It's 2005. Amid the global instability in the years following 9/11, an unlikely man glides in and out of the most powerful circles on earth. He's trying to save a troubled world. To that end, he meets with presidents and prime ministers, popes and priests, royals and senators, industrialists and technologists, billionaires and media magnates. He cajoles, invites, suggests, appeals, quotes the Bible, challenges, distributes, befriends, prays, mediates, and eventually, directs—successfully. He initiates, or plays a major role in, dozens of major global events. Finally, New York Times Magazine decides to do an extended investigative piece on the man. They assign James Traub, a journalist specializing in politics and economics.

Entitled "The Statesman", Traub's nearly 10,000 word piece concludes that U2 singer Bono is "the most politically effective figure in the recent history of popular culture". He is no less than a "one-man state". The state treasury he embodies, so to speak, teems with "the global currency of fame"—and more. He is an unprecedented, and apparently irresistible, force.

What exactly has the singer done to merit such a description? Lots. Here are just three examples.

By the time 1983's "New Year's Day" catapults U2 into the musical big leagues, violence in Northern Ireland is endemic. The IRA bombs, kidnaps, kills. The UVF does the same. Not even the republic is immune. People choose sides. Everyone is affected. And there is no end in sight.

For the next fifteen years, Bono and the band use all their fame, all their cultural currency and moral authority, to promote a non-violent resolution to The Troubles.

They mention it in interviews. But they also sing it—they write it right into their songs. They symbolize their pacifism with a white flag—white like the dove John mentions in describing the spirit of God descending upon Jesus, and which everyone in religious Ireland has heard of. They fly the flag at their shows. People—young people especially—buy into the message. Conveyed by the music, the oft-repeated message seeps into the population, and spreads, deeper and deeper, wider and wider.

Finally, in the late '90s, the warring parties start peace talks. They propose an agreement for public ratification. But certain factions hold out. The yes campaign begins to falter.

At that crucial moment, during a concert in Belfast, Bono asks Ireland to vote yes. And then, he invites long-time political rivals John Hume, nationalist leader, and David Trimble, unionist leader, on to the stage. They walk out. He invites them to shake hands. They do. The crowd can hardly believe what they're seeing, and begin to cheer. But so do hundreds of thousands around the country the next day, as they see the photograph they will never forget. Maybe this can actually happen. Maybe this agreement, for all its flaws, is really our only chance.

One observer later writes:

It was an astonishing moment—another signal that the seemingly hopeless mould of Northern Ireland politics had fractured. John Hume, bless his enormous heart, left the stage in tears. [...] Bono hymned the joys of collective action, of rolling on in spite of the differences.

David Trimble constantly referred to the show during the rest of the campaign. He talked about his 14-year-old daughter, and his expectations for her life, and the guy was visibly softening up. It was a tangible issue. It mattered.

A Belfast city councillor later reports that the event "added six to seven per cent to the turnout – and that made the difference between unionism saying Yes and No." The Irish broadcaster Stuart Baillie says about the event, "Rock and roll saved Northern Ireland".

Inaccurate? Maybe. But maybe not. Maybe those commentators are right. I'm not sure the Good Friday Agreement happens, at least at that time, without U2's fifteen years of prior influence on Irish public opinion (particularly on the younger generation), or their efforts to get it across the finish line. After all, even simple photographs can significantly shift public opinion. Maybe the biggest band in the world, on their own island, actually did the same.

Another example: In the late '90s, Bono gets behind the idea to cancel Third World debt. He manages to win over key player after key player—evangelist Pat Robertson, liberal activist Bobby Shriver, Republican senator Jesse Helms, Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, David Rockefeller, economist Paul Volcker, Republican senator John Kasich, Democratic Representative Maxine Waters, World Bank President James Wolfensohn, and dozens more. In the end, thanks in no small part to Bono's "persuasive charm", debtor countries forgive around $100 billion dollars of Third World debt.

Then there is the case of Bono's influence on the George W. Bush Administration. Concerned about the AIDS epidemic ravaging Africa, Bono, in early 2002, sets about to convince the American federal government to donate billions for AIDS prevention and treatment.

