The first thing that has to be understood about The Americanization of Emily, the 1964 black comedy written by Paddy Chayefsky and directed by Arthur Hiller, is that nearly everyone involved in making it was a veteran. It certainly explains motivation – and not just Chayefsky's compulsive urge to attack establishment tropes – but also the film's failure at the box office, a blow that would sour Chayefsky on Hollywood (and vice versa) for the rest of the decade, until he made his comeback with The Hospital in 1971.

Chayefsky had been wounded in Germany, and Hiller had been a bomber navigator in the RCAF. Star James Garner was in the merchant marine during WW2, and had fought in the Korean War, while Melvyn Douglas had fought in both world wars. Julie Andrews had lived in the UK as a child during the war, though she would protest that the story that her singing voice was discovered in air raid shelters during the Blitz was a myth. James Coburn spent his time in uniform as a postwar draftee driving trucks and working as a DJ at an army radio station in Texas, before narrating training films while stationed in West Germany.

But the audiences for the film, released barely twenty years after V-J Day, would have been filled with veterans with recent memories of life in uniform, and all the peculiarities of military bureaucracy at its wartime height. They had been ready for Billy Wilder's Stalag 17 over a decade earlier, not to mention comedies like Operation Petticoat and Mister Roberts, but The Americanization of Emily went a little too far.

Critic Judith Crist wondered if "World War Two is itself fair game for laughter" in the New York Herald Tribune, while Arthur Schlesinger Jr. wrote in Show magazine that while the film contained "an abundance of delights," its anti-war message might be premature, and more suitable to the First World War. "To write this way about the Second World War invites the conclusion that it is not only unpalatable to most audiences (outside Germany) but, most important, is wrong."

The Americanization of Emily is the story of Lt. Commander Charlie Madison (Garner), a staff officer and batman for Rear Admiral William Jessup (Douglas), in London in advance of D-Day, there to represent the Navy's interests in the invasion. While crisp martial music plays over the opening credits, we watch Jessup, Charlie and his best friend "Bus" Cummings (Coburn) arrive at night on a military transport at a British airfield.

Charlie efficiently marshals the luggage and other cargo off the plane and into a parade of trucks, and the brass into a line of black cars driven by young English women in uniform, his own car driven by Emily (Andrews), whose expression silently signals her disapproval of staff officers like Charlie and the bloated train of luxuries following in their wake. Charlie is obviously good at his job, efficiently seeing to the needs of the Admiral while they bivouac at the Westchester Hotel (clearly meant to be the Dorchester in Mayfair, home to General Eisenhower and his staff, not to mention much of the British cabinet during the war).

Charlie is a charmer – a "good time Charlie" who casually slaps the behinds of other female drivers while he goes about the business of provisioning the Admiral for his stay in London, but gets rewarded with a hard slap on the face from Emily when he gets similarly familiar with her.

"You Americans are really enjoying this war, aren't you," Emily says the next day, when she's assigned to drive him again. "It's just a big Shriners convention to you Yanks." It's one of several sizzling dialogue scenes Chayefsky wrote for the picture, setting the cynical American against the disapproving Englishwoman on their way to inevitable romance.

Charlie is a "dog-robber" – an adjutant tasked with providing his commander and other brass with luxuries out of reach to British civilians living on rations, not to mention the average dogface or rating. They're embodied by four items: whiskey, stockings, Hershey Bars and American cigarettes, but can include tropical fruit and avocados that would remain unseen by a generation of Brits, not to mention racks of designer clothing and perfume that fill Charlie's room at the Westchester, which is considered a better shopping destination than any place in London's West End, if you're lucky enough to gain access.

Nobody denies this basic fact of wartime life; accessing or stealing this treasure was a major preoccupation of the black market, and Piccadilly's Rainbow Corner, home of the American Red Cross Club, was a hotspot for spivs and other black market operatives during the war. British generals dined off fine china and silverware while on campaign like Lord Cardigan at Balaclava, and the first job of the advance guard behind troops taking an enemy town was to find the best house to serve as barracks for commanders and their staff – a mansion would do, a castle was optimal.

