If you enjoy Steyn's Song of the Week at SteynOnline, please note that there'll be a live stage edition during the 2023 Mark Steyn Cruise - along with many other favorite features from SteynOnline and The Mark Steyn Show. More details here.

If you enjoy Steyn's Song of the Week at SteynOnline, please note that there'll be a live stage edition during the 2023 Mark Steyn Cruise - along with many other favorite features from SteynOnline and The Mark Steyn Show. More details here.

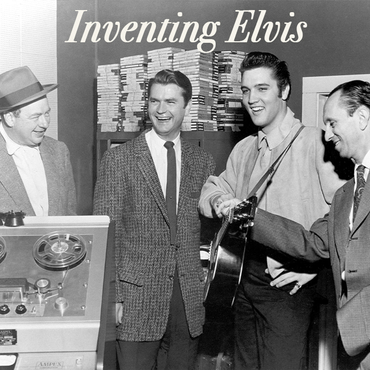

~Sam Phillips was born one hundred years ago - January 5th 1923, in Florence, Alabama. If you don't know his name, you've certainly been exposed to his legacy - whether you a) are a rock'n'roll fan; or b) stayed in a Holiday Inn last night. This essay is from Mark Steyn's Passing Parade - but, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member and you'd prefer it in audio-book version, you can find that here:

On the day Sam Phillips died, the crowd at the world's (alleged) all-time biggest rock concert, in Toronto, booed and threw bottles at teen heartthrob Justin Timberlake, of the boy band 'N Sync. Master Timberlake was said to be too "plastic" and "manufactured" for the taste of rock fans there to see Rush and AC/DC. This is the fellow to whom, as she revealed this summer, Britney Spears surrendered her much-advertised virginity, which suggests that letting the suits in the head office mold your identity is not without its compensations. But young Justin sportingly said he thought the bottle-hurling was "understandable".

And so it is. Rock'n'roll may be the most aggressively corporate branch of showbusiness ever invented but it's still obsessed with being "raw" and "authentic" and "countercultural". That's where Sam Phillips comes in: he represents rock's BC era - Before Corporate -before Elvis said goodbye to Sam's Sun Records, in Memphis, and headed for RCA and Hollywood and Vegas. But back in 1954 it was Sam who told Elvis to sing the country song ("Blue Moon Of Kentucky") kinda bluesy and the blues song ("That's All Right") kinda country, and, as Elvis was a polite 19-year old who obliged his elders, somewhere in the crisscross something clicked:

It's the Phillips tracks that redeem Elvis for everything that came afterward. It's "Mystery Train" and "That's All Right" that the pop-culture historians are thinking of when they write about the rock'n'roll "revolution". "The Ancien Régime fell in 1789 and once again a century and a half later," declared Herbert London in Closing The Circle: A Cultural History Of The Rock Revolution. "Rock Around The Clock" is the most successful call to arms produced by the revolution, the one kids tore up movie seats over. But its composer, Jimmy DeKnight, wrote it as a fox trot, and its lyricist, Max Freedman, whose last hit had been for the Andrews Sisters, originally wanted to call it "Dance Around The Clock". And Freedman was born in 1890. When he was a rebellious teenager, the big hits were "The Merry Widow Waltz", Kipling's "Road To Mandalay", and "When A Fellow's On The Level With A Girl That's On The Square". He may not have been exactly Ancien Régime, but he was certainly pretty ancien. And the regime itself - in the shape of RCA, Columbia, etc - proved far wilier survivors than Louis XVI.

That's why Phillips' moment is central to rock's sense of itself, and why critics still insist that Elvis's The Sun Sessions is the all-time greatest album. As Robert Hilburn put it, on the Sun set "you hear rock being born" - not to Tin Pan Alley hacks and big-time corporations, but in a one-story brick studio where a kid walked in off the street. Just as real revolutionaries watch the Revolution Day tank parade from the presidential palace and reminisce about the days when they were peasants with pitchforks, so fellows who spend eight months in a studio remixing a couple of tracks fondly reminisce about the days when Ike Turner's amplifier fell off the car roof on the way to the studio and Sam Phillips stuffed the punctured speaker cone with paper and accidentally created a "wall of sound". The Sun motto was "We Record Anything, Anytime, Anywhere" - including the men's room, where the toilet served as the studio's echo chamber. The conventional line on Phillips is that he's the guy who encouraged Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Roy Orbison to "experiment". "I'd try things I knew I couldn't do," Carl Perkins remembered, "and then have to work my way out of it. I'd say, 'Mr Phillips, that's terrible.' He'd say, 'That's original.'"