To achieve his goal, Bono begins visiting with members of the administration—most notably, Secretary of State Condi Rice, and Secretary of the Treasury Paul O'Neill. He also visits with members of Congress, including the North Carolina senator Jesse Helms, then the powerful chair of the Foreign Relations Committee, and a longtime foe of foreign aid.

Helms is skeptical. But in a private meeting, Bono reads passages from the Bible, sharing his view that AIDS is to the modern era, what leprosy was to Christ's era. This analogy resonates with Helms. And then, he begins to cry. "Son, I want to bless you. Let me put my hands on your head", says the 81 year old senator.

Helms then pronounces blessings on Bono's head. Shortly thereafter, Helms writes an op-ed for the Washington Post announcing he has changed his position on sending aid to Africa. He confesses to feeling shame for not having done more to stop the AIDS epidemic. Helms even acknowledges his new position is inconsistent with his strict constitutionalism (which requires very limited government), but then justifies the inconsistency by saying "not all laws are of this earth. We also have a higher calling, and in the end our conscience is answerable to God...I know that, like the Samaritan traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho, we cannot turn away when we see our fellow man in need." Hell has frozen over.

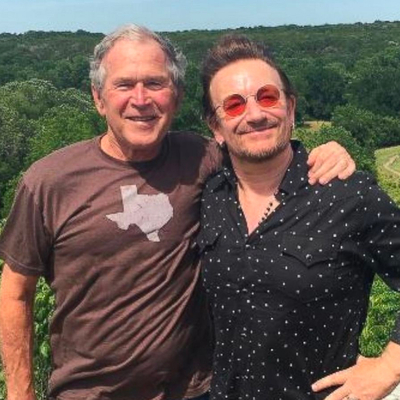

Bono finally wins over George W. Bush himself (with Jesse Helms's help).

As a direct result of Bono's political maneuvers, the Bush Administration, with Congress's approval, ends up committing $15 billion dollars to help prevent and treat AIDS in Africa and the Caribbean. Obama later continues that aid program, sending over billions more. According to Bono, the aid money saves tens of millions of lives.

These are just three examples of spectacular, macro-level political efficacy. I could have listed many more. I'm not here commenting on the pros and cons of the policies, so save the hate mail. I'm marveling at the amount of political power Bono and U2 attained, and used.

Backing up a bit, that rocket-rise to power began during a four year period following the success of "New Year's Day" in 1983. The band produced hit after hit—"Sunday Bloody Sunday", "Pride (In the Name of Love)", "With or Without You", "Where the Streets Have No Name", "I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For"—and by the last week of April, 1987, U2 got their first #1 album in America, The Joshua Tree. That very week, I saw U2 perform at San Francisco's Cow Palace in front of about 14,000 people. Only seven months later, during the same tour, I saw them again. This time, they had sold out the 50,000 plus seat BC Place Stadium, and were selling out stadiums every night. They had become the biggest band in the world. (You can see a portion of the exact BC Place Stadium show I saw here).

But U2 hadn't become only the biggest band in the world. They'd become the most important, at least in the minds of their growing legions of fans, and of almost all the cultural overlords of the time.

Why important? Because, as I mentioned in a previous installment, U2 from the get-go cast themselves as much more than a band. They were a moral crusade dedicated to changing the world for the better. Here, for example, you can watch a 23 year old Bono say as much, in an early TV interview.

U2 made good on their mission statement by throwing in with almost every social justice movement of the 1980's: anti-apartheid, human rights, political prisoners, etc. Along the way, their daring, near-trainwreck 1985 Live-Aid performance went down as one of the event's two major highlights (the other being Queen's performance), and massively boosted their international profile. It also helped blast into public consciousness the idea that music, the arts, entertainment, had a new, vital role to play in the world. And it helped establish U2 as a moral force and authority.

As I mentioned, the cultural overlords loved this new turn in music. One prominent example was Jann Wenner, the founder and longtime editor of Rolling Stone magazine, and head of a media empire.