My father served in the 168 Heavy Transport Squadron in the RCAF during the war, and besides flying mail and other essential supplies to soldiers fighting in Europe in converted American heavy bombers, they would also find space in the planes for luxuries for the general staff, like fresh turkeys at Christmas and other treats. More than any other war, the Second World War was fought by citizen soldiers – conscript armies answering the call of their state – but it was no secret that general staff still lived like princelings, to a simmering resentment that (amazingly) only rarely became a problem for morale.

Not quite twenty years after the war, it was obviously still a sore memory.

Emily resists Charlie's overtures until, at the end of one of Chayefsky's typically tart dialogues, he calls her a prig. The comment stings; she wasn't always a prig. She's already lost her father and brother to the war, and a husband whose plane was shot down not long after their wedding.

After he died, she recalls to friend and fellow driver Sheila (Liz Fraser) that she'd gone a bit mad while working as a nurse, sleeping with wounded soldiers she'd been tending before they were shipped back to the front, paying for the night in a cheap bed and breakfast herself. It nearly destroyed her, which is why she asked for a transfer to the motor pool.

Charlie's story is less tragic. Before the war he'd worked as night manager at a diplomatic hotel in Washington, DC – a job whose skillset involved being something of a procurer, for which he had a talent. Generals and Admirals had tried to lure him into uniform to work as their dog-robber, but he decided to enlist in the Marines, and went ashore at Guadalcanal, where he discovered that he was a coward, not a hero, and that he wanted to live at any cost. Once recovered from his wounds he begged Jessup to take him on, to hide in plain sight as a coward in uniform, exercising his only skill useful to the military.

Charlie's cowardice becomes attractive to Emily. "Every man I love has died in this war," she tells him, and his commitment to not dying is an appealing refuge for her broken heart. She takes up his offer to be a bridge partner for a general at one of Jessup's parties (Charlie approves of the Danish crystal and Italian lace tablecloth the hotel is able to provide for the dinner table), but unlike her friend Sheila she won't change her hair colour or outfit herself from the ladieswear department in his hotel room – a transaction that will only lead to inevitably sexual ones.

But after he sees off the guests and puts the Admiral to bed, he finds Emily waiting for him in his room, and their affair begins.

The Americanization of Emily is one of the first films to frankly acknowledge that wartime Britain, and London in particular, underwent a dry run for the sexual revolution under the cover of blackout. It was implied in the 1956 movie version of The Man Who Never Was, and openly depicted in Operation Mincemeat, the recent Netflix remake of that true story of wartime espionage.

It was the basis for jokes, noted by Mass Observation, the British government's social research project that ran for nearly three decades starting in 1937, and quantified by spikes in numbers of illegitimate births and cases of venereal disease, especially after American GIs started arriving in the UK after Pearl Harbor.

"As soon as the bombs started to fall, the city became like a paved double bed," recalled writer Quentin Crisp. "Voices whispered suggestively to you as you walked along; hands reached out if you stood still and in dimly lit trains people carried on as they had once behaved only in taxis."

In a movie with a romance and a comedic farce at its heart, it's probably the most realistic thing about the picture, which like so many films set during the war at the time, lets Andrews and the rest of the uniformed female cast sport fashionably teased '60s hair and kitten heels instead of parted curls and the standard issue oxfords worn by the women in the ATS, the WRNS and the WAAF.

(Movie costume designers would at least fix the shoes by the time they made The Battle of Britain in 1969, but it wouldn't be until the '70s that the '40s would be portrayed by Hollywood as a decade with a discrete and distinct period style. I have always wondered why audiences with adult memories of the decade allowed this to persist without apparent protest.)

Also very contemporary is the swinging playboy lifestyle and the casual sexism embodied by Coburn's Bus. Coburn treats the role like a dry run for his later Flint films, with a running joke where Garner's Charlie constantly barges into his room while he's in bed with a succession of naked or nearly naked women – dubbed the "Three Nameless Broads" in the cast list, one of whom is played by Laugh-In's Judy Carne.