I interviewed Phillips once for the BBC. Well, that's not exactly true. I pretended to be from the BBC. Unfortunately, a genuine BBC chap had turned up the day before I did, which meant that, when I was ushered into his presence, Phillips seemed vaguely suspicious that I wasn't quite what I claimed to be. Desperate to reassure him that I was a legitimate rock interviewer, I somehow fell into a terrible rhythm of earnest cliché questions I couldn't get out of - about the "rawness", the "authenticity" - and, Elvised out as he was, he politely gave the standard answers for the umpteenth time. He had a laid-back cool that Elvis never quite managed, and he wore a little lightning-bolt pin with the Presley motto: "TCB." Taking Care of Business.

Here's what I would like to have discussed. He knew Elvis before he was Elvis, before he was a star and then a parody. He knew Elvis when he was an 18-year old who parked his Ford pick-up outside the studio on Union Avenue and said he wanted to record a song for his momma's birthday: "My Happiness", as recorded by Ella Fitzgerald, and the Pied Pipers, and the Ink Spots. The teenage Elvis liked the Ink Spots, and Eddie Fisher. He wanted to sing like Dean Martin - as you can hear:

Elvis's career after Phillips is regarded by rock critics as a ghastly sellout to commercialism and conformity, though there's nothing obviously commercial or conformist about a ragbag like "Old Shep", "Rock-A-Hula Baby", "Peace In The Valley", "No Room To Rhumba In A Sports Car", plus adaptations of "O Sole Mio" and "The Battle Hymn Of The Republic". Justin Timberlake's minders would be unlikely to recommend any of 'em. Elvis had an extraordinary range - two octaves and a third - but not a consistent voice. He was a chameleon but unfocused, and when he wasn't doing Dino he could sound like Al Jolson, Mahalia Jackson or an Irish tenor. The wacky eclecticism is the real Elvis. The "raw", "authentic" Sun Sessions Elvis is the manufactured product. "I encouraged him to be real raw," said Phillips, "because if he was artificial he wouldn't be able to keep it up." Au contraire: it was being raw he couldn't keep up.

Go back to that summer's day in 1953, when Phillips first heard that voice. He wanted Elvis, but he didn't want him singing "My Happiness". Nobody needed a one-man Ink Spots, or a hillbilly Eddie Fisher. "I always said," Phillips told everybody, "that if I could find a white boy who could sing like a black man I'd make a million dollars."

So he steered Mister Eclectic away from everything but one particular corner, and Elvis, as always, said, "Yes, sir." Imagine if Phillips had said, sure, kid, how about a couple more Ink Spots covers, and that "Stranger In Paradise" from Kismet's pretty nice, and you've got the pipes for it, and how about we round things out with a little Eddie Fisher. There would have been no rock'n'roll Elvis, and nothing for RCA to buy up. It would never have occurred either to them or him:

Phillips started in the Forties, recording dance bands from the roof garden of the Peabody Hotel. But that was just a job. What he really wanted to do was "race records". When he first heard Howlin' Wolf he howled, too: "This is where the soul of man never dies." To Phillips, black music was a passion. To Elvis, it was an option. And so the producer lent the singer his authenticity.

Phillips never made his million bucks, not from Elvis. RCA bought out the Sun contract for $35,000. He owned some radio stations, and he was one of' the original investors in Holiday Inn. He was a businessman, and half a century ago he made a commercial decision. Would other white boys have come along at other studios? Sure. But none ever did who sang rockabilly-country-blues like Elvis. Sam Phillips invented Elvis, and thereby mainstream rock'n'roll, and rock. Not a revolution, just a smart move. Like the tiepin says, Taking Care of Business.

~adapted from Mark Steyn's Passing Parade. As mentioned above, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member and you'd prefer it in audio-book version, you can find that here - including that Elvis version of the Ink Spots.

On the other hand, if you're old-fashioned enough to like your books in book form, personally autographed copies of Mark Steyn's Passing Parade are exclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore - and, if you're a Steyn Clubber, don't forget to enter your special code at checkout for special member pricing.

If you're one of the many Elvis impersonators among our Club members, do feel free to weigh in in the comments. For more information on The Mark Steyn Club, see here.

Steyn's Song of the Week airs thrice weekly on Serenade Radio in the UK, one or other of which broadcasts is certain to be convenient for whichever part of the world you're in:

5.30pm Sunday London (12.30pm New York)

5.30am Monday London (4.30pm Sydney)

9pm Thursday London (1pm Vancouver)

Whichever you prefer, you can listen from anywhere on the planet right here.