Ernst Lubitsch was divorcing his second (and last) wife Vivian when he was shooting Heaven Can Wait, his first film for Daryl F. Zanuck at 20th Century Fox. The problem wasn't Lubitsch's infidelities – though there were a lot of them – but his workaholic tendencies and neglect of his wife, at least according to her petition for divorce on grounds of cruelty.

The director's niece Ruth Hall later said "I don't think he was a marrying man; I think she wanted to make him a real husband and he liked to be with his cronies." Having failed at this task, Vivian would get her decree a year later, receiving a lump sum of $28,500, a percentage of his earning in monthly alimony ($3,709.22 according to probate records) and $150 a month in child support for their daughter Nicola.

According to Scott Eyman in his biography Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise, the director "returned to his bachelor ways."

"He was constantly interested in these sorts of sexpots," remembered his former assistant director Gottfried Reinhardt, son of the famed Viennese theatre director Max Reinhardt. "None of them very young or attractive. He had a carelessness about sex. Ernst Lubitsch had only one interest: films. Then he rode horseback and he got massages and he went fucking. He did these things secondarily. There was really nothing in his life but movies."

Perhaps not surprisingly, Heaven Can Wait is the portrait of a charming womanizer, a man of wealth and means who scandalizes his family and afflicts his long-suffering wife with his infidelities. Henry Van Cleve was a born at a fine address in the prelude to Manhattan's Gilded Age, the apple of his mother and grandmother's eye, and a source of constant bafflement to his starchy dullard of a father. But before his story begins we meet him in Hell.

Henry (Don Ameche) is an elegant but subdued old man when he walks slowly down the long steps between two huge red columns into the office of "His Excellency" – Satan as played by Laird Cregar, huge and imposing in his swallowtail coat and goatee. Henry is resigned to being there, and while the office of the lord of the underworld is a pleasant enough place, His Excellency courteous and well-mannered, it's only the antechamber, and the next destination is much worse.

But before he's sent along, Satan wants to know what he thinks he's done to deserve eternal damnation. "I have no illusions," says Van Cleve. "I know the life I've lived." That's fine, replies Satan, but what particular crimes has he committed?

"A passport to Hell isn't issued on generalities."

If Lubitsch projected much of himself onto his movie's "hero," he's also at pains to imagine Satan as not unsympathetic to men who show up in his office assuming they're beyond saving – while hoping deep down that they might still be worth redemption. Lubitsch films are very much places that Lubitsch could imagine inhabiting, and both Satan and Van Cleve share a fondness for beauty and an aversion to the fake and unattractive.

"Throughout the film," writes Eyman, "Lubitsch belittles only priggishness and unsightly vanity; an old woman displaying her varicose-veined legs to His Excellency prompts him to instantly hit the trap door, consigning her to a screaming hell." Early in the film we get a glimpse of the occasional cruelty that hid like thorns beneath the lushness and charm of Lubitsch world.

The story of Henry's life is the story of the women he has known, starting with his mother and grandmother and proceeding through to Mademoiselle, his French governess (Signe Hasso, who was actually Swedish). More worldly than his American family, she sees the man struggling to emerge behind the boy.

"His soul," she says, "is bigger than his pants," a classic Lubitsch line that ruefully swipes at the potential censors overseeing the Production Code against which he lazily struggled during his whole Hollywood career.

Henry's roguish tendencies are a trial for his parents; his mother (Spring Byington) is constantly asking "Where does he get it from?" It's obvious to us that he gets it from his grandfather Hugo, played with huge appeal by Charles Coburn, who sees in the boy everything he wanted to be and do but never had the chance.

"Yet, while Henry thinks he always gets his way," Eyman writes, "throughout the film women tend to control him. His subterfuges are obvious, his infidelities, either actual or attempted – the film goes a little vague about specifics – are rather charmingly pokey. He is an early example of the species Boy/Man and Lubitsch is equally fond of both aspects, a partiality he passes on to most of the female characters."

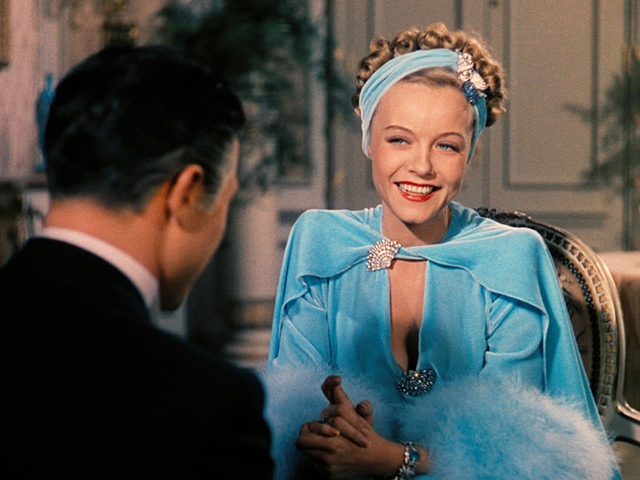

The most important woman in his life is Martha (Gene Tierney), the daughter of a midwestern meat magnate and his hawk-faced wife (Eugene Pallette and Marjorie Main, two more character actors who fill out the film magnificently.) He meets her in Wannamaker's department store and follows her to Brentano's bookshop, where he pretends he's a sales clerk to obtain her address.

