When Germany finally surrendered in the spring of 1945, one of the immediate problems Allied occupiers and provisional governments had to deal with was reprisals against former occupiers, collaborators and sympathizers. Revenge had begun even before the first Allied tanks and jeeps had rolled through liberated towns, and it was a problem General Charles de Gaulle, now the leader of France, had to deal with.

As Ian Buruma writes in his book Year Zero: The History of 1945, "de Gaulle disapproved of this sort of thing; only the state should have the right to punish." He had a number of former members of the resistance arrested for showing "excessive zeal" in killing suspected collaborators, but as Pascal Copeau, a journalist and resistance leader, wrote to de Gaulle in a letter in January of 1945:

"During four terrible years the best of the French learned to kill, to assassinate, to sabotage, to derail trains, sometimes to pillage and always to disobey what they were told was the law...Who taught these Frenchman, who gave them the order to assassinate? Who if not you, mon général?"

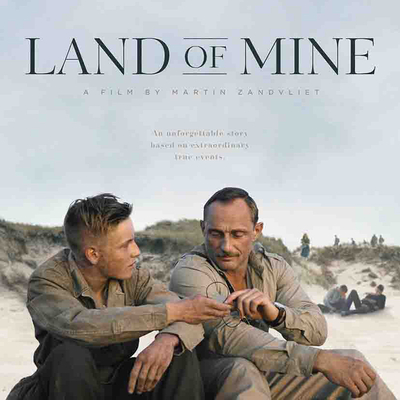

Land of Mine, the 2015 war film nominated for that year's Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, deals with this precarious moment, albeit in another liberated country. Set in May of 1945, just after the German surrender, it's the story of Minekommando Dänemark: units of Wehrmacht prisoners of war given the task of clearing and defusing the minefields laid by the German army along the Danish coastline, on the northernmost stretch of Hitler's Atlantic Wall.

The movie begins with lines of disarmed German troops marching along a dirt road by the Danish coast. A man in a jeep drives by them, scrutinizing the long column of dispirited men. Sergeant Carl Rasmussen (Roland Møller) is wearing the uniform of a British paratroop, with an armband indicating that he's a Danish national, seconded into his country's armed forces after fighting his way back to his homeland.

Rasmussen picks out a soldier carrying a Danish flag and beats him savagely, taking away the man's souvenir. "Denmark is not your friend," he bellows at the defeated Germans. "No one wants to see you here." His uniform signifies that he's paid for the right to abuse the men who invaded his country and lost. This is all the backstory writer and director Martin Zandvliet gives to Rasmussen; there's no anecdotes about lost friends, estranged wife or family, perilous escape across the sea or time in service to the Allies. There's an austerity and economy to Land of Mine that's equally audacious and, ultimately, distancing.

British paratroops were in fact the first Allied soldiers to enter Denmark after the German surrender, and Canadian paratroops were ultimately the country's postwar salvation, with crack units of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion racing to occupy Wismar on the German coastline in advance of Soviet forces, who had been given the right to occupy Germany up to this point along the Baltic coast at the Yalta Conference. Churchill and other Allied leaders worried that, given the weakness of Nazi resistance at this point in the war, after Hitler's suicide in Berlin, the Soviets were likely to sweep all the way to Denmark, adding another European country to their growing collection of puppet states.

There was a tense standoff between British and Canadian paratroops and the Soviets that occasionally turned violent – one of hundreds of rarely-told stories about the anxious situation as the war shuddered to a halt. But the line held long enough for the Allies to consolidate the territory behind them and make good on Churchill's promise to Denmark's government in exile that the British would be the ones to liberate their country.

Rasmussen, played by Møller as a man of precise habits that barely paper over concealed anguish, arrives at the shore and begins pacing out lines in the sand, hammering in stakes with black flags while he consults a map. Shortly after a truck pulls up, its contents a dozen or so boys in motley Wehrmacht uniforms. They are to be his command – a tiny fraction of the over 2,000 German prisoners of war re-classified as Surrendered Enemy Personnel rather than POWs to provide manpower for the massive minefield clearances that had to be carried out on the Danish coast.