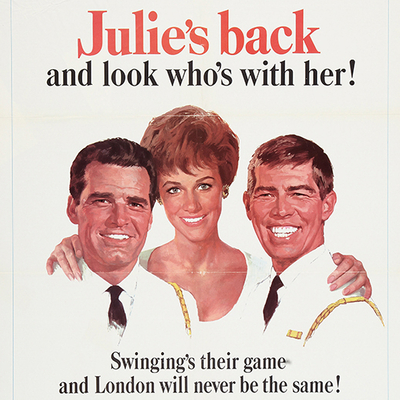

The picture is based on a book by William Bradford Huie, and produced by Marty Ransohoff, then known for Mr. Ed and The Beverly Hillbillies. He was looking for a classier project for his production deal with MGM, and for a while had William Wyler attached to direct, and William Holden set to play Charlie. Garner was signed to play Bus.

Problems began when Wyler started being difficult, delaying filming, and it became obvious that he simply didn't want to go on location. Then he started asking for changes to Chayefsky's script, which he had called brilliant two months previous.

During one of Charlie and Emily's arguments, he tells her to "lay off, Mrs. Miniver." Ransohoff would later recall that Wyler was "basically...a traditionalist. He had directed these two very sentimental war movies (Mrs. Miniver and The Best Years of Our Lives), and here was a script written by Paddy that was very iconoclastic. So Willie began to have second thoughts."

Wyler had a re-write done, which Chayefsky hated, and issued the producer an ultimatum to choose between Wyler or the writer. Ransohoff chose Chayefsky. At the same time Holden was becoming difficult; Julie Andrews, who had just filmed her movie debut in Mary Poppins, had been cast as Emily (after Julie Christie turned down the part), but Holden and his agent Charles Feldman wanted her replaced with Capucine.

Feldman then took Wyler's departure as an opportunity to invoke his client's right to choose a new director, putting forward names like Howard Hawks, Joseph Mankiewicz, David Lean, George Seaton, John Sturges and Billy Wilder. They even had meetings with Blake Edwards, an up-and-coming young director, who wanted to rewrite Chayefsky's ending.

In Mad as Hell: The Life and Work of Paddy Chayefsky, writer Shaun Considine notes another objection Edwards had to the project:

"He also wanted to recast the leading lady, whom he considered 'wrong' for the role. Julie Andrews was too wholesome and sweet to play Emily. 'She has lilacs for pubic hairs,' Edwards said, an opinion he undoubtedly rescinded a few years later when he married her."

Ransohoff preferred Arthur Hiller, a young Canadian who had just directed The Wheeler Dealers starring Garner for him at MGM. After settling with Feldman after letting Holden go, the producer announced that Hiller was the director, Garner was moving up into the part of Charlie, and after a brief discussion of using Lee Marvin, Coburn was cast as Bus, who would play a crucial role in the major deviation Chayefsky took from Huie's book.

While Charlie and Emily's romance is beginning, the Admiral is starting to lose his mind. He's in London to oversee the Navy's part in Operation Overlord before heading back to Washington to testify in a hearing that he knows will be a prelude to the drawing down of the peacetime Navy, to the Army and the new Air Force's benefit. This is a wholly accurate plot point, and part of a perpetual interservice rivalry that continues to this day.

He's inspired to orchestrate a public relations coup for the Navy, and plans to send a camera crew in with the first wave of Navy demolition divers tasked with blowing holes in Nazi shore defenses. The Admiral has been having episodes since his wife had died the previous year, and becomes obsessed with creating a Tomb of the Unknown Sailor, the first Allied casualty of D-Day.

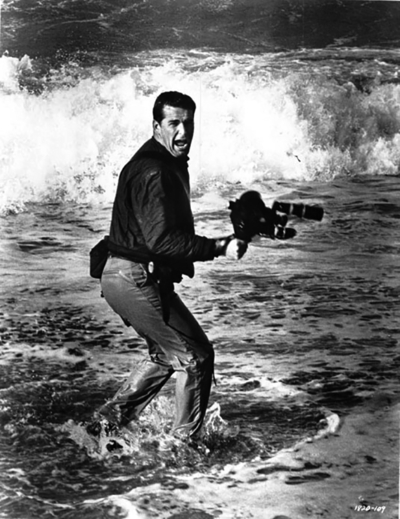

Despite his very vocal objections to the suicidal plan – and the lack of personnel to carry it out on short notice – Charlie gets tasked with leading the film crew onto Omaha Beach. At first Bus connives to help him, sending Charlie and Emily on fake assignments to Surrey and Cornwall to waste time before the invasion starts, but Bus, an Annapolis man, gradually comes around to the insane plot, assigns himself to the crew, and cuts orders for the two of them to join the flotilla when it sails, with Charlie operating the camera.