Unbeknownst to him, she's in town with her parents to introduce herself to his family, as she's the fiancée of his cousin Albert (Allyn Joslyn), intensely tedious and dull but her ticket out of Kansas City - the first suitor who ever managed to get the approval of both of her perpetually bickering parents.

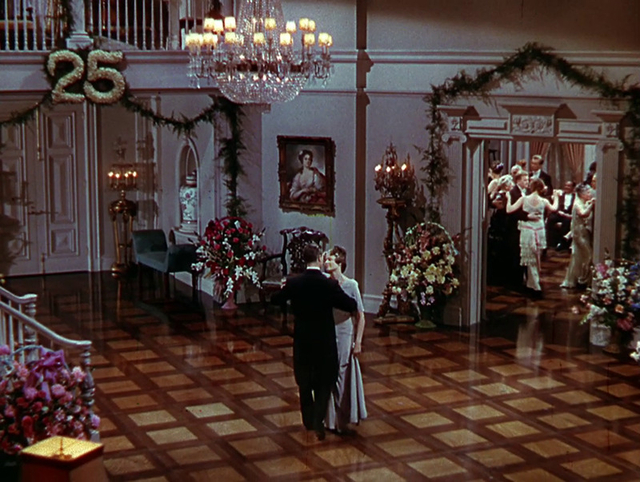

She wants to buy a book titled "How to Make Your Husband Happy"; he wants her to forget about that and run off with him. At a celebration of Henry's 26th birthday (the whole film is structured around Henry's birthdays) he convinces her to elope, scandalizing both their families. It will only be years later, at his 50th birthday, their 25th anniversary and just a year before she dies, the she finally tells him that her tortured reluctance on that fateful night was all a show.

Whatever sins he might think he committed, Henry is rarely if ever the master of his own destiny.

Besides being his first film for Fox, Heaven Can Wait was also Lubitsch's first film in Technicolor. Neither seemed to have done anything to alter the director's course or worldview, and with scriptwriter Samson Raphaelson working with him – the two had worked together on The Smiling Lieutenant (1931), Broken Lullaby (1932), One Hour With You (1932), Trouble in Paradise (1932), The Merry Widow (1934), Angel (1937) and The Shop Around the Corner (1940) – it's considered one of his best films, even his last really great one.

The writer had a major Broadway success with The Jazz Singer, which he'd dictated in sequence over the course of a single weekend and, when it was adapted into the landmark talkie in 1927, became his entrée into Hollywood. Raphaelson wasn't much loved by Lubitsch's wife and had been persona non grata, but upon Lubitsch's separation from Vivian, the two men were able to work together again at the director's home, which Raphaelson would later call "a blithe experience".

The film was also made in the middle of America's war, amidst an avalanche of features and propaganda telling stories of the battlefront and the home front. The year's films include Edge of Darkness, Destination Tokyo, Action in the North Atlantic, Crash Dive, The Moon is Down, First Comes Courage, Assignment in Brittany, Minesweeper, Sahara, Immortal Sergeant, Air Force, Guadalcanal Diary, Watch on the Rhine, Salute to the Marines, Tonight We Raid Calais, This is the Army, Reveille with Beverly, So Proudly We Hail, Bombardier, We've Never Been Licked, The North Star, Swing Shift Maisie, We Dive at Dawn, Mission to Moscow, Hitler's Children, Hitler's Madmen and The Strange Death of Adolf Hitler.

While personally invested in helping with the war effort, the closest Lubitsch came to producing any kind of war content (besides To Be Or Not To Be, the last comedy he'd direct before joining Fox) was a propaganda film he made for Frank Capra's production unit at the Department of War. Know Your Enemy: Germany was shot in a week in the fall of 1942 on standing sets on the Fox back lot and never released, though some shots ended up being used in Here is Germany, a 1945 propaganda picture made by Gottfried Reinhardt, Anthony Veiller (The Killers, Beat the Devil) and William L. Shirer (author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich).

Lubitsch's major contribution was probably volunteering as an air raid warden, which must have struck the director as an essentially absurd job in Los Angeles, and one that produced a priceless comic anecdote, recalled by Scott Eyman in his biography of Lubitsch:

One night he was making the rounds during a blackout. Noticing a light on at (writer and director) Walter Reisch's house, Ernst yelled out, "Valter, Valter, there's a light on in the second floor." Reisch responded by yelling out "Right avay, Ernst." Next door, Laurence Olivier leaned out of the window. "My God," he bellowed, "are the fucking Germans here already?"