The boys are given cursory training in digging up and defusing the wide variety of landmines and booby traps left behind – over 1.4 million anti-tank and anti-personnel mines littering the coast from Fanø Island to Hirtshals. The boys have to clear 45,000 mines at a rate of six mines an hour before they can go home. Their first casualty dies during training, under the indifferent and contemptuous eye of Captain Jensen (Mikkel Boe Følsgaard), Rasmussen's commanding officer.

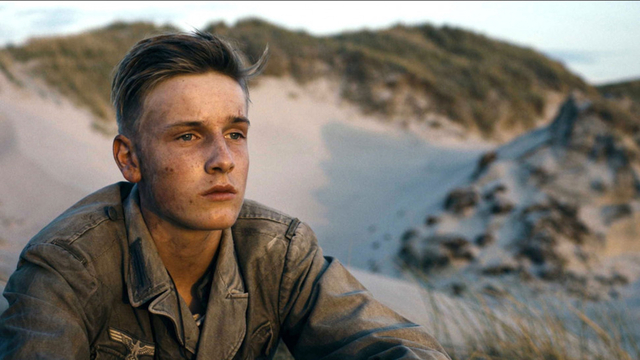

At first it's hard to differentiate between the boys in their oversized combat fatigues, faces hidden by huge steel helmets. Eventually we pick out a quintet of frightened and demoralized young men behind the dirt-smeared faces – a group that's reduced to a quartet suddenly when Wilhelm (Leon Seidel), the optimist of the group, has his arms blown off by a mine, dying in the hospital not long after.

Helmut (Joel Basman) is the technical leader of the group, slightly outranking the rest and the only one who's seen real combat. But Sebastian (Louis Hoffman) emerges as their moral leader, the only one who can keep his focus on completing their task and fulfilling their end of Rasmussen's promise that, once done, they can go home. Conflict between the two boys is inevitable.

But the film also focuses on Ernst and Werner, twin brothers played by Emil and Oskar Belton. They seem to be the youngest soldiers in the group, barely in their teens, the most visible example of how desperately Nazi Germany had been trying to plug holes in its rapidly depleting ranks in the final year of the war they'd lost long beforehand.

The boys survive by relying on each other and a collection of rituals and phrases they recite together, capturing and naming insects and other tiny beach wildlife; deprived of their families, unable to rely on the other boys for solace, they try to create a tiny, pathetic perimeter of emotional refuge for themselves. Their relationship is the most heartbreaking aspect of Zandvliet's film.

Rasmussen's anger at the defeated German occupiers transfers easily to the dozen boys under his command. He shrugs when they complain that they haven't been fed – he tells them that the whole country is starving, and their needs are at the bottom of the list – and locks them into a shed in the dunes at night.

But boys are resourceful, and Helmut finds a loose board and escapes during the night, heading out to scavenge for food for "his" men. The only thing he can provide is animal feed, stolen from the barn of a Danish woman – we assume she's a widow, or waiting for a husband who might not come home – who lives with her daughter nearby.

But the grain is contaminated with rat feces and the boys become violently sick. When Rasmussen questions the woman and discovers the cause, her only reaction is a wan smile as she tells him that "I finally got some Germans after all."

Rasmussen makes the boys quaff seawater to make them vomit out the poison, and shortly after steals some provisions from the nearby Allied base – a sign of mercy noted by Jensen, who retaliates by bringing a group of British soldiers to terrorize the boys late one night, beating them and urinating on one boy they force to the ground.

Jensen is the closest thing the film has to a villain, a military bureaucrat who takes the same bloodless pleasure in inflicting pain under the cover of policy and orders that's normally assigned to the concentration camp kommandant or SS Obersturmbannführer in most war pictures. It's an interesting shift that says a lot about making a movie about World War Two nearly 80 years after that war ended.

Denmark's history as an occupied country began with the Six Hour War, when German troops invaded Denmark and Norway in April of 1940 and quickly overpowered their tiny army. Denmark had peculiar status among occupied European territory: unlike the monarchs of Holland and Norway, King Christian X of Denmark stayed in the country during the occupation, becoming a symbol of resistance.

