When The Solid Gold Cadillac came out in 1956 the top five companies on the Fortune 500 list were, in descending order, General Motors, Exxon Mobil (then known as Jersey Standard or Standard Oil or Esso), Ford Motor, U.S. Steel and Chrysler. I doubt if this is a surprise to anyone then or now, though it was only the second year that Fortune had compiled the list, which would become a benchmark of global capitalism for decades afterward, not to mention a wildly successful branding exercise for the magazine.

Browsing the top 100 is an exercise in nostalgia. Some major players remain today (AT&T, Boeing, Monsanto). Several have merged (DuPont and Dow, General Foods and Kraft, Douglas Aircraft and Boeing, Jersey Standard and Mobil). But many once iconic companies have either fallen into irrelevance (Eastman Kodak, Singer, RCA) or disappeared altogether (Studebaker, American Motors, Bethlehem Steel) – victims of tectonic shifts in business, economics, technology and consumer taste.

At the start of The Solid Gold Cadillac, narrator George Burns informs us that Americans are bullish on the stock market, with a whole class of small stockholders becoming "the backbone of American industry." In his book An Extraordinary Time: The End of the Postwar Boom and the Return of the Ordinary Economy, Marc Levinson writes how after WW2, "people who had thought they were condemned to be sharecroppers in the Alabama Cotton Belt or day laborers in the boot heel of Italy found opportunities they could never have imagined."

For nearly two decades the postwar economic miracle "brought healthy profits for businesses...As profits grew, so did employees' wages, shareholders' dividends, business tax receipts and investments in new capacity to produce yet more goods and services." Levinson calls this a "virtuous circle that put the glow on the Golden Age."

The film begins at a shareholder meeting for International Projects, a publicly traded, billion-dollar corporation that makes everything from pins to clocks to fridges to automobiles to locomotives. While the name of the fictitious company is meant to evoke an enigmatic conglomerate like Continental Group (#47 on the Fortune 500 in 1956), ITT (#80) or International Business Machines (#59), the movie imagines it as a vertically diversified manufacturing entity, more like a Japanese keiretsu or a Korean chaebol.

The main order of business at this meeting is to celebrate the replacement of the outgoing chairman of the board and founder of the company, Edward L. McKeever (Paul Douglas) with John T. Blessington (John Williams), an arrogant blue blood with a plummy British accent. McKeever – a workaholic who ignores the meeting as he goes over stacks of paperwork with a secretary and an assistant (the stalwart Richard Deacon, playing yet another company man) – is leaving the company for a dollar-a-year job in Washington, overseeing defense contracts at the request of the President.

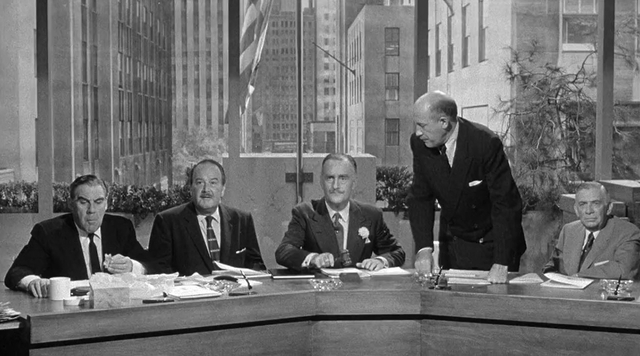

We're also introduced to the senior directors on the board – Metcalfe, Gillie and company treasurer Snell, a trio of caricatures of late middle-aged businessmen straight out of a New Yorker cartoon. The casting here is almost too perfect. Ralph Dumke (Gillie) played Tiny, the treacherous Lt. Governor in All the King's Men; Ray Collins (Metcalfe) was Orson Welles' nemesis Jim W. Gettys in Citizen Kane; and Fred Clark (Snell) had made a career out of sneering, dyspeptic blowhards in everything from Sunset Boulevard and How to Marry a Millionaire to The Beverly Hillbillies and The Addams Family.

Burns' voiceover introduces each man by telling us their job title and how little we should trust them. But it's wholly unnecessary (as is Burns' narration, to be honest) since each actor does such a good job telegraphing their unctuous, venal, greedy characters in little more than a few shifty, sidelong glances.

The fly in this self-satisfied corporate ointment is Laura Partridge (Judy Holliday), a small stockholder who has arrived at the meeting with a few questions, like why Blessington and the rest of the board are paying themselves such astronomical salaries for what seems like so little work.

Laura, a struggling actress working part-time in the menswear department at Bloomingdales, inherited ten shares of International Projects along with a cat, from a neighbour she took care of when he was ill. She's decided to take her role as a shareholder seriously, announcing her intention to continue attending meetings, perhaps even starting a shareholders association.