There's a great deal of argument between Charlie and Emily about motivation, duty, cowardice and sacrifice leading up to the eve of the invasion, and it culminates in them bickering in the rain at the airport. Charlie thinks he's outsmarted Bus by having them arrive too late to get on a boat, but when the invasion is postponed by a day – as it was in real life – there's no escape.

Eisenhower's famous address to the invasion troops ("You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months...") is heckled while being read in the landing ships, while soldiers vomit into their helmets. A brutal moment where the Higgins Boat Charlie and Bus are in is blown up by a direct hit is immediately followed by the two men being comically thrown in the air, like a cartoon.

Charlie balks as soon as he's on the beach and tries to run back across the English Channel, but Bus shoots him in the leg and chases him back into France. A quarter million dollars of the movie's budget was spent on the D-Day sequence, which ends with Charlie blown up again by a shell, apparently dead. (Garner broke two ribs during filming when he fell on his canteen.) Back in London the Admiral has come to his senses, sick with guilt over sending Charlie to his death, but intends to push ahead with making him the Navy's useful martyr until they learn that he's still alive, and back in Southampton with the evacuated casualties.

None of this complicated business was in Huie's original book, which had a much more straightforward, happy ending. "Naturally this leisurely premise was too tame for Chayefsky," writes Considine in his book. He had a better idea, more suited to his iconoclastic worldview.

"Eisenhower, according to the Admiral, was a man who spoke in platitudes, 'thinks in platitudes,' and almost lost the battle in North Africa," Considine wrote. Chayefsky conceived of Huie's story as a scathing satire of the military mindset. He rewrote Charlie – called James in the novel – as less upper class, and changed him from a pacifist novelist to a hotel night manager. He knew that audiences wouldn't "buy a pimp and a pacifist in the same basket" so he made him a proud coward.

He also changed Emily from Huie's "English virgin" with a scant handful of sexual experiences to the quietly troubled woman Andrews played. The major conflict isn't just Emily's refusal to be "Americanized," but Charlie's unwillingness to glorify war and its sacrifices, especially at the cost of his own life, and her aversion to him imagining his cowardice as a virtue.

The film is full of great performances, from Douglas to Keenan Wynn's small role as a grizzled, drunken old sailor assigned to Bus and Charlie's crew, and Coburn brings his uniquely manic energy to Bus. But it's Garner who really shines; his unique persona – the amiable, occasionally comic, reasonably cynical anti-hero – was formed on TV with Maverick, and he'd played Hendley, the "scrounger" in The Great Escape.

He'd do further variations on the character in Grand Prix (1966), as Wyatt Earp in Hour of the Gun (1966) and as detective Philip Marlowe in Marlowe (1969), one of the first neo-noir re-imaginings of the character. And he'd refine it to its essence with six seasons as Jim Rockford on The Rockford Files.

Andrews was desperate to get the role, knowing that Mary Poppins would get her typecast, and she begged her agents to "let me do something whacky or mad or sexy or whatever." But when it came time to promote the film the actress hung back, reportedly saying that she thought she was "a little lost in the part."

Hiller, who would work with Chayefsky again on The Hospital, said it was his favorite film, as did Garner and Coburn, and eventually Andrews would agree. The film opened to great reviews ("It is a fiercely funny picture," wrote Bosley Crowther in the New York Times. "And what it says is tart and profound.") but it flopped at the box office, and most people blamed the anti-war message. James Coburn blamed it on timing.

"President Kennedy was dead," he said later. (They were filming the film's party scene when the news from Dallas was announced). "Lyndon Baines Johnson was in the White House. The war in Vietnam was escalating. And here we were talking about shutting things down, saying let's not get involved in any more wars."

"I don't know, it's strange, but there is a great deal of pressure that the politicians put on film companies before they release pictures – pressures that a lot of people don't like to advertise. Probably some of that happened with this."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.