Crackpot Nazi racial theory designated the Danes kindred Aryans, so the Germans initially treated Denmark as a protectorate and let the Danes govern themselves until 1943, when strikes and resistance intensified during a general election and the country was put under direct Nazi control. On the surface Denmark was like many countries occupied by Germany, with stories of cooperation and collaboration and resistance, both passive and militant.

What distinguished the country was the apparently spontaneous rescue of its Jewish population, the vast majority of whom were secreted out of Denmark to neutral Sweden just before the Nazis could begin their mass deportation in October of 1943. By comparison, seventy-five per cent of the Jews in nearby Holland didn't survive the war; Denmark's Jewish rescue gave it rare moral stature in postwar Europe and is frequently celebrated, even in videos made by the Viking cruise line.

The rescue of Denmark's Jews was told in The Only Way, a 1970 film starring Jane Seymour, and in Miracle at Midnight, a 1998 TV movie featuring Sam Waterston and Mia Farrow. And director Robert Aldrich made Ten Seconds to Hell in 1959, a melodrama about German soldiers working on a bomb disposal squad in Berlin after the war, starring Jeff Chandler and Jack Palance and co-produced by Hammer Studios and UFA.

But Europeans have recently discovered a new appetite for telling stories about their countries during the war. Norway made the excellent The King's Choice (2016), about the escape of King Haakon VII and the royal family during the German invasion, and Narvik (2022) recently started airing on Netflix – a movie set during fighting for the Arctic port town in 1940. The Forgotten Battle (2020), a Dutch film about the Battle of the Scheldt in 1944, also debuted on Netflix in 2021.

Omvej til friheden (1969) was a Danish TV movie about Danish Jews escaping to Sweden, and The Boys from St. Petri was a 1991 fictional film based on the "Churchill Club," a group of schoolboy saboteurs who inspired a book series and several novels, including the one by Bjarne Reuters that was the basis for the movie. But Danish interest in its war stories was really revived in 2008 with Flame and Citron, a film about two legendary Danish resistance fighters and assassins starring Mads Mikkelsen.

Hvidsten gruppen was a 2012 film about the Hvidsten group of resistance fighters, released in English as This Life, and its popularity led to a sequel in 2021 - Hvidsten gruppen 2, also known as The Bereaved. April 9th (2015) told the story of the Six Hour War, and starred Mads Mikkelson's brother Lars and Pilou Asbæk – better known here as Euron Greyjoy in Game of Thrones.

In 2022 Netflix began streaming The Bombardment (2021), a film about the final months of Nazi occupation and Operation Carthage, an RAF air raid that accidentally bombed a Catholic school in Copenhagen. Ole Bornedale, the director of The Bombardment, also made 1864, a 2014 Danish TV miniseries (also starring Pilou Asbæk) about the disastrous war between the Danes and Prussia that's considered one of the key 19th century conflicts that inevitably led to World War One.

What ties all these films together is rather excellent production and costume design and superb visual effects that depict wartime Europe with what seems like stunning accuracy. They also take pains to depict the grey areas and moral equivalency of war, with stories that pointedly portray the cost on civilians, and their suffering and death as collateral damage.

In Land of Mine, it's hard to interpret the death of the boys in Rasmussen's demining squad as collateral damage, inasmuch as the regular loss of personnel in the Minekommando Dänemark seems to be considered a covertly welcome inevitability – a feature, not a bug, at least for someone like Jensen. Werner is killed when he tries to defuse a booby-trapped mine – two mines on top of each other, connected by a trigger wire.

The boy disappears in a cloud of flame and sand, with so little left that his brother becomes obsessed with searching for him, sure that he'd managed to run away before the mine exploded. It's a pitiless death, and it's the one that director Zandvliet makes us feel the most – well, at least until Rasmussen's dog is killed when it runs over a mine the boys have missed, just as the older man has softened up enough to take a paternal interest in the boys, giving them a day off and playing soccer with them on the cleared parts of the beach.

The dog's death reawakens his anger, and he humiliates the boy he considers responsible before forcing all of them to link arms and walk in a line across minefields they've recently cleared, to prove they've done their job.