When writing the script, Lubitsch and Raphaelson had either Fredric March or Rex Harrison in mind for Henry, but Fox was hardly a star-studded studio, and Zanuck asked him to screen test one of their few contract stars: Don Ameche.

Unfortunately for the two men, who wanted to hold out for someone bigger, the actor was so good they couldn't deny him the part. Ameche would remember the director as a genius, calling him "dedicated," but co-star Gene Tierney struggled with her scenes and was terrified by Lubitsch's tendency to scream at actors to get what he wanted ("I'm paid to shout at you," he'd tell the actress). She would remember him as a "tyrant."

Ameche had a difficult job embodying the character, who was both a proxy for the director and the embodiment of his nostalgia for "an age that has vanished, when it was possible to live for the charm of living." For Lubitsch, Henry's major transgression against the social mores of this time and his class was that he was sexually "fifteen years ahead of his time, all the time."

After his first two projects for Zanuck fell through – a Ginger Rogers vehicle called Self-Made Cinderella and an adaptation of the hit Broadway play Margin for Error, which ended up being made by Otto Preminger, who had directed it onstage – he settled on a play by another émigré from a now-vanished Europe, Laszlo Bus-Feketé.

Birthday was originally produced in 1934 as Születésnap. Bus-Feketé was a journalist and critic who had covered the 1936 Berlin Olympics before moving to Hollywood, where he'd write scripts for films like Reunion in France (1942) with Joan Crawford and John Wayne and Lydia (1941) with Joseph Cotten and Merle Oberon.

He might have been part of Lubitsch's extended Hollywood community of creative refugees from Europe. In any case Lubitsch transplanted the story to America and kept Henry's grandfather and Martha's fierce provincial parents, but softened his hero's character out of necessity: in the original play he sleeps with his wife's younger sister and marries her after he becomes a widower.

The original film begins on its protagonist's 15th birthday. Lubitsch and Raphaelson made this framing device even more relentless, and the story happens over successive birthday celebrations for Henry, from his 15th to 26th to 36th to 45th to 50th to 60th, in 1932, which is celebrated by a gathering of his living relatives that – as Henry notes in his voiceover narration – together have a total age of 1400 years.

The passing of time is measured but relentless, and characters drop away at intervals. His beloved grandfather survives long enough to be his accomplice when he has to travel to Kansas to persuade Martha to come back after she's left him, stung by one too many poorly-concealed affairs. The next time we see him he's an oil portrait in the Van Cleves' library.

Eyman calls Henry Van Cleve a "gentle playboy," stating that he was "Lubitsch's ideal image of himself, and the beautiful, forgiving Martha is the mate he was never lucky enough to find."

A lot of charm is required to pull of Henry and Ameche, with his silky voice and perpetual air of self-amusement, vindicated Zanuck's confidence. The film would be released at the apex of his career at Fox, when he was Fox's second highest wage earner after studio head Spyros Skouras. He was also a radio star alongside Frances Langford in The Bickersons.

Ameche's career would take a slow but steady nosedive in the '50s that would last until the '80s, when director John Landis acted on a hunch that the actor was still alive (they found his name in the telephone directory; he had no agent at the time) to cast him with Ralph Bellamy as the villainous Duke brothers in Trading Places (1983).

This began an epic late third act comeback for Ameche, who went on to star in Cocoon (1985), Coming to America (1988), Things Change (1988) and Cocoon: The Return (1988), before replacing Spalding Gray in the hit revival of Thornton Wilder's Our Town at Lincoln Center in 1989. He would die in 1993 at the Scottsdale home of his once-estranged son Don Jr.

The elegiac tone of Heaven Can Wait was no accident – nothing was in a Lubitsch film. He would make two more films: Cluny Brown (1946) and That Lady in Ermine (1948), which would reunite him one last time with Raphaelson. But the release of his last film was posthumous, as the director's heart finally gave out in November of 1947.

One day at lunch in the executive dining room at Fox, Lubitsch made a joke after Zanuck had been arrogantly pontificating about his art collecting and the Mona Lisa. Almost no one laughed except columnist Leonard Lyons, and Lubitsch invited him to dinner. After the dinner Lubitsch accompanied Lyons on his drive home, passing the Beverly Wilshire Hotel.

"It happens to us all here," Lubitsch said sadly to Lyons. "We arrive from all over the world, carrying a small bag and check into this hotel. Then, if our movies are good, we buy paintings and move into a house. They house is too big for one person so we marry. Then comes the divorce, and we take a small bag and check into the Beverly Wilshire, buy paintings, move into a house, it's too big...around and around and around."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.