Today, it might not sound all that remarkable. At the time of its release—four decades ago this past week—it was revolutionary. It sounded like nothing else at the time, and nothing else before it.

And my claim is that U2's breakthrough song, "New Year's Day", initiated a sequence of profound changes in the whole thought-world (or maybe better, the whole spirit-world) of the West.

I realize that sounds hyperbolic, or even insane. I also realize I might be the only one on earth who would make this argument. But though my burden is high, give me a chance to convince you. I figure it'll take this piece, plus maybe one more.

You'll remember last time we discussed the state of popular music heading into the early 1980s. Disco and punk, for the most part, had cleared out the big '70s rock acts. What remained, with just a few admirable exceptions, was a mix of glossy, anodyne, mainstream Top 40 hits (the kind that never go away); (often synthesizer-heavy) post-punk/New Wave music; and a nascent wave of overblown, androgynous, fake-drama Hair Metal.

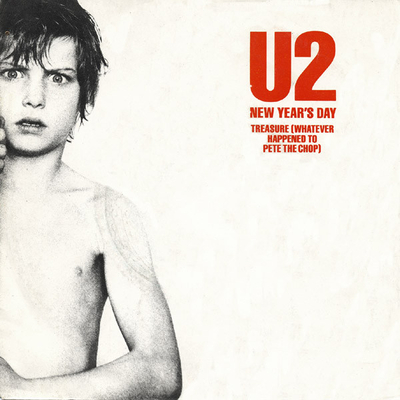

U2 had been around for a few years before their 1983 release of "New Year's Day". Their 1980 debut album, "Boy", had spawned the single, "I Will Follow". It didn't make the Billboard Hot 100, but it did do well enough on independent college radio to give them a toehold in that niche market.

This pattern repeated the next year. The band's sophomore album, 1981's "October", spawned a fine single ("Gloria"), which also failed to chart. But it got enough college radio play to maintain the band's toehold in the music scene. It was time for something big.

That something big turned out to be a distillation, or perhaps maturation, of the young band's unusual musical identity. And unusual, it definitely was.

For starters, there was the Christianity. The four lads—barely into their teens—who founded U2 in Dublin in 1976, were all believing Christians. Three of them—Paul the singer (who would adopt the stage name Bono), Dave the guitarist (who would adopt the stage name The Edge), and Larry the drummer—were particularly devout. For a while, the three even followed a Dublin-based charismatic evangelical movement called Shalom, dedicated to living a primitivist Christian lifestyle (as described in passages like chapters two and four of Acts).

In other words, in the midst of a punk/post-punk movement treading in anarchic nihilism and depression, a disco movement promoting good-time hedonism, and a waning 70s rock movement given over to antinomian vainglory and flirtations with the occult, Christianity had no place. Yet the devout young band from Dublin wrote Christian songs anyway.

Consider the lyrics to the second album's single, "Gloria", mentioned above (you can see the video here). It's a hymn of praise. Bono, the lyricist, even lapses into Latin in the chorus:

I try to sing this song

I try to stand up

But I can't find my feet

I try to speak up

But only in you I'm completeI try to get in

But I can't find the door

The door is open

You're standing there

You let me inGloria in te domine

Gloria, exultate!

Gloria, gloria

Oh Lord, loosen my lips

Oh Lord, if I had anything, anything at all

I give it to you

Gloria miserere

Gloria in te domine

(You can watch the young band in action singing this hymn live to thousands of eager young fans here).

The lyrics to the early U2 song, "With a Shout", also merit a mention:

Where do we go from here?

To the side of a hill

Blood was spilt

We're going back there

Jerusalem, Jerusalem!I want to go to The One

To the side of The One

To the feet of He who made me see

To the side of a hill

We were filled with a love

We're going to be loved

Jerusalem, Jerusalem!

Even if you loathe U2's music, you gotta give them credit: their mere existence in the early 1980s was, itself, a daring revolutionary act. In an echo of Philippians 4:3, U2—in the name of Jesus—defied the world to stop them and their message. They had perfect faith the world would fail. Turns out, it did.

Early U2's message was that true life was to be found in devotion to the divine—nowhere else. The godless world was a dead world. Only God could breathe the breath of life into anything. And he would breathe the breath of renewed spiritual life into everyone, every moment, if we accepted him, and rejoiced in him. "I can't change the world", sang Bono in a song called "Rejoice". "But I can change the world in me, if I rejoice".

All things considered, it's amazing U2 ever managed to get anywhere. Even forty years ago, college radio stations weren't exactly devotionally-inclined. They were havens of alternative/underground music, precisely none of which was religious. But college radio played those early U2 songs anyway. And for my money, it was because the music itself grabbed you. Even if you weren't a Christian, you kind of had to listen.