At the time U2 broke, Wenner was a kingmaker—not just in music, but in book publishing, television, fashion, film, art, and more. U2's Christian idealism resonated deeply within him. In 1985, Wenner gave U2 the Rolling Stone supreme stamp of cultural importance and legitimacy by putting them on the cover (he would put them on the cover many more times in subsequent years). He also authoritatively pronounced them "Band of the 80's", even though the decade was only half over.

Like many of his counterparts, Wenner (as he made clear in several interviews) saw in U2 the resurrection and (literal and metaphorical) amplification of the world-changing liberal idealism of his youth. That U2 continued to invoke the name of Jesus didn't matter to the non-religious, ethnically Jewish Wenner. It was the realization of liberal idealism which did. For Wenner and his fellow culture merchants, in U2, because of U2, music could become—was becoming—global humanitarian religion. The songs were the hymns and the advertisements. But the redemptive theology—the action-oriented mission—driving the songs was the real point. It could revolutionize the world. And it was already penetrating other forms of art and entertainment. Wenner needed to be part of it. Everyone did, in his mind. What was the point of mere entertainment? Of pop culture? Ideally, entertainment would do more than entertain—it would also mean something. It would advance progress, heal, feed, inspire, save. This is what U2 represented for Wenner. Art and entertainment needed—and now had—some kind of higher purpose. By extension, Wenner and the Culture Class now did, too.

Wenner wasn't alone in recognizing the cultural importance of the new mission-driven band. The Washington Post, The New Yorker, Newsweek, the Archbishop of Canterbury, academics, and a hundred other influential voices exulted in the quasi-religious movement that was U2. Listen to Time magazine in 1987:

U2 seem to be citizens of some alternative time frame spliced from the idealism of the '60s and the musical free-for-all of the late '70s...Their concerts are as revivifying as anything in rock...U2's songs speak equally to the Selma of two decades ago and the Nicaragua of tomorrow. They are about spiritual search, and conscience and commitment, and it follows that some of the band's most memorable performances have been in the service of a good cause, at Live Aid or during last summer's tour for Amnesty International. This is a band that believes rock music has moral imperatives and social responsibilities.

I'm once again over limit, so I'll just finish up this piece (and mini-series) with two quick thoughts (which I lack space to properly defend, but here goes anyway).

Social justice messaging, in almost every facet of arts and entertainment, is now nearly ubiquitous. Where, when, how, did that begin? You can't find much of that on '70s or early '80s sitcoms, movies, or bands. Back then, if you wanted a sermon, you went to church. You didn't buy a movie ticket or a record album.

Now, of course, the world is different. I'm suggesting it's not a coincidence that the rise of social justice messaging followed the rise of U2, a band which pioneered, normalized, made hip, far more than any other act before it, the use of art and entertainment as a means of moral crusade (and the use of fame as a tool for gaining political power). I'm not saying U2 is solely responsible for starting the social justice messaging trend. But I suggest they were an important—maybe the most important—cause of it.

Some of my readers may feel ambivalent about Bono's particular political causes and worldview. I know the feeling. I didn't have space to dive into what appears to be Bono's anti-nationalism; his seemingly uncritical endorsement of whatever Establishment "opinion-mandate" happens to pop up on any given day (Ukraine/Zelensky, mRNA injections, etc.); a pro-choice position which seems to conflict with Christian doctrine; or the fact he didn't notice any contradiction between what he calls his "militant pacifism", and his 2016 support for the rancorous, corrupt, warmonger, Hillary Clinton. Or a dozen other things.

But we don't need to agree with all, or even any, of Bono's political causes to learn a few lessons in the art of power from him, or marvel at his efficacy. Or marvel at how U2 changed the whole thought-world of art, entertainment, culture, and politics. Those are my first thoughts as I think back on the breakthrough of "New Year's Day" forty years ago, and ponder the extraordinary influence U2 has had on the world ever since.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Tal know what they think in the comments below. Commenting is one of many perks that come along with Club membership, which you can check out for yourself here. Tal will be among Mark's special guests on the upcoming Mark Steyn Cruise along the Adriatic, which sails July 7-14, 2023. Get all the details and book your stateroom here.