While this unsettles the new management of the company, who begin cutting dividends while voting themselves pay increases, Laura ends up charming McKeever quite against his will when he offers her a drive home to her apartment in Queens on his way to the airport. Douglas plays McKeever as the conscientious plutocrat, a self-made man who has sacrificed marriage and family to his business, taking his new government job so seriously that he's divested himself of all his stock in International Projects to avoid a conflict of interest.

With McKeever out of the way, Blessington and his cronies start remaking the company in their own image, going so far as to appoint the CEO's idiotic brother-in-law Harry (Hiram Sherman) to the board, and making his mistress, a dimwit model, the new public face of International Projects in their advertising campaigns. The only obstacle is Laura, whose appearances at shareholder meetings might draw undue attention to their discreet looting of the company.

Laura is what we would now know as an "activist shareholder." In a 2021 article on the Ernst & Young website titled "What boards need to know about shareholder activism," their threat is spelled out:

"In recent years, activists have even targeted companies delivering impressive shareholder returns or companies that have only recently become public. . .The stakes can also be high for individual directors. An activist's ultimate weapon is a proxy contest where they nominate one or more handpicked candidates to replace at least some incumbent directors. In the process, not only are the company and its management team targeted, but individual directors as well."

Shareholder activism has evolved into powerful hedge funds like Elliott Investment Management and Third Point, and investment firms with environmental and social justice agendas like Cambridge Associates and Invesco, which has funds focused on solar power and water industries. But in 1956 shareholder activism was imagined in the form of Laura Partridge, a naïve and unsophisticated busybody with abundant energy and curiosity – the sort of role Judy Holliday was born to play.

Holliday was at the peak of her career with the film. After her star-making appearance in Adam's Rib, she'd go on to star in Born Yesterday, The Marrying Kind, It Should Happen to You and Phffft before taking on the role of Laura Partridge. She had, by then, established her popular and indelible onscreen persona, but would only make two more films – the comedy drama Full of Life and the musical Bells Are Ringing. Holliday began a battle with cancer between production on these films and would succumb to it in 1965.

The Solid Gold Cadillac began as a hit Broadway play written by Abe Burrows (Guys & Dolls, Breakfast at Tiffany's), Howard Teichmann and George S. Kaufman. The original Laura Partridge was played by Josephine Hull (winner of a supporting actress Oscar for Harvey), who was in her seventies at the time. Replacing her with Holliday changed the role completely, and New York Times movie critic Bosley Crowther approved, writing that Holliday's "youthful figure and personality" helped to "knock the role completely dead."

The director, Richard Quine, is one of those Hollywood journeymen who worked as a writer, director and producer after beginning his career as a child actor, with his film debut in Noel Coward's Cavalcade in 1933. He would act in the original stage production of My Sister Eileen, reprising his role in the first movie version in 1942, before writing and directing the musical remake in 1955.

His filmography is a great snapshot of the end of the studio era, ranging from Bell, Book and Candle to It Happened to Jane to The World of Suzie Wong to Sex and the Single Girl to Hotel. He would direct Holliday in Full of Life, return to acting in the '70s while directing TV shows like Columbo and McCloud and making his final film, The Prisoner of Zenda starring Peter Sellers, in 1979. Quine shot himself at home in Los Angeles in 1989.

Desperate to distract Laura from their self-enrichment at shareholder expense, Blessington offers her a job at International Projects as director of shareholder relations, complete with her own office and a secretary, Amelia (Neva Patterson), who Snell tasks with spying on Laura and making sure she gets nothing done.

Laura does an end run around Snell by making friends with Amelia, advising her on her clandestine romance with office manager Jenkins (Arthur O'Connell, another reliable character actor known for his roles in Picnic, Bus Stop, Anatomy of a Murder and Cimarron). Instead of waiting for small shareholders to contact her, Laura gets to work contacting them, creating a network of relationships with spinsters, retirees, trophy wives and workers all over the country.

When the directors discover that Amelia has helped Laura by giving her access to the shareholder directory they fire her, but Laura fights back by blackmailing the directors with their cover-up of dimwit Harry's bankrupting a company he thought was competing with International Projects, but which was actually a wholly owned subsidiary. She gets Amelia re-hired and expands her department and its budget till it's larger than Snell's.

In the meantime the directors are offended as McKeever has been awarding defense department contracts to their competitors. Angry at being excluded from the gravy train, they send Laura to Washington to try to convince him to send some gravy their way; she goes, but with her own agenda to convince McKeever to return and take back the company before they mismanage it out of existence.