It was raw, for one thing: guitar, bass, drums, vocals, and the odd piano. No synthesizers or drum machines appeared. There were very few overdubs. Early U2 music sounded distinctly human (just as 70's rock music had). Bono's occasionally out-of-tune vocal notes helped convey that humanness. So did accidentally fluctuating song tempos. There were also very few overdubs and the odd misplaced guitar note. All in all, it just sounded like what it was: four young guys playing their hearts out about things they really believed in. It was passion over precision.

But offsetting the fundamental economy of U2's early music was its "big drama" spirit. Much of that came from Bono. His themes and lyrics were about deep topics: faith, loss, longing, innocence, transformation, etc. As a frontman, he radiated huge presence. And his singing ranged from pensive to explosively exuberant. What he sometimes lacked in pitch on those early recordings, he made up for with conviction, sincerity, and boldness. For anyone interested in earnest music, Bono's impassioned voice couldn't help but resonate.

Another source of "big drama" was The Edge's guitar playing. The truth is, he invented a new way of playing electric guitar. He didn't play proper chords, for one thing. Nor did he use standard techniques like string-bending or vibrato while soloing.

Instead, he developed guitar accompaniments based in double and triple stops (often using one or more drone strings); long countermelody lines; harmonics; and muted, percussive pick scrapes as a sound effect. All of these he invariably fed through effects pedals (echo and reverb pedals, above all). After a decade of dextrous, virtuoso guitar heroes like Page, Clapton, Blackmore (and eventually Angus Young, Edward Van Halen, and the LA guitar shredders), The Edge appeared as a brand new kind of guitar hero: one who exhibited no interest whatsoever in any guitar skill anyone had ever exhibited before. He was the anti-guitar-hero guitar hero. And he sounded like no one else (until, that is, thousands of new guitarists began copying him, even including rock guitar heroes like Rush's Alex Lifeson and Pink Floyd's Dave Gilmour).

Point is, on their first two albums, U2 offered up something new, compelling, and revolutionary. The problem was, relatively few people heard those two albums. And that brings us back to January 10th, 1983 (four decades ago plus a few days), when the lead off single of their third album first appeared.

"New Year's Day" was the first U2 song most people ever heard (listen to it here). It sounded like nothing else on rock radio. Recorded in an odd key for rock (G# sharp minor), the song begins with an arpeggiated piano part (played by The Edge). As you slide into the song, Bono offers up his own rebel yell. The drums kick in, and you're listening to something immediately arresting. The Edge introduces an overdubbed muted, plucked, echoing electric guitar part (at :22), which recurs throughout the song. You know right away it's something earnest and urgent. Different. Important. Maybe even apocalyptic.

The main hook isn't a chorus proper, but a few repeating lines ending with "nothing changes on new years's day" at the end of the verse lines. The recurring bridge breaks up the minor key drama by taking the song major for a few moments. And once you're in about three minutes, the introductory piano motif (a hook in itself) returns. You wonder where the song will go next.

And where it goes next is into a guitar solo. But it's not a normal guitar solo. There is no debt owed to blues or rock guitar playing at all: no standard licks, no bending, nothing like that. The only thing it owes a musical debt to is the Westminster Chimes: the melody clock bells play. The Edge's soaring, echo-drenched solo does what every great solo does, however. It surprises and delights the listener while still conforming to the spirit of the song; ratchets up the song's intensity; and takes the piece somewhere new. It's a ten out of ten.

The lyrics don't express a precise thought or story. They're ambiguous enough to get you wondering what they're about. They seem to be about a man pining for a distant loved one. But they also include enough concrete images and phrases to conjure up vivid images ("under a blood red sky, a crowd is gathered in black and white") and even indignation at human greed ("this is the golden age—gold is the reason for the wars we wage"). In all, the lyrics amount to a viscerally evocative, but not entirely intelligible, lamentation about unbridgeable separation in a high stakes time. (Bono would later cite Lech Walesa's Solidarity Movement in Poland as a partial inspiration).

"New Year's Day" drove U2 directly into the big leagues. No, it didn't instantly make them the biggest band in the world. That level of popularity would come later. But it did put them squarely into the bigs, commercially and artistically. "New Year's Day" went to the Top Ten in the UK, and charted high elsewhere in Europe. In America, it entered the Billboard Hot 100 chart, rising to #53. Perhaps more important than its Billboard charting was that the video became a huge hit on MTV, winning the band hundreds of thousands of new young fans (you can watch the video, set to an abbreviated song edit, here). Those fans would form the backbone of U2's North American fan base for at least the next decade. The success of "New Year's Day" was the breakthrough foundation for all that would come.

In the months and years that followed, U2 would use their new status to change not just the music industry, not just the broader culture industry, but the world it had started out preaching Christian detachment from. How exactly that happened, and to what extent the changes were good, are big questions. More on that next time.

~Mark Steyn Club members can let Tal know what they think in the comments below. Commenting is one of many perks that come along with Club membership, which you can check out for yourself here. Tal will be among Mark's special guests on the upcoming Mark Steyn Cruise along the Adriatic, which sails July 7-14, 2023. Get all the details and book your stateroom here.