There's plenty of historical precedent for this: an article on mine clearance in Denmark after the war published by Roly Evans in the The Journal for Conventional Weapons Destruction has a photo of Minekommando Dänemark personnel walking a minefield, and notes that it was common in Europe after mine clearance, with locals invited to watch, to prove that their land was now safe.

"The clearance of Denmark was costly, as was recognized at the time," writes Evans. "In December 1945, Dansk Minekrontrol listed 149 dead, 165 severely injured, and 167 lightly injured during the demining effort. While the total workforce was not static, Dansk Minekrontrol calculated that 20 percent of all deminers were either killed or injured." Evans goes on to note that the Danes were eager to compare their statistics favorably to demining efforts elsewhere, like in France "where it was claimed that 1,000 deminers were killed and 1,000 were injured for every million mines cleared."

The clearance of Denmark's minefields was considered a great success, thanks to the precision of the Germans who did the work – both the maps they'd made when they laid the mines and their thoroughness when clearing them – and the speed with which it was accomplished. Still, nothing on this scale can be perfect, and while Land of Mine was filming in authentic locations in Jutland in 2014, an unexploded mine was discovered in the sand.

Zandvliet is more relentless in his story; the majority of Rasmussen's demining squad die in a massive detonation when a still-live mine is accidentally piled into the back of a truck loaded with them. He's left with just four boys, and he discovers that Jensen has undone his promise by re-assigning them to clear mines in a new area where the minefield has shifted and fatalities will be much worse.

Rasmussen steals a truck and forges orders, retrieving the remaining boys - which includes Sebastian and Helmut – and driving them to fifty metres from the German border. He tells them to run. Zandvliet was at pains to note during a post-screening talk filmed as a bonus feature for the film's DVD release that no such thing ever happened in real life.

Much of the praise for Land of Mine describes it as a powerful story, but I found it flat and dramatically undistinguished, partly thanks to the taut, utilitarian tone of Zandvliet's storytelling. Perhaps in the first decades of the 21st century, decades after the end of World War Two and when so few people with vivid, lived memories of the war are around, it helps evoke a more catastrophic world, where hardship and loss were more broadly experienced, and moral choices were made when stakes and consequences were so much more stark.

I can't help but compare it unfavorably with, say, Roberto Rossellini's War Trilogy – Rome, Open City (1945), Paisà (1946) and Germany, Year Zero (1948) – some of which were filmed in the rubble of the war, and even when they flirt with melodrama have a rawness and immediacy that wasn't possible even a few years later. Or films like Rene Clement's Battle of the Rails (1946) or the West German film The Bridge (1959), made by and with people who could compare the material with their own memories. Even a chestnut like The Cruel Sea (1953) has resonance, a story about trauma, echoing great, recent events that transformed millions of lives.

As hard as we might try to imagine life during wartime from the perspective of societies that have lived in peace for generations, even our most earnest efforts feel unearned, and not even excellent production design and effects can distract from a nagging sense that we're just watching superb and expensive role-playing. On one hand this is a criticism; on the other hand I'm not sure most of us would like to return to a time when authenticity can be acquired more easily.

I have a maxim that there is no such thing as a period film: no matter the era or setting, a film is about the time when it is made, imbued with the biases and preoccupations of the filmmakers in their historical moment. To prove this point, in the filmed interview with Zandvliet on my DVD of Land of Mine, the director says that much of his inspiration for the movie was the Syrian refugee crisis in Europe and growing popular opposition in Denmark to taking in refugees. His film, up to and including its title, was about the dangers of nationalism. (The English translation, Land of Mine, was closer to his original intention than a literal translation of Under sandet, the Dutch title: Under the Sand.)

How he squared this with his ending – admittedly imagined rather than historical – with four German boys escaping back into their country with the aid and approval of their Danish "captor", isn't something he explained, though. The analogy, no matter how seriously intended, simply don't make itself obvious. Perhaps, in trying to make 1945 like 2014, he prevented himself from seeing what made that distant moment unique, and made the popular error of mistaking resonance for relevance.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.