That there was collusion in the relationship between the Pentagon and corporate America is casually implied by this bit of plot. As McKeever was a presidential appointee, moviegoers would assume that meant Dwight D. Eisenhower, the leader of the US at the apex of its postwar explosion of growth.

Eisenhower – the master of tactics, diplomacy and logistics who oversaw the Allied invasion of Europe – would also be the president who warned of a "military-industrial complex" enriching itself during his 1961 farewell address. Clearly, the people who made and watched movies in the middle of his time in office were not unfamiliar with the concept.

There is, of course, something personal happening between Laura and McKeever – a flirtation that the executive is unwilling or unable to act upon every time he's with her. Douglas – an underappreciated actor remembered for broad but expressive features on a huge head – gives a great performance, especially when called upon to act badly, reprising his boyhood recitation of "Spartacus to the Gladiators" for Laura in her office.

It had been a hit when he was a young man and a budding thespian, the sort of overwrought monologue with classical pretensions (written in 1842 for a student competition at Bowdoin College) once popular in proudly middlebrow America. Douglas does a great job at bad acting, eliciting the same sympathy from the audience that he gets from Laura.

(There's a great moment when McKeever notices that Laura has a framed picture of him on the cover of Newsweek on her desk. He's flattered and bashful at the same time, saying that he looks like "an ex-grease monkey who got lucky." She says that he looks like an actor. "This could be – William Holden," she insists, a sly callback to Holliday's co-star in Born Yesterday.)

"You're scared of girls," she tells him frankly, and since it's meant as something of a dare, he can't help but fall for her and her scheme to take back International Projects. The only problem is that he's not only the ex-CEO, but he no longer owns any shares.

There's something lovely about the romances in The Solid Gold Cadillac, none of which are between people we'd consider leading men or ingenues. Holliday was an unlikely leading lady, to be sure, but actors like Douglas rarely played the romantic lead. And then there's the secondary couple, Amelia and Jenkins, who have to sublimate their passion while waiting for their circumstances – his family, her uncertain wages – to allow them the luxury of marriage in middle age.

At the climax it's Laura and McKeever, aided by Amelia and Jenkins, against the directors of the board, and it's Laura and her network of small investors who (needless to say) triumph, pledging their plurality of proxy votes to her in what, to modern eyes, looks like a hostile takeover of International Projects.

It's a fantasy about corporate American run as a kind of family, with both couples sitting on the board at the shareholders meeting at the end. It looks absurd today; even Crowther at the Times said that the villainous board members were "not precisely representatives of the workaday financial world." But when employment was high enough to banish (or at least sublimate) grim memories of the Depression and the great American capitalist project was going so well, it must have been easier to look on the system charitably.

In his book The Age of Abundance: How Prosperity Transformed America's Politics and Culture, Brink Lindsey wrote how America's middle class, transformed by the world created by the war, was key to this Golden Age:

"What remained intact was the capacity for trusting and working with people outside one's intimate circle of family and friends – in other words, for forming and maintaining relationships on the basis of shared, abstract values and purposes. But the values and purposes that were shared had changed dramatically. The Protestant bourgeoisie had founded its economic dynamism on a common adherence to a particular and rigid set of religious beliefs and moral strictures. That old-time religion, with its galvanizing sense of absolute certainty and unabashed bigotry against other races and faiths, could not maintain its hold on the nation's socioeconomic elite. What emerged in its place was a creed that was both more amorphous and more inclusive."

How this intersected with a comedy happening more in the boardroom than the bedroom is up to interpretation. I will point out the scene where Laura rallies a dispirited McKeever by telling him:

"What's money got to do with it? Oh, not that I'm against it. A man needs more than money. A man needs a job to go to, a job he loves. And he needs a home to come home to, a happy home. But if he has no job to go to, how can he come home to a happy home if he's been sitting home all day to begin with?"

Which sounds, to me at least, like the Protestant work ethic adapted to the age of The Organization Man and The Lonely Crowd, if nothing else.

At the end, the shareholders show their appreciation for Laura with the gift that was in the story's title – a solid gold Cadillac, and Quine has the film switch from black and white to Technicolor just for the final shot, to showcase the final payoff.

Never mind that a solid gold car would be unfeasibly heavy, or that gold, a very malleable metal, would be the worst possible material for an engine block. After the chaos and uncertainty of the Depression and two World Wars, fresh in the minds of most moviegoers alive in 1956, America still must have felt like a solid gold Cadillac, improbable and wonderful and the kind of thing only a fool would turn down.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.