....Sinatra," and the camera darts around to take in the satisfaction of everyone who knows Frankie and can enjoy his humiliation. The Chairman of the Board kisses his daughter Nancy and runs up to accept his Oscar while Frankie shrinks and crumples back into his seat while the whole audience rises to applaud.

When you think about it, nobody would have been surprised if Sinatra had been behind a smear campaign against Frankie. And they still would have voted for him, if only out of fear or grudging respect. Because even in a fictional Hollywood as outlandish as The Oscar, it's still apparently Frank's